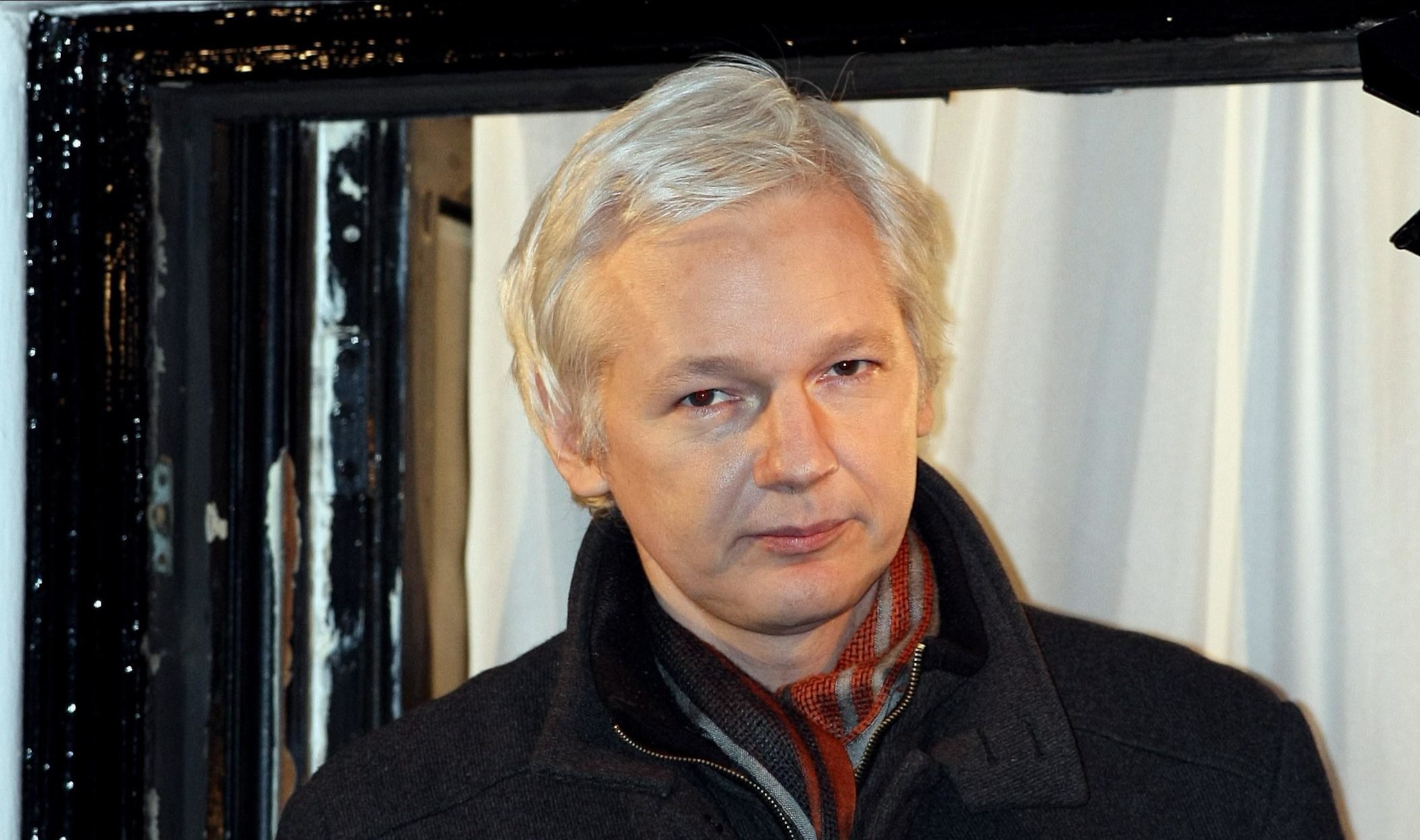

While watching Julian Assange’s appeal against extradition in London last week, I experienced complete déjà vu.

I worked as a journalist in Turkey for 37 years and have been living in exile in Berlin for seven years.

The reason I had to leave my country was a news report I wrote in 2015. After that report was published, my life changed completely.

