Threats designated by the national security establishment are revealed by the current health crisis to be very different to the primary risks the UK public faces, and a new security paradigm needs to be developed, centred around public safety.

In 2013, for example, the UK Cabinet Office’s National Risk Register for Civil Emergencies warned that a global disease outbreak was likely within five years. Despite that, the government’s subsequent pandemic planning remained unfit for purpose. That very year, the UK’s Centre for Health and the Public Interest, a public health think-tank, warned that Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) was unprepared for the impact of such a pandemic.

The centre’s report listed a litany of problems. The NHS is “already struggling to deliver on the ‘day job’ of routine emergency admissions,” it warned, “so would be exceptionally challenged by a crisis such as a flu pandemic”.

The report criticised “a lack of appropriate skills and organisational memory” and blamed the “market-based” system for leaving the NHS “ill-prepared for sudden and exceptional events, putting in question our reliance on increasing numbers of private providers.”

Three years on, in 2016, NHS capabilities were tested during a three-day training exercise, Operation Cygnus. The exercise revealed broken lines of coordination between hospitals, Whitehall and disease-tracking experts.

Then UK chief medical officer, Professor Dame Sally Davies, said that during the exercise that the NHS’ inability to cope “killed a lot of people”, adding, “it became clear that we could not cope with the excess bodies.”

A failed paradigm

Throughout this period, the UK has continued to allocate billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money to “defence” expenditure which has failed to protect Britons from the unfolding impacts of a devastating and long-anticipated global pandemic.

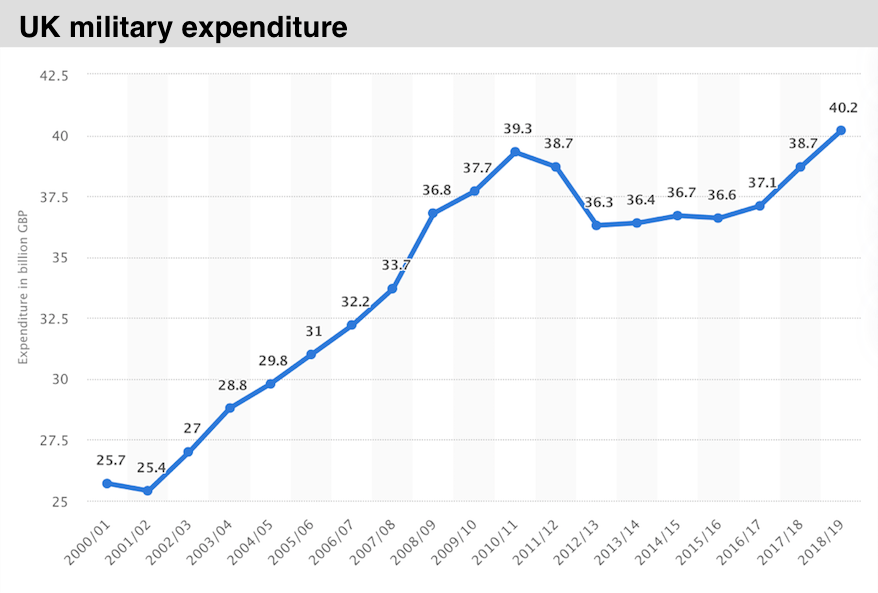

Since 9/11, the British government has increased its annual military spending from £25bn to £40bn. Last year alone, military expenditure rose by £2.2 billion.

Over the last two decades, the UK has spent a total of £648 billion pounds on the military – almost double Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s £350 billion bailout to keep the economy afloat during the coronavirus (COVID19) crisis.

The British establishment’s traditional approach to national security has emphasised the military and focused on terrorism, espionage, cyber warfare or proliferating weapons of mass destruction. What has barely been addressed is the likelihood of global pandemics affecting the UK public, including the complex and long-lasting consequences of the novel coronavirus.

The traditional approach to “security” has been impotent in safeguarding the British public from the real challenges of the 21st century.

The current security paradigm involves massive UK spending every year to uphold a global military posture. This is ultimately designed not to protect British citizens but to serve the interests of the establishment, especially its desire to remain a global power with major military intervention capabilities, and which also benefits corporations in the defence, energy, mining and other sectors.

This focus has meant that robust preparations for an inevitable global pandemic and public health crisis have fallen by the wayside.

