Sri Lankan president Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s arrival in Glasgow on Sunday for the COP26 climate summit was met with protests from a wide coalition of Tamil activists. They claim he committed war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

