It can also be revealed that this programme, which is embedded in the UK’s Ministry of Defence (MOD) but paid for by the Saudi regime, employs ten times more people than the British government publicly admits, raising questions about ministers misleading the parliament in Westminster.

The Saudi Arabia National Guard Communications Project (known as Sangcom) has operated since 1978, when the British government signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the authorities in Riyadh. The project provides military communications equipment to the Saudi Arabian National Guard (SANG) but the MOU, which is itself secret, stipulates complete secrecy on the budget.

In July this year, however, the MOD advertised for the position of a Sangcom project manager based in Riyadh. The job was open only to male applicants and the advert stated: “The UK MOD SANGCOM Project Team is responsible for the delivery of a £2bn programme to modernise the Saudi Arabian National Guard’s communications network.”

This is the MOD’s first public acknowledgement of the size of Sangcom’s budget in its 40-year history and such a casual mistake is likely to infuriate its Saudi counterparts. As recently as March 2019, Labour MP Catherine West asked a parliamentary question about the programme’s budget and was told that it is “confidential to the two governments”.

It is understood that this £2-billion budget runs for 10 years and was agreed in February 2010. This new phase of the Sangcom project is 15 times larger than the previous agreement, worth £124-million and signed in 2004.

The MOD spends £1.4-billion per year on its own IT and telecommunications systems.

An MOD spokesperson told us: “Information in this job advert was uploaded in error and it was subsequently taken down,” adding, “the budget is confidential to the two governments.”

But, in a further sign of unusually lax information management, the job advert, while being taken down on some sites after the MOD was alerted, is still available on the internet. In addition, Sangcom’s financial controller states on the social network LinkedIn that he is “responsible for a budget of circa £1.6B”.

The White Army

Also known as the White Army, the Saudi Arabian National Guard comprises about 130,000 troops and acts as an internal security force separate from the regular Saudi army. Drawn from tribes loyal to the ruling Saud clan, the SANG’s essential task is to protect the royal family from a coup.

The Sangcom project, alongside Britain’s long-standing military training of the SANG, clearly implicates the UK in the defence of the House of Saud, along with the US, which is also training and arming it.

The SANG has also been involved in the Saudi-led war in Yemen, which has created the world’s largest humanitarian disaster, with 24 million people — nearly 80% of the population — needing assistance and protection.

In April 2015, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman ordered the SANG to join the Yemen campaign, which until then had been the preserve of the Saudi air force and the regular army. In 2018, a classified French intelligence report noted that two SANG brigades — about 25,000 men — were deployed along the border with Yemen. Major General Frank Muth of the US military also revealed that a SANG brigade, returning from fighting at the border with Yemen, had 19 of its light armoured vehicles “shot up pretty badly”.

Earlier this year, another US military official, Colonel Kevin Lambert, manager of the US’s own SANG modernisation programme, confirmed that the SANG was “executing combat operations in the Yemen conflict”.

The UK’s support for the SANG is another aspect of its involvement in the Yemen war, which continues even after the government lost a court case concluding that weapons sales to Saudi Arabia were unlawful.

Secret programme

Shrouded in secrecy, almost no information on Sangcom is available to the public or the British parliament. In response to another parliamentary question, in 2014, the government said only: “The function of the Sangcom Project is to support the United Kingdom’s commitment to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by acquiring and supporting modern communications capabilities for the Saudi Arabian National Guard.”

We understand that the programme, which is commanded by a British army brigadier, also has a training element, instructing SANG officers to operate project equipment and technology.

