- ‘We are not engaging with [Matt Kennard]’, internal GCHQ email says.

- ‘Watch out watch out there’s a journo about’ is subject line of one email thread.

- GCHQ monitored Twitter account of Declassified editor, Mark Curtis, and put out internal ‘Media Alert’ for one Declassified investigation.

- Civil Service Code states: ‘You must not: act in a way that unjustifiably favours or discriminates against particular individuals or interests.’

- Reporters Without Borders calls it ‘a Trumpian move that has no place in British democracy’.

- Declassified was previously blacklisted by Ministry of Defence which has since apologised and ordered a parliamentary review.

Media organisation Declassified UK was blacklisted by Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), Britain’s signals intelligence agency, internal emails from the organisation show.

GCHQ staff said they would “not be engaging further” with Matt Kennard, Declassified’s head of investigations, and decided to “ignore” his requests for information on articles he was writing about a controversial GCHQ programme in British schools.

It is not clear if the blacklisting continues. However, the last query Kennard sent to GCHQ’s press office concerning another story, on 23 September, also received no response.

The emails are revealed in the results of a so-called subject access request which Kennard submitted to GCHQ in September to obtain any data the agency held on him.

Kennard, a former journalist at the Financial Times who co-founded Declassified last year, first approached GCHQ in September 2019 asking for details of its Cyber Schools Hub (CSH) programme, also known as CyberFirst.

In subsequent months, some basic information about the programme was provided by the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), an arm of GCHQ which manages the schools programme. However, an interview with a CSH administrator and a visit to one of the schools were refused.

Declassified published a three-part investigation in June. The articles revealed that the CSH operates in twice the number of schools as officially claimed, including primary schools, and has gained access to at least 22,000 primary and secondary school children.

GCHQ was also revealed to be secretively promoting arms companies involved in war crimes to school children.

The NCSC stopped responding to Kennard’s questions after Declassified published the first investigation, which included comments from the NCSC, on 2 June. Kennard did not receive a response to the last three emails he sent to the NCSC regarding the schools programme.

Refusing to engage with a journalist because their stories are perceived as “negative” would appear to breach the UK’s Civil Service Code, which states: ‘You must not: act in a way that unjustifiably favours or discriminates against particular individuals or interests.’

‘Watch out watch out there’s a journo about’

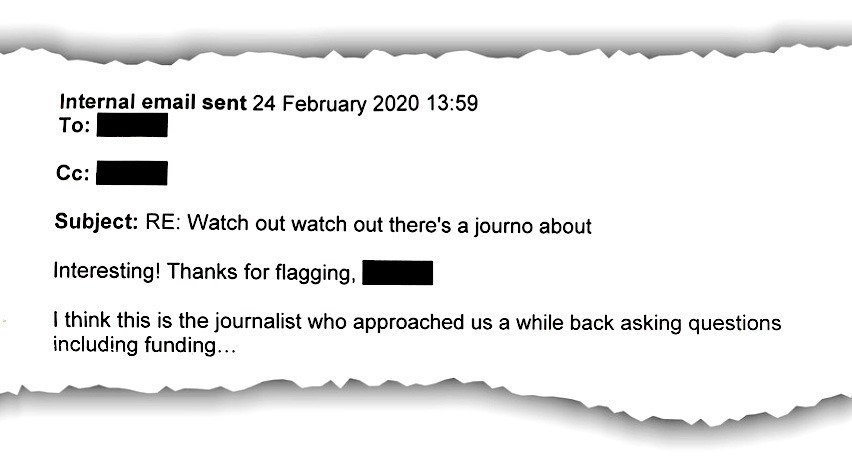

The earliest email disclosed by the subject access request shows that internal GCHQ correspondence discussing Kennard on 24 February 2020 had a subject line entitled “RE: Watch out watch out there’s a journo about”.

The last email Kennard had sent to the NCSC was on 16 October 2019, more than four months before, suggesting the February email thread was sparked by Kennard arriving in-person that day at Cleeve School, the lead “hub” in the programme which is located near Cheltenham, southwest England.

