Recently declassified files reveal Britain’s covert propaganda in support of NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia from March 1999.

Air strikes by NATO forces lasted until June 1999 when an agreement was reached leading to the withdrawal of the Yugoslav army from the province of Kosovo.

The UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) files demonstrate the objective of British media operations was to convince the British and Serbian publics that NATO’s illegal 78-day aerial bombing campaign of Yugoslavia – known as Operation Allied Force – was “a just cause”, and that its military forces were indomitable.

To this end, Downing Street staff and civil servants developed a coordinated network of media strategists and secretive units to furtively disseminate NATO propaganda through media outlets in Britain and the Balkans.

The UK military also sought to “influence the behaviour” of Yugoslav forces by way of psychological operations (psyops).

NATO argued its intervention in Yugoslavia aimed to halt the alarming fatality rates reported by Western officials, with estimates of 100,000 Kosovar Albanian men killed in a region roughly the size of Yorkshire.

Crimes committed by the Yugoslav army and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) which it opposed, are documented in the files, though official investigators failed to find evidence of massacres that was anywhere near the scale espoused by Western officials.

Additionally, NATO’s aerial supremacy was seriously challenged by heavy cloud cover and the ability of Yugoslav forces to evade air strikes. NATO’s bombs were ineffective at swiftly halting the violence and in fact exacerbated the death and displacement.

NATO and British propaganda would therefore prove paramount in attempts to legitimise military adventurism under the pretence of humanitarian intervention.

‘By message, and the means’

A letter dated 15 April 1999 from Downing Street press secretary Alastair Campbell to Tony Blair’s chief of staff Jonathan Powell, made clear that British planners considered “control and coordination” of NATO’s media campaign as vital.

Campbell stated this was “because the propaganda battle is not just won by fact, but by message, and the means by which the message is deployed”. In relation to Allied Force, he added that “the message is simple. This is a just cause. We are going to win”.

“Every big campaign requires a press article factory”

Campbell also proclaimed: “The key to message delivery is the creation of those events and stories. This requires making the most of what the military are doing”.

“Every big campaign requires a press article factory. Not a day should pass without us having authored or heavily influenced, comment/editorial pieces in every major country”, he continued.

‘Achieving best coverage’

In tune with Campbell’s modus operandi, a file from earlier that month reveals that a “blitz of arguments and articles” had already been planned for national media by Campbell’s deputy press secretary, Godric Smith.

One proposal for the Sunday Telegraph, read: “Chancellor Schröder on why Germany felt it had to act” and noted that “counterparts in Germany” were “in liaison with” the Foreign Office. Another was for “an anonymised pilot in action over Kosovo for Saturday’s Sun”, which was to be delegated to the “MOD to process”.

The files show that strategy for UK regional media was to be coordinated by the MOD’s director of information strategy and news, Oona Muirhead. Muirhead later described her role as being “behind the scenes” ensuring the “system worked” and that the MOD’s “media operation operated effectively”.

Efforts were made to identify “key regional editors to be targeted” for briefing, “feeder services” for local radio pieces, and “’talking heads’ with local credibility” for TV.

Here, the government’s opaque Strategic Communications Unit was to provide “key contacts” and support toward “achieving best coverage”.

‘Editorial control’

In a letter in early April, Britain’s chief of defence staff, Sir Charles Guthrie, pleaded with NATO supreme commander Wesley Clark that British politicians be permitted “to engage the enemy on the public relations front with sufficient ammunition”.

By the end of that month, British efforts in this area escalated, the documents indicate.

