The UK government is trying to insert a new clause into its highly controversial “Legacy Bill” on Northern Ireland which would remove the right to compensation for people illegally interned in the 1970s.

Claims are already in the legal pipeline over wrongful internment which would leave London with a multi-million-pound bill compensating 200 people jailed without the proper personal consideration of the Northern Ireland secretary, as required by law.

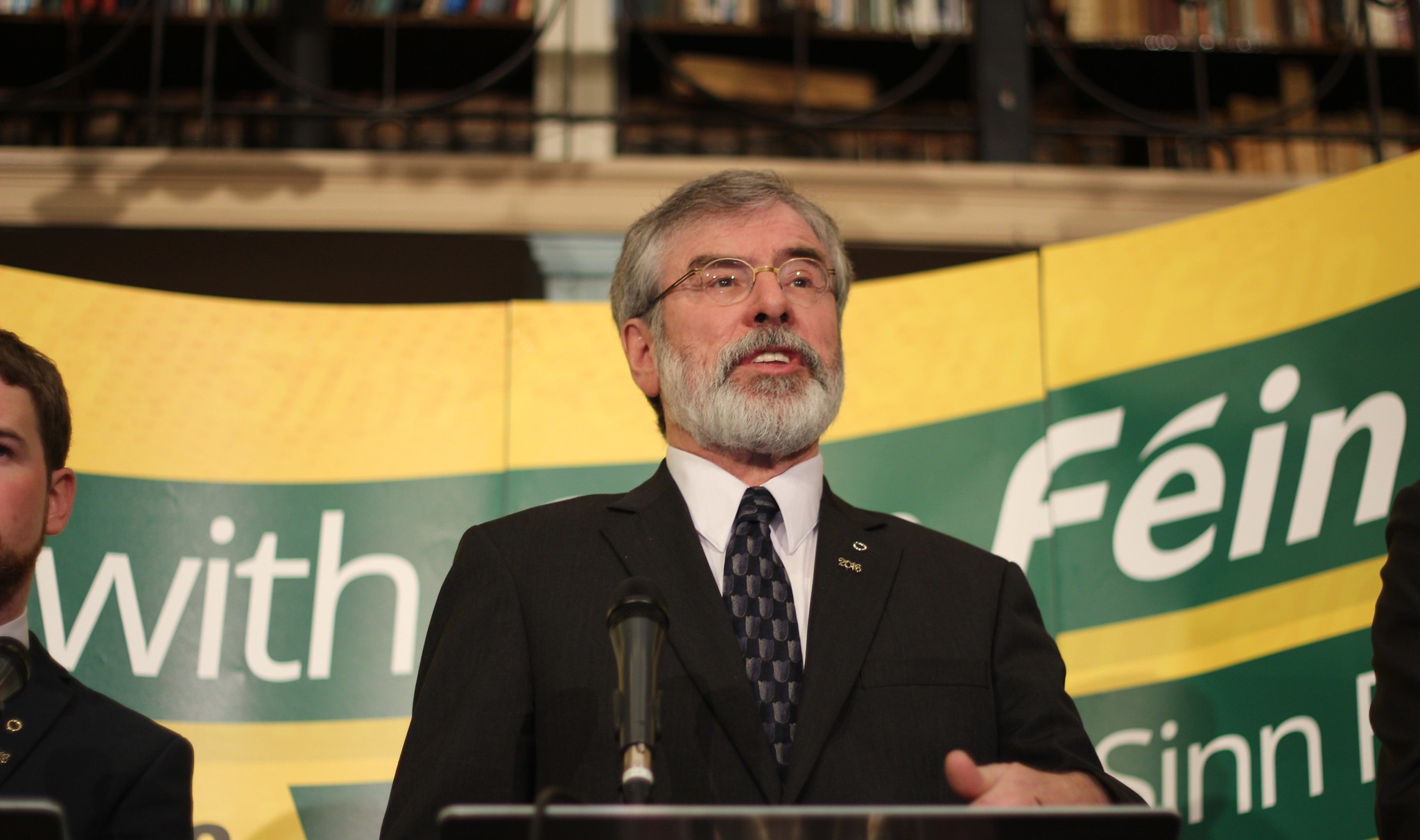

Those losing the right to compensation would include the former MP and Sinn Fein president, Gerry Adams.

He has already won a legal action directing the Northern Ireland Minister for Justice to reconsider its refusal to award him compensation under the miscarriage of justice scheme.

