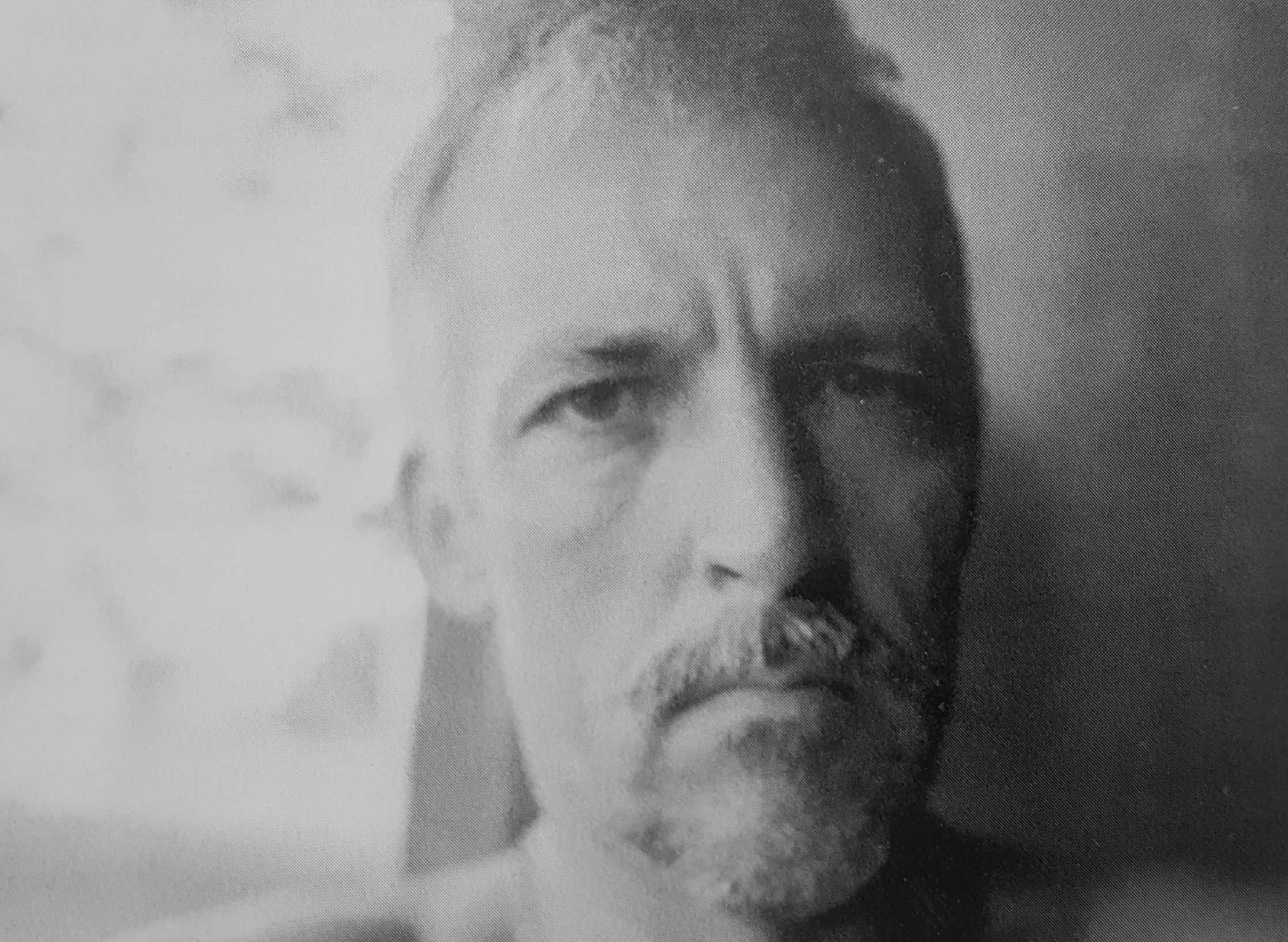

On a warm day in late spring 2018, a sleepy village in the English countryside was about to be disturbed by my team of investigative journalists. We were poised to interview Lieutenant Colonel Brian Baty, a reclusive former mercenary who we had tracked down to the village of Kings Pyon, a stone’s throw from the Special Air Service (SAS) base at Credenhill, Herefordshire.

His house was easily distinguished by a towering flagpole with a Union Jack fluttering on the front lawn, and a car with his personalised number plate parked on the driveway. My two colleagues started filming as I approached his front door and began to knock. At first there was no response, until an upstairs window swung open.

“Hello”, I called out as Baty, a well-built man in his eighties, appeared. “Yes and you can bugger off!”, he shouted down at me, before I had a chance to introduce myself. “Are you Lieutenant Colonel Baty?” I countered, trying to sound calm. “You can bugger off,” he repeated, irate.

Keenie Meenie [Trailer] from Yardstick Films on Vimeo.

I persisted and tried to question him about his time working for a notorious British mercenary company, Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), about which I had written to him previously and received no response. “These are very serious allegations sir… You’re being linked to war crimes in Sri Lanka,” I reminded him. “Bugger off my land, get out!” Baty shrieked back.

