The government’s new ministerial ethics adviser, Lord Geidt, secretly supported one of the Middle East’s most repressive rulers, Declassified has found.

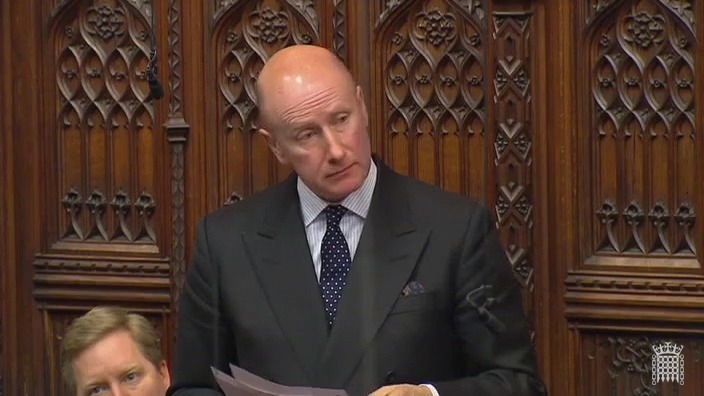

As a former top aide to the Queen, diplomat and army intelligence officer, the government claims Christopher Geidt has a “distinguished record of impartial public service”.

They believe he is the right man to investigate whether Boris Johnson and his ministers are compromised by private interests, including the recent controversy over who stumped up £200,000 to redecorate the Downing Street flat.

But Geidt himself has questions to answer about transparency. He sat on the Sultan of Oman’s Privy Council, a role he never declared to Britain’s parliament despite making advisory trips to the Gulf state in 2018–19 while sitting in the House of Lords.

The Oman Privy Council position involved advising Sultan Qaboos on how to run the country’s economy, security and foreign policy.

By the time he died last year, Qaboos was the Middle East’s longest serving autocrat, having ruled Oman since 1970 when he came to power in a British-led military coup.

Throughout his reign, all political parties were banned, independent media was muzzled and critics were jailed for the crime of “insulting the Sultan”.

Geidt’s secret trips to advise Qaboos are now the subject of a complaint filed with the House of Lords standards commissioner by an Omani exile and torture survivor.

Geidt did not reply directly to Declassified’s repeated requests for comment about the issue.

The Cabinet Office, which appointed Geidt to the new role, maintained he had done nothing wrong in his dealings with Oman’s late dictator, telling Declassified: “Lord Geidt has fully complied with his obligations under the Code of Conduct for Members of the House of Lords.”

Cheap flights?

The code requires Lords to register “all relevant interests, in order to make clear what are the interests that might reasonably be thought to influence their parliamentary actions”.

There are some exceptions to the rules and the Cabinet Office has suggested Geidt’s visits to Oman in January 2018 and January 2019 cost less than £500 — putting them below the threshold which must be declared.

However, the Cabinet Office refused to comment further when Declassified pointed out Geidt’s trips could have cost thousands of pounds.

Sir Alan Duncan, an ex-Foreign Office minister, claims in his recently published diaries that Geidt travelled to the first meeting from Stansted airport onboard the Sultan’s Gulfstream jet, a £44-million luxury aircraft that has seats for fewer than 20 people.

Upon arrival at the palace in Muscat, hospitality available to the Sultan’s Privy Council included high-end wines such as Petrus and Cheval Blanc. These can cost several hundred pounds a bottle.

Duncan, who travelled to the meeting with Geidt, recorded the trip in his MP’s register of interests as involving “one night’s accommodation and flights to and from Muscat worth £1,500” – three times above the costs threshold.

The Foreign Office has said it “did not approve Sir Alan Duncan’s attendance” at the Sultan’s Privy Council as he made the visits “in a private capacity”.

Although Geidt did not tell the House of Lords about his January 2018 trip to Oman, he did register an overnight visit to Macedonia a few months later in April 2018.

This was “at the invitation of the Prime Minister of Macedonia”, with “travel and accommodation paid for by the government of Macedonia”.

Geidt did not specify the cost of travelling to Macedonia, but the Balkan state is three times nearer to the UK than Oman, suggesting his flights would have cost significantly less than the journeys to Muscat.

Working for who?

The Cabinet Office also suggested to Declassified that Geidt’s visits to Oman were unconnected with his membership of the House of Lords and were made as part of his “employment or profession”, which is another scenario where peers do not have to declare external meetings.

However, the Cabinet Office then refused to clarify in what capacity Geidt made his trips to Oman if not as a peer.

Geidt had stopped working for the Queen before becoming a Lord and at the time of the first visit to Oman in January 2018 had no financial interests registered, suggesting he was not employed by anyone.

He did declare four non-financial interests or voluntary roles, namely chairing the Queen’s Commonwealth Trust and the council of King’s College London, and being a trustee to the Coutts Foundation and the Queen Elizabeth Diamond Jubilee Trust.

But it is unclear how these unpaid positions relate to Oman. Chris Kelly, the chief executive of the Queen’s Commonwealth Trust, told Declassified: “I can confirm that Lord Geidt is the Chair of the Queen’s Commonwealth Trust. This role has no association of any kind with Oman.”

The Diamond Jubilee Trust is no longer active, so Declassified has not been able to ask whether Geidt attended the Sultan’s Privy Council on their behalf. However, it seems unlikely as the group was focused on the Commonwealth, to which Oman does not belong.

King’s College and the Coutts Foundation, an anti-poverty charity which mainly supports women and girls, did not respond when asked whether Geidt attended the Sultan’s Privy Council on their behalf.

King’s College requires its council members to declare any external interests with the university, and the available register shows Geidt has not declared any role in Oman.

Even if Geidt had attended the Sultan’s Privy Council on behalf of one these organisations, there is still a case to argue he should have declared it to parliament.

For example, another member of the House of Lords, Lord Astor, declared his own visit to Oman for the Sultan’s Privy Council in 2017, even when Astor’s professional role included being a UK trade envoy to Oman for the prime minister.

Other British attendees at the Sultan’s secret Privy Council have included four serving Chiefs of the Defence Staff, covering the periods 1998-2001 and 2014-19.