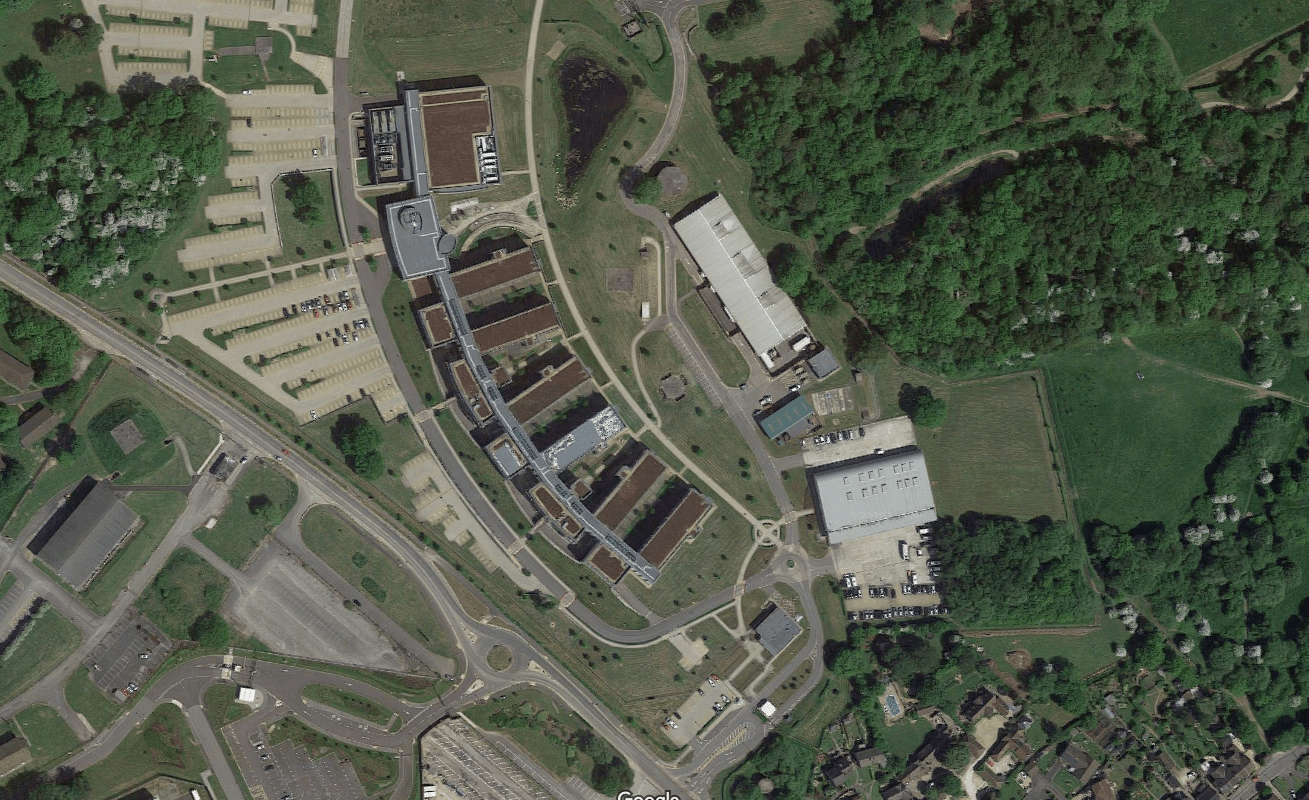

Sangcom is based in Riyadh, Jeddah and Dammam in Saudi Arabia and at the MOD establishment at Corsham, Wiltshire, in the UK – which is home to the military’s Joint Cyber Unit and headquarters of the 10th Signals Regiment, one of the military’s specialist telecommunications units.

The distinctive feature of Sangcom is that the Saudi regime pays the MOD to run the project. It is not clear if there is another military arrangement like this between two countries anywhere in the world.

“This level of institutional cooperation and support is symptomatic of the cosy and immoral political and military relationship between the Saudi regime and the UK government,” said Andrew Smith, spokesman for the Campaign Against the Arms Trade. “It is a relationship that is damaging to the UK, but has also helped to entrench the brutal Saudi regime and provide a figleaf of legitimacy for its authoritarian rule.”

Hundreds of employees

The true cost of the Sangcom project is likely to raise questions. But also of interest is the number of staff the programme employs. Sangcom has since 1994 been managed on behalf of the MOD by a British company called GPT Special Project Management Ltd, based in Stevenage, just north of London. It is now a subsidiary of aerospace company Airbus.

GPT’s managing director Andrew Forbes is a 25-year veteran of the British military’s Royal Corps of Signals while his predecessor, Simon Shadbolt, served for 26 years as a Royal Marines officer and is now “head of KSA [Kingdom of Saudi Arabia] Strategy” at Airbus’s defence and space division.

Company accounts show that GPT, whose sole project is Sangcom, employed 535 people in 2018 and has consistently employed more than 480 people since 2015. UK government ministers have consistently understated the size of the full Sangcom programme.

In March this year, parliamentary under-secretary of state for defence, Stuart Andrew, was asked in a written question how many civilian staff and military personnel based in the UK and Saudi Arabia “were employed on the Saudi Arabian National Guard Communications Project”. Andrew’s reply stated 76, of whom 74 were based in Saudi Arabia. He was echoing previous ministers’ answers to the effect that the programme employs only 50-60 people.

However, these figures refer only to Sangcom’s MOD team. No minister has ever mentioned the number of staff employed by GPT, which actually runs the Sangcom project.

Other ministers giving similar answers to parliament in recent years were Michael Fallon, then Defence Secretary, Mark Lancaster, the current Defence Minister, and former Defence Ministers Tobias Ellwood and Philip Dunne. Answers given by ministers in these cases were technically correct, being in response to questions asking how many Sangcom staff there were in the MOD specifically. But in failing to volunteer information on the size of MOD’s prime contractor for the project, ministers have obfuscated its real size.

