Over decades of bloody conflict in Northern Ireland, a near sacred mystique grew up around the intelligence services. Spoken of in reverential tones, largely unaccountable and unscrutinised, they were depicted by the media as an omniscient elite.

A description, for example, selected at random online, of a book on the “intelligence war”, turns this up: “The men and women who work in this field are a special breed who undertake hazardous risks with unflinching tenacity and professionalism”.

With publication of the interim report of “Operation Kenova” on Friday, that myth crashed to earth. It revealed a squalid, boastful yet tragic reality – more Keystone Cops than James Bond.

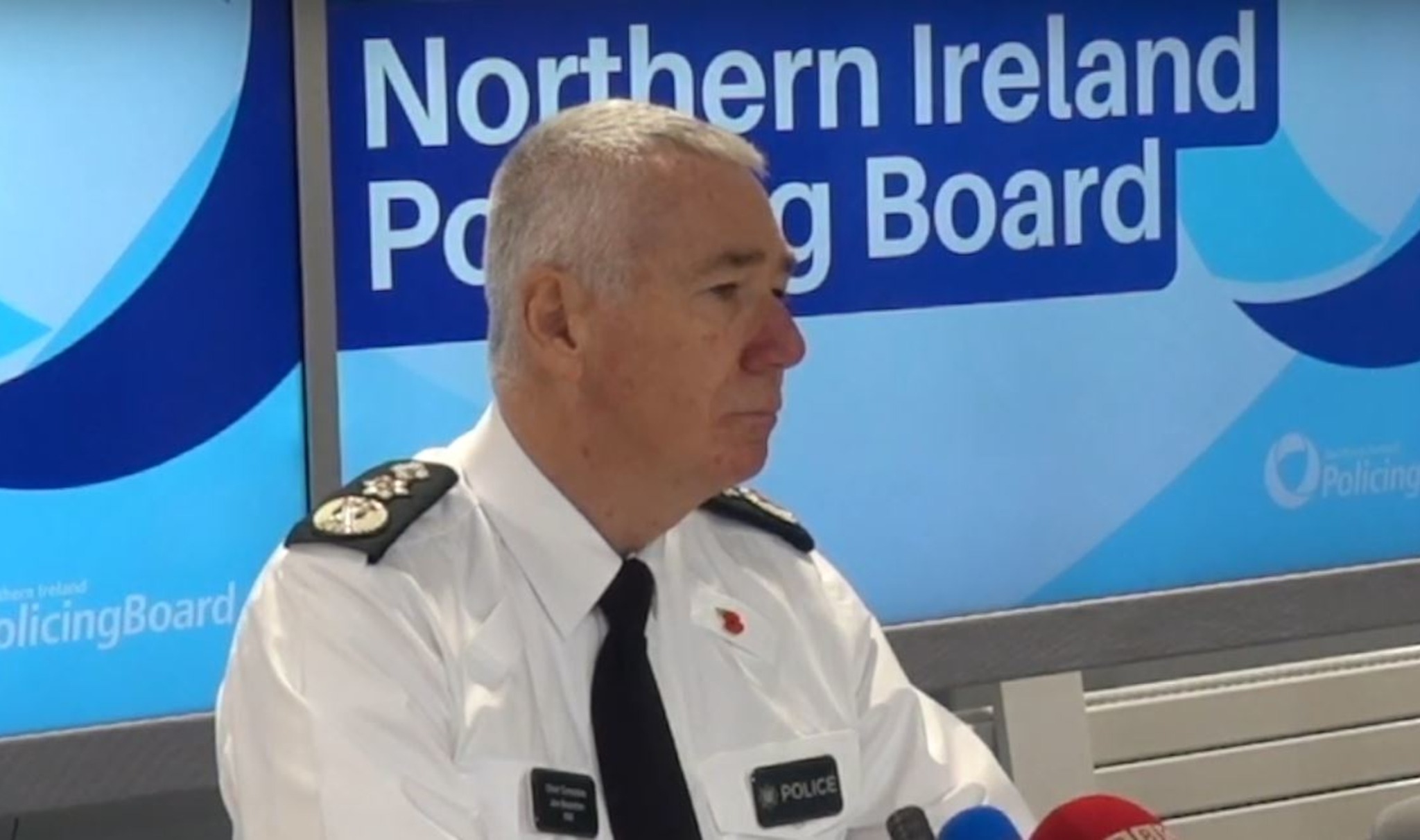

Operation Kenova, led by police chief Jon Boutcher, has spent the last seven years, and £40m, investigating 101 murders and abductions linked to the British military double-agent known by the code “Stakeknife” – aka Freddie Scappaticci.

