Say ‘UDR’ to the vast majority of Britons and, despite the increasingly totemic status of ‘our boys’ in the military, eyebrows will universally raise.

Yet the Ulster Defence Regiment was active throughout most of the recent conflict in Ireland – the longest period of continuous duty of any British military unit.

Successive UK governments lavishly praised its courage and commitment to peace. There were regular visits by members of the royal family to barracks and parade grounds across Northern Ireland from Fermanagh to Belfast.

A recently-published book, however, reveals a quite different story.

UDR Declassified by Micheál Smith relies for hard evidence on declassified internal British memos, position papers and analysis, much of which were retrieved from the UK National Archives over the last two decades by the Pat Finucane Centre.

Successive governments in London, the book argues, fueled the conflict in Northern Ireland by policing and alienating one part of the community (those who are pro-Irish unity, mainly Catholic) while arming, training and providing intelligence information through the UDR to the other section of the community (those who are pro-union, mainly Protestant).

“Writers of books like this”, says Smith, “often get accused of re-writing history. But history is always rewritten whenever new evidence proves it wrong. This evidence allows us to narrow the permissible lies”.

‘A kind of monster’

The UDR was formed in April 1970, supposedly to replace the discredited “B-Specials”, a quasi-military force. All the UDR’s original seven battalions, however, were led by former B-Special county commandants.

Hardly surprising, then, that the UDR is described by French political scientist, Anne Mandeville, as “a kind of monster”.

While it was supposedly an arm of the British state, she says, in reality it was “deeply in solidarity with the Protestant community”.

Integrated into the British Army, it was also divided from it “organically, geographically and by its specificity”, a toxic recipe for any law-enforcement unit seeking cross-community support.

For many Catholics, the slogan ‘UDR by Day: UVF by Night’ was a lived reality, referring to the oldest loyalist paramilitary group in the conflict, the Ulster Volunteer Force.

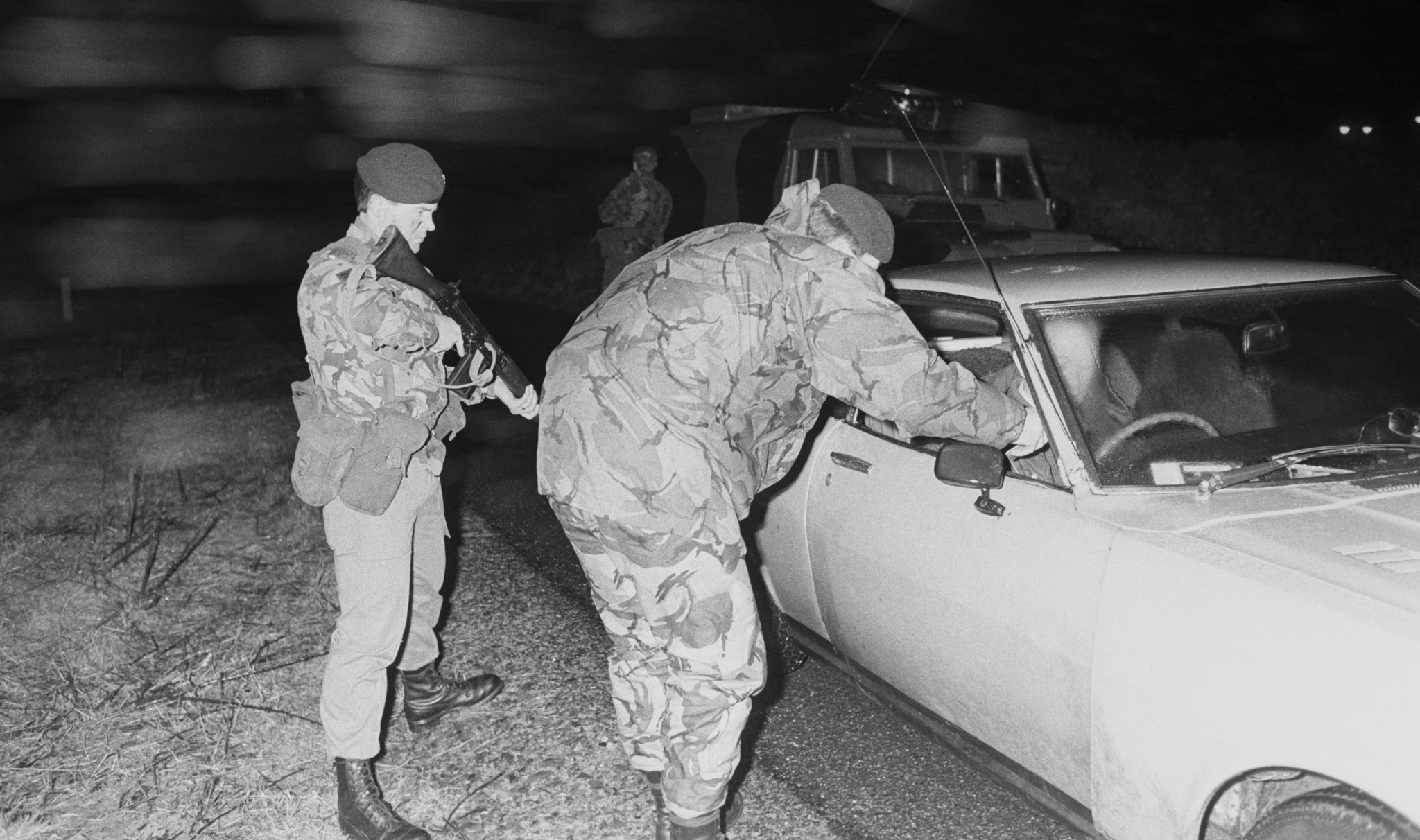

Stories abound of people stopped on the roadside in the dead of night – or on the way home from church or Gaelic sporting fixtures – to be insolently abused or worse.