As Baty withdrew from the window muttering abuse at me, I asked: “Do you deny that KMS was involved in war crimes in Sri Lanka, under your watch?” There was no response. Baty could not deny it, he could only hope the issue would go away. Instead, it would follow him to the grave.

British army career: Imperial trooper in Malaysia, Oman and Yemen

Brian Richard Mark Baty was born in south London in 1933. He left school at 14 and joined the British Army’s Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, a notoriously tough Scottish infantry regiment, in 1951.

He was initially posted to British Hong Kong, but Baty’s career would quickly see him become a sought-after expert in the art of repressing anti-colonial struggles and national liberation movements, which were challenging British rule around the world.

Baty passed the army’s special forces selection test in 1956 on his third attempt and joined D Squadron, a major operational unit in the 22nd SAS Regiment. He was deployed as a signaller and interpreter to Malaya, a British colony (now called Malaysia) where Maoist insurgents were fighting for independence.

Baty serving in Malaya. (Credit: British Army)

In order to deprive the insurgents of food and support from the civilian population, British forces in Malaya forcibly resettled over half a million people into “new villages” that were ringed with barbed wire.

The policy, which would become a model for America’s “strategic hamlets” strategy in Vietnam, was brutally effective. By 1958, the “Malayan Emergency” had been sufficiently subdued for Baty’s squadron to be redeployed to the next colonial flashpoint: Oman.

Sultan Taimur, a British client ruler, was facing internal rebellion against his authoritarian rule in Oman. The Royal Air Force was propping up the Sultan by strafing date gardens to “inconvenience” farmers, as well as bombing wells in rebellious villages, a tactic later described as “denial of water supply to selected villages by air action”.

However, this was not enough to keep Taimur in power and elite ground troops from the SAS were also required. In 1959, following reconnaissance by British Army counter-insurgency expert Frank Kitson, Baty took part in a raid on Jebel Akhdar (“Green Mountain”) in which they routed the rebel stronghold near to Oman’s capital.

After Oman, Baty returned to England for three years before rejoining the Argylls in 1962 and moving with his family to Singapore, which was used by the British military as a base for continuing operations in Malaysia. In 1964, as a sergeant, Baty won the Military Medal for his “aggressive action” while fighting Indonesian forces in Sarawak, Malaysia.

The following year, Baty was promoted to become an officer in the British army and would play an increasingly important role in suppressing anti-imperial struggles. The next flash point came in 1967 in Aden (now part of Yemen), a British protectorate where an insurgent National Liberation Front (NLF) was demanding independence.

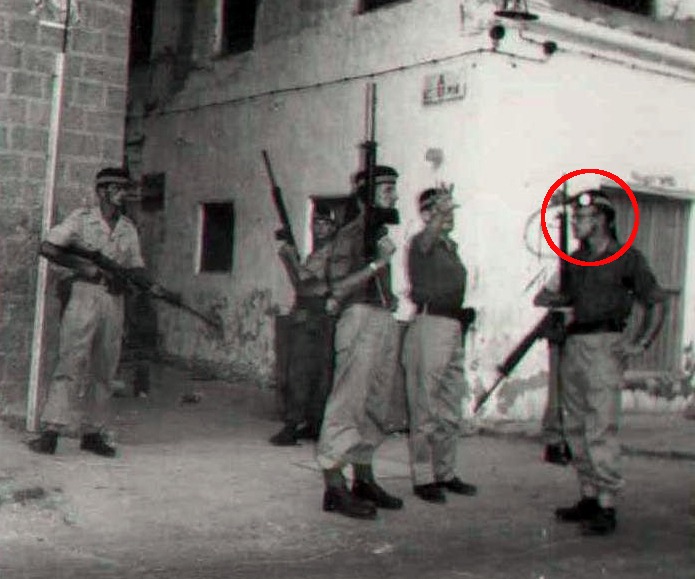

Baty (R) serving with ‘Mad Mitch’ (hand raised) in Aden. (Credit: British Army)

Baty served in Aden as the intelligence officer for the Argyll’s 1st Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Colin Mitchell, who was known as “Mad Mitch” for his notorious brutal stance toward the local population.

For his part, Baty was nicknamed “The Baron”, although it is not known why. NLF prisoners were reportedly tortured, but significant parts of the British archive from this episode have been destroyed. What is certain, from newsreel footage, is that unarmed Yemenis were physically assaulted by the Argylls.

Elite warrior in Oman and Northern Ireland

After Aden, Baty rejoined the SAS in 1971 and returned to neighbouring Oman, where he spent four years suppressing left-wing revolutionaries who were challenging Sultan Taimour’s repressive successor, Qaboos.

In April 1976, with the Omani revolutionaries mostly defeated and resistance to British rule in Northern Ireland escalating, Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson sent the SAS D Squadron to the IRA stronghold of South Armagh. By then, Baty had risen to the rank of Major and was the squadron’s commander.