Kennard’s records show he asked the receptionist at Cleeve – a 20-minute drive from GCHQ’s headquarters in Cheltenham – for an interview at 1.22pm. The internal GCHQ email was sent just over half an hour later, at 1.59pm.

The receptionist initially promised to arrange an interview, but after making a phone call, she said all relevant staff were busy and to try later. Kennard returned later in the day and was told again that no relevant staff were available.

It is likely the school tipped off GCHQ who told them not to facilitate an interview. The only email from the thread disclosed by GCHQ reads: “Interesting! Thanks for flagging, [redacted] I think this is the journalist who approached us a while back asking questions including funding”.

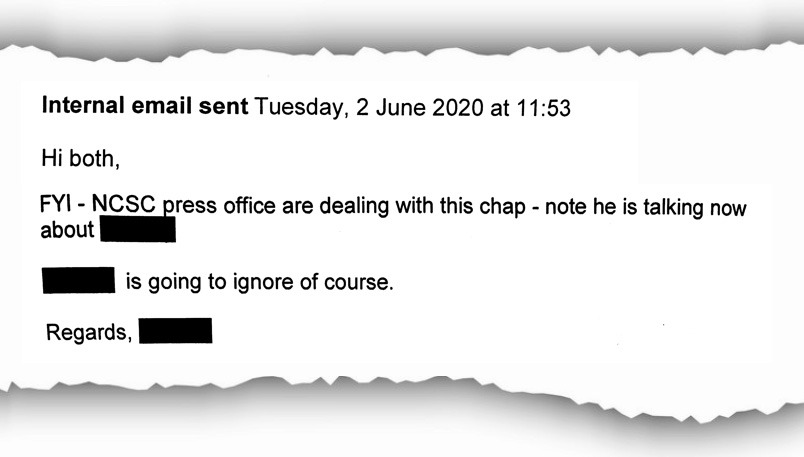

The majority of the GCHQ emails discussing Kennard date from 2 June, the day Declassified published its first investigation into the schools programme and when the blacklisting began. An email sent at 11.53am noted that “NCSC are dealing with this chap” but that “[redacted] is going to ignore of course.” It is not known which individual GCHQ was referring to.

Another email, sent at 12.04pm, contained the first reaction to the investigation published that morning. It appears to have provided a hyperlink to the Declassified article, describing it as “a negative long-read” on the CSH programme.

It added: “The article details various alleged suspicions with the initiative, claiming that it’s a vehicle for GCHQ and NCSC to spy on and recruit children. It also critically reviews materials relevant to the programme like lessons presented on courses and newsletters, with a mention of collaboration with law enforcement.”

The email continued: “The journalist has approached NCSC Comms several times over the last six months or so and seems to have a particular interest in the CSH programme. Comms has rebutted all of his claims to date, working closely with officials in this area.”

The email then noted that “the journalist is expected to publish another article on CSH/CyberFirst Schools tomorrow and this will focus on how we are working with arms dealers e.g. BAE, on this initiative.”

It concluded: “He has put the following questions to NCSC Comms and we will not be engaging further.” The email then lists Kennard’s six questions, which were not answered.

Another email, sent just over an hour later at 13.09, reiterated: “We will not be engaging further, but monitoring for further coverage and pickup.”

‘274 retweets’

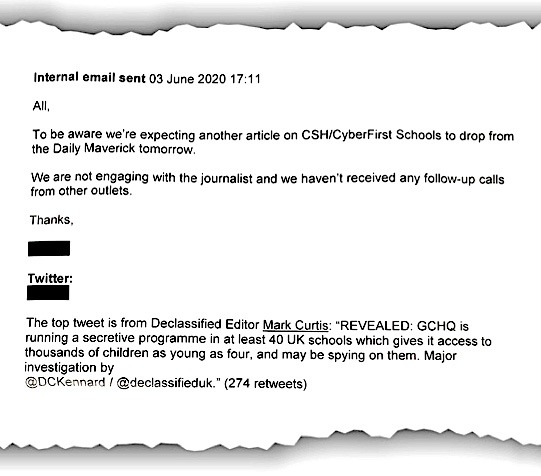

The following day, when Declassified published its second investigation – on GCHQ’s promotion of arms companies in schools – an internal email was sent at 5.11pm addressed to “All”.