He was a Belfast man of Italian extraction who headed up the IRA’s “Internal Security Unit” (or “nutting squad”). An army commander in Northern Ireland, General Sir John Wilsey, called him the “goose that laid the golden eggs”.

This prized agent, who the intelligence services had slavishly protected for years and credited with saving “hundreds of lives” by supposedly penetrating the IRA’s inner circle, is now exposed as a third-rate illusion.

Within the intelligence services, a “maverick culture” was created, Boutcher says, where agent handling was considered a high stakes “dark art” that was practised “off the books”.

Decades of grief, anguish and agony were the result, suffered by the families of those whom Scappaticci decided must be killed – their names forever tarnished in the eyes of their community.

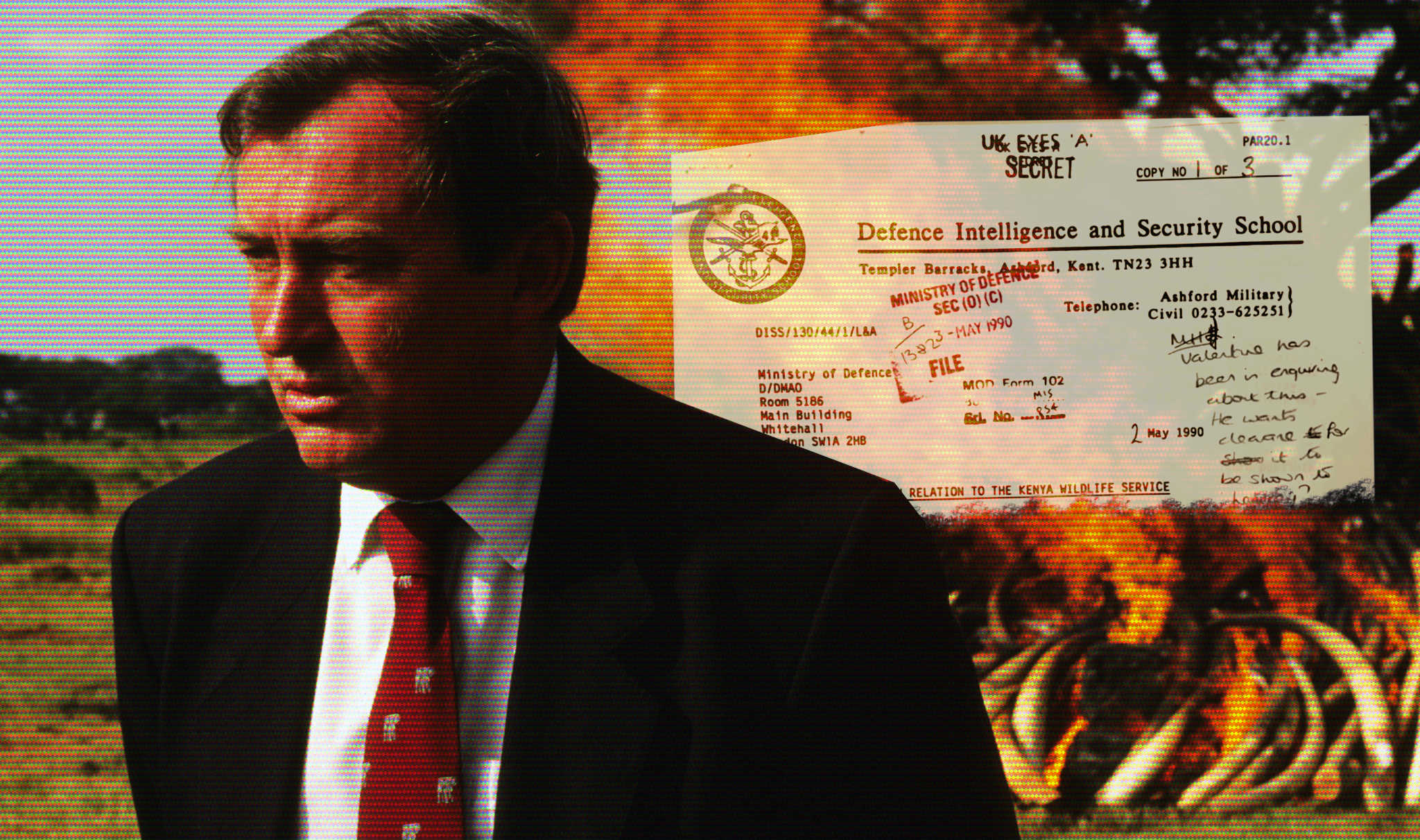

The IRA stood Scappaticci down, under suspicion, in 1990. He was “outed” in 2003 and moved from Belfast. He died in 2023 (Boutcher assures us of natural causes, denying conspiracy theories that he is still alive).

Cost more lives than he saved

One of the report’s most serious conclusions is that the impunity (enjoyed by Scappaticci, his handlers and others) was discussed at Cabinet level during the conflict and continued, without regulation or legal framework, until six years after the IRA ceasefire of 1994 and two years after the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

Once the “rose-tinted spectacles”, the “fables” and the “fairy tales” are dispensed with, the Kenova Report concludes Scappaticci probably caused more deaths (around 14) than he saved – a figure assessed at between “high single” and “low double” figures.

Kenova passed 32 files recommending prosecution for murder, kidnapping and torture to the Public Prosecution Service of Northern Ireland (PPSNI) but no-one will be charged after “glacially”-slow consideration by that office, although this clearly rankles with Boutcher.

Those he accuses in his report of serious crime are unnamed but include 16 IRA members, 12 retired military intelligence officers, two MI5 people, a former police officer and a member of the PPSNI itself. Civil actions, yet to pass through the courts, may reveal their details.

Boutcher pulls no punches in his coruscating report, condemning the IRA for using torture to obtain “confessions” and for brutalising, inter alia, children, vulnerable adults and people with learning difficulties.