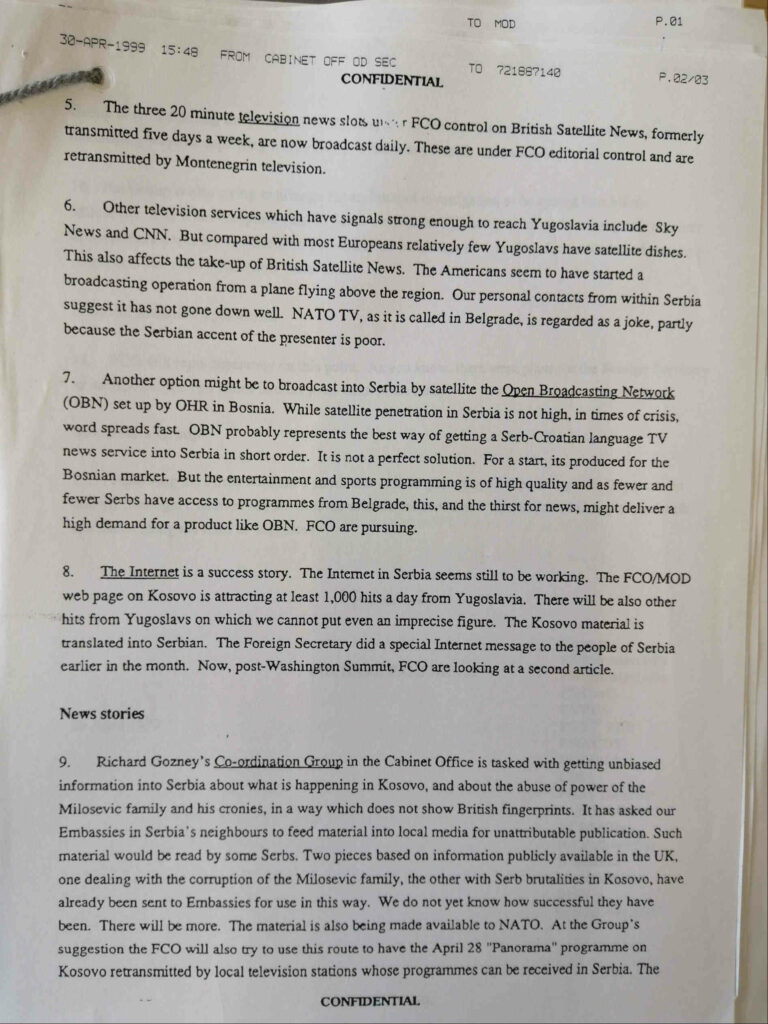

A letter from the chair of the Joint Intelligence Committee, Michael Pakenham, assured Blair’s foreign affairs adviser, John Sawers, that the Foreign Office “put substantial effort” into increasing news broadcasting to Serbia.

In addition to more BBC World Service broadcasting, the files note increased output from British Satellite News (BSN), with BSN daily news slots “under FCO [Foreign Office] editorial control” being “retransmitted by Montenegrin television”.

Established in 1992 and self-described as “a free television news and features service”, BSN operations were entirely funded by the Foreign Office.

The service was designed to project a “British perspective” of world events, and its content is reported to have been in use by 400 news channels globally by 2003.

‘British fingerprints’

Further revealed by Pakenham are the activities of a “Coordination Group in the Cabinet Office”, chaired by Sir Richard Gozney, the chief of assessments staff.

The group was “tasked with getting unbiased information into Serbia” about events in Kosovo and the “abuse of power” by Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic “and his cronies”. This was to be done “in a way which does not show British fingerprints”, Pakenham noted.

“It [the Group] has asked our embassies in Serbia’s neighbours to feed material into local media for unattributable publication. Such material would be read by some Serbs”, he continued.

A letter to Sawers from foreign secretary Robin Cook’s principal private secretary, John Grant, acknowledged the group’s Foreign Office representative was David Landsman, formerly the deputy head of mission in Belgrade.

Pakenham’s letter also noted that: “The group is co-ordinating the compilation of a long list of Serbian internet users. Some agencies are developing ways of exploiting it effectively without any British hand showing”.

How this data was obtained and what is meant by “exploiting” is not made clear, nor what kind of operational remit such activities fell under.

A report published the year after Allied Force concluded there was “no evidence” the UK “made significant use of computer network attack [sic] against the Serbian military or civilian infrastructure” during the operation.

Without knowing how this list of internet users was obtained, or what the report constitutes as “significant”, it is difficult to ascertain whether computer network attacks were employed in British strategy.

‘15 Information Support Group’

Another document from mid-April authored by the MOD’s director of joint warfare, Brigadier Michael Laurie, detailed the deployment of 15 Information Support Group (15 ISG) to Macedonia.

Equipped with a “print facility”, 15 ISG were to be integrated into the US-led “Psy Ops campaign to support Op Allied Force”. Its commissioning officer was based in Naples, Italy under the Combined Joint Psy Ops Task Force (CJPOTF), where operations would be planned.

An MOD Allied Joint Doctrine for Psychological Operations has described the aims of these activities as “influencing approved target audiences directly”.

15 ISG’s foreseen contribution was to produce propaganda leaflets to be dropped over Yugoslav army positions and Serbia’s civilian population, and to “generate appropriate Psy Ops themes and messages for inclusion in other broadcasts”.