With power came responsibility: When one of his men killed IRA prisoner Peter Cleary, Baty had to observe a subsequent police interview in which his unit was briefly investigated. The British army said Cleary was shot while trying to escape, but Cleary’s family claim he was killed in cold blood.

Baty’s tour became even more controversial when eight of his men were arrested by the Republic of Ireland’s Gardai police after they illegally crossed the border while heavily armed. Baty had to give evidence at a high profile court hearing in Dublin, where he denied his men were involved in clandestine cross-border operations and claimed the British army’s best soldiers had made a “map reading error”.

The embarrassing incident did not harm Baty’s career and he was mentioned in the military’s dispatches for his “distinguished service in Northern Ireland”. The SAS then put Baty in charge of its prestigious training wing and tasked him with reorganising its entire selection process from 1977 to 1979.

For his efforts, Baty won praise from SAS director General John Foley who was impressed by his “large planning ability, enormous powers of persuasion and tremendous talent as a trainer”.

The experience meant that in 1979, aged 46, Baty was put in charge of training men and women for undercover surveillance operations in Northern Ireland, which Foley described as a “most demanding post” that “would have caused younger men to flinch”.

Baty spent the last five years of his British army career trusted with a particularly sensitive assignment. He trained undercover soldiers at Pontrilas, a secretive base near to the main SAS barracks in Hereford. It is believed that his students went on to serve in the covert 14th Intelligence Company, a plain-clothed military unit that watched the IRA.

Foley praised Baty’s tenure in charge of Pontrilas, claiming: “Without his brilliant guidance, determined leadership and flair as a trainer, the effectiveness of surveillance operations would have been greatly reduced.” Foley recommended Baty for an MBE honour, a move which was supported by the Queen’s aide-de-camp, General Frank Kitson.

After 33 years of service, Baty left the British army in October 1984, aged 51, as a Lieutenant Colonel. He had risen impressively through the ranks, however he had made plenty of enemies. On Christmas Eve 1984 — just two months after he retired — the Special Branch of the British police arrested Peter Jordan, an Irish Republican sympathiser who had been plotting to blow up Baty.

Baty’s secret dirty war in Sri Lanka

Amid this turbulence, and perhaps because of it, Baty left the country. He began working for one of Britain’s most powerful private armies, Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), which is thought to be named after Arabic or Swahili slang for undercover activities.

Although the Telegraph newspaper compressed this part of Baty’s career to a single line in their glowing obituary of him, it was one of the darkest episodes in the violent world of British mercenaries.

KMS was run by well connected ex-SAS commanders who were paid handsomely to run the Sultan of Oman’s special forces, as well as helping US marine colonel Oliver North to overthrow a democratically elected left-wing government in Nicaragua.

Baty’s decades of counter-insurgency experience in Ireland, Oman, Yemen and Malaysia made him the prime candidate to lead a KMS team on another of the company’s major contracts.

Sri Lanka’s ruling Sinhalese majority urgently needed military support from KMS to suppress an armed separatist movement among its marginalised Tamil minority. Thatcher’s government had refused to intervene directly, fearing it might sour UK trade deals with India, which initially supported the Tamils.

One of Thatcher’s special advisers had suggested that “this venture might be privatised” and soon after, KMS began its work in Sri Lanka in January 1984. Their first task had been to set up and train a Sri Lankan police commando unit, the Special Task Force (STF) at a military academy south of Colombo in Katukurunda, that was modelled on the SAS base in Herefordshire.