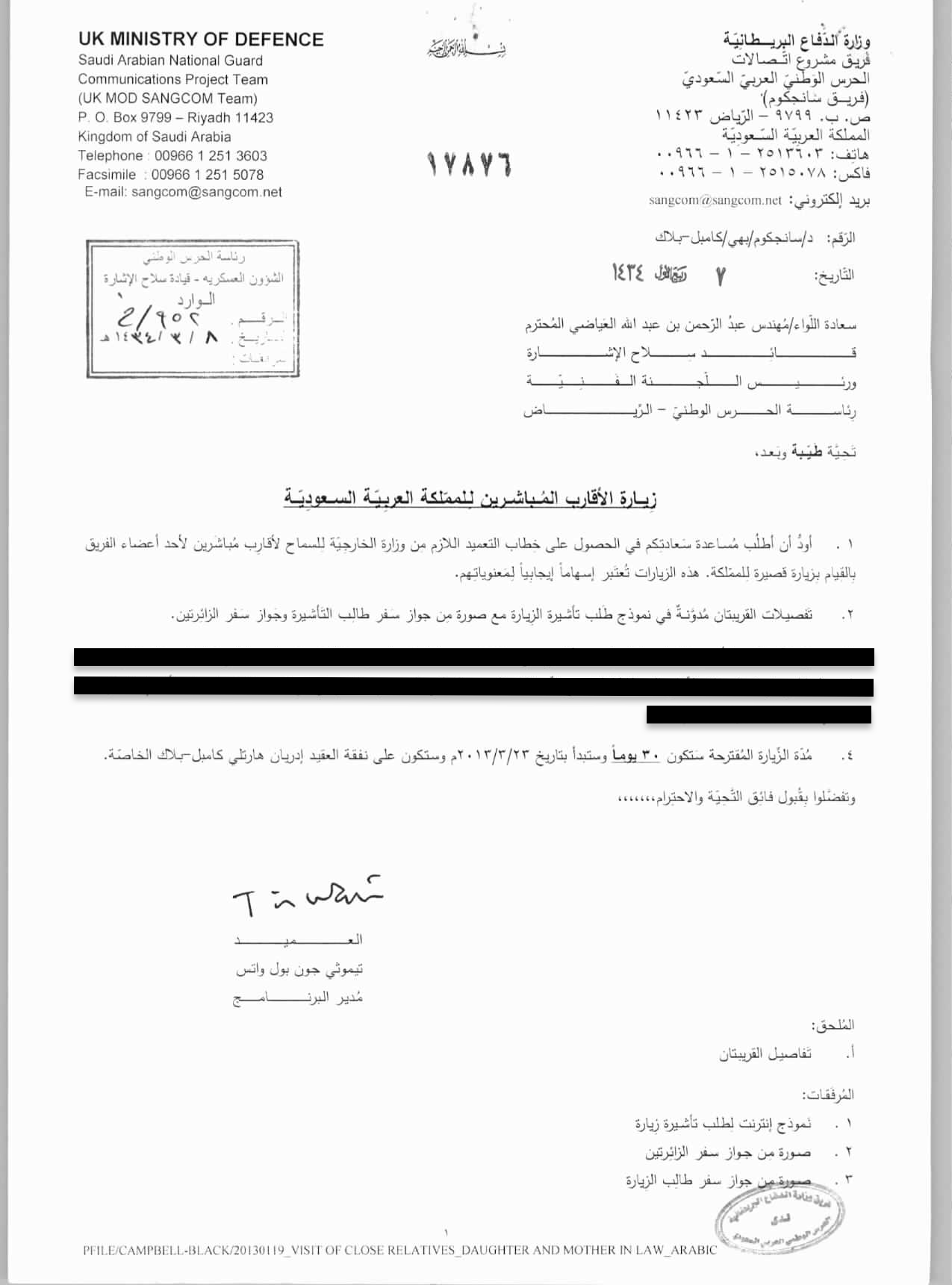

In reality, there is little distinction between GPT employees and MOD Sangcom advisers. They work alongside each other within the “MOD villa” at Kashm al Ayn, near the capital Riyadh, which also houses the SANG School of Signals, and within SANG regional command centres in western, central and eastern Saudi Arabia.

A sign of the closeness between GPT and the Saudi royal family is that the company long employed a Saudi princess as its director of human resources, probably reasoning this would further cement relations with the ruling family.

