The war in Ukraine has provoked concern about the use of nuclear weapons, heightened by Russia’s plan to base tactical nuclear arms in Belarus.

While the US and Russia have made no secret of their development of these dangerous, indeed potentially devastating, additions to traditional nuclear arsenals, British military planners have also been in on the act – rather more quietly.

The British government, far from taking measures to reduce nuclear tensions in recent years, itself announced, in 2021, that it planned to increase the cap on Britain’s nuclear stockpile to 260 warheads, a 40 per cent increase on previous commitments.

More recently, Britain has refused to comment on reports of a planned new deployment of US tactical nuclear weapons to the American air force base in Lakenheath in Suffolk.

With the exception of the Scottish National Party and Green Party, all British political parties are backing, with growing enthusiasm, the policy of maintaining a Trident missile submarine “continuously at sea”, at an initial estimated cost – not disputed by the Ministry of Defence – of more than £200bn.

The deployment of British nuclear weapons was belatedly highlighted during the 1982 Falklands conflict after the government failed to cover up their presence on ships in the naval task forces. Declassified revealed last year that British warships deployed to the South Atlantic were secretly carrying 31 nuclear depth charges.

But there have been repeated suggestions, never convincingly denied, that even more devastating weapons were deployed during the conflict.

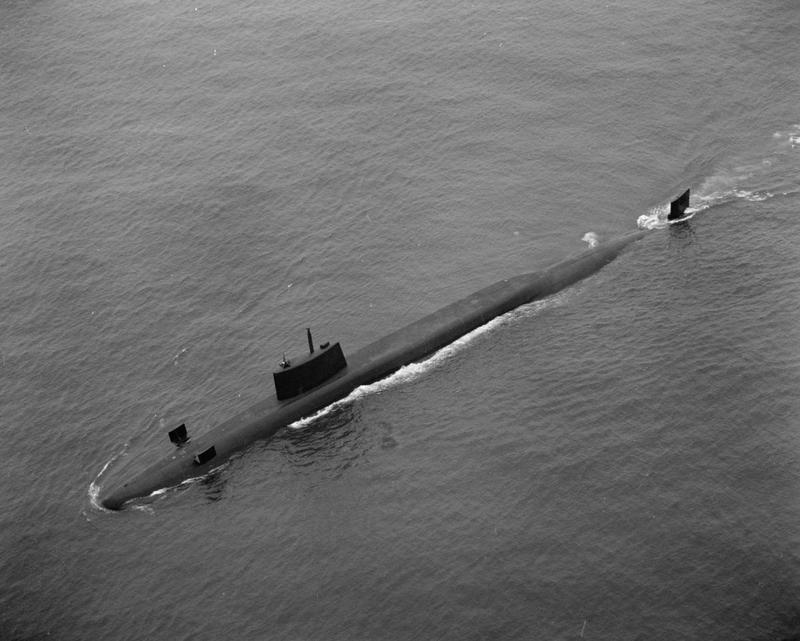

A number of sources have indicated that a submarine equipped with Polaris strategic nuclear missiles – then Britain’s major nuclear weapons system and the forerunner to the current Trident – was diverted to the South Atlantic within range of Argentina.

Polaris

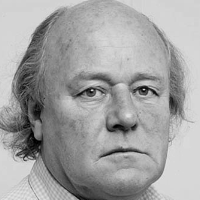

The claims were originally spelled out in a paper on “Sub Strategic Trident” by the widely respected academic, Paul Rogers, emeritus professor of peace studies at Bradford University.

Rogers, who is also an adviser to Declassified, wrote that the sources included Alan Clark MP, a senior Conservative backbencher who told fellow Old Etonian, Labour’s Tam Dalyell, at the time of the war.

Dalyell later had this confirmed to him by a senior officer in the Polaris fleet, while a third source was a senior MoD civil servant, now known to have been the late Clive Ponting, and there was also a report in the New Statesman on 24 August 1984.

Rogers wrote: “The nuclear threat might have been used if any of the task force’s capital ships – one of the carriers or the troop ship, Canberra – had been destroyed in a missile attack”.

He added: “The Polaris deployment was said to have been ordered in the wake of the sinking of the destroyer, Sheffield, after ministers had to confront the possibility that Argentine air superiority and Exocet missiles could have meant the military defeat of the task forces and the ‘political extinction of the Thatcher government’”.

The Polaris deployment would explain a severe shortage of hunter-killer submarines to form a protective screen around the task force. There were indications from MoD sources that this shortage was due to the use of nuclear-powered (but not nuclear-armed) hunter-killer submarines (SSN) to act as a protective escort to the Polaris missile submarine to cover Argentina.

“This would have been closer to Ascension Island than the Falklands but well within range of targets in northern Argentina”, Rogers wrote.

During and after the war the UK government repeatedly stated that the task force ships had a protective shield of five SSN. In early 1985, three years after the war, Rogers researched and wrote a report on SSN deployments for Dalyell, using publicly available sources.

