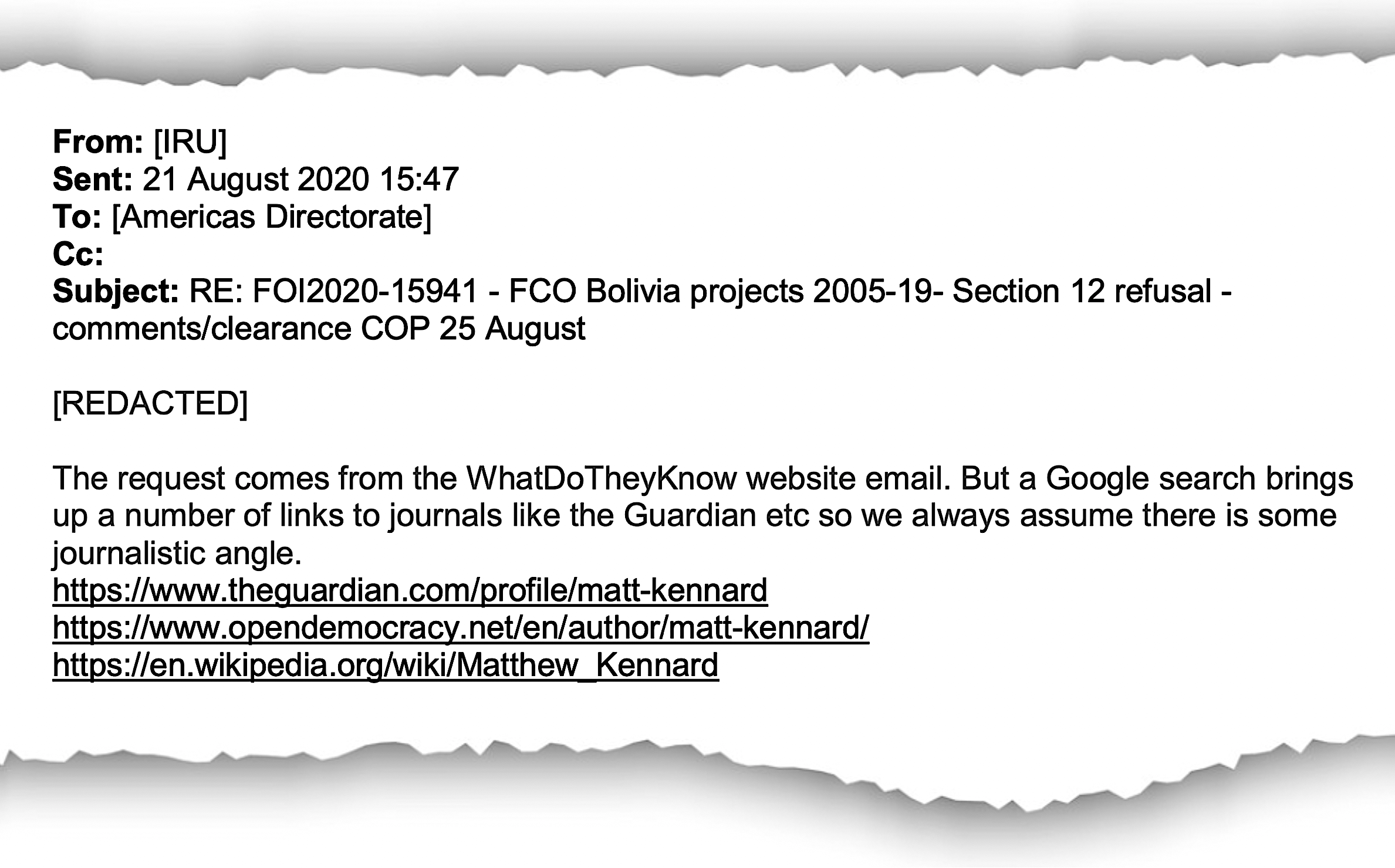

- Foreign Office staff googled Kennard and shared links to his profile pages on the Guardian, openDemocracy and Wikipedia

