- Charles’ visits tend to whitewash the Middle Eastern monarchies’ human rights abuses, often coinciding with repression of opposition activists or the media.

- He plays a key role in cementing UK relations with key allies, acting as a de facto high-level salesman for British arms exports and promoting military cooperation.

- While the palace emphasises his cultural visits, Charles’ meetings are often with senior military, intelligence and internal security officials.

- Charles is also the patron of the UK intelligence agencies.

Research by Declassified has found that Prince Charles held 95 meetings with ruling families in the Middle Eastern monarchies since pro-democracy protests threatened their power in the uprisings of a decade ago.

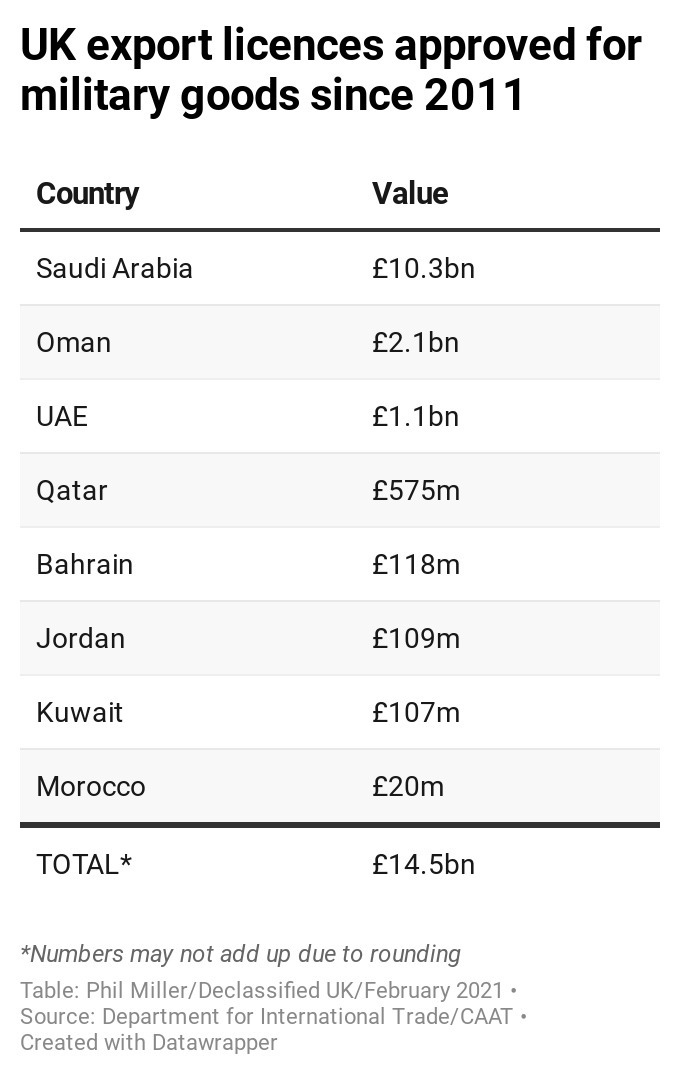

Charles’ diplomacy in the region, which comes at the request of the Foreign Office, has helped to cement controversial UK alliances with undemocratic regimes and promoted £14.5-billion worth of arms exports to them in the last decade.

During 2011, the year of the Arab Spring, Charles met six of the Middle East’s eight monarchs, from Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. He subsequently held numerous meetings with dynasties from Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Many of these visits took place just before or during specific acts of repression by these regimes – especially of opposition activists, the media or religious minorities – acts which have been regularly condemned by human rights groups.

All of the region’s royal families heavily repress opposition groups, but Qatar and Saudi Arabia have also supported and armed extremist groups in Syria and Libya, while the UAE has played a leading role with the Saudis in the devastating war in Yemen.

Whenever Prince Charles travels abroad, Buckingham Palace press releases highlight his visits to charitable causes, schools and hospitals, providing pictures of him and his wife Camilla – together known as the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall – with smiling children.

However, Charles also routinely meets senior military, intelligence and internal security figures, either on overseas trips paid for by the British public purse or at Clarence House, his official residence in London.

