When Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson successfully stood for election in December 2019, his party’s manifesto proudly proclaimed “we view our country as a force for good”, citing “our alliances with like-minded democracies” as a reason “for the UK to hold its head high”.

Why then, a little over a year later, is Britain propping up Yoweri Museveni, the 76-year-old authoritarian ruler of Uganda?

In power since 1986, Museveni won a sixth presidential term on Saturday after overseeing what the Economist called “one of the most violent election campaigns in Ugandan history”.

Museveni admitted that 54 Ugandans were killed last November alone. The figure is substantially higher than in Hong Kong, where around two people have died in pro-democracy demonstrations since 2019, but which have gained much more UK media attention.

The deaths in Uganda occurred during protests against the arrest of Museveni’s main rival, Bobi Wine, a 38-year-old pop star turned opposition leader.

Following his release, police fired at Wine’s car on 1 December, prompting him to wear a bullet-proof vest and helmet for the rest of the campaign trail.

Uganda’s media is not safe either. Amnesty International said: “Journalists in Uganda are facing an unprecedented level of violence and restrictions covering this election campaign where previously the authorities had allowed international media scrutiny.”

By the time the country went to the polls last week, the European Union and United States had cancelled their election monitors.

More than 75% of observers put forward by the US were denied accreditation by the Ugandan authorities, leading US Ambassador Natalie E Brown to lament: “With only 15 accreditations approved, it is not possible for the United States to meaningfully observe the conduct of Uganda’s elections at polling sites across the country.”

During the count, Uganda’s internet was switched off and soldiers surrounded Wine’s home, placing him effectively under house arrest — although the army claims it was for his own safety.

In statements smuggled out through intermediaries, Wine accused Museveni of “committing the most vile election fraud in history” and said, “our entire campaign team is in prison, they are being charged with trumped-up cases, while others are on the run.”

The US State Department said it was “deeply troubled” and “gravely concerned” by Uganda’s election violence, but Johnson’s government is more relaxed.

Britain’s Africa minister James Duddridge MP said on Sunday that the UK “welcomes the relatively calm passing of the elections in Uganda and notes the re-election” of Museveni.

While claiming to be a “steadfast advocate for Ugandan democracy” and expressing “concern” at the internet blackout, “which clearly limited the transparency of the elections”, the British government effectively endorsed the outcome.

Contrast this with the Foreign Office’s response to Bolivia’s election in 2019, when it gave credence to false claims that there were “substantial shortcomings” in the poll which “undermined their credibility and transparency,” requiring a second round of voting “to restore trust in the process and to fully ensure the democratic choice of the Bolivian people.”

As a result of this international pressure — and a military coup — Bolivia’s left-wing President Evo Morales was forced to step down, allowing a radical right-wing opposition politician Jeanine Áñez to become “interim president”, for which the UK congratulated her.

It later emerged there was no electoral fraud, and Morales had fairly won the presidency.

‘Go up a gear’

Despite Uganda’s election being held in much less transparent circumstances than Bolivia’s, the UK is prepared to give Museveni the benefit of the doubt — in keeping with Britain’s long-standing policy.

Aside from occasionally suspending aid to Uganda over corruption concerns, the UK has supported Museveni throughout his time in power, as his rule became increasingly authoritarian.

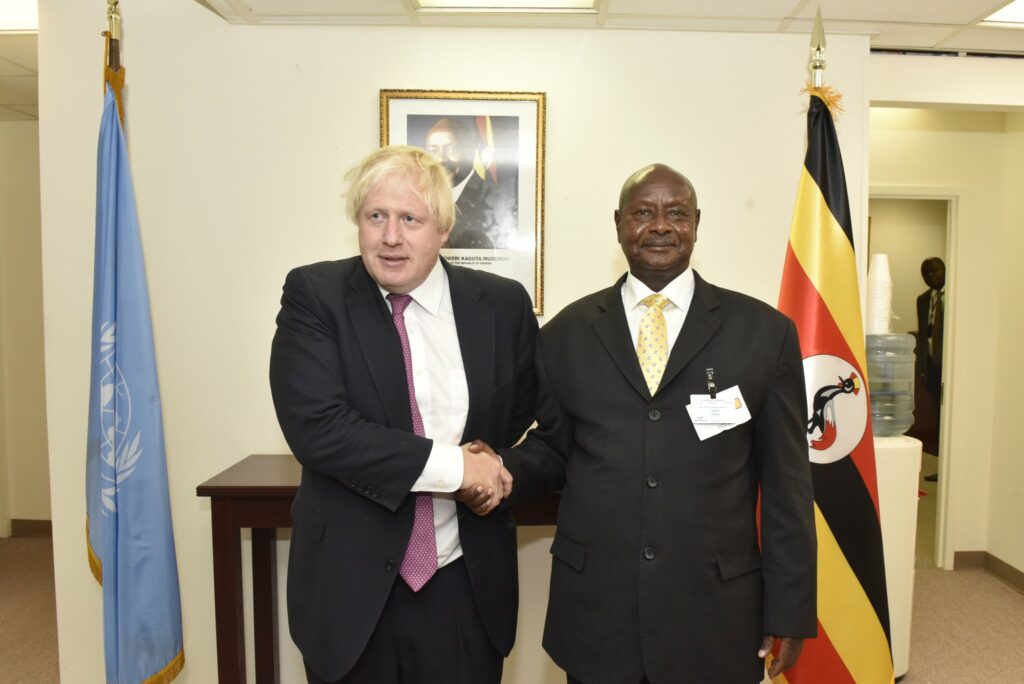

Johnson has met him on at least three occasions since 2017, including at a UK-Africa investment summit in London last January when he “spoke of the UK’s commitment and investment in Uganda and his desire to see the two countries’ trade relationship go up a gear”.

