Britain’s promotion of “news” services in the Middle East was driven more by entrenching UK commercial interests than the geopolitical Cold War duel with the Soviet Union, declassified files from the late 1960s show.

British officials consistently emphasised the importance of dominating the airwaves in order to control the region’s energy resources and keep favoured regimes in power.

The BBC recently revealed that the UK government persuaded the Reuters news agency to set up a news wire in the Middle East in the late 1960s, funded surreptitiously through the BBC itself. The state broadcaster claimed in its article the reason for the operation was to win a “propaganda battle with the Soviet Union”.

Through a shadowy Foreign Office division named the Information Research Department (IRD), and with the help of BBC executives, British officials developed sophisticated ways of “maintaining and extending our influence” through the “non-military” method of “information services” – that went beyond Cold War rivalry with the Kremlin in the region.

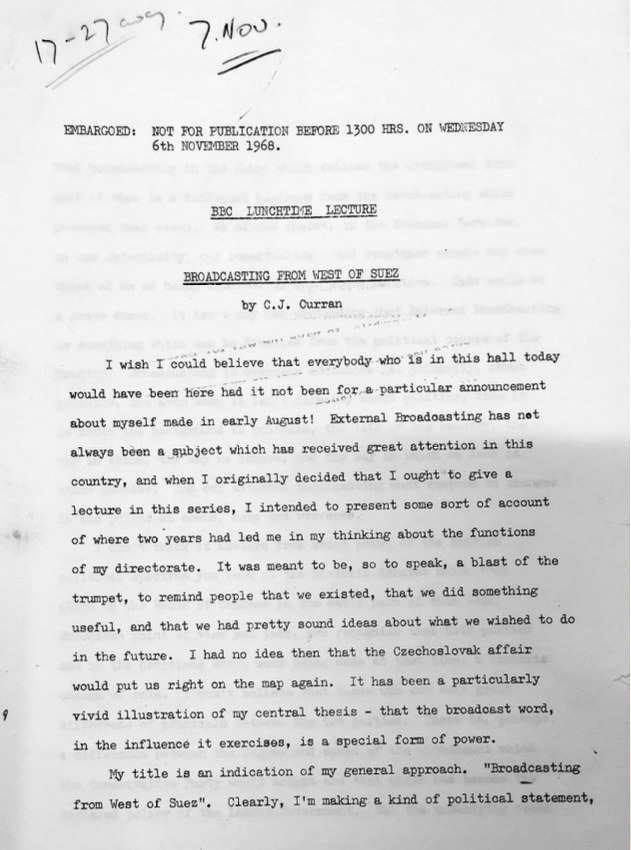

The BBC’s Overseas Services chief, Sir Charles Curran, said in a speech to colleagues in November 1968 that the “instrument” for promoting the UK’s commercial interests was “the dissemination of information in order to promote stability in our trading areas”.

He added, “It is, as it always has been, the interest of Britain that there should be stability in as many parts of the world as possible, so that we may carry on trade without a hindrance.”

“The means of achieving this have changed over the years. It used to be the East India Company or the Hudson Bay Company. Later it was the Imperial Forces. These have gone. I believe that the requirement is the same, but the instrument has changed.”

‘Large financial interests’