It showed that throughout the war there were never five SSN present to protect the task force. Indeed, for a crucial period in early May, after the arrival of the task force, there were only three boats present and just one, Spartan, was fully operational.

‘Secret and personal’

Using this analysis, Dalyell shared the paper with a few colleagues and repeatedly asked questions about the deployment of a Polaris boat. That brought the issue to the attention of the government at the highest level.

A note that has recently come to light is marked “secret and personal” and was written by Sir Clive Whitmore, the top MoD official to the cabinet secretary, Sir Robert Armstrong, on 3 June 1985. It refers to a letter from “C” – the Chief of MI6, Sir Colin Figures – about Roger’s paper and the “alleged deployment” of a Polaris submarine to the South Atlantic.

The note, copied to Sir Antony Acland at the Foreign Office, was also sent by Whitmore to Thatcher’s closest adviser, Charles Powell, recommending that it be brought to Thatcher’s attention. That is hardly the kind of attention that would have been paid to Rogers’ analysis if there was nothing in the story.

Given the implications of the analysis – that the Thatcher government was prepared to threaten nuclear use against a non-nuclear state – all that would be required would be straightforward denial laced with a touch of ridicule.

Instead, Whitmore’s note said that the government had “little option but to continue with the standard line of refusing to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons at particular locations or times”.

This was to be backed up by ministerial statements that “there was no change in the standard deployment of Polaris submarines during the conflict and that the government gave a categorical assurance at the time of the conflict that nuclear weapons would not be used”.

Rogers says Whitmore’s insistence there was no change in the “standard deployment of Polaris” could be explained by the government’s decision to deploy a second Polaris submarine to the normal patrol pattern in the North Atlantic to replace the one sent further south.

An initial assurance that a nuclear weapon would not be used would not hold if the task force was in serious trouble and the UK facing possible defeat.

First use

This was all more than 40 years ago, but is still relevant today, given that the UK has maintained a nuclear posture that includes first-use of nuclear weapons since at least the 1960s.

Rogers notes that British officials told a NATO meeting in 1995 they had decided that Trident ballistic missiles could “undertake sub-strategic as well as strategic roles”.

At a hearing later that year at the International Court of Justice at the Hague on the legality of nuclear weapons, the UK’s attorney general, Nicholas Lyell, argued that nuclear weapons were not inherently indiscriminate. “Much of the writing on nuclear weapons on which these arguments rely dates from the Fifties and early Sixties”, Lyell told the court.

Lyell continued: “Modem nuclear weapons are capable of far more precise targeting and can therefore be directed against specific military targets… In some cases, such as the use of low-yield nuclear weapons against warships on the high seas or troops in sparsely populated areas, it is possible to envisage a nuclear attack which caused comparatively few civilian casualties.”

He added: “It is by no means the case that every use of nuclear weapons against a military objective would inevitably cause very great collateral civilian casualties.”

More recently and before the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Geoff Hoon, Tony Blair’s defence secretary, appeared to lower the threshold for a nuclear attack. States such as Iraq “can be absolutely confident that in the right conditions we would be willing to use our nuclear weapons”, he told the House of Commons defence committee.

He added in a later television interview: “Let me make it clear the long-standing British government policy that if our forces, if our people, were threatened by weapons of mass destruction we would reserve the right to use appropriate proportionate responses which might… might in extreme circumstances include the use of nuclear weapons”.

Hoon made it clear that he could envisage circumstances in which British nuclear weapons were used in response to chemical or biological weapons.

Asked whether Britain would only use weapons of mass destruction after an attack by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein using weapons of mass destruction, he replied: “Clearly if there were strong evidence of an imminent attack if we knew that an attack was about to occur and we could use our weapons to protect against it.”

Confusion, uncertainty

Successive British governments have deliberately used confusion – they call it uncertainty – over the circumstances in which nuclear weapons would be used to boost their argument that they are a “credible” deterrent.

It recently repeated the claim, saying: “We are deliberately ambiguous about precisely when, how, and at what scale we would use our weapons. This ensures the deterrent’s effectiveness is not undermined and complicates the calculations of a potential aggressor”.

This spurious claim of course increases the risk of an unintentional or accidental nuclear conflict. Such claims are even more dangerous at a time tactical nuclear weapons are being placed in a spotlight unprecedented since the cold war.

Putin’s deployment of tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus has been condemned by NATO. But as Daniel Hogsta, executive director of ICAN, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, has pointed out, the US stations nuclear weapons in five European countries – Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and Turkey, and now in Britain as well, it seems – and is currently modernising its arsenal.

He adds that the United States’ new B61-12 gravity bomb is a guided weapon with a yield which can be varied between 0.3 and 50 kilotons.

North Korea, meanwhile, has shown photographs of what it says are small nuclear weapons that could be fitted on short-range missiles.

Putin’s earlier implied threats to use nuclear weapons in the war in Ukraine is rightly viewed as a dangerous and destabilising position to take. It is also uncomfortably close to the UK’s position during the Falklands War over 40 years ago.