This warned intelligence officers “to be aware we’re expecting another article on CSH/CyberFirst Schools to drop from the Daily Maverick tomorrow”, referring to the news site where Declassified publishes its articles.

The email again reiterated the blacklisting: “We are not engaging with the journalist and haven’t received any follow-up calls from other outlets.”

This email included an addendum with the title “Twitter” followed by a redaction. Underneath, a GCHQ officer noted that “The top tweet is from Declassified Editor Mark Curtis” and pasted the text of Curtis’ tweet from the previous day promoting Declassified’s first investigation, noting that it had received 274 retweets.

It is assumed Curtis’ name is underlined because GCHQ had included a hyperlink to direct its officers to the original tweet.

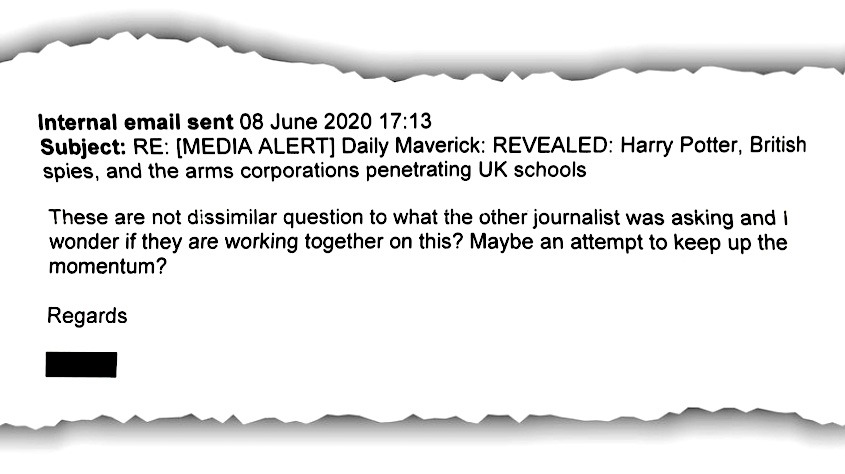

The final email disclosed by GCHQ, dating from 8 June, has the subject line: “RE: [MEDIA ALERT] Daily Maverick: REVEALED: Harry Potter, British spies, and the arms corporations penetrating UK schools”. It appears to concern a request from another journalist and asks: “I wonder if they are working together on this? Maybe an attempt to keep up the momentum?”

It is not known who these questions were from. The other emails in the “Media Alert” thread were not disclosed by GCHQ.

School secrecy

Although the CSH affects more than 20,000 British children, it has proven difficult for Kennard to get basic information from the schools themselves.

Kennard asked Cleeve School for information using the Freedom of Information Act. However, the IT teacher running the programme, Martin Peake, wrote back stating: “The information requested is exempt under section 23(1) of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 which relates to information supplied by, or relating to, bodies dealing with security matters.”

Peake added that this is “an absolute exemption and does not, therefore require the application of the public interest test in favour of disclosure”.

Kennard’s email and phone requests for interviews sent to Cleeve – and its sister “hub” Newent Community School, in Gloucestershire – were initially answered, but then ignored. As with Cleeve, Kennard eventually drove to Newent and was able to conduct an interview with the head teacher after arriving unannounced. The interview, however, was strictly off the record.

The British government has said it wants to roll out GCHQ’s schools programme – which has so far operated mainly in Gloucestershire – nationwide.

‘Destroy, deny, degrade, disrupt’

GCHQ, which takes the bulk of the £2.48-billion budgeted for the UK’s intelligence agencies in its Single Intelligence Account, is a controversial agency.

Files revealed by US whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2013 show that it had been secretly intercepting, processing and storing data concerning millions of people’s private communications, including people of no intelligence interest – in a programme named Tempora.

In 2018, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that UK laws enabling such mass surveillance were unlawful, violating rights to privacy and freedom of expression.