The extent of inter-agency rivalry can be seen when Boutcher reveals that one MI5 officer gave his opinion that Stakeknife’s handlers in the army’s Force Research Unit (FRU) were “Gung ho”. Boutcher cites a commanding officer in the FRU, returning the serve, claiming everything it did was known to MI5.

When observing the record of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Special Branch, Boutcher characterises it as a self-serving “cabal … fiercely resistant to any form of scrutiny or oversight based on claims about a paramount need for secrecy”.

It was routine practice, he says, for Special Branch to treat intelligence as its own property, refusing to share it with criminal investigators, even if that meant offenders going free. This meant the greater good, “maintaining a stable and democratic society”, was eroded by state agents committing crimes with impunity.

Getting away with murder

Although little in Kenova is truly shocking for seasoned observers of what passed for law and order during the conflict in Northern Ireland, it is nevertheless deeply depressing to see, in black and white, a conclusion that “murders that could and should have been prevented were allowed to take place with the knowledge of the security forces and those responsible for murder were not brought to justice.”

Scappaticci himself emerges from the report, not as a redeemed terrorist who took risks to save life but as a sordid torturer and executioner found to be using extreme child pornography.

On a more positive note, Boutcher claims his report shows independent, robust legacy investigations can bring relief and consolation to grieving families. Reconciliation without such investigations, he says, is impossible – a dig at the British government’s recent Legacy Act.

Anyone hoping these Augean stables have finally been cleaned by Boutcher’s yard-brush should think again.

Another investigation, dubbed “Operation Denton”, also conducted by him over the last five years (before his elevation as Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland) is continuing under the former head of Police Scotland, Iain Livingstone.

This investigation, due to report later this year, is reviewing state collusion with loyalist paramilitaries in the murders of ten times the number of people whose deaths were linked to Scappaticci.