A coroner in Northern Ireland has criticised the Ministry of Defence for failing to change the 1970s military ‘Rules of Engagement’ on firing plastic bullets – despite repeated advice to do so from experts at three separate government scientific units.

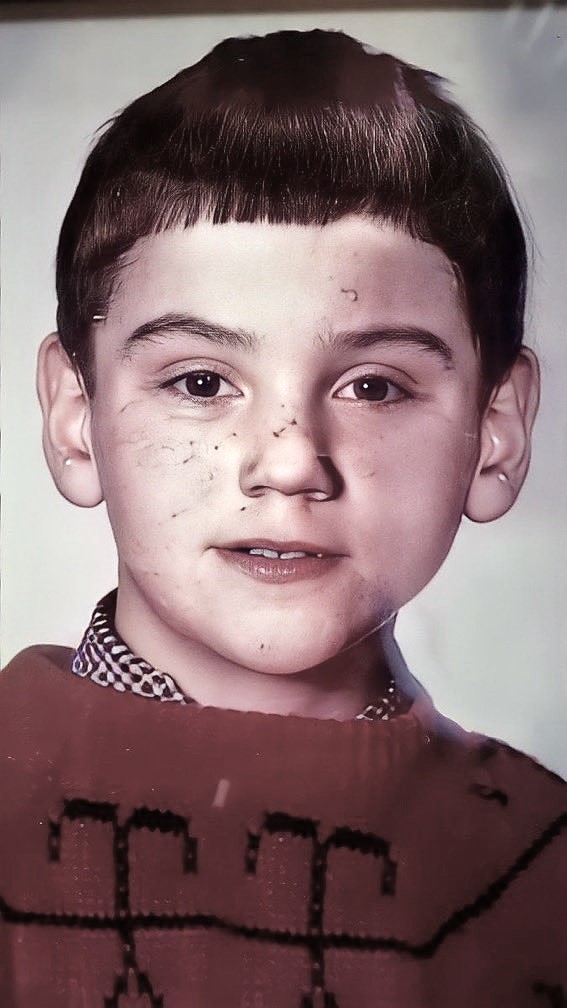

The MoD’s refusal to change its rules, said Judge Patrick McGurgan, had led to the “unjustified” killing of a 10 year-old Belfast boy, Stephen Geddis, who was shot in August 1975.

His skull was crushed by a plastic bullet fired by a soldier who was accorded anonymity and known only in court by the cipher “SGM15”.

This is just one of several scientific controversies over the use of plastic and rubber bullets in Northern Ireland which killed 17 people during The Troubles, of whom eight were aged under 16 and all except one were Catholic.

British soldiers killed 11 and police from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) killed six. None were armed, including Stephen Geddis.

The contempt with which someone within the British military regarded the 10 year-old’s death can be judged by a handwritten note, added to a typed declassified “Director of Operations” brief, dated 28/29 August 1975.

It reads: “Comfortable! In his coffin!”.

Lying to the inquest

Judge McGurgan ruled that soldier SGM15 had lied to the inquest and refused to accept his statement that he could not remember the incident. SGM15, he said, had claimed he wanted to assist the bereaved family “but I do not accept this” he said.

“I consider that he [SGM15] has a better memory of the event than he represented in his oral evidence”, said McGurgan – who reserved even stronger criticism for the Ministry of Defence.

McGurgan cited the 1975 ‘Rules of Engagement’ for British soldiers which stated that baton rounds (plastic bullets) should be fired in front of people in a crowd so they bounced or ricocheted before hitting their target.

“There was no documentation available to show that this information was provided to the soldiers.”

The same Rules, however, said the weapon was not acceptable for use against women and children while another MoD document said both baton rounds and CS gas may be “considered too harsh a reaction” if women and children were present in a crowd.

Alan Hepper, Senior Principal Engineer since 1988 at the MoD Defence Science and Technology Laboratory, accepted there had been no scientific tests to examine the ricochet rule, although some testing was being carried out while the bullets were being fired at people in Northern Ireland.

Under cross-examination at the inquest, Hepper also accepted that, “despite the knowledge of injuries caused by baton rounds, there was no documentation available to show that this information was provided to the soldiers”.

‘Indiscriminate’

Documents dating back to September 1972 showed a consultant at the Chemical Defence Establishment (CDE) at Porton Down in Wiltshire had found that baton rounds bounced off the ground “invariably rose to about head height” as they reached their target and “the flight path was unpredictable”.

It was “safer to fire this particular baton directly at the trunk”, the consultant found.

Hepper said there was a recommendation on further testing as “the head is the most vulnerable structure to projectile impact” but he knew of no paperwork to suggest this had been done and he accepted the risk to children of a strike “causing lethal skull injury would be higher”.

The Coroner said that despite this absence of testing and “the risk posed by ricocheted baton rounds”, the Rules of Engagement, which stated “the rounds must, whenever possible, be fired at the ground”, continued to apply.

In May 1974, the MoD’s operational testing body (the Infantry Trials and Development Unit, ITDU) reported that the failure of the military authorities to change the Rules was causing Porton Down increasing exasperation at the MoD’s “intransigence in the face of scientific opinion”.

A third government institution, ‘MO4’ (a division within the MoD relating to Northern Ireland) wrote a “strongly worded letter” in September 1974 stating baldly that, “by bouncing the round” the British Army could be accused of deliberately firing the weapon in “an indiscriminate” manner.

Hepper accepted that, by early-mid 1974, the three government agencies had all said the bullets should not be bounced off the ground.

Change in policy

Hepper accepted that Stephen Geddis’s death contributed to a change in policy in firing PVC rounds.

In his judgement, McGurgan cited a letter from CDE’s director to the legal secretariat of the MoD on 26 August 1977 informing it that the rules had changed in December 1975, just four months after the ten-year-old’s death.

Padraig Ó Muirigh, a solicitor representing the Geddis family, queried why the RUC had rejected evidence from a military whistleblower in 1995 of a cover-up. Although 10 civilian witnesses had given supporting evidence, police rejected their statements as “tainted” because they were “anti-British in their attitude”.

When this was raised at the inquest, the officer responsible could give no explanation for his conclusion. This led Ó Muirigh to claim the officer had developed the concept of a “suspect community” whose evidence could be easily dismissed.