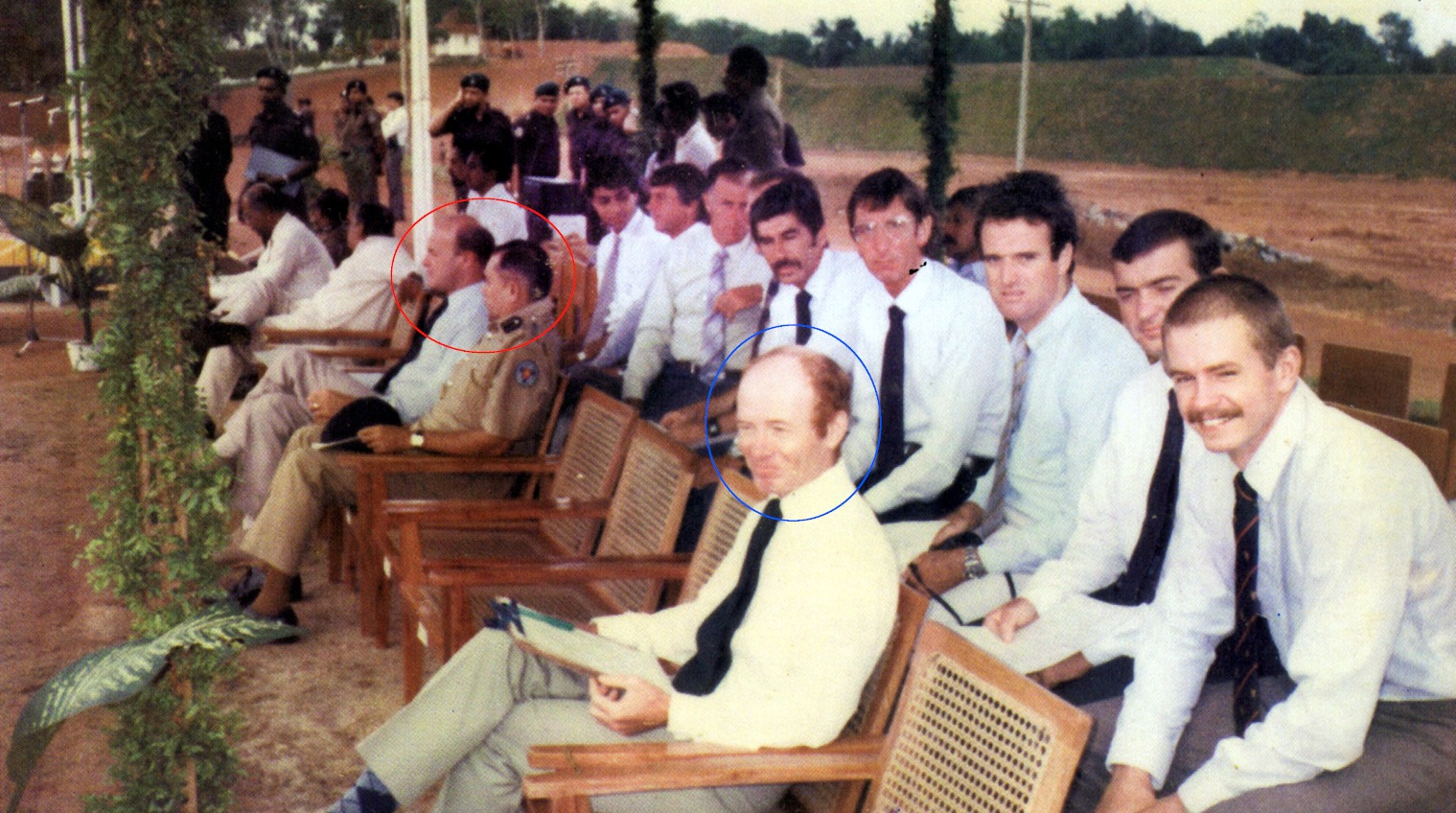

KMS men at the STF training academy in Katukurunda around 1985. Baty appears to be seated next to STF commandant Zerni Wijesuriya (red circle) and chief instructor Malcolm ‘Ginger’ Rees appears in the foreground (blue circle). (Credit: Sri Lankan police)

In September 1984, the STF was responsible for a massacre of up to 18 Tamil civilians in Point Pedro, and the unit only became more murderous the longer the KMS training continued.

By January 1985, Baty had started working for KMS from a base in the Sri Lankan capital of Colombo, where he used the alias Ken Whyte. Local Sri Lankan security chiefs told my team that they believed this “nom de guerre” would hide Baty’s whereabouts from the IRA.

Owing to his senior position at the head of the KMS team, Baty was installed in an office next to Sri Lanka’s National Security Minister Lalith Athulathmudali and had “direct access” to this leading politician.

Baty’s arrival, with his considerable experience of training SAS recruits, allowed KMS to expand its footprint in Sri Lanka and begin training a new army commando unit, in addition to the police STF. By March 1985, Baty appears to have been “acting effectively as the Director of Military Operations of the Sri Lankan High Command,” according to a declassified UK government telegram.

This level of responsibility is significant because around April 1985, the KMS-trained STF became implicated in atrocities along Sri Lanka’s west coast at Mannar, where a local citizens committee accused the unit of looting and rape.

Crucially, they noted that the STF was operating in unmarked cars and wearing plain clothes. This description suggests that elements of the police commando unit were operating undercover, as Baty had trained scores of British troops to do at Pontrilas before he joined KMS.

Many of these details about Baty’s time in Sri Lanka were recorded by the defence attaché at the British High Commission, Lt Col Richard Holworthy. The pair held “regular discreet meetings” to keep the UK Foreign Office “completely up-to-date on what KMS is doing”. These meetings were minuted afterwards by Holworthy, whom I have interviewed, and many of the documents he wrote are available to view at the UK National Archives.

Working against peace

By mid-1985, President Junius Richard Jayewardene had grown disappointed at the British mercenaries and commented privately that he “had hoped that the KMS training would have been more successful than it has been”. Jayewardene was forced to engage in peace talks with Tamil militant groups and embark on a ceasefire in June 1985, recognising that his British-backed ground troops were insufficient.

However, Baty was scathing of the ceasefire, complaining that it had “produced inertia throughout the army” and said the military was “putting too much faith” in the peace talks. KMS gave detailed advice to the Sri Lankan security forces on planning operations should the ceasefire collapse.

Baty carried on working with the security forces throughout the summer ceasefire of 1985. KMS reviewed the Sri Lankan military’s command structure and provided two former British special forces warrant officers: one as an operations room adviser and one as a psychological operations adviser.