Laurie explained that 15 ISG “formed on 13 Mar[ch] 99 from 15 Psy Ops Group (15 POG)”. While 15 POG had only become a permanent unit the previous year, it was first established in 1991 following reported successes of British psyops efforts during the Gulf War against Iraq.

15 POG has described one success of its leafleting in Iraq as “strategic deception”, which “led Iraq to falsely believe that there would be a marine assault east of Kuwait”.

Laurie nevertheless upheld that under British defence doctrine the employment of psyops was “to use entirely truthful messages to influence the behaviour of enemy, neutral and friendly forces”.

Leaflets

One example of a leaflet dropped over Yugoslav army positions in April 1999 featured the image of an Apache helicopter in attack, even though the aircraft was not used in Kosovo.

Another claimed that “over 13,000 Yugoslavian service members have already left the armed forces”. To this assertion, Laurie lamented that “the CJPOTF in Naples will not disclose the source of their information, but its veracity is very doubtful”.

Many of the leaflets in Serbo-Croat dropped by NATO were full of grammatical errors and were reportedly seen more as a source of amusement than persuasion.

Similar anecdotal evidence suggests the linguistic quality of leaflets did improve as the operation wore on. However, those bearing threatening imagery and slogans would continue to be dropped over Yugoslav positions and civilian areas well after 15 ISG’s deployment.

Overall, it was concluded that the operations were wholly ineffective at forcing Yugoslav forces to abandon their positions and give up fighting or at galvanising Serbian public opinion in NATO’s favour.

Mobile news

Further emphasised in the documents is use of a “Mobile News Team (MNT) in Macedonia”, whose “local boy stories” in print and film about serving British soldiers were to be “effectively pooled to regional correspondents”.

Operating under Headquarters Land Command, the MNT was a media production unit of the British Army, and its productions from Macedonia are held in the Imperial War Museum’s archives.

Another meeting record noted that “a MOD film crew is onboard HMS Splendid”, the British Navy submarine that fired 20 of the 238 Tomahawk missiles launched at targets in Serbia during the campaign.

Since Operation Allied Force exclusively involved aerial bombing, reporters were unable to embed themselves with military units on the ground in Kosovo, as they and the MOD might have wished.

The year following the campaign, a parliamentary report noted this constraint, along with the demands of 24 hour news and a decline of defence reporters in the British press.

Media opportunity

This media environment, however, was noted as an “opportunity”, as “most journalists were unable to challenge the MOD line and relied heavily on official briefings for their copy rather than on a network of contacts or informed analysis”.

The report acknowledged the perception that NATO’s media messaging “exaggerated the effectiveness of air strikes” and admitted that “assessments of the damage done” to Yugoslav forces “were vastly over-estimated”.

“Most journalists were unable to challenge the MOD line”

Further recognised was the argument that “the Alliance wildly exaggerated the numbers of Kosovo Albanian civilians killed”. It conceded that “more could have been done to give accurate information about the actual number of killings in Kosovo”, and to “provide some corrective to the more lurid claims”.

Nevertheless, it noted that the MOD strategy was “successful” in “mobilising international and British public opinion”. Thanks to the “instrumental” role of Campbell, it stated British efforts were pivotal “in ‘rescuing’ the NATO media operation” and “leading NATO” in “steadfastness and purpose”.

‘Integration of Psy Ops’

Further recorded by Laurie is the continuing “integration of psyops” within planning of wider information operations, which incorporate the influencing of audiences outside of the purely military dimensions of psyops.

A report from 2001 noted that the UK’s information operations strategy was “immature at the time of the Kosovo campaign”. It stated that considering “lessons learned”, the MOD had put in “new structures” to accelerate “integrating information operations and targeting”.

In another report from 2004, former MOD chief of information operations, Air Vice-Marshall Heath, stated that psyops were “very much a part of Information Operations” but maintained they are “specifically military” and “specifically tactical”.

Around 2004, 15 ISG would readopt its former title of 15 POG before ultimately being absorbed into the army’s psyops unit the 77 Brigade in 2015.

A Big Brother Watch investigation last year revealed the 77 Brigade had spied on dissident academics, journalists and activists, especially during lockdowns.

A brigade whistleblower wrote: “I entered this role believing I would be surfacing foreign information warfare against our country. Instead, I found the banner of disinformation was a guise under which the British military was being deployed to monitor and flag our own concerned citizens to the government”.

Operation Allied Force would have grave consequences for the people of Yugoslavia. But the propaganda campaigns waged in its support would also set new precedents for civil surveillance in Britain.