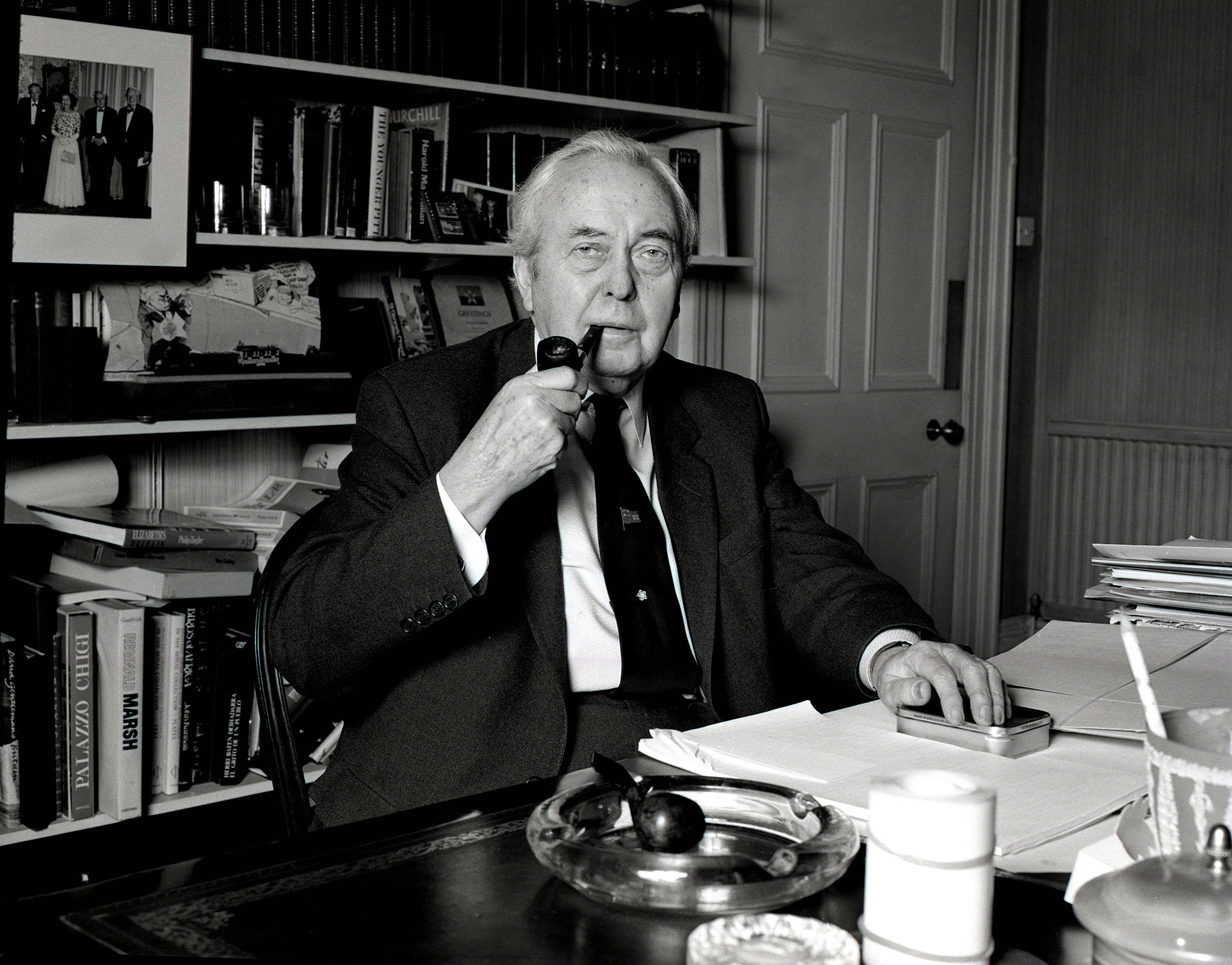

The desire to expand British “information” services in the Middle East came at a time when some UK officials had concerns about the decision of Harold Wilson’s Labour government to withdraw military forces from “East of Suez”, particularly the Gulf states whose rulers were heavily dependent on Whitehall’s support.

In October 1968, British “information officer” Edward Henderson wrote from the UK residency in Bahrain that “we are now worried about… our withdrawal from an area in which we have such large financial interests”.

He added, “it is of utmost importance that a good Arabic teleprinter service to this area is kept up. Its inception here had been the biggest gain in the information field for years.”

The UK had spent £1-million building an extended runway at Bahrain airport “in order to ensure its survival as a communications centre”. A British official also advised the country’s dictator to “impose visa restrictions for British journalists” to stop information getting out that might “disturb internal security”. He added: “Nothing should disturb the peace in Bahrain”.

In summing up the secret negotiations between the BBC and Reuters, the former head of the BBC’s Eastern Service, Gordon Waterfield, wrote that “Although there is a pressing need to save money, [the British government] will, presumably, consider that it is especially important at this moment that areas such as the Persian Gulf, Saudi Arabia, South Arabia, and Libya should receive a good service in Arabic.”

The negotiations hit a snag in late 1968, however, when the Foreign Office learned of Reuters’ plans to operate out of Cairo, and to provide fewer hours of news service each day in Arabic.