For Middle East visits, the publicity includes photos of Charles at mosques and Islamic heritage sites, burnishing his image as a ‘defender of faith’ and a bastion of religious tolerance. Almost invariably, such lines are repeated by Britain’s royal correspondents, who seldom pay attention to the politics and persecution that accompanies his trips.

Charles’ visits are part of the British royal family’s broader engagement with Middle Eastern monarchies in support of UK foreign policy. Part 1 of this investigation found that members of the royal family have met the region’s monarchies on 217 occasions since 2011.

Charles and the monarchs: the beginning of the Arab Spring

The willingness of Prince Charles to support fellow royals in the Middle East was evident from the outset of the Arab Spring, when he and Camilla dined with the King of Morocco, Mohammed VI, at his palace in Rabat on 4 April 2011.

In breach of international law, Morocco has long occupied its southern neighbour, Western Sahara. In November 2010, Moroccan security forces broke up the Gdeim Izik protest camp in the territory, where thousands of Sahrawi activists had pitched tents, causing deaths on both sides.

This unrest, which preceded the higher profile protests at the start of the Arab Spring in Tunisia, soon spread to Morocco itself, where students and teachers staged major demonstrations calling for curbs to the monarchy’s power. King Mohammed VI promised a package of reforms but many people continued to protest, calling for a constitutional monarchy days before Prince Charles was due to arrive.

Among the royal entourage was Clive Alderton, a career diplomat on temporary loan to Clarence House. He would return to the Foreign Office the next year – as UK ambassador to Morocco. To emphasise their support for the regime, while in Morocco Charles and Camilla visited a military base, watching a skydive by the 1st Brigade Infanterie Parachutiste.

Charles also laid a wreath at the tomb of King Hassan II, a move which sparked criticism from a protest leader who pointed out that the previous ruler of Morocco is known for the ‘Years of Lead’, a period during his reign in which hundreds of dissidents were tortured or killed.

A month after visiting Morocco, Charles met Qatar’s then prime minister, Sheikh Hamad bin Jaber Al Thani (“HBJ”) in London on 23 May 2011. One of the world’s wealthiest men, HBJ had previously been caught up in allegations of money laundering on an arms deal with BAE Systems.

Qatar, with its small and wealthy domestic population, was relatively untouched by the Arab Spring, but it was now playing an active international role, sending arms and finance to rebel groups in Syria and Libya, some of whom had extremist Islamist agendas.

Charles then flew in October 2011 to the Saudi capital, Riyadh, for one night, at a cost to the public of £67,215. There, he “presented condolences to the Saudi Royal Family” for the death of Crown Prince Sultan, who died in his 80s after growing enormously wealthy.

As Saudi Arabia’s long-standing defence minister, Sultan agreed to billions of pounds worth of weapons purchases from British arms giant BAE Systems, in deals marred by bribery.

The funeral came amid what Human Rights Watch called Saudi Arabia’s “unflinching repression to demands by citizens for greater democracy” in the wake of the Arab Spring. The kingdom had executed at least 61 prisoners that year alone, including a child, and a man accused of “sorcery”.

For the Prince of Wales’ sixth meeting with an Arab monarch in 2011, Charles welcomed Bahrain’s King Hamad to Clarence House in mid-December. Bahrain had faced the most significant popular opposition in the Gulf that year, and administered the most repression.

More than 40 people were killed, hundreds of public sector workers were sacked for supporting the protests and thousands of activists were arrested by the regime. The leaders of the pro-democracy movement were sentenced to life imprisonment.

In an attempt to placate some international concern, King Hamad set up a commission to investigate allegations of ill treatment. His meeting with Prince Charles came weeks after the commission had released its report, which recorded 559 allegations of torture.

2012: Horses over human rights

Charles did not travel to the Middle East the next year, but instead held six meetings with Arab royals when they visited London. A high level visit came on 14 June 2012, when Oman’s ruler Sultan Qaboos called on Charles and Camilla at Clarence House.

The day before, Human Rights Watch had spoken out against Oman’s “sweeping crackdown on political activists and protesters arrested solely for exercising their rights to freedom of speech and assembly”.