GCHQ has also operated offensive cyber operations against countries such as Argentina and plays a key role in UK military interventions overseas.

The British government last week announced the creation of a National Cyber Force to conduct offensive cyber operations, which will reportedly involve 3,000 staff from GCHQ, the secret intelligence service, MI6, and the Ministry of Defence.

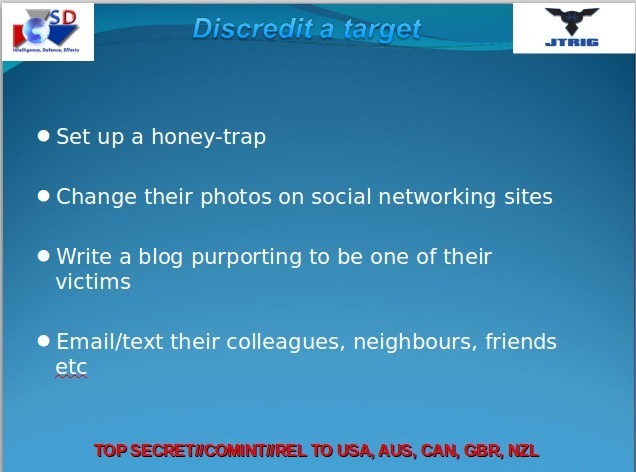

GCHQ also has a secret cyber warfare unit, named the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group (JTRIG), which takes 5% of the organisation’s budget. Its stated purpose is to “destroy, deny, degrade, disrupt” enemies by “discrediting” them, and its operations include “honey traps”, “false flags” (posing as an enemy), or “writing a blog purporting to be one of their victims”.

According to Richard J. Aldrich, a professor at Warwick University and author of the authoritative history of GCHQ, “One of the enemies on JTRIG’s list are investigative journalists who pose a ‘potential threat to security.’”

