Wilson Kiget’s mother Lydia was just 13 years old when she was first raped by a white farmer in Kenya. The assault came during British colonial rule in the 1930s, after the settler helped himself to the family’s fertile land.

“My mother worked on his tea plantation for ten years,” Wilson explains nervously. “She was raped continuously. Three of us were conceived by him. But when he wanted to marry a European woman, we were chased away and had to live in an abandoned hut.

“The horrible thing was whenever she went out with my siblings, who were lighter skinned than me, other children would run away because they were scared of their appearance. My mother died a miserable death.”

Wilson’s family languished in poverty for decades, while the tea planted on their land made a fortune for its British growers, Brooke Bond. The company would be acquired by UK food giant Unilever in 1984, who marketed the tea to millions of customers under the brands PG Tips and Lipton.

When Unilever sold its Kenyan tea investments to a private equity group in Luxembourg earlier this year, the deal was worth €4.5 billion. But now in an extraordinary twist, Wilson’s community – the Kipsigis tribal group – believe they could be about to reclaim around 200,000 acres of lost land, and a century of profits.

The change in fortune is thanks to a recent ruling by Kenya’s National Land Commission, which found the tea estates should have been returned to their original owners when the country became independent from Britain in 1963. Although the tea companies will challenge the decision at Nairobi High Court next year, for now there is hope among the defiant Kipsigis.

“Our land was stolen during colonialism,” James Biy tells me, as we sit outside his father’s cabin on the outskirts of Kericho, western Kenya. Behind us lie thousands of hectares of rolling green hills, verdant with tea leaves – on land which should belong to his family.

“After independence our property was not given back to us,” James remarks. “So it wasn’t real independence. We’re still fighting for it.”

His father, Tito Arap Mitei, now in his nineties, can still vividly recall the community’s ordeal. “I was young when the British came and started forcibly taking our ancestral land. They burned down our houses and chased us away several times,” Tito says hoarsely, holding a wooden walking stick.

“Three of my sisters died because they caught strange diseases when we moved into uninhabitable areas. Eventually we were so hungry we tried to come back here, but the tea companies said we were trespassers.”

James finishes translating for his father before adding: “Between me and the British, who is supposed to be a trespasser?” He produces a document to prove he was taken to court – for collecting drinking water from his ancestral streams.

The family now lives on a scrap of land across the river from the tea plantations, with barely enough grass to graze a single cow. “We use firewood for heating, but we don’t have enough land to collect the wood from,” James’ mother laments. “If I go on the tea estate, I’m not even allowed to take a twig.”

The missing skull

The Kipsigis are the victims of one of the British empire’s most brazen and enduring land grabs. It began in the late nineteenth century, when the imperial power built a railroad from the port of Mombasa towards Kisumu on the shores of Lake Victoria.

Near the end of the track it passed the lush slopes of Kericho, where Britain ran into resistance from the Kipsigis and the Nandis – a closely related community based on a mountain ridge to the north. Although they knew the ground far better than the British, they were completely outgunned.