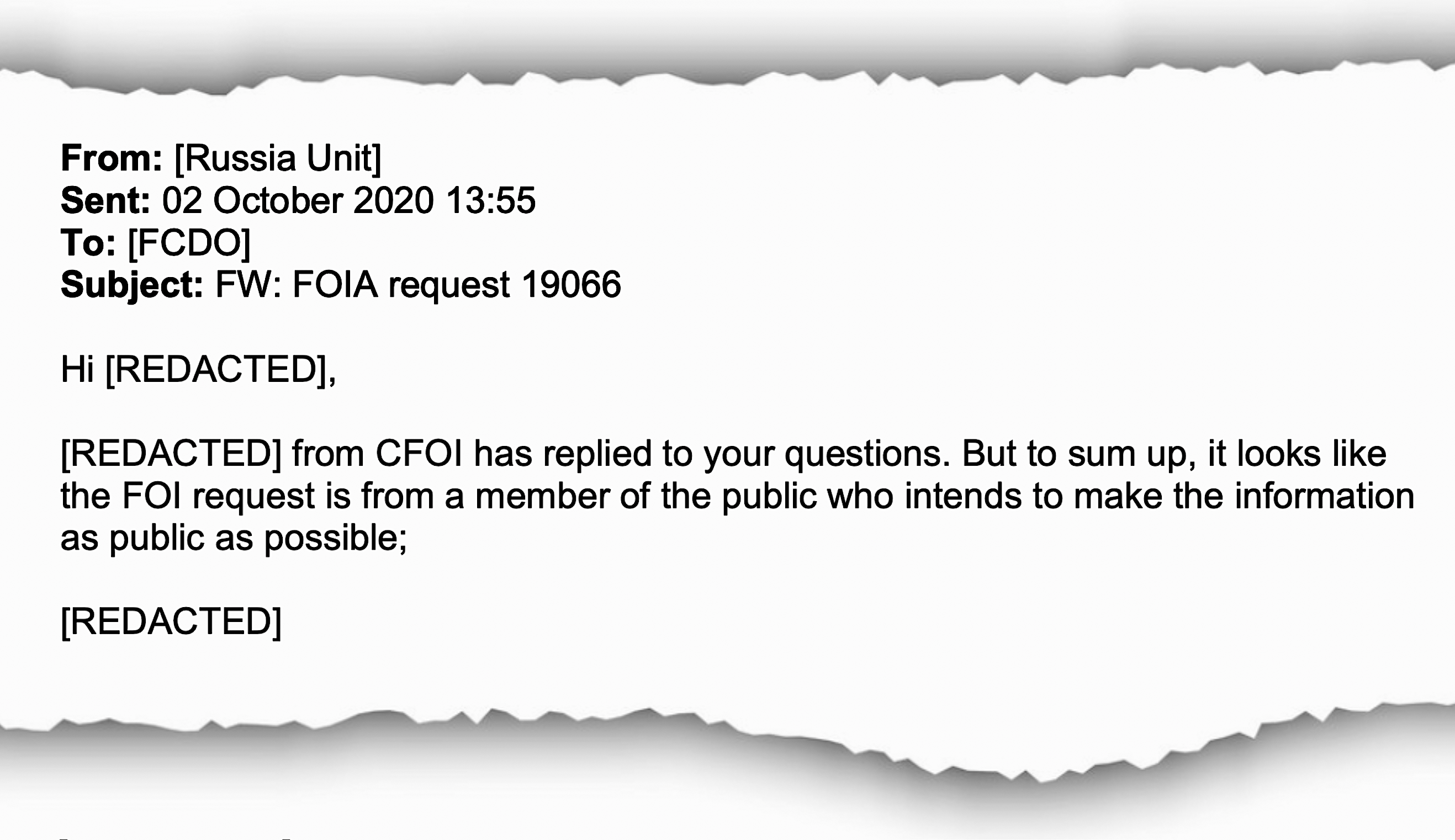

- Government official noted ‘it looks like’ Kennard ‘intends to make the information as public as possible’

- Separately, the Cabinet Office, which supports Prime Minister Boris Johnson, internally referenced Kennard 1,900 times in 18 months

Foreign Office emails obtained by Declassified show that government officials collected data on the organisation’s reporter Matt Kennard before deciding not to release information to him.

Requests made under the UK’s Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) are meant to be “applicant blind” and answered “without reference to the identity or motives of the requester”.

Kennard submitted a request in August last year for information on the Foreign Office’s programmes in the South American country of Bolivia. The first Foreign Office email discussing the request appears to answer a question from its Americas unit about Kennard’s identity.

“A Google search brings up a number of [Kennard’s] links to journals like the Guardian etc,” reads the internal email from the information rights unit, which deals with public requests.