Qaboos, one of Britain’s oldest allies in the Middle East, had eliminated dissent, running one of the most closed countries in the region where political parties are banned and “insulting the Sultan” is a criminal offence.

When the Arab Spring erupted in early 2011, protesters staged sit-ins across Oman’s major cities to demand reform and condemn corruption. Qaboos responded with force, sending in police and soldiers who shot dead several protesters and arrested 800 in one city alone.

The following year, around the time Qaboos was meeting Charles in London, activist Khalfan al-Badwawi tried to expose how the Sultan was spending public funds. He held a protest in the capital, Muscat, to highlight how Qaboos had recently transported 110 horses inside two specially modified Boeing 777 jets to the UK.

There, Omani cavalry displayed a 10-man pyramid on horseback while other riders performed orchestral music in celebration of Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee – a grand party for her 60th year on the throne – inside the grounds of Windsor Castle.

Holding placards asking ‘who’s important – horses or humans?’, al-Badwawi’s protest was surrounded by thousands of riot police and he was later arrested, tortured and charged with “insulting the sultan”.

While Sultan Qaboos was in London seeing Charles and the Queen, al-Badwawi was being held in solitary confinement in Oman, subjected to constant sleep deprivation and repeated interrogation over the course of 32 days.

The following month, July 2012, Charles welcomed the Emir of Kuwait to England, driving with him in a “carriage procession to Windsor Castle”. A state banquet was thrown, involving most of the UK royal family.

The visit came after months of crackdowns in Kuwait, such as the suspension of Al Dar newspaper and the sentencing of blogger Hamad al-Naqi to 10 years imprisonment for tweets that allegedly insulted the rulers of Bahrain and Saudi Arabia plus the Prophet Muhammad.

Charles saw out 2012 with two quick visits from other Arab royals. On 12 December, he had a meeting with King Abdullah of Jordan, which was held weeks after the suspicious death of a 20-year-old limousine driver Najm al-Din ‘Azayiza at the hands of Jordanian military intelligence officers.

The death followed a year of repression in Jordan, with the editor of the Gerasanews website, Jamal al-Muhtasab, spending weeks in detention after military prosecutors charged him with “subverting the system of government”.

2013: Celebrating the Saudi national guard

Amidst the ongoing repression in the Middle East, 2013 saw Charles and Camilla holding 15 meetings with four Arab monarchies in March alone.

They began on 11 March with a trip to Jordan for sessions with King Abdullah, his wife and various princes and princesses. Charles and Camilla then proceeded to Qatar to meet the Emir’s wife, Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, and the prime minister HBJ.

The couple then flew to Riyadh military air base, arriving on 15 March 2013, five days after Saudi authorities had sentenced leading rights activists Dr Mohammed al-Qahtani and Dr Abdullah al-Hamid to 10 and 11 years in prison respectively.

According to Human Rights Watch, the men were convicted on charges of “breaking allegiance with the ruler,” and “setting up an unlicensed organization” – a reference to their advocacy group, the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association, which was forced to close.

Charles and Camilla visited the headquarters of the Saudi Arabian National Guard (SANG) to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the British Military Mission – a highly secretive programme in which UK army officers are embedded in the SANG, a notorious internal security unit that played a key role in suppressing Arab Spring activists in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain.

According to Campaign Against Arms Trade, the Saudi visit came while British arms giant BAE Systems was trying to agree on a price for selling more Typhoon fighter jets to the Kingdom, at a time when Britain’s Serious Fraud Office was investigating alleged corruption on a SANG communications contract with another UK arms dealer.

To conclude their March 2013 tour of the Middle East, the couple touched down in Oman, where they were greeted by the country’s unelected deputy prime minister, Sayyid Fahad bin Mahmood Al Said, before joining Sultan Qaboos for dinner at his Bait al Baraka Palace in Seeb.

According to Clarence House, the trip was designed to “promote Britain’s diplomatic, commercial interests” in Oman, which at that time mainly concerned a £2.5-billion deal to buy 12 Typhoon and eight Hawk jets from BAE Systems.

Omani activist Khalfan al-Badwawi tried to organise a protest against the latest visit from Prince Charles. However, masked Omani special forces swooped on his car in a high-speed manoeuvre and bundled him into solitary confinement for five days in mid-March 2013.