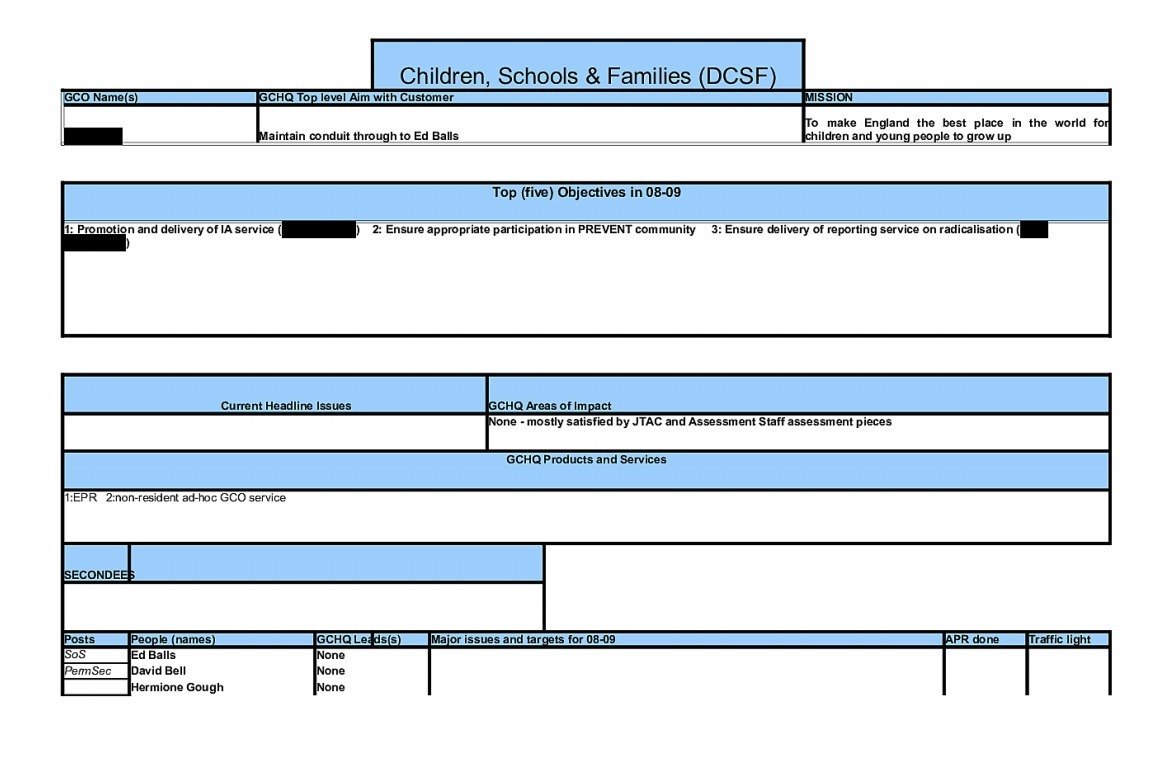

Snowden also revealed that one of GCHQ’s “top objectives” in the recent past was the “delivery of a reporting service on radicalisation” for the UK Department for Children, Schools and Families (now the Department for Education), assumed to be targeted at children in schools. It is unclear if the CSH programme is part of this “reporting service”.

The current head of GCHQ is Jeremy Fleming who joined MI5, Britain’s domestic security service, as an intelligence officer in 1993. Since being appointed director of GCHQ in 2017, he has, according to the agency, concentrated on ensuring its work is “as transparent as possible”.

Fleming was appointed by prime minister Boris Johnson, who was then foreign secretary, and now reports to Dominic Raab.

The second blacklisting

Kennard’s subject access request from GCHQ returned six internal emails, as well as two external emails sent to the NCSC, but the collection is incomplete. A number of emails are replies to threads from which no other emails have been disclosed.

The emails also only disclosed correspondence related to the first two investigations by Declassified, ignoring the third.

The third investigation, the most sensitive in the series, revealed how GCHQ’s schools programme operates in partnership with Cyber Security Associates (CSA) – a company set up by former members of the UK military’s Joint Cyber Offensive Unit, which is housed at GCHQ headquarters in Cheltenham.

Declassified revealed that CSA was teaching children how to spy on others, to hack, and launch “brute force” cyber attacks.

Kennard said: “I find it outrageous that the country’s largest intelligence agency – funded by the British public to the tune of over a billion pounds annually – just stops engaging with a journalist because it believes his stories paint GCHQ’s operations in a ‘negative’ light.”

He added: “It’s doubly worrying in this case because the programme I wanted some basic information on involves thousands of children. In a system that calls itself a democracy, we have a right to know what these types of programmes involve.”

Kennard worked as a staff reporter for the Financial Times in Washington DC, New York and London after graduating from Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in New York.

He was then Director of the Centre for Investigative Journalism, before co-founding Declassified UK, with Mark Curtis, in 2019. He is the author of two books investigating US military and economic policy.

In August, Declassified discovered it was blacklisted by the Ministry of Defence when staff reporter Phil Miller was told by a spokesman “we no longer deal with your publication”.

After a level-two press freedom alert was issued by the Council of Europe, defence secretary Ben Wallace reversed the blacklisting and ordered an independent review of the case, which is due to be published imminently.

Last week, the British government was revealed to be running a ‘Clearing House’ unit in the Cabinet Office which instructs Whitehall departments on how to respond to freedom of information requests and shares personal information about specific journalists, who it may be blacklisting.

Rebecca Vincent, director of international campaigns at Reporters Without Borders, told Declassified: “This is yet another worrying example of the UK government imposing arbitrary restrictions on media deemed to be critical – a Trumpian move that has no place in British democracy.”

Vincent added: “GCHQ and all governmental bodies must behave transparently and be open to public scrutiny in line with the UK’s commitment to freedom of information. Declassified must be able to pursue its public interest reporting unfettered.”

A spokesperson for the NCSC said: “Public engagement is at the heart of everything the NCSC does in its work to make the UK the safest place to live and work online. We carefully considered the requests from this publication, as we would with any other, and provided it with both background information and on-the-record comment.”

You can read Declassified’s three-part investigation into GCHQ’s schools programme here (1), here (2), and here (3).