It noted “we always assume there is some journalistic angle”, before posting links to Kennard’s profile pages at the Guardian, openDemocracy and Wikipedia websites.

Hours later, the rejection was forwarded to the Foreign Office press office with the note “Requester looks to be a journalist”. It is assumed these words are underlined because it included a hyperlink to one of Kennard’s profile pages.

Another Foreign Office email, regarding a different information request, again pointed out Kennard “appears to be a journalist”.

Tom Short, a solicitor at law firm Leigh Day specialising in human rights, told Declassified: “Everyone has a right to know about the activities of public authorities, regardless of who they are or the reason why they are seeking information. This is a core principle of holding government to account in a democratic society. Accordingly, the FOIA is clear that requests must be treated as purpose and applicant blind.”

He added: “A public authority’s focus should be on the information sought, not on who is requesting it — disclosure to a single requester is after all effectively disclosure to the world.”

‘Who is the requestor?’

Another round of background checks on Kennard was sparked by a further freedom of information request, this time regarding the then prime minister Tony Blair’s meetings with Russian leader Vladimir Putin and Syrian president Bashar al-Assad in the early 2000s.

The Foreign Office’s Russia unit emailed: “Have heard back from [British Embassy] Moscow, and they had a couple of questions on this [information request]: Who is the requestor? Is the information for internal use or for a member of the public?”

Shortly afterwards, the information rights unit replied, saying the requestor was Kennard. The Russia unit then sent an email to an unspecified Foreign Office account stating: “To sum up, it looks like the… request is from a member of the public who intends to make the information as public as possible.” The rest of the email is censored.

The Foreign Office did eventually disclose a heavily redacted copy of the briefing notes for the Putin meeting, but the notes prepared for Blair’s meetings with Assad have still not been released nine months later.

Lawyer Short said: “Where a public authority considers or highlights an applicant’s identity when handling an information request, it will almost certainly be acting unlawfully under FOIA, but may also be in breach of data protection laws as it may amount to unlawful processing of personal data.”

He added: “Handling requests in this way completely undermines the freedom of information regime and is nothing short of an attack on democratic accountability.”

‘Monitoring’

The profiling of Kennard by the UK government appears to go further than the Foreign Office. Kennard’s separate request to the Cabinet Office for information it held on him for the 18 months to March 2021 was rejected because, the government said, there was too much material to process.

The Cabinet Office, which is responsible for supporting Prime Minister Boris Johnson, said that the initial search for data relating to Kennard “returned more than 1,900 results”, an average of four mentions per day for the period in question.

The department, which is currently run by Michael Gove, a close ally of Johnson, explained the high number was “likely to be due to media article monitoring, where multiple copies of articles written by you could have been circulated in the Cabinet Office”.

However, Kennard authored just 31 stories for Declassified in this 18-month period.

The Cabinet Office took two months longer to answer the request than its statutory obligation, but then claimed that going through the 1,900 results to “extract” Kennard’s personal data would be “excessive” and rejected the request anyway.

The search did, however, highlight four cases where Kennard’s information requests had been passed to the Cabinet Office’s Clearing House, a controversial unit which deals with information requests for particularly sensitive information. The unit has been accused of “blacklisting” journalists.

A previous data request sent by Kennard, this time to GCHQ, Britain’s largest intelligence agency, showed that it had blacklisted him after he published information about the agency’s controversial schools programme.

In August 2020, Declassified discovered it was blacklisted by the Ministry of Defence press office when our staff reporter Phil Miller was told by a spokesman, “We no longer deal with your publication.”

After a Level Two press freedom alert was issued by the Council of Europe, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace reversed the blacklisting and ordered an independent review of the case.

Kennard worked as a staff reporter for the Financial Times in Washington, DC, New York and London after graduating from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

He then became director of the Centre for Investigative Journalism before co-founding Declassified UK, with Mark Curtis, in 2019. He is the author of two books investigating US military and economic policy.

Rebecca Vincent, director of international campaigns at Reporters Without Borders, told Declassified: “This apparent selective application of the Freedom of Information Act is not in keeping with the letter or spirit of the law, and is yet another worrying example of restrictions being placed on media viewed as critical.”

She added: “The UK government is obligated to act transparently and must comply with FOIA requests submitted by any journalist, or any member of the public for that matter. Such undue restrictions on freedom of information are only serving to tarnish the UK’s press freedom record.”