This led a British diplomat in Sri Lanka to comment that KMS “have been drawn yet further into direct control of and participation in operations”. KMS began hiring British, Rhodesian and American aviators to fly Sri Lankan air force Bell Huey 212 helicopters.

Sri Lankan air force Bell 212 helicopters of the type flown by KMS pilots (Credit: Rehman Abubakr, creative commons)

The pilots were paid and controlled by KMS Ltd “through a front company in the West Indies”, probably in the Cayman Islands. The move would give the Sinhalese-side air superiority over the Tamils who had no air force of their own.

On 17 August 1985, the Tamil delegation walked away from the peace-talks, disturbed by the “genocidal intent of the Sri Lankan State” and accusing the Sri Lankan armed forces of “running amok” and killing Tamil children during the negotiations.

Piramanthanaru and Lake Road massacres

With the ceasefire in tatters, KMS was in a strong position to help the Sinhalese side win the next stage of the war. The company had dozens of personnel in Sri Lanka, led by Brian Baty, with a liaison officer assigned to the Joint Operations Command, the apex of Sri Lanka’s military decision-making.

Baty’s pilots embarked on operations to take territory from the Tamils in the north of the country. On 2 October 1985, a KMS pilot flew scores of Sri Lankan troops into the village of Piramanthanaru. As the pilot watched, soldiers rounded up and executed 16 male civilians, aged between 17 and 33. Homes and crops were also destroyed, according to an investigation by Tamil human rights expert Dr N Malathy.

On 13 November 1985, a land mine exploded on Lake Road in Batticaloa, seriously injuring five STF men. The STF then opened fire and nine Tamil civilians were killed. The STF later told investigators they had acted in self-defence. However, a Tamil eye witness claims that after the explosion he saw the STF walk five people down a road at gunpoint before executing them.

Their post-mortem reports show six of the deceased Tamils were shot from the back. Independent investigators said the STF’s version of events was “extremely improbable” and “far from convincing”. The dead included 18-year-old student Manojkumar Pirathapan.

Despite KMS and its partners being embroiled in war crimes, by December 1985, Baty was able to enjoy a private dinner with Jayewardene. The company now had 36 staff in Sri Lanka working with the airforce, STF, army and intelligence, although some staff were starting to feel the strain.

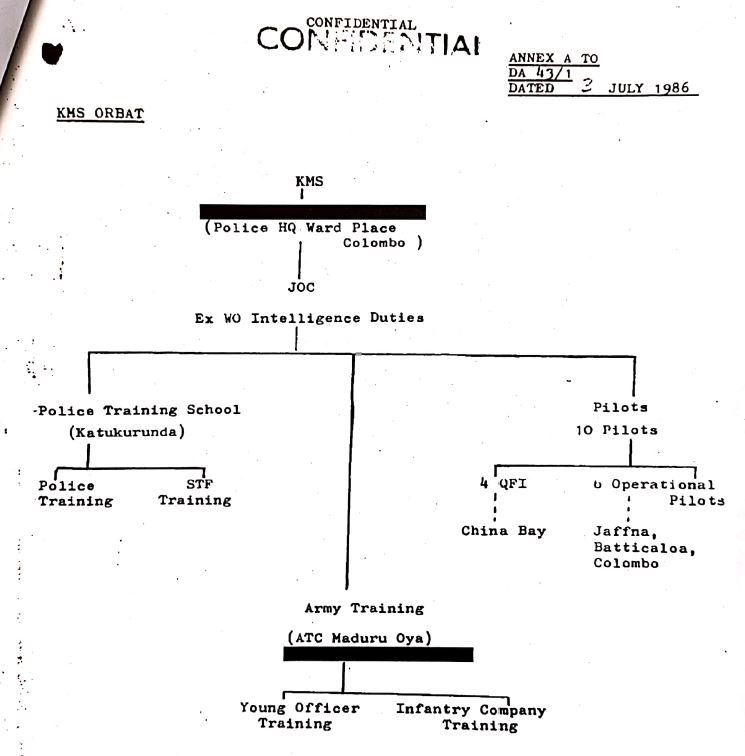

A KMS order of battle showing the company’s structure in Sri Lanka. (Credit: Richard Holworthy/UK Ministry of Defence)

On 17 December 1985, Malcolm “Ginger” Rees, another former member of the SAS D Squadron who had been involved in the illegal Irish border crossing, stopped working for KMS and stood down as chief instructor at the STF training academy having “gone rather odd,” according to a British diplomat.

By the end of December 1985, the leader of the main Tamil political party told a British Foreign Office minister that “whole villages” were being destroyed and British pilots were involved in aerial attacks on Tamil communities. The head of the UK Foreign Office’s South Asia Department noted: “We believe only KMS pilots are currently capable of flying armed helicopter assault operations in Sri Lanka.”

Tamil Holocaust

Baty’s secret war in Sri Lanka continued throughout 1986 and saw KMS complicity in war crimes escalate. The year had a bumpy start when a KMS pilot was shot down near Jaffna and had to be rescued, triggering a protest from three of the company’s aviators who said “they were not here to be shot at”.