Internment orders

The basis for the Adams compensation lies in a declassified document dated 8 July 1974 which was found by researchers for the Pat Finucane Centre in the National Archives in London.

The document is a note from Charles Barry Shaw, the then Director of Public Prosecutions, to the Attorney General for Northern Ireland, Sam Silkin.

It concerns whether it was in the public interest to prosecute Adams (and three others) for their attempt to escape from prison on Christmas Eve 1973.

Shaw seeks direction from Silkin after receiving advice from a senior barrister. This advice raised the issue of whether the four internment orders, known as Interim Custody Orders (ICOs), were legal as they were not properly authorised by Conservative secretary of state for Northern Ireland, William Whitelaw.

“Possibly many other internees held under orders … may be unlawfully detained”

Shaw notes “the possibility of their detention being unlawful must appear” (presumably in court and therefore in public) and that “possibly many other internees held under orders which have not been signed by the secretary of state himself may be unlawfully detained”.

The clear implication is that Shaw was concerned that the illegality becoming public would prompt compensation claims and be more embarrassing and damaging to the public interest (and Whitelaw’s reputation) than dropping plans to prosecute the four men for their attempted escape.

Using the 1974 document, Adams’ legal advisors have successfully argued, during a ten-year court battle, that he and 200 others were imprisoned not only without trial but also illegally and that this was known at the time but was deliberately kept secret both from them and the courts.

Duty to examine

A second government document, marked “Secret” (which remains classified but has been viewed by Declassified UK) makes clear that Whitelaw’s legal responsibility went further than merely rubber-stamping internment orders.

It shows Whitelaw’s duty was to view and examine the evidence for each and every order. He failed to do so, however, delegating authorisation to sign the documents to a junior minister.

Under the then Labour government, the lively debate being conducted behind the scenes about wrongful internment orders was not disclosed at the time to either Crown or defence solicitors or to the judiciary.

The 1974 document records Silkin saying: “An examination of the papers concerning these prisoners revealed that applications for ICOs concerning these men had not been examined personally by the previous secretary of state for Northern Ireland [Whitelaw]”.

The document also makes clear that the incoming Labour secretary of state, Merlyn Rees, did carry out his statutory duty by looking at each case before he took the decision to deprive anyone of his/her liberty by imprisoning them for an indefinite period of time.

Based on these two documents, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in a May 2020 judgement that the order interning Adams was invalid.

The court concluded that Adams “was wrongfully convicted of the offences of attempting to escape from lawful custody and his convictions for those offences must be quashed.”

The same would also be true of the other three internees who attempted to escape with Adams and any other internees whose internment orders were not examined and approved by Whitelaw.

The estates of those who have since died can take legal action and many are already doing so.

No compensation

In May 2021, the Department of Justice in Belfast ruled Adams was ineligible for compensation. His lawyers succeeded in a judicial review challenge, however, and won.

The court ruled that, as there had been a miscarriage of justice, he was innocent of the crime for which he was convicted and therefore he met the test for compensation under the Criminal Justice Act 1988.

However, Adams has, to date, not received a penny.

It appears that, in an act of desperation to avoid paying out, the British government has decided to insert a clause into the unrelated “Legacy and Reconciliation Bill” to retrospectively legalise the defective internment orders.

The bill provides the perpetrators of alleged past crimes with a conditional amnesty and closes down access to justice for the families of those bereaved in the conflict in Northern Ireland.

‘Waiving the rules’

Seamus Collins, of McGrory & Co solicitors, who acts for Gerry Adams, said: “It has been a long and very winding road and it is far from over yet. London’s proposal would remove Adams’ legal rights, compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights, and it will be vigorously challenged through the domestic courts and the European Court if necessary”.

Paul O’Connor of the Pat Finucane Centre said they had “Immediately realised … it had major implications for all those interned during Whitelaw’s time as secretary of state. He was so insouciant about imprisoning people and throwing away the key that he never bothered to ask for, let alone, scrutinise the evidence”.

Adams says London’s current proposal is Orwellian, But it “comes as no surprise to those in Ireland and in countless other states around the world who have experienced British injustice. Another example of Britannia waiving the rules”.

The Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Bill is opposed by every political party in Northern Ireland, whether nationalist or unionist, as well as the Irish government and every domestic and international human rights organisation including Amnesty International and the UN.