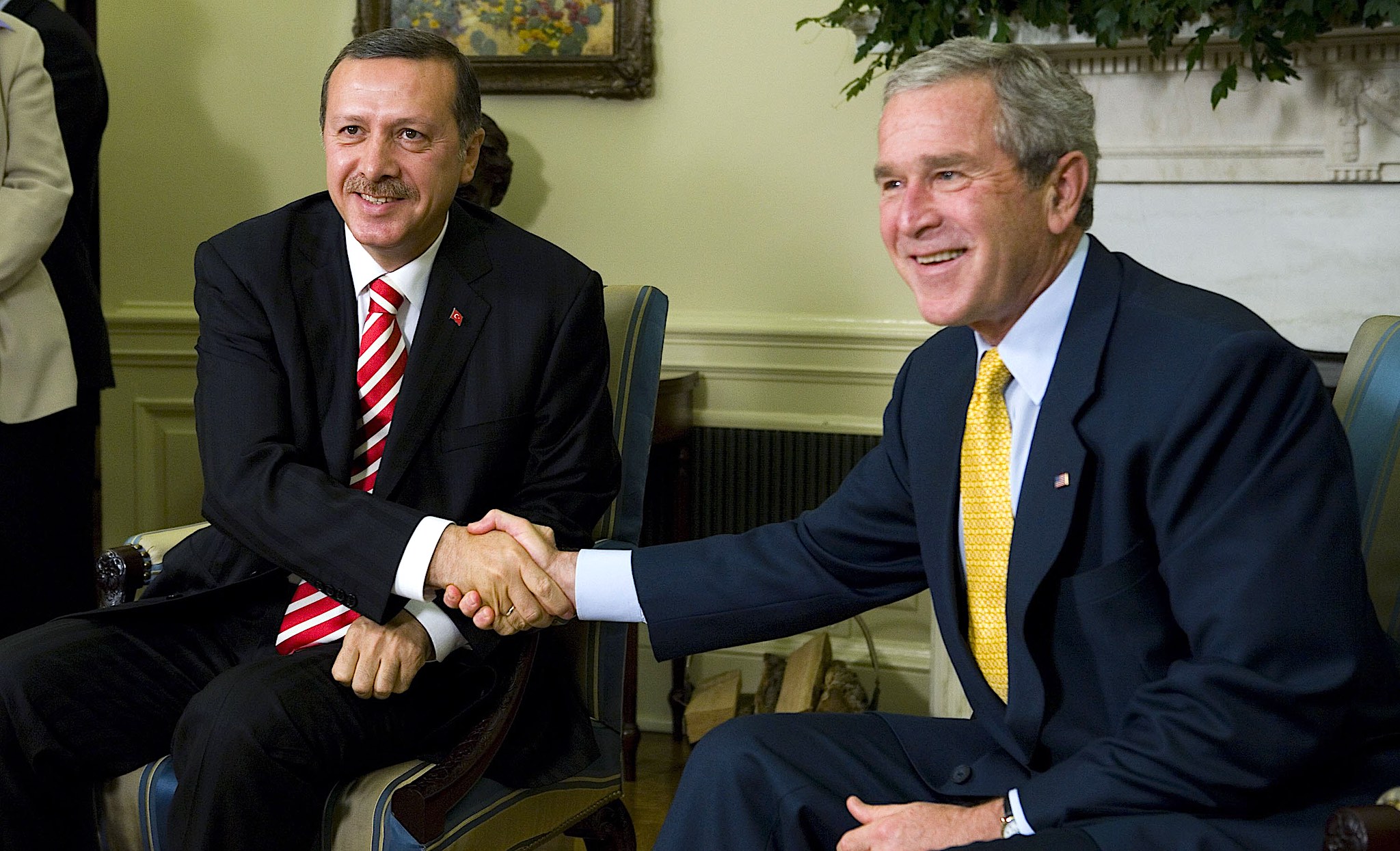

I became a target of President Erdoğan and his intelligence agency. Pro-government media labelled me as a “Turkish Assange”.

I was the editor-in-chief of Cumhuriyet, Turkey’s long-established, left-wing newspaper.

At the time, Turkey was accused of sending arms, ammunition, money and people to jihadist organisations in Syria.

But the government persistently denied these allegations, saying “We are only sending humanitarian aid”.

Finally, we received evidence proving this illegal transfer. It was a video recording.

Although it was not as awful as the “Collateral Murder” video published by WikiLeaks, it revealed the crime the state was hiding.

Arming terrorists

In the video, three trucks travelling towards Syria were stopped by the gendarmerie. It was understood that the drivers were Turkish intelligence (MIT) officers.

Despite their objections, the gendarmerie opened the crates of the trucks and found thousands of mortar and artillery shells hidden under medicine boxes.

MIT was not legally allowed to transfer arms. There were also strong indications that the ammunition had gone to ISIS. Despite the risk of arrest, we decided to publish the story.

On 29 May 2015, the newspaper came out with the headline: “Here are the weapons Erdoğan said did not exist”.

A publication ban was immediately imposed, but it was too late. The prime minister was forced to confirm the arms transfer.

“But they were going to the Free Syrian Army,” he said. However, the border gate across which the weapons were travelling was under the control of al-Nusra, an al-Qaeda affiliate.

Two days later, Erdoğan described the news as “an act of espionage” on live TV. He said: “The person who made the report will pay a heavy price for it. I will not let him get away with it.”

Apparently the “secret” was his, not the state’s.

Although arrest warrants were issued for the gendarmes, prosecutors and police officers who stopped the trucks, I was not arrested immediately, because there was an election coming up.