The British national security establishment has focused on bulking up conventional military forces to counter states such as Russia and Iran. In addition, around £5.2 billion last year was dedicated to the Trident nuclear weapons programme. To maintain and replace Britain’s nuclear-armed submarines up to 2070 will cost around £172 billion by one estimate, five times more than the official Ministry of Defence figures.

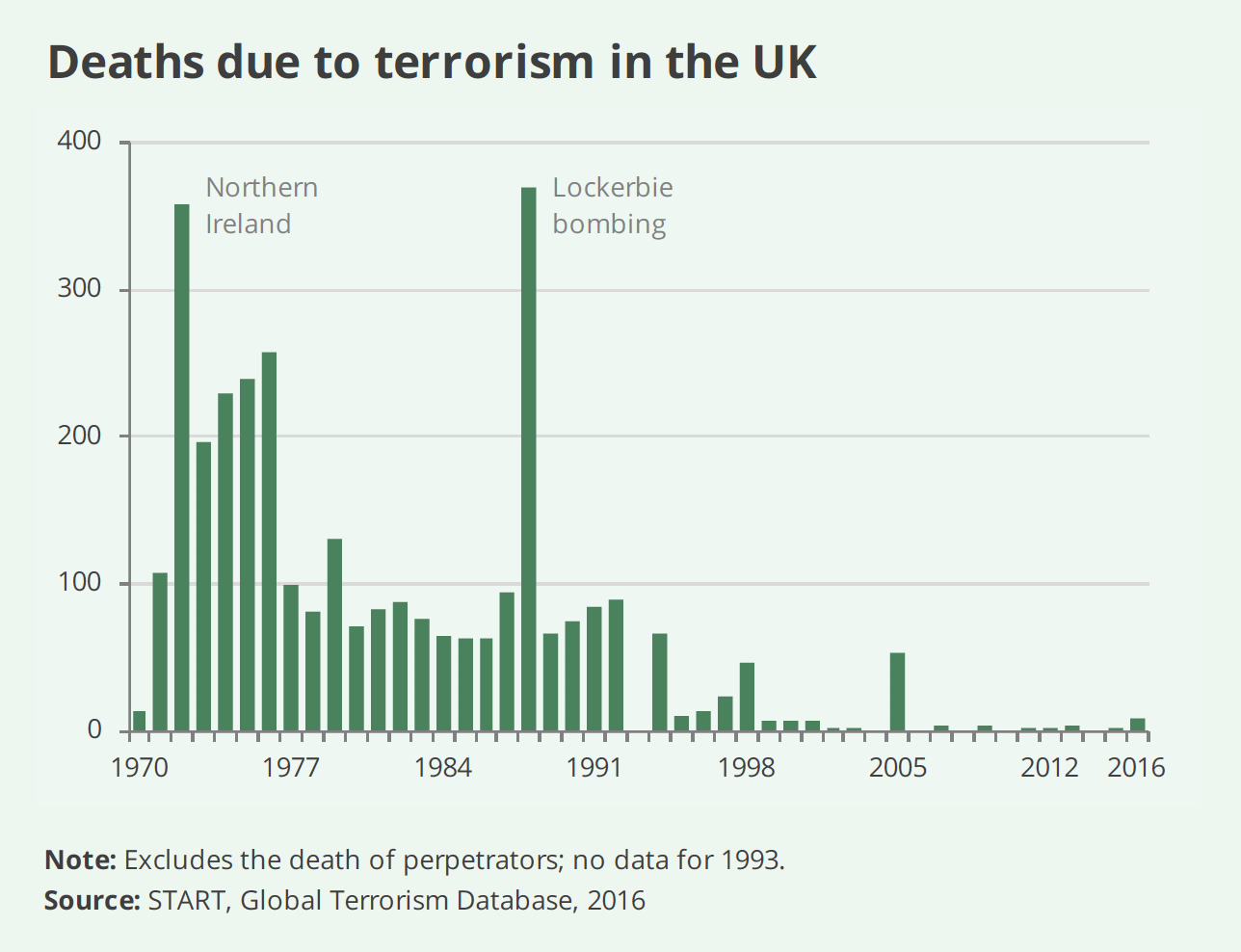

The threat from terrorism has declined, judged over recent decades. During the 1970s, as much as 70-80 percent of terrorism fatalities occurred in Western Europe. Yet by 2017, only 0.3 percent of terrorism deaths took place in the region.

In Britain, over the nearly two decades since 9/11 there have been just under 100 deaths from terrorism, with the scale of attacks having declined dramatically since the 1970s.

Protecting lives – or GDP?