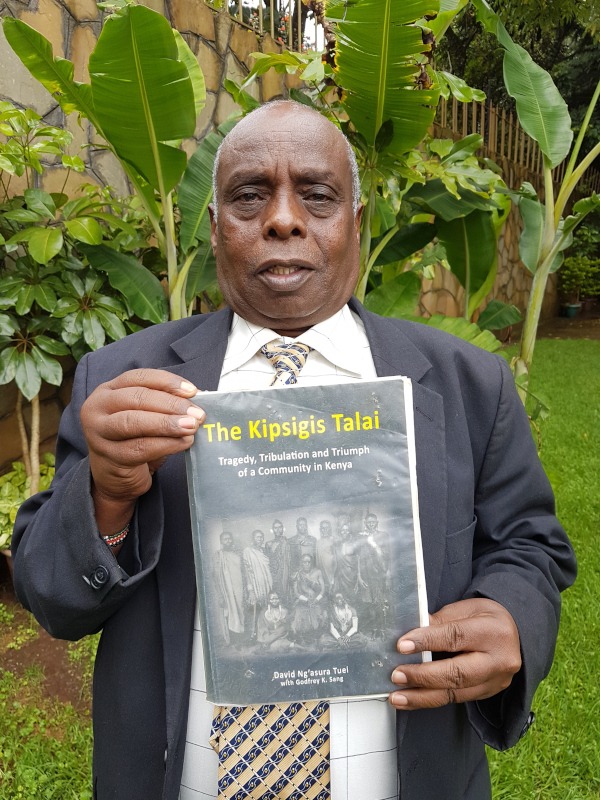

“In June 1905, 2,000 Kipsigis were lined up and killed by the British. They were massacred,” historian David Ngasura Tuei tells me. Crown forces fired more than 15,000 bullets on the punitive expedition to Sotik, in which they lost just one man. “The enemy was defeated with trifling loss to the column,” an official account notes dryly.

A few months after the massacre at Sotik, the Nandi’s leader Koitalel Samoei was killed by a British officer, Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen. His body was mutilated and belongings pillaged. A century later in 2006, the Colonel’s conscience-stricken son would return these artefacts to Kenya.

But Samoei’s skull is believed to still reside in England, although its exact location is unknown. The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford strongly denied a report that it housed the skull when I contacted them for comment, and it is not listed on their database of human remains.

While the Nandis’ resistance had been literally decapitated, the Kipsigis held out, forcing the British to try charming their royal family, the Talai. In 1906, their leader Kipchomber Arap Koilegen was invited to Mombasa to attend King Edward VII’s birthday celebrations. The British gave him an outfit to wear that emulated the style of the Sultan of Zanzibar, a powerful Arab ruler, denoting high status.

David Tuei, who is related to the Talai royal family and has written two books about their ordeal, says the British tried to get a treaty signed in Mombasa. “Kipchomber was told the King wanted peace and didn’t want the resistance to continue,” he outlines. “The settlers wanted the land and for the Kipsigis to be moved to what is now Tanzania.”

Unsurprisingly, these demands were rejected and resistance continued for another decade. Kipchomber and his two brothers were eventually detained and exiled to a distant part of Kenya, where they would spend their final days.

After the first world war, Britain’s land grab of the Kipsigis’ territory accelerated with the introduction of the British East Africa Disabled Officers Colony (BEADOC). It was a scheme for injured white war veterans to acquire 25,000 acres of farm land in Kenya.

While some Kipsigis had fought for Britain in WWI and received medals, that sacrifice was not enough to stop their ancestral soil being designated crown land. British agricultural companies then received 99 year leases: firms like Brooke Bond (bought by Unilever), James Finlay (now owned by Swire) and Williamson Tea. None of the tea companies responded to my requests for comment.

Kipsigis were retained as cheap labour or relegated to native reserves, where the ground was far less fertile.

Targeting the Talai

The most draconian treatment was handed out to the Kipsigis’ ruling family, the Talai. Fearing armed rebellion in 1934, King George V passed a removal ordnance banishing them to Gwassi on the shores of Lake Victoria, more than 80 miles from Kericho.

“When the Talai were rounded up, the British registered all 698 names,” David explains. “Then they trekked all the way to Gwassi – it took two weeks. The European escorts were pulled by ox and cart that carried their tents and food. But the Talai were on foot.

“My father was about 12 years old. He was carrying baby goats and sheep that had been born on route. Once they arrived there, 14 women had miscarriages. It was a harsh area, there were lots of snakes, mosquitos and flies. Most of the people in Gwassi died. That’s what the British wanted.”

When I ask David for proof of this chilling allegation, he calmly recalls a visit to the UK National Archives in London, where he unearthed a memo written by a British colonial official. It revealed a plan, “brutal as it may seem [to] leave the old men to die out gradually in Gwassi.”

The officer added: “I have little sympathy for the actual age group who made life so difficult for the government.”

“I was so shocked when I found this document,” David confessed. “I used to cry.” He lays out a sheet of paper in front of me, showing how the British carefully tabulated his community’s men, women and children before their deportation to Gwassi. The Talai’s birth and death rates were then recorded annually, instead of once a decade as was the norm for censuses in the rest of Kenya.

After wiping out the Talai elders, the next generation was to be tightly controlled. In 1945, a group of young Talai men were allowed to return to Kericho to marry Kipsigis women. “My father was among them,” David notes with some pride. “He is the only survivor who is alive – that trekked to Gwassi and came back. I was born in that detention camp in 1952.”

Those married in the camp were given a place in Kericho to await resettlement. “The life here in town was terrible. You weren’t allowed to keep cows or have enough land to plough. We used to go to Kericho Tea Hotel, which was for whites only, to scavenge for food. We ate the leftovers from the night before. We’d take it to our mothers who would re-cook it for the whole family.”

“Some young women started to sell their bodies to make money. That’s why when HIV came, it really hit Kipsigis Talai,” he adds.

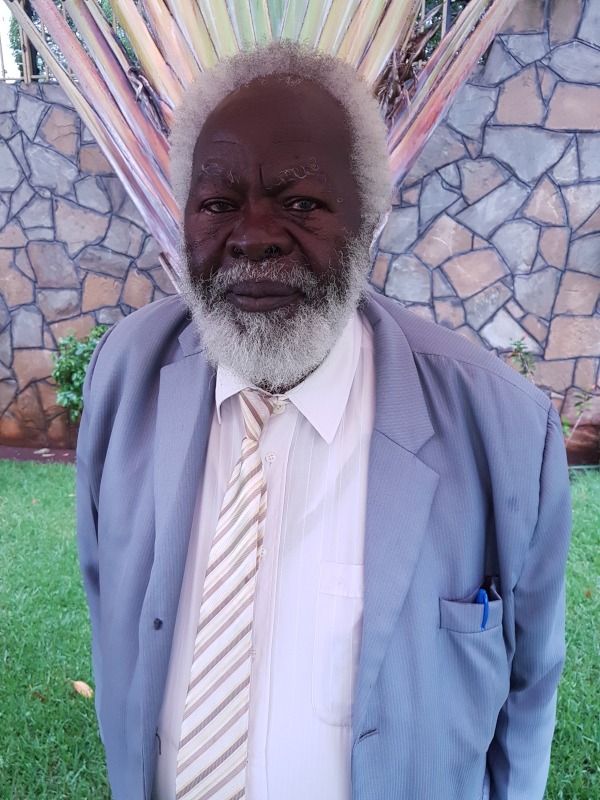

David is not the only person I meet in Kericho who grew up in a detention camp. Wearing a mustard suit jacket and with a clipped moustache, Stephen Kimeli Laboso describes how his family were driven from their land and detained in the 1950s when he was around ten years old.

“It was surrounded by barbed wire,” he recalls. His schooling finished at age eleven, after which he was used as cheap labour. “I had to work removing moles from tea plantations. They paid me only five cents a day,” Stephen says. “The coin had a hole in it with a symbol of the Queen.”

He then reveals an even darker episode. “There were old men who used to work as cooks at the camp. Sometimes they were sodomised by white men – Boers brought from South Africa,” he alleges. When the camp closed down in 1960, “eight elderly men decided to take their own lives by hanging themselves, because they didn’t have anywhere to go.”

“The Royal Family needs to listen to us before I die”

Elizabeth Rotich, 83, broke down in tears when she recalled her childhood. She was born in a village now occupied by Ekaterra (formerly Unilever and Brooke Bond). “We used to live there when the British came and told us to go away. We were called squatters, for living on our own farm! Our houses were torched with everything inside. I feel so bitter about it. We had to move and we didn’t have anywhere to go. I was hit trying to protect our livestock.”

Elizabeth, gripping a purple shawl, retains the courage to confront the old imperial power. “I’d like the British to listen to us and actually come to our aid, because we are still suffering. Even the son of Queen Elizabeth must know that there are some people here who are suffering. I’m sure her grandfather King George V told them as well.”

Turning to the current monarch, she adds: “I think King Charles III should ask for forgiveness, because it’s still within our hearts. That will be the start of a healing process, because it remains a scar.”

When I tell her that a student in York recently threw eggs at King Charles, yelling that Britain was “built on blood of slavery”, she laughs gleefully. “I’m very grateful that there are people with these feelings in Britain. The Royal Family needs to listen to us before I die.”

Buckingham Palace did not respond to my request for comment.

Colonial haunts

Kericho is mostly cloaked in mist during my visit. The rain clouds hang low over the verdant valleys, making it look like a scene from rural England. It’s no wonder white settlers felt at home in this climate, and began to make the town in their own image, constructing a golf club and other creature comforts.

The Kericho Tea Hotel, where David once scavenged, was built in 1950 by Brooke Bond to house British staff. It was the smartest establishment in town. Queen Elizabeth stayed in room seven shortly before her coronation was announced in 1952.

Today it is a crumbling relic. When I arrive, the barrier is unmanned and washing hangs from lines rigged between bushes on the driveway. Inside the reception, an eerie silence descends from its high ceiling. All the lights are off and no one is working there.

Back out by the porch, I meet three men who explain the hotel closed down a few years ago after a dispute between workers and management. It’s now rented out by local residents. The Queen’s old room, which I ask to see, is lying empty – and no one here has the key.

In the rest of Kericho though, the tea companies still cling to their former glory, in a town where the sun is yet to set on Britain’s imperial project. A colonial-era grey brick building towers over the main road, with long radio masts poking out from behind. Lipton’s logo hangs from the yellow gate, together with signs warning of 24 hour surveillance and injunctions not to carry pistols or take photos. I ignore the latter order, before pulling away.

Lipton’s lush plantations line one side of the highway for mile after mile, interspersed with 25,000 acres developed by James Finlay, another Scottish colonial tea magnate. “Anything on the left belongs to the whites. It’s known as the White Highlands.” Kipsigi community leader Joel Kimetto points out as he drives me through Kericho. “And on the right are the native reserves.”

These plots are typified by lines of drab single storey tin shacks, housing thousands of frustrated Kipsigis who graze cattle on the narrow verge. The tea pickers live in slightly better built bungalows inside the company grounds. Security guards, sometimes carrying weapons, patrol the perimeter and chase away anyone who gets too close.

“Anything on the left belongs to the whites. It’s known as the White Highlands”

“My car was nearly crushed by a metal barrier when we tried to visit our land inside the tea estate,” Joel complains. “We just wanted to see my ancestors’ graves.” Over the three days I spend in Kericho, interviewing at least 20 Kipsigis, the issue of burial sites is a deeply felt grievance.

Moses Mutai Munai, aged 86, exclaims: “We are totally forbidden from visiting the graves of our next of kin. There are barriers. And if we get in there by chance, they will call soldiers to harass us.” The town of Kericho was apparently named after Moses’ relative, who was a renowned healer.

“My ancestral land near Kericho town covers around 4,000 hectares,” he explains, his hair and beard turned white with age. “When Kericho was chased from around here he lost his business, he lost his land, and he lost nearly every property, so he became very poor. That’s why we, the grandchildren, are still suffering.”

Peter Bett, a school teacher, stresses the spiritual significance of the graveyards. “They destroyed our shrines where we used to pray and meet our ancestors. Where my grandfather was buried, the tea cannot grow. They’ve tried every trick in the book, but no tea has ever grown. There were trees the size of this room that my ancestors planted there.”

Peter’s grandfather, Tapsimatei Arap Borowa, was another prominent member of the Kipsigis. “He took the British to their own court three times and won two cases against the white settlers,” Peter marvels. The case centred on Kimulot, a 4,500 acre stretch of land belonging to 88 indigenous families. Several of the descendants, like Paulo Rutoh who left his home at 4 o’clock in the morning to journey to meet me, were driven away as far as Tanzania.

Although the Kimulot case was won in 1951, the tea company swiftly appealed. “My grandfather was imprisoned for nine months for refusing to let them take his land, before someone came and rescued him by paying a nine shillings fine,” Peter chronicles. Harsher fines and imprisonment would follow, and eventually their huts were torched on the orders of a British colonial policeman.

“It burnt for eight days,” Peter notes. “My grandmother and six other women remained in the ruins of their houses for more than a fortnight, during the rainy season. The settlers put boiling fat on her ears to try to get her to move. It was only when one of the children became very sick that she accepted to look for shelter among our relatives. Even today she’s scared to see a white man.”

As if wanting to prove this point, Peter guides me on a meandering journey down slippery dirt roads to meet his grandmother, Elizabeth Borowo, now 98. We enter a dark tin-roofed house with two mattresses on the floor. Lying on one is his frail grandmother. As Peter introduces me, she pulls up the bedsheet and tries to hide, haunted by the arrival of a white face.

Using the master’s tools

The colonisers not only wanted to acquire the Kipsigis’ territory. They also sought to remould their way of life, to prevent a future challenge to British rule. In this culture war, James believes language was a key battle ground.

“At school, I was told if I spoke my language I’d have to wear a disk on my neck as a punishment, because they wanted us to speak English,” he recalled resentfully. “It was brainwashing. They said our language was satanic. The British wanted to switch off the lights and destroy our culture, because we had a very strong culture.”

Joel runs me through how their leaders once managed the land. “There were no beggars. People were self-sufficient,” he says, evoking a pre-colonial golden era, when Kimulot was akin to Camelot. “There were areas for herds of livestock – cattle, sheep, goats – and bees. And a little bit of crop farming for vegetables, wheat and millet.”

Today these men are suspicious of attempts by all the tea companies to build schools and clinics in Kericho, seeing a pattern from the past. Joel regards it as a public relations ploy. “We don’t want Corporate Social Responsibility, we want the land back. They are building schools for us. If they give us our land, we can afford to do it ourselves.”

Despite this uncompromising attitude, Joel reveals he once worked for Unilever in its research department, where David too found a job in IT. Since leaving the company, the pair have turned their skills against Unilever, amassing a trove of evidence from official records to show how their land was stolen. Peter Bett, the teacher, also devotes himself to this enterprise.

“Our parents had to buy the English language for us by selling cows. It distorted our culture but benefitted us in another way,” Joel smiles. “They gave us knowledge to know the truth of the matters. They were writing these things in black and white, thinking our people would not be able to read it. But now we have read it, and we’ve understood it. That’s why we are asking for our rights.”

“In 2009, they wrote to Queen Elizabeth and asked her to compensate the Talai”

In 2009, they wrote to Queen Elizabeth and asked her to compensate the Talai. Buckingham Palace responded, claiming their message had been forwarded to Labour’s foreign secretary David Miliband. He never replied. Miliband now earns over a million dollars a year running the International Rescue Committee, a charity supposed to help displaced people.

Undeterred, Joel, Peter and David managed to bring Kericho’s governor, Paul Chepkwony, on side by 2014. He initiated a motion at the county assembly that Kipsigis and Talai should be compensated by the UK government. They then began to register the surviving victims of the land grab, around 120,000 people, and finally had the funds to instruct lawyers.

Among their barristers was Karim Khan, a British silk who is now chief prosecutor at the International Criminal Court. His appointment to the Hague was backed by the UK government. “At first Karim Khan sort of said we didn’t have a case,” David reflected. “But after we gave a presentation in Nairobi he was so excited and said this case has weight – it must go on.”

The lawyers scoured colonial archives in London, Nairobi and Entebbe, until the case was finally ready to be brought against the British government. But it was refused. “They said we should have brought it within 30 years of independence,” David notes sadly.

Yet such action was scarcely possible in Kenya during the aftermath of imperial rule. Presidents Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel Arap Moi, who between them ruled from 1964 to 2002, betrayed many promises of the anti-colonial struggle. Moi, in particular, pocketed land for himself across Kenya and governed autocratically.

“Sometimes the oppression which was done by the British colonial government was passed over to the Kenyan government”

“Why couldn’t they listen to us? They never even responded,” Joel laments. “Sometimes the oppression which was done by the British colonial government was passed over to the Kenyan government. But they underestimated us. We used to fear the government and they took that as an opportunity to take land. People got drunk on power. But there will be a time when enough is enough.”

In 2010, Kenya passed a new constitution, which Joel views as transformational. “Before that, we weren’t free. After 2010, we had freedom of speech – for the first time since the British banned our gatherings in 1905.” For him, it’s only been possible in the last decade to make these kinds of demands for reparations.

Despite the British government’s hard line on the time limit, London has been forced to settle other colonial-era claims from Kenya. Some 5,000 former Mau Mau suspects received £20m of compensation in 2013 for their barbaric torture by British troops at the end of imperial rule.

Perversely, Whitehall now uses that settlement to say all claims from the colonial period are resolved. This is despite the fact the Kipsigis did not take part in the Mau Mau uprising, which was dominated by the Kikuyu ethnic group.

A Foreign Office spokeswoman told me: “The UK Government recognised that Kenyans were subject to ill treatment at the hands of the colonial administration in 2013, and we regret that these historic abuses took place. Promoting and protecting human rights around the world remains a cornerstone of our foreign policy.”

Joel’s response is scathing: “The British do not deserve to be among the big nations talking about human rights until they give back our land.”

Changing tactics

With no way to bring a case in Britain, the Kipsigis’ legal team looked for other avenues to seek justice. They went to the United Nations, whose special rapporteurs delivered a stinging indictment in their favour last year. Another case is pending before the European Court of Human Rights, and further letters have been sent to the British royal family.

Most importantly though, they petitioned Kenya’s National Land Commission (NLC), which ruled that the land should have reverted back to the Kipsigis at independence and the tea company leases were void. This decision in 2019 set the stage for the community to reclaim the land – a move the tea companies are desperately trying to stall.

Unilever rebranded its East African tea estates as Ekaterra, which it then sold to a private equity group in Luxembourg, CVC Capital Partners Fund VIII. The €4.5bn deal was completed in July. Many Kipsigis question whether it was legal to sell the tea estates amid a court case disputing ownership. CVC did not respond to my request for comment.

Finlays and several other tea companies have lodged a judicial review application at the High Court in Nairobi, to try to appeal the NLC ruling. The firms represent a significant chunk of British investment in Kenya, and it appears that UK diplomats are lending them support behind the scenes.

British High Commissioner Jane Marriott met representatives from Finlays, Williamson Tea and Unilever in May 2021, when she hosted an International Tea Event at her residence. Heavily redacted documents from the event, obtained by Declassified, show Britain’s Department for International Trade was also involved in the tea party.

Officials aimed to “foster relations with the tea sector as well as government ministers” at the event. In preparation, diplomats researched what rights foreign entities had to own land under Kenya’s new constitution.

Even with the British government seemingly in league with the multinational tea companies, Joel is confident the land is within their grasp. “It would not be difficult for us to take it back by force, but we don’t want to go that route. We’ve been preventing our youth from causing damage. Let’s do it peacefully and use amicable language – because they are the same people we might be trading with.”

David, who is the lead claimant in the NLC case, adds: “We are not against British investment in Kenya, but we should be given the right to decide how the investors stay with us. We don’t want to be dictated to by the tea firms, who are taking all the profit. We want to benefit from the investment.”

Back in London, on the banks of the River Thames, it is easy to see where the wealth from Kericho now rests. Dominating the approach to Blackfriars Bridge is Unilever House, a neoclassical art deco building with a distinctive curved front which houses the company’s global headquarters.

Over the road, a statue of Queen Victoria faces the firm – keeping an eye on the legacy of empire.