Some respite came for Baty in February when, back in England, Peter Jordan was jailed for 14 years for plotting to assassinate him. Although Baty was now safe from Irish Republicanism, the troops he oversaw continued to massacre Tamils.

On 19 February 1986, between 40 and 60 Tamil civilians were shot dead in paddy fields near Lahugala in the eastern province. The British Foreign Office commented in a telegram: “It is becoming more certain that the Special Task Force were responsible for the massacre.” Although KMS assistance appeared to be leading to an increase in civilian casualties, the company decided to further deepen its role and begin training Sri Lankan army infantry officers.

KMS recruited a veteran of the SAS’ Iranian Embassy siege, Robin Horsfall to help with this task. However, Horsfall handed in his resignation to Baty in a matter of weeks, after hearing from Sri Lankan officers he had trained that their units were burning prisoners alive using rubber tyres as “necklaces”. In his memoirs, Horsfall later compared the situation facing the Tamils to the Holocaust and has told me he regards it as a genocide.

The author with KMS veteran Robin Horsfall. (Credit: Lou Macnamara/Yardstick Films)

Horsfall also expressed disgust at reports of civilian massacres from helicopters. Between August 1985 and May 1986, Tamil priests in Sri Lanka recorded more than 50 attacks by helicopters. The incidents included throwing acid from a helicopter, shooting dead a one-year-old child cradled in its mother’s arms, and firing on first responders as they tried to put a corpse into a van.

Although Horsfall’s exit was a blow for KMS, Baty soon found new recruits. These included Tim Smith, a former British army helicopter pilot. Captain Smith was deployed to Palaly, a Sri Lankan air base in the Tamil stronghold of Jaffna that was besieged by militants.

Smith later admitted in his memoirs how his Sinhalese helicopter crew were constantly killing civilians and that although Smith regarded his co-pilot, the lower ranking Flying Officer Namal Fernando, as a “bloodthirsty, murderous bastard”, he continued to fly on combat missions with him, despite realising that for the Sri Lankan air force “anything that moves following an attack was ‘in season’”.

In June 1986, when Smith attempted to distance himself from some of Fernando’s actions and refused to fly as the main pilot in the helicopter, Baty visited the Palaly air base and accused Smith of being disloyal to KMS.

This rebuke irritated Smith, and days later his anger expressed itself as he guided his helicopter crew through a sortie in which they fired 1,000 bullets at Tamil militants, killing 12. By the end of Smith’s first six-month tour, he estimated he had been “personally involved in the death of 152 Tigers”, as well as countless civilians.

KMS helicopter pilot Tim Smith. (Credit: Tim Smith)

While Smith worked with the Sri Lankan airforce and army, there were also mounting concerns about the conduct of the KMS-trained STF. In September 1986, the CIA compiled a secret report noting: “Although the STF shows greater discipline and professionalism than other security units, it is among the worst perpetrators of violence against Tamil civilians.”

American intelligence believed that although the STF’s superior combat performance was “due to its KMS training … a common STF tactic when fired upon while on patrol is to enter the nearest village and burn it to the ground.”

Prawn farm massacre

Baty’s contribution to war crimes in Sri Lanka would reach its gruesome climax in January 1987. By then, KMS had 38 highly-experienced men in Sri Lanka, including 17 training the STF. Baty remained permanently stationed in Colombo with a quartermaster who helped supply military equipment, and Baty had a colleague embedded on the Sri Lankan government’s Joint Operations Command.

On 27 January, the Sri Lankan army, STF and helicopter units moved in on the Kokkadicholai prawn farm in the eastern province. Local sources say 85 civilians were killed in the ensuing massacre, which is regarded as one of the worst of this stage of the war. Records show KMS pilots were operating in that area that month, although it is not known if they were flying in Kokkadicholai that day.

By this point in the conflict, the STF had received three years of training from KMS, and its operations had become far more lethal since its first massacre in September 1984 of around 18 civilians at Point Pedro.

This bloodshed occurred despite KMS employing Baty, who an SAS director claimed had “enormous powers of persuasion and tremendous talent as a trainer”. Either these talents had evaporated by the time Baty arrived in Sri Lanka, or he was content for the forces he trained to continue killing increasing numbers of civilians.

STF members at a firing range in Katukurunda in 2018. (Credit: Lou Macnamara/Yardstick Films)

He certainly faced no censure from the British government, who commented privately a week after the prawn farm massacre that it had “no problem with the training of ground forces” by KMS.

A very small number of KMS men did appear to object to the company’s role in Sri Lanka, and two of them refused to continue working for KMS around the time of the prawn farm massacre. Baty told British diplomats that one of the two men who had quit, Curry, was now mockingly referred to by his colleagues as “chicken curry”.

Final push

Baty appeared unaffected by the prawn farm massacre and allowed his men to train the army for a major offensive in Tamil stronghold Jaffna — “Operation Liberation” — planned for later in the spring of 1987.

KMS gave training for this offensive at command-level, battalion-level and in intelligence. British government officials were aware of this, but said that they were not concerned that KMS “may be involved backstage in the operations room in Colombo”.