The one-time leader of the moderate nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and Nobel peace prize winner, John Hume, described the regiment as a “group of Rangers supporters put in uniforms, supplied with weapons and given the job of policing the area where Celtic supporters live”.

More officially, a 1984 briefing document prepared for the then Northern Ireland Secretary, Douglas Hurd, concluded: “The regiment is mistrusted, even hated, in much of the Catholic community, and by many Catholic politicians”.

It added: “More significantly, it is not held in the highest regard by the RUC itself (including the Chief Constable …) even amongst regular soldiers it is not universally popular.”

The UDR was also seen as an impediment to peace. In 1986 a Foreign Office official noted in a memo to a Ministry of Defence colleague that: “For all its courage and dedication (which I certainly do not underestimate), and despite its incorporation into the British Army, the UDR is an inescapably sectarian body and an obstacle to reconciliation between the two communities in Northern Ireland.”

Counter-insurgency

Smith, while pulling no punches, freely concedes not every member of the regiment was motivated by sectarian hatred. Far from it, he says many of its members wished to end the conflict through patrolling, surveillance and lending their local knowledge to support the police, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).

The main thrust of this book, however, judges the UDR in its structural context, rising well above a day-by-day account of its sectarian and criminal failings. Instead it examines the regiment’s role as a key element of British colonial/post-colonial counter-insurgency strategy in Ireland.

That is not to say the UDR’s dubious record is overlooked. Smith points out that between 1985 and 1989, UDR members were twice as likely to commit a crime as the general public. The UDR crime rate was 10 times that for police officers in the RUC and about four times the British army rate.

The central problem, he says, is that London never viewed the problem in Northern Ireland as rooted in a demand for civil rights, equality and constitutional reform. Instead it blindly interpreted republican violence as a criminal conspiracy that must be crushed.

The book is full of examples where, rather than deal even-handedly with both communities, London concluded that armed republicanism was its only true enemy. Just three examples from the book suffice to show the malign out-workings of this policy.

Shockingly, it points out that the word “collusion” to describe covert collaboration between loyalist paramilitaries and state forces was first used as early in the conflict as September 1971 when a rifle was reported taken and “connivance” suspected.

Even more disturbing was the lack of police inquiries into “missing” weapons such as the “theft” of sub-machine gun serial number UF57A30490, taken from Glenanne UDR barracks in County Armagh, in May 1971.

This weapon was subsequently used to murder 11 people in 11 months, leaving four children orphaned and 19 fatherless.

Heavily infiltrated

London cannot say it was unaware of the dangers. In 1975, Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson and opposition leader Margaret Thatcher were informed by an official that: “The Army’s judgment [was that] the UDR were heavily infiltrated by extremist Protestants and that in a crisis situation they could not be relied on to be loyal”.

Stunning evidence, even earlier, of the UDR’s dangerous proclivities is provided in an internal British discussion document entitled ‘Subversion in the UDR’, written in August 1973.

“It seems likely”, says the document, “that a significant proportion (perhaps 5% – in some areas as high as 15%) of UDR soldiers will also be members of the UDA, Vanguard Service Corps, Orange Volunteers or UVF”, referring to loyalist paramilitary forces.

Yet, the document concludes, little should be done about this: “The discovery of members of para-military or extremist organisations in the UDR is not, and has not been, a major intelligence target” and the UDR remained “wide open to subversion and potential subversion”.

Moreover, the same document concludes that “some soldiers are undoubtedly leading double lives” and that “the UDR is the single best source of loyalist weapons and their only significant source of modern weapons”.

Rather amazingly, there is even doubt over the very legality of the UDR. A 1981 memo, only recently discovered in the archives, notes concerns amongst Ministry of Defence legal advisers as to whether UDR soldiers were legally ‘on duty’, as the formal call-out procedures had not been followed since the early 1970s.

As a result, officials were concerned about the legality of arrests, search operations and other actions.

Technically, it may yet be possible for people to challenge pre-1981 arrests by the UDR through the Criminal Cases Review Commission. Convictions of persons for failing to answer a question or for resisting arrest might also be called into question.

But the book’s central focus is what the UDR did while its soldiers were let loose on the populace, legally or otherwise.

Blame for this deplorable and deadly lack of action, Smith concludes, should not be laid at the door of individual UDR members but at those who devised a policy of using it as a counter-insurgency weapon for three decades and who continue to escape detection and accountability of any kind.

The price, he points out, was paid by the UDR’s many victims whose lives continue to be blighted by its existence and because of its shameful record.