Oman’s domestic security force subjected him to psychological torture techniques and he was only released once Prince Charles had left the country.

In May 2013, Prince Charles welcomed the unelected president of the UAE, Sheikh Khalifa, to Clarence House following his visit to Downing Street. The UAE state visit came at a time when BAE Systems wanted to sell the regime 60 Typhoon jets for around £3-billion, during increased repression in the Emirates.

From March to July 2013, the UAE held a mass trial of 94 activists accused of ties to al-Islah, an offshoot of Egypt’s then ruling Muslim Brotherhood party which was advocating for political reform in the Emirates. The case eventually saw 69 of the men convicted for attempting to overthrow the government, with sentences of up to 10 years imprisonment.

In late 2013, Charles met Bahrain’s Crown Prince Salman and Jordan’s King Abdullah, this time at Clarence House. Since Charles’ visit to Jordan earlier in 2013, the authorities had stepped up attacks on press freedom by blocking over 260 news websites.

In September 2013, in a sign of solidarity among the Middle Eastern monarchies, Jordanian police arrested the publisher and editor of the Jafra News website for posting a video critical of Qatar’s royal family.

2014: Saudi sword dance

The following year provided another opportunity for Prince Charles to perform his role as a de facto salesman for BAE Systems, this time in Saudi Arabia and Qatar. On 17 February, Charles flew from RAF Brize Norton to Riyadh, in what was reported to be his 10th trip to the kingdom in his lifetime.

The human rights situation had deteriorated since his last visit in 2013, with international concern focusing on the sentencing of liberal blogger Raif Badawi to six years in prison and 600 lashes for “insulting Islam” (later increased to 10 years and 1,000 lashes).

Charles’ team was met by Saudi prince Miteb bin Abdullah Al Saud, commander of the notorious national guard, and he later met seven other princes, including Muqrin bin Abdulaziz, who headed Saudi intelligence during the Arab Spring until 2012.

Charles also met Abdulaziz bin Abdullah, the deputy foreign minister who reportedly helped set up a “nerve centre” in Turkey to try to topple Syrian leader Bashar Al Assad, with Qatari support. It would soon emerge that Saudi aid for Syrian rebels was directed towards fundamentalist groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra, an Al Qaeda affiliate.

It is not known what was said at these meetings, because Prince Charles is exempt from Britain’s freedom of information laws. However the following day BAE Systems announced it had finalised a multi-billion pound weapons sale to Saudi Arabia, for the supply of Typhoon fighter jets.

After years of delay, the Saudis may have been persuaded to sign after Charles joined them in a traditional sword dance, adorned in Arab dress. The incident drew sharp criticism from campaigners, given that Saudi Arabia had executed at least 79 people the previous year, often by beheading.

Travelling on to Doha, Charles met Qatar’s foreign minister before making whistle-stop calls in the UAE and Bahrain to conclude his tour of the Gulf. The combined costs of this four-stop tour, including the reconnaissance trip, came to almost a quarter of a million pounds.

Although Charles had no problem entering the UAE, where he met the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, a month earlier the Emirates had denied entry to a member of Human Rights Watch and put two other staff members on a travel blacklist as “dangerous to public security”.

2015: Half mast affair

Throughout 2015, as the human rights situation in the Middle East worsened, Charles continued to court Arab royals.

In January, he and David Cameron rushed to Riyadh, spending £101,792 on a specially chartered flight, to offer condolences to the Saudi ruling family for the death of King Abdullah, while flags were flown at half mast on UK government buildings.

Such symbolic acts sparked criticism from some in the UK, especially as blogger Raif Badawi had recently received the first 50 of his lashings.

Charles’s subsequent tour of five Middle Eastern monarchies began on 7 February, when he took a specially chartered flight from RAF Brize Norton with his military aide, Lt Col Bevan and veteran diplomat Jamie Bowden, who was UK ambassador to Oman and Bahrain during the Arab Spring.

After two nights in Jordan, Charles flew on to Kuwait and then to Riyadh for meetings with five senior members of the Saudi royal family. Despite Charles highlighting human rights and concern for Islamic heritage during the visit, the next month Saudi Arabia unleashed Operation Decisive Storm, a devastating air attack on its poorer neighbour, Yemen.