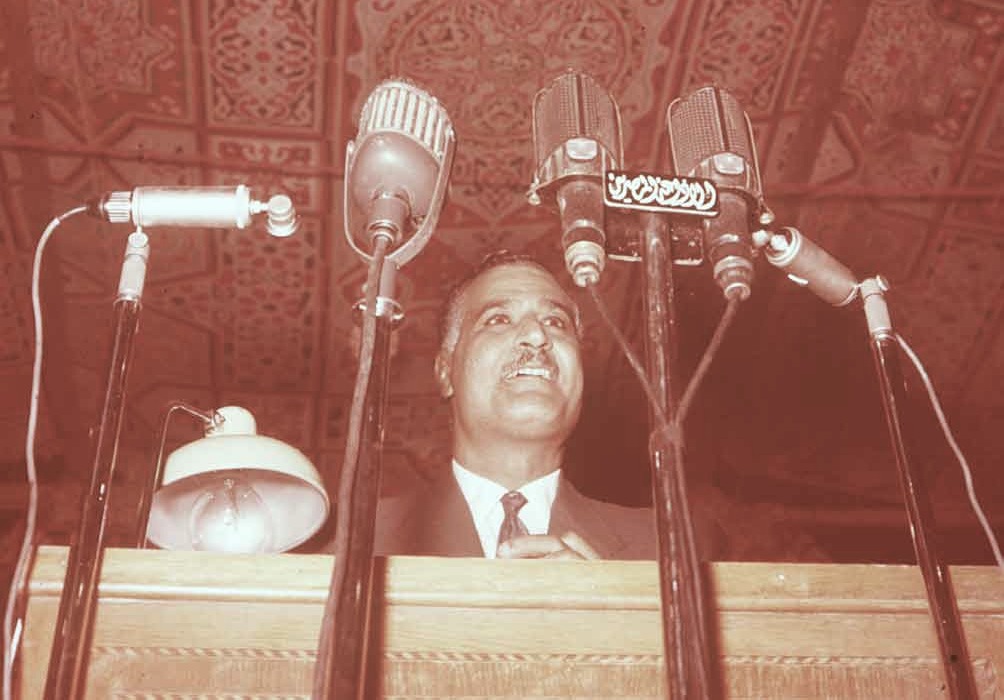

With Egypt then ruled by Gamal Abdel Nasser, the UK’s bête noire in the Middle East whom it had sought to overthrow, British officials worried that, in Cairo, Reuters would be “vulnerable to covert interference, censorship and interruption”.

Officials viewed Nasser as a unique threat to British interests given his possession of a powerful radio transmitter, which he used to encourage pan-Arab unity across the region. One information officer protested that Britain’s key regional assets would be most affected: “It is in just these areas where [the UK government] seeks political dividends from the service (ie the Gulf) that objection to a service emanating from Cairo is likely to come.”

Investments in the Gulf

The UK’s alliance with the US was also a factor in British planning. The UK ambassador in Washington, Sir Patrick Dean, was concerned that “our special relationship depended on our assets in areas where we had a particular entrée viz the Middle East and South-East Asia. Were they to be aware of the fact that we were putting our news services under Egyptian control, I think they would be disturbed.”

One British official hoped that, “since we have protected vast US investments in the Gulf area for so long, I would not exclude the possibility of [the US] being ready to help us finance a News Agency/Broadcasting Service in the Gulf”.

Information officer RA Burroughs, meanwhile, thought the burden should be shifted onto the “oil-rich Sheikhs to build a really powerful radio transmitter” in the Gulf “where the vast majority of our interests lie”, and for which “a fat contract” should be granted.

An agreement with Reuters was ultimately reached in early 1969. In exchange for “concealed” UK government support funnelled “surreptitiously via the BBC”, the Foreign Office expected Reuters to be “amenable to background guidance in London”. This influence “would flow, at the top level, from Reuters’ willingness to consult and listen to views expressed on the results of its work”.

It was not until January 2020 that the BBC eventually informed the public about its secret deal, and even then it sanitised the internal discussions between UK officials by claiming that “British diplomats in the Middle East… wanted ‘an objective and accurate service of high quality’ to combat what they described as ‘calculated fabrications’ from ‘slanted’ agencies”.

In fact, a fuller reading of the declassified files shows that British “information” policy in the Middle East centred on maintaining internal “stability” in the Gulf states and that Britain mainly sought to retain access to key resources upon which its global power relied. The struggle against “Soviet propaganda” is barely mentioned in the files.

Long-standing policy

The British government had used “information” policy to promote its interests for some time. In 1955, foreign secretary Harold Macmillan stated in relation to the Middle East: “We need to promote internal political stability and in particular to influence individuals so that public opinion does not become so hostile to our oil companies that their commercial operation [sic] becomes impossible.”

Similar concerns were voiced four years before, when the UK was opposing Iranian attempts to nationalise its oil industry, led by democratically-elected prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh.

A Foreign Office official noted in March 1951 that “it would be useful to inspire the BBC’s Persian Service at this present stage in the oil question”. The official suggested several lines of argument to be followed by the BBC, “including a focus on financial losses, the harm to Iranian reputation internationally and the adverse effects on the industry as a whole”.

Three days later, these very points were broadcast in Iran by the BBC’s Persian Service.

And in 1978, when the British government was losing confidence in the shah’s ability to hold on to power and BBC reporting became more critical of him, British ambassador to Iran Anthony Parsons secretly requested that the US pressure prime minister James Callaghan to pull the BBC back into line.

Another secret US file published by WikiLeaks shows that British officials took the US ambassador “aside” in November 1978 “to offer assurances that they are keeping an eagle-eye on BBC Persian language service to ensure absolute accuracy”.

“After the usual caveats about BBC independence”, one British official “volunteered” to the US ambassador “that he takes our point about accuracy seriously”.