Ten times the number of staff

Sangcom now appears to be becoming even bigger. GPT is being closed down by its owner, Airbus, and the MOD has signed a new agreement with the giant US-based military and cybersecurity corporation KBR to run the Sangcom project. Although no information has been released by the UK government or KBR on this new contract, the latter has been advertising online to fill posts for the project in Saudi Arabia.

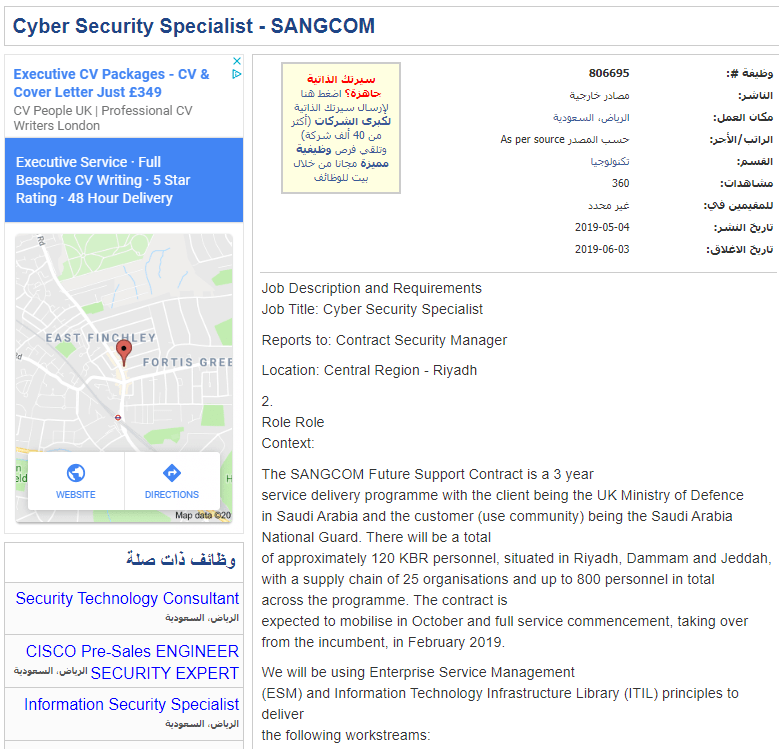

One advert, for a cybersecurity specialist based in Riyadh, reveals that the “Sangcom Future Support Contract” is “a three-year service delivery programme with the client being the UK Ministry of Defence in Saudi Arabia and the customer (use community) being the Saudi Arabia National Guard”.

It reveals there will be “up to 800 personnel in total across the programme” including about 120 KBR personnel in Riyadh, Dammam and Jeddah and a supply chain involving 25 organisations. This job advert notes that the role will interface with an MOD security officer as the principal point of contact as well as a KBR manager in Leatherhead, Surrey.

None of this information has been divulged by the UK government.

Shrouded in secrecy

Almost no information is in the public domain on what Sangcom does. Despite costing £2-billion and employing hundreds of staff, the programme is not mentioned on the websites of the British government, Airbus or KBR, while GPT has no website.

There have been six parliamentary questions asked by MPs on Sangcom in the past five years, all have elicited minimal responses from the government. The secrecy surrounding Sangcom is probably explained by the sensitive nature of a British military project supporting the Saudi ruling family.

However, it may also be explained by long-standing concerns about bribery.

Since 2012, GPT has been under investigation by the UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) following revelations by the Sangcom programme director at GPT, Ian Foxley, who claims to have evidence of multimillion-pound bribes paid to Saudi officials.

Foxley, a former army officer, alleges 16% of the costs of Sangcom contracts were disguised as “bought in services”, a euphemism for bribes, which could amount to £750m in such payments over the lifetime of the programme since 1978.

Foxley states that the GPT contracts must have been approved by someone senior in the MOD. Now writing a book on his revelations, Foxley told us that the MOD “must have known” about the bribes. “Around 50 people may have seen these documents over the years inside the Sangcom project team, from the brigadier downwards,” he said.

This would be consistent with a stream of arms contracts Britain has signed with Saudi Arabia since the 1960s, in which corruption has been a regular element. Such large payments to key Saudis are long believed to play a role in helping sustain the House of Saud in power.

Seven years on from opening the investigation, it is not clear if the SFO will be allowed to prosecute GPT, which could prove whether MOD officials approved illicit payments to Saudis.

There is also the possibility the government will act, as then Prime Minister Tony Blair did in 2006 over another SFO investigation into bribery concerning Saudi Arabia and BAE Systems, and stop the prosecution on spurious “national security” grounds.

Sangcom also raises the broader question for national security of having a foreign state deeply embedded inside the MOD, especially in a programme so secret that the British public and parliament know almost nothing about it.