It would entail what a UN expert called “the ruthless destruction of one of the oldest cities in the world”, as Yemen’s historic capital Sana’a was blitzed. Many of the bombs in the war would be dropped from BAE Systems-made jets, which Charles had helped to sell to Saudi Arabia.

Charles finished his Gulf tour with a day trip to Qatar and the UAE which would soon join the Saudi-led airstrikes. There he met Qatar’s Emir and the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi. Weeks earlier, on 25 November 2014, the Emirates sentenced an activist, Osama al-Najjar, to three years in prison for charges such as “damaging the reputation of UAE institutions”.

Charles returned to the UK on 12 February 2015, but less than two weeks later he had another meeting with the Saudi royal family, this time in London where he had dinner with the deputy Crown Prince at Clarence House. This flurry of activity meant that Charles clocked up 19 meetings with Arab royals in the first two months of 2015.

The next and final encounter for 2015 came in November on the sidelines of UN climate talks in Paris, where he met Crown Prince Salman of Bahrain. When the country’s most prominent human rights activist, Nabeel Rajab, took to Twitter to denounce Bahrain’s role in the Yemen war, he was arrested.

It was part of a major crackdown on civil liberties in Bahrain that year, which included sentencing the secretary general of the country’s largest opposition party to four years in prison. The number of arrests since the Arab Spring, and the ongoing torture of detainees, led to an uprising in Jau prison, where political inmates were being held.

Their protest was put down with teargas and birdshot, allegedly followed by further torture and humiliation, including making detainees strip down to their underwear and shout chants in support of Bahrain’s king.

2016: Reaping the whirlwind

By 2016, opposition movements in many Gulf monarchies lay in ruins. Five years of systematic counter-revolution since the Arab Spring had seen a generation of intellectuals and activists taken off the streets or social media, put in prison, tortured or simply killed.

But Britain’s next king indulged in a further 24 meetings with Arab royals in 2016, kicking off with an event at the Anglo-Omani society in London on 27 January, attended by Sayyid Shihab bin Tariq Al Said, Oman’s third in line to the throne.

By that time Charles’ staff included Major Matt Wright, who served as his assistant equerry. Wright would go on to be a commander in the 90-strong team of British forces on loan to the Sultan of Oman.

Prince Charles “expressed his joy” at being invited to the Anglo-Omani society event and described the autocratic Sultan of Oman as “far-sighted”. Later that day, Charles reportedly received Sayyid Haitham, Oman’s culture minister who would soon become Sultan.

Three weeks earlier, a British judge had granted asylum to Omani dissident Khalfan al-Badwawi, ruling that “he would be at real risk on return to Oman because of his political opinion”. The judge accepted expert evidence that al-Badwawi was “one of the most vocal and public advocates for democratic reforms in Oman”.

Days after the Anglo-Oman society event, Charles was visited at Clarence House by the Emir of Kuwait and the King of Jordan. Between their visits, he had time to visit the MI6 headquarters in central London, in his role as patron of the UK’s intelligence agencies.

Planning for Charles’ next trip to the Gulf started in September 2016, when palace records show the Prince’s staff spent close to £20,000 flying to Bahrain and Oman on a “reconnaissance tour”. On 4 November 2016, Charles and Camilla flew out to the region on a specially chartered flight from RAF Brize Norton, costing the public purse an additional £72,756.

Upon landing in Oman’s capital, Muscat, they were met by Sayyid Haitham and had dinner with Sultan Qaboos. True to form, Charles took part in a traditional sword dance, as he had done in Saudi Arabia.

A statement issued by Clarence House mentioned the trip’s political aims, which included promoting “the UK’s partnership in the region in key areas such as… military cooperation”. Towards the end of their trip, Charles met British troops on loan to the Sultan, which numbered around 195, including senior officers.

The visit came after months of attacks on freedom of speech in Oman. On 8 February 2016, a former Omani diplomat, Hassan al-Basham, had been sentenced to three years in prison on charges that included insulting the Sultan on social media – he would later die in prison.