On 26 May 1987, Operation Liberation was unleashed and napalm was used against Tamil civilians. The offensive was so intensive that neighbouring India feared its Tamil allies would be wiped out.

India began to air drop supplies to Tamil forces and by the end of July, Jayewardene had to allow an Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) to enter the north and east of Sri Lanka.

The IPKF pledged to disarm the Tamil factions, but the most autonomous group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), refused to accept either Indian or Sri Lankan authority and turned their guns on the Indian forces.

KMS pilots continued to fly Sri Lankan helicopters in support of the IPKF until 27 November 1987, during a four-month period in which around 1,000 Tamil civilians were killed by the IPKF, according to a study by the US army.

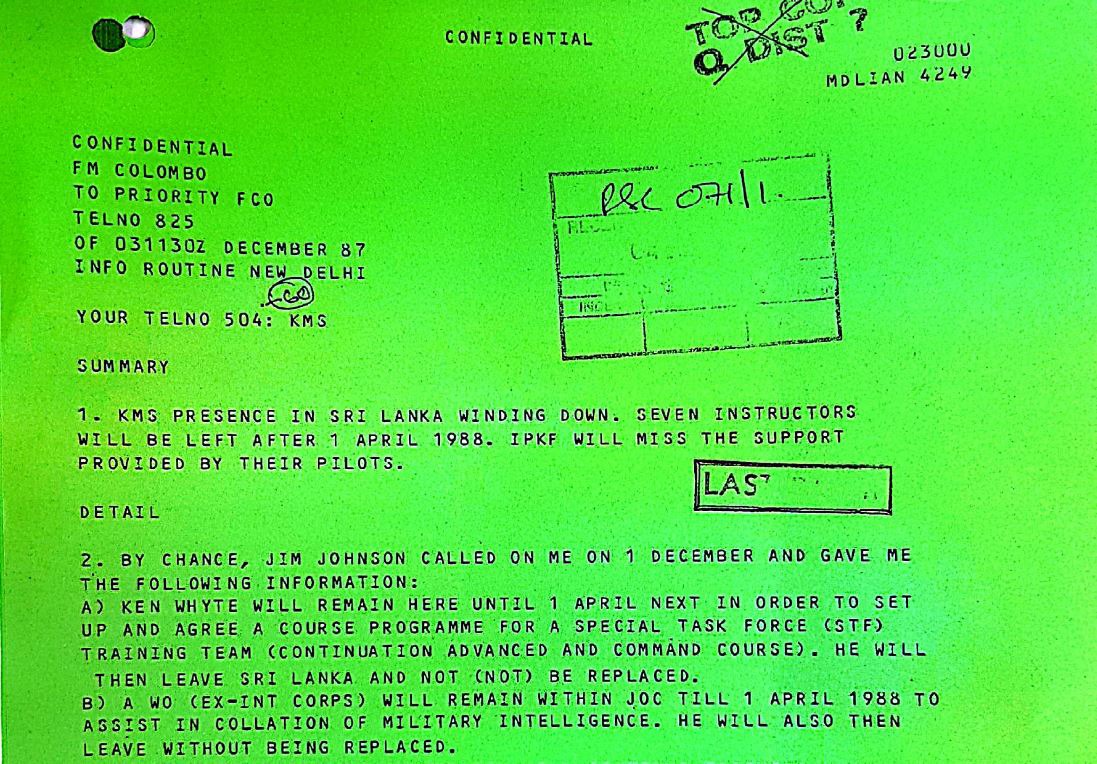

A confidential UK Foreign Office telegram outlines Baty’s exit plan from Sri Lanka (Credit: David Gladstone/UK Foreign Office)

The arrival of Indian forces in Sri Lanka had caused a Sinhalese uprising against Jayewardene in his southern heartlands by a group known as the JVP. But the STF proved just as willing to repress Sinhalese insurgents as it had been with the Tamils.

Britain’s then High Commissioner, David Gladstone, told me that the STF and other units “just went on killing and killing, until at a conservative estimate there were 60 odd thousand young Sinhalese men who were killed by the security forces”, by the end of the 1980s.

Declassified files show that Baty was scheduled to remain in Sri Lanka until April 1988 while he put in place an advanced command course at the STF training camp, which would eventually allow local Sinhalese personnel to take over the instructor roles from KMS. The company also maintained a former British army intelligence officer “within” the Sri Lankan government’s powerful Joint Operations Command, who was assisting them with the “collation of military intelligence”.

Cover up until the end

Although Baty had used the cover name Ken Whyte throughout his time in Sri Lanka, his role there was partially disclosed as far back as 1993 in a book by Stephen Dorril. However, there has never been a UK government investigation into Baty’s command level responsibility for war crimes in Sri Lanka — or even his position as an accessory.

Rather, there is a strong sense that the British state has sought to cover up the fact that one of its most loyal special forces commanders went on to be involved in such a dirty war. After I doorstepped Baty at his home in 2018, Horsfall received a call from a serving member of the SAS who tried to persuade him not to speak to me about KMS.