The fatalities anticipated from the coronavirus epidemic in Britain are likely to far outweigh the death toll from recent terrorist attacks.

On 16 March, scientists at Imperial College, London advising the UK government on the COVID19 strategy found that prime minister Boris Johnson’s “mitigation” approach was heading for a “best-case” scenario of some 250,000 deaths in the UK due to the NHS being massively overwhelmed and unable to provide specialised treatment to those requiring critical care.

This was because the government had, for nearly two months, refused to introduce any “social distancing” measures – strategies to slow the spread of the disease by ramping down social activity. As a result, while the belated shift to more stringent “suppression” efforts may avoid this outcome, the Imperial College model suggests it is still likely to lead to tens of thousands of deaths.

The prior refusal to invest sufficiently in reorganising the NHS, and failing to act in precautionary fashion to avoid the risk of deaths, seems to have been influenced by the government’s insistence on assessing the potential impact of suppressive measures on GDP.

School closures, for instance, were avoided until 20 March. One concern, it seems, was that they would reduce national economic activity. In order to “weigh up the benefits and risks” of shutting down schools, the government was considering research warning that closures lasting four weeks would slash GDP by 3 percent.

This should not be surprising since Britain’s national security complex functions not only largely to protect a nexus of powerful elite interests, but also often amplifies the very threats it purports to be defending against.

Projecting influence

This can be seen by studying government annual reports produced in relation to Britain’s National Security Strategy. This was launched by the government in 2015 and produced its first annual report in 2016, with an updated version in July 2019, which describes one of its core aims being “to project our global influence.”

Combating international terrorism and violent extremism is a consistent theme of the strategy, largely because it provides a justification for military spending. Yet the strategy fails to acknowledge the connection between the rising threat of Islamist terrorism and the UK’s alliance with governments complicit in sponsoring that terrorism.

In fact, the 2019 document refers to the UK commitment to building “a permanent and more substantial UK military presence” in the Gulf region, primarily by increasing “the range and depth of activity in support of our Gulf partners.” Removed from this report is the 2015 version’s mention that the government aims to protect “the flows of energy and trade in the region”.

The 2019 document does not acknowledge what should be done to combat what the foreign affairs parliamentary committee described as evidence of “financial donations” to the Islamic State (ISIL or ISIS) terrorist network from wealthy Gulf donors including royal families.

According to the committee, Foreign Office officials admit that “some governments in the region may have failed to prevent donations reaching ISIL from their citizens”. Similarly, leaked emails from former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in 2014 alleged that “the governments of Qatar and Saudi Arabia… are providing clandestine financial and logistic support to ISIL [IS] and other radical Sunni groups in the region”.

The 2019 UK strategy document goes on to praise “UK-led efforts… to bolster the peace process and encourage an end to the violence” in Yemen, but ignores Britain’s crucial role in supplying weapons to Saudi Arabia and support for Saudi airstrikes. In 2017, the US West Point Military Academy’s Combating Terrorism Center described the war in Yemen as “a gift to al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.”

The document also discusses the British role in “tackling the drivers of conflict and uncontrolled migration around the world”, especially “the migration crisis in the Mediterranean”, noting the deployment of British “naval assets and expertise” to support its European partners.

Yet it ignores how Britain contributed to the migration crisis, notably through its role in NATO’s military intervention in Libya in 2011. The intervention, which even the Royal United Services Institute concluded was a “strategic failure”, led Libya to become a failed state, ISIS safe haven and key driver of mass migration to Europe.

Protecting “revenue”

The government’s 2016 National Security Strategy annual report noted, “We are enhancing our support to the defence and security export sector”, adding that “exporting is key to sustaining the UK’s industrial base in the long term”. It stated that “support to defence exports is now a core task for the MoD.”

At the time, British arms sales went to 21 out of the Foreign Office’s list of the top 30 human rights violators, including the Gulf kingdoms. The report failed to say how this aligned with the government’s stated commitment to “cutting off the supply and availability of firearms to criminals and terrorists”.

But the beneficiaries of the programme were alluded to when the report referred to the opportunity for “hundreds of millions of pounds in revenue for the UK”, meaning its military-industrial complex.

The UK needs a national and independent assessment of the extent to which the biggest threats to society are being exacerbated by the very structures that are supposed to keep Britons secure, and to reshape national security to focus on the real needs of the public.

Nafeez Ahmed is editor of the crowdfunded investigative journalism platform INSURGE INTELLIGENCE and Executive Director of the System Shift Lab.