In the summer of 2016, three senior staff at the country’s only independent newspaper, Azamn, had been arrested and in August the paper was ordered to close by the Internal Security Service.

Immediately after touring Oman, the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall arrived in the UAE, on 6 November 2016. During their visit, they met senior figures from the ruling families, including the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and the UAE’s prime minister, Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, as well as his wife, the Jordanian Princess Haya.

Other meetings included the Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE military, a point missed from the palace’s press release. Meetings with the UAE’s military at this time were particularly sensitive given its offensive role in Yemen, where it was using mercenaries to fight the ground war and holding prisoners in black sites where torture was rife.

Human Rights Watch raised concerns about Charles’ trip to the UAE, highlighting that 43 British citizens had complained of torture or ill treatment while being detained over the previous five years. One man, Lee Bradley Brown, had died in solitary confinement in a Dubai police cell, after officers allegedly beat him.

The final stop on Charles and Camilla’s Gulf tour would prove to be the most controversial, when the couple stopped off in Bahrain on 8 November 2016. It came just weeks after Bahraini exiles in London protested near King Hamad’s limousine as he pulled into Downing Street.

In retaliation for that protest, Bahraini authorities targeted the family of one refugee, Sayed Alwadaei, detaining and violently interrogating his wife Duaa as she tried to leave Bahrain for London with their 19-month-old son. It was a signal that lawful protest in Britain would result in retribution in Bahrain.

After being reunited with his wife and son in London, Alwadaei told the Independent: “Prince Charles’ visit is giving the Bahrain authorities a green light to continue their oppression and using him to whitewash human rights abuses.”

Charles and Camilla went ahead with their trip to Bahrain, where they were greeted upon arrival by the Crown Prince, before dining with King Hamad and his wife Sabika at Al Roudha Palace.

Almost immediately after the trip, Bahraini authorities arrested an opposition politician, Ebrahim Sharif, who had spoken to a US news agency about the royal visit. Sharif had told the Associated Press that Charles’ visit to Bahrain could “whitewash” the regime’s crackdown on dissent.

Prosecutors charged him with “openly inciting hatred of the political system in Bahrain” although, due to an international outcry, charges were dropped within a fortnight.

2017: Typhoons, horses and a firing squad

After an intense series of meetings with Arab royals in 2016, for the rest of the decade Charles confined himself to just eight more meetings with Gulf monarchies, as younger members of the royal family took on more of the engagements.

In March 2017, Charles received Qatar’s unelected prime minister, Sheikh Abdullah, a member of the royal family and former interior minister. Sheikh Abdullah also met prime minister Theresa May at Downing Street where the pair “agreed on the importance of our security co-operation, and committed to strengthening our collaboration on cyber security and defence”.

Qatar was then a member of the Saudi-led coalition bombing Yemen, a military campaign that was creating the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Later in 2017, Qatar agreed to buy 24 Typhoon jets from BAE Systems for £5-billion.

Following the Qatari visit, Charles again met Bahrain’s Crown Prince Salman in mid-May 2017 at Clarence House. It came days after Salman’s father, King Hamad, had seen Charles’ mother and younger brother Andrew at the Royal Windsor Horse Show.

Bahraini exiles protested at the event, resulting in their family members being arrested at home –the sixth time since the Arab Spring that Gulf activists had been punished specifically for speaking out against Royal visits to or from the UK.

The arrests were part of a pattern of mounting repression in Bahrain which saw three political prisoners executed by firing squad one night in January 2017. It was Bahrain’s first use of the death penalty since 2010, and the men had allegedly been tortured into making false confessions.

UN special rapporteur, Dr Agnes Callamard, described them as “extrajudicial killings”.

Days after Charles met the Crown Prince on 16 May 2017, Bahrain banned the main secular opposition party, the National Democratic Action Society, and shut down the country’s only independent newspaper, Al Wasat.

2018: Dining with executioners

The following year, in March 2018, Charles and his son William held a dinner at Clarence House for Saudi Arabia’s new Crown Prince, the young Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS). It was part of a major Foreign Office public relations operation to portray MBS as a reformer, in an effort to improve Riyadh’s reputation after high profile controversies.