Arresting an editor-in-chief before the elections would not look good.

State secret

In the months following the news, Turkey experienced one of the bloodiest periods in its history.

ISIS suicide bombings killed 33 people in July and 102 in October. The total death toll reached 862 in five months.

Erdoğan had asked for votes to stop the bloodshed. He won the election with 49.5% of the vote. Shortly after, I was summoned by the prosecutor.

The accusation was this: “Obtaining state secrets for the purposes of political and military espionage, revealing information relating to the state security for the purposes of espionage, seeking to overthrow the government by force.”

It was all in one story. A true story.

“Conditions in my cell in Turkey, a one-man autocracy, were much better than in Assange’s cell in the UK”

The intelligence service had been caught red-handed and intended to take it out on the person who wrote the piece.

The sentence against me was two aggravated life sentences. If the death penalty had not been abolished, I would have been hanged.

I asked the prosecutor, “If this operation was a state secret, how was I supposed to know that it was a secret?”

Besides, journalists are not civil servants; their job is not to hide the dirty secrets of the state, but to inform the public about this danger.

I was arrested that day and locked up in Silivri Prison, which Reporters Without Borders described as “the world’s largest prison for journalists”.

It was a high-security prison (like Belmarsh). I was alone in solitary confinement (like Assange), but truth be told, the conditions in my cell in Turkey, a one-man autocracy, were much better than in Assange’s cell in the UK.

And because Erdoğan had not yet taken over the entire judiciary (he only succeeded after the coup attempt in the summer of 2016), the higher judges were more loyal to the rule of law.

Biden’s double standards

In the meantime, US vice president Joe Biden came to visit Turkey. He invited my wife and son to meet with him just before meeting with Erdoğan.

On 22 January 2016, after asking my son about my situation, Biden said: “You have a very brave father. You should be proud of him.”

He said they were doing everything necessary for freedom of the press.

Then he mentioned Thomas Jefferson’s famous quote: “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.”

It was the same Biden who later described Assange as a “hi-tech terrorist”. I think the reason for the different approach was that it was MIT, not the CIA, whose secrets were revealed.

According to the US side, the real reason was that “Assange was not a journalist”.

The then US ambassador, John Bass, who visited the paper when I was in prison, said the following upon being reminded that his government was also pursuing Edward Snowden.

“Yes, we are accused of inconsistency and hypocrisy for continuing to press charges against Snowden, but we do pursue Mr. Snowden for breaking the US law. But we have not prosecuted American journalists who published the sensitive information he had leaked.”

Isn’t that exactly what WikiLeaks did? Who was to decide whether Assange was a journalist or not?

Shooting the messenger

One month after the Biden-Erdoğan meeting, I was released as a result of the Constitutional Court’s decision that “the detention is unconstitutional.”

Erdoğan was furious. In his statement that day, he said, “I do not accept the decision, I do not respect it, I do not obey it”.

But he had to obey. I returned to my newspaper. The trial continued. Three months after my release, we attended the final hearing.

I was waiting outside with my lawyers and family. That evening, I was attacked by a gunman in the most protected place in Istanbul, in front of the courthouse.

The attacker shouted “traitor” and fired two shots. I survived thanks to my wife jumping on him.

Later I learnt that the attacker belonged to a mafia group linked to the MIT, meaning that the intelligence service had planned to close this case with an assassination (just like in the case of Assange).

That day, I was sentenced to 27.5 years in prison. We appealed the verdict.

That summer, while I was on holiday in Spain, there was an attempted military coup in Turkey. Erdoğan bloodily suppressed the attempt, saw it as “a favour from God” and turned it into an opportunity.

The next day a witch-hunt and arrests campaign began. My name was first on the “list of journalists to be arrested”.

Two of the thousands of detainees were the senior judges who ordered my release.

My lawyers advised me to stay abroad for a while. I have been in exile for seven years.

Journalism is not a crime

Assange knew that the CIA would follow him “to the end” because of the dirty secrets he revealed. Erdoğan did the same. He asked Germany to extradite me.

At a press conference during his visit in 2018 to Berlin, he told Chancellor Merkel that I was a spy. Merkel disagreed. The German government stood firm.

The German Foreign Office responded to Ankara’s extradition request by saying, “In principle, we do not extradite in cases of political convictions”.

Foreign minister Heiko Maas said that my conviction was “a harsh blow to independent journalism” and added: “Journalism is not a crime, but an indispensable service for society”.

I think now you can understand why I experienced “déjà vu” in the London courtroom.

Wherever in the world you reveal a dirty secret of the intelligence agencies or ruling elite (regardless of autocracy or democracy), the whole establishment comes after you.

They hope that the punishment will serve as a lesson for those who dare to do it again, and deter potential whistleblowers.

Still, I think Turkish autocracy is more merciful than British democracy.

At least at my trial there were no cages in the courtroom, and there was a separate toilet in my prison cell.