Of course, the special forces have no authority to deter former members from talking to journalists about their subsequent careers in the private security industry, and Horsfall refused to shut up. However, the official obfuscation has continued, and multiple British diplomatic files about KMS have been destroyed or are being withheld from journalists. The British government’s apparent attempt to cover-up for a private company is curious.

In January 2019, I wrote to the UK Foreign Office’s secretive archive team at Hanslope Park in Milton Keynes to warn them that their continued censorship of files about KMS meant the department “could be acting as an accessory to war criminals, by helping to shield the culpability of men like Brian Baty”. They ignored my concerns.

Despite years of official obstruction, in January 2020, I published my book, Keenie Meenie: The British Mercenaries Who Got Away With War Crimes, which laid bare the extent of Baty’s misdeeds in Sri Lanka. It caught the attention of the Daily Mail, who referred to the allegations against Baty by name in a review of my book in late-January.

Front cover of the author’s book.

Whether Baty read my book or that article is unclear, but he died soon after on 27 February 2020. His death was only announced publicly in April in a Telegraph obituary that made no mention of the controversy surrounding Baty’s time in Sri Lanka. The Telegraph appears to specialise in writing hagiography about KMS veterans – having previously published a eulogy about the company’s late chairman.

Days after Baty died, the Foreign Office’s South Asia Minister Lord Ahmad wrote to British Tamil community groups to say that my book detailed “war crimes allegedly committed by members of the firm Keenie Meenie Services against civilians in Sri Lanka” which were “very serious allegations”.

So serious in fact that Ahmad recommended the Tamil community raise them “with the War Crimes Unit of the Metropolitan Police”. The minister added: “I can assure you that the British Government will continue to press for truth, accountability and reconciliation in Sri Lanka.”

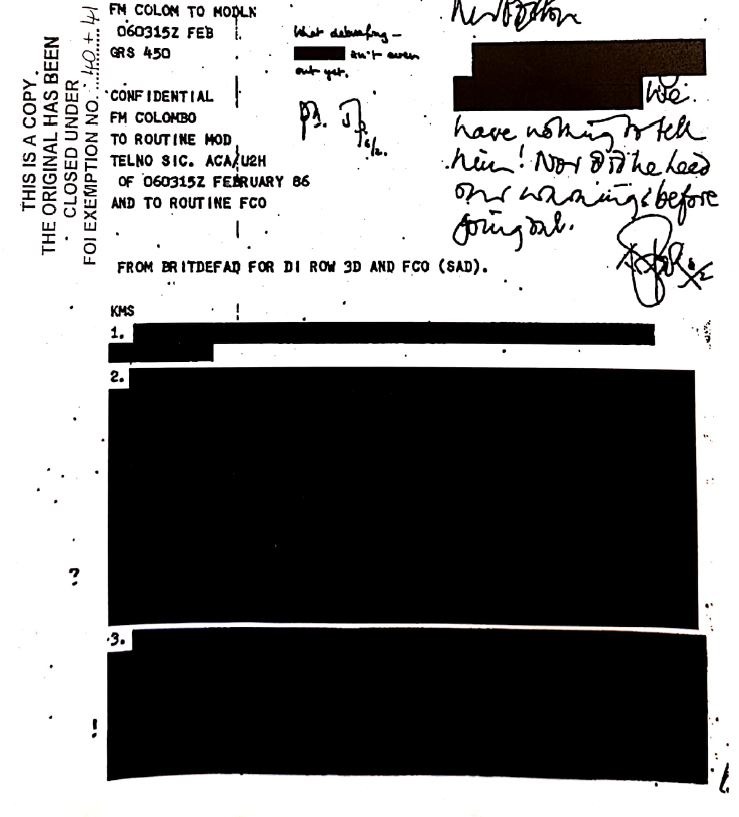

Despite this sympathetic rhetoric, in reality the Foreign Office continues to cover for Baty. A week before he died, they reluctantly released some more paperwork about KMS, but with heavy redactions – an entire page blacked out for instance. In these documents, they had also started to redact Baty’s alias from the paperwork, which previously they had been willing to publish.

A UK Foreign Office telegram about KMS from 6 February 1986 that was only released to the author 34 years later in a heavily redacted version on 13 February 2020 (Credit: UK Foreign Office)

The full truth about the extent of Baty’s dirty war in Sri Lanka is still to come out. I am appealing several freedom of information requests, although on 31 March, the Information Commissioner Elizabeth Denham CBE decided against further disclosure of a file from the start of 1985, when Baty began working for KMS.

Although Denham claimed to have “considered the complainant’s allegations to link the KMS employees and the massacres of the Tamil population by the Sri Lankan forces”, she ruled that there was “a stronger public interest to protect the ability of the UK to communicate with or about other countries in confidence”.

This extraordinary decision completely fails to take into account the pain caused by Baty and his colleagues to the Tamil community, and will be challenged in court at the Information Tribunal. If I lose my appeal, we will have to wait until 2046 for the file to be declassified.