Britain’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Simon Collis, claimed the speed of change in Saudi Arabia was “actually quite breathtaking”, in a video specially filmed to promote the MBS visit. Boris Johnson, then foreign secretary, wrote a gushing column in The Times, titled “Saudi reformer Mohammed bin Salman deserves our support”.

Days after the visit, it emerged that BAE had edged closer to sealing a multi-billion pound arms deal with Saudi Arabia to sell another 48 Typhoons, to add to Riyadh’s existing fleet of Typhoons that was bombing Yemen.

Although the efforts of Whitehall and the House of Windsor to cheerlead for MBS may have persuaded some people, the illusion was shattered in October 2018, when Saudi authorities murdered and dismembered Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi at their consulate in Turkey.

2019 and 2020: Funerals but not farewells

Charles managed only one encounter with a Gulf monarchy the following year, perhaps dissuaded by the Khashoggi murder. He met Kuwait’s defence minister and deputy prime minister Sheikh Nasser at Dumfries House, one of Charles’ Scottish estates, in May 2019.

Then in January 2020, British foreign policy in the Gulf suffered a major loss with the death of Sultan Qaboos of Oman, the longest-serving ruler in the Middle East, who had been in power for 50 years.

Charles immediately flew to Muscat to offer his condolences and usher in the Sultan’s unelected successor, Haitham, the former culture minister. Charles’ specially chartered flight from Aberdeen to Muscat cost the public £210,345 for the one-night trip.

Prime minister Boris Johnson also flew out with ten officials to pay his respects, costing a further £143,276. Meanwhile, defence secretary Ben Wallace went on a scheduled flight which cost just £4,697.

Haitham’s position as heir to the throne was only publicly revealed upon the death of Qaboos, although Charles had already met him on several previous occasions. Those earlier encounters suggest Clarence House may have been privy to Oman’s secret line of succession.

Qaboos had done nothing in his final years to prepare for a transition to democracy. He had focused on extinguishing Oman’s last site of resistance, cracking down on the pro-autonomy movement in Musandam, the peninsula on Oman’s northernmost tip.

Six men from Musandam had been sentenced to life imprisonment in Oman in 2016 on what Amnesty International called “vague grounds of national security”. The human rights group believes the men were engaged in “peaceful activism and campaigns for the rights of Musandam’s residents”, who were suffering from house demolitions.

The coronavirus pandemic would prevent much international travel for the rest of 2020, but Charles did manage to fit in one more meeting with Bahrain’s monarchy in early March, when the King’s son and national security adviser, Major General Nasser, visited Clarence House.

Nasser is accused of involvement in the torture of activists during the Arab Spring. According to Bahrain’s state media agency, during their meeting Nasser “lauded [the] strategic partnership binding the Kingdom of Bahrain and the friendly United Kingdom”, and Charles wished “the Kingdom of Bahrain further progress and prosperity”.

Then in October 2020, Charles flew to Kuwait for the Emir’s funeral. The cost of the trip is yet to be published by Buckingham Palace, which flew its union flag at half mast to commemorate the Emir’s passing.

Photos from the trip show Prince Charles was accompanied by General Sir John Lorimer, Britain’s outgoing senior army officer in the Middle East who maintained close military relations with the UK’s autocratic Gulf allies.

The most recent meeting between the House of Windsor and Arab royalty came in December 2020 when the Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, Mohammed bin Zayed, visited Charles and Boris Johnson in London.

The meetings took place despite mounting criticism from UN Experts about the conduct of Emirati forces fighting in Yemen, commenting: “Civilians in Yemen are not starving; they are being starved by the parties to the conflict.”

A Foreign Office spokesman told Declassified: “Official royal visits are undertaken by Members of the Royal Family at the request of the Government to support British interests around the globe.”

A Clarence House spokesman told Declassified: “All of The Prince of Wales’s overseas visits are undertaken at the request of HMG and are organised by the Royal Visits Committee. The destinations are published in advance and the international media are invited to attend the visits in order to cover the engagements in detail.”

He added: “All decisions relating to travel are made taking into account the time available, costs and the security of the travelling party. The costs are published annually as part of the Sovereign Grant Annual Review.”

This is Part Two of our investigation into the British royals. Read Part One here.