The summit took place months after Wine had been incarcerated in a maximum-security prison, in what Amnesty International called “a shameless attempt to silence him for criticising the government”.

British ministers seldom criticise Museveni in public, and in private they have lobbied him on behalf of Conservative Party donors — in one case attempting to cancel a £210-million tax bill levied in Uganda for UK oil company, Tullow Oil.

The company, whose founder and former chair has donated to the Conservatives, has had major investments in Uganda and its staff were treated to a visit by British military officers on a “study tour” in 2015.

An investigation by Corporate Watch found that Tullow’s former business partner in the country, British firm Heritage Oil, triggered a Ugandan army operation in 2007 that resulted in the deaths of six ferry passengers, including a three-year-old child, who were crossing Lake Albert.

UK diplomats are trusted to uphold the interests of British energy firms. The current High Commissioner to Uganda, Kate Airey OBE, spent six years working for Shell before becoming an “African energy adviser” at the Foreign Office where her job included “political analysis and lobbying Nigeria Oil and Gas”.

War on terror

Museveni endears himself to Europe and the US by offering foreign investors generous tax incentives and by claiming to be a bulwark against Islamic terrorism in East Africa.

Uganda was the first country to send troops to Somalia under the African Union mission to stop the terrorist group al-Shabaab in 2007, and maintains the largest contingent, with more than 6,000 soldiers in Somalia.

This contribution to the “war on terror” has earned Uganda training sessions from the British army and Royal Marines as recently as August 2019, when Wine was due in court on treason charges and his close ally, Michael Kalinda, was allegedly killed by state forces.

Kalinda’s left eye was reportedly gouged out and two of his fingers sliced off before his burnt and beaten body was dumped at a hospital in the capital, Kampala, where he later died.

A further 14 British military courses have been attended by Ugandan troops since 2018, including “civil affairs”, “building integrity for senior leaders” and intelligence, while spaces have been provided at the prestigious Sandhurst military academy.

Ugandan police forensics officers received UK training in dealing with improvised explosives as recently as 2019, when “human rights training” was also being provided to Uganda’s prison service. During the 1990s, Britain’s aid budget was used to supply Uganda’s police with 200 Land Rovers, as well as radios and identification equipment.

Britain has long acquiesced in Museveni’s crackdowns, and although arms sales appear to have moderated recently with the revocation of export licenses for combat helicopter parts, there is still plenty of UK-made equipment that can be used against Ugandan activists.

Following disputed presidential elections in 2011, Ugandan intelligence officials used surveillance gear sold by a British firm to spy on opposition activists and gathered “hordes of information”.

In 2006, Oxfam claimed that British arms giant BAE Systems had sold armoured vehicles to Uganda via a South African subsidiary. The vehicles were allegedly used to disperse opposition protesters during that year’s disputed election.

Britain has also supported previous repressive regimes in Uganda, welcoming the military coup by Idi Amin 50 years ago this month and allowing UK mercenaries to train special forces under the government of Milton Obote, Amin’s successor.

While Britain’s media has reported Museveni’s crackdown on Bobi Wine, such stories are not awarded the same air time or column inches given to opposition activists in countries led by Western adversaries.

Since Wine announced he was running for Uganda’s parliament at a by-election in April 2017, his name has been mentioned in 39 articles by The Times.

Over that same period, The Times named Hong Kong pro-democracy activist Joshua Wong in 94 articles — nearly two-and-half times more often than Wine, according to a search of the Nexis database.

Similarly, Russian opposition leader Alexi Navalny has been mentioned in up to 600 articles by The Times since April 2017.

His recent arrest upon return to Russia was pictured on the front pages of three British newspapers on Monday, with UK foreign secretary Dominic Raab tweeting out a press release saying: “It is appalling that Alexey Navalny, the victim of a despicable crime, has been detained by Russian authorities. He must be immediately released.”

At the time of writing, Raab has remained silent on Wine’s house arrest.

Angelo Izama, a Ugandan writer and analyst, told Declassified: “The position of the UK Foreign Office is tepid, unimaginative and at odds with the extreme events in Uganda.”

He added: “The United Kingdom, as far as Uganda is concerned, is wedded to the tried and tested — or if you like the establishment. It is a functional relationship which while projecting UK interests in the most minimum of terms — commercial opportunities for British firms and security interests — is also useful for British politicians, no matter the party. It is also a reciprocal relationship where the Uganda government expects diplomatic support and British aid and commerce.

“However in the last decade, the government of Uganda has not relied upon this support, thus Britain only has titular status as a former colonial power but has lost out to changing circumstances in Uganda including a more sustainable economy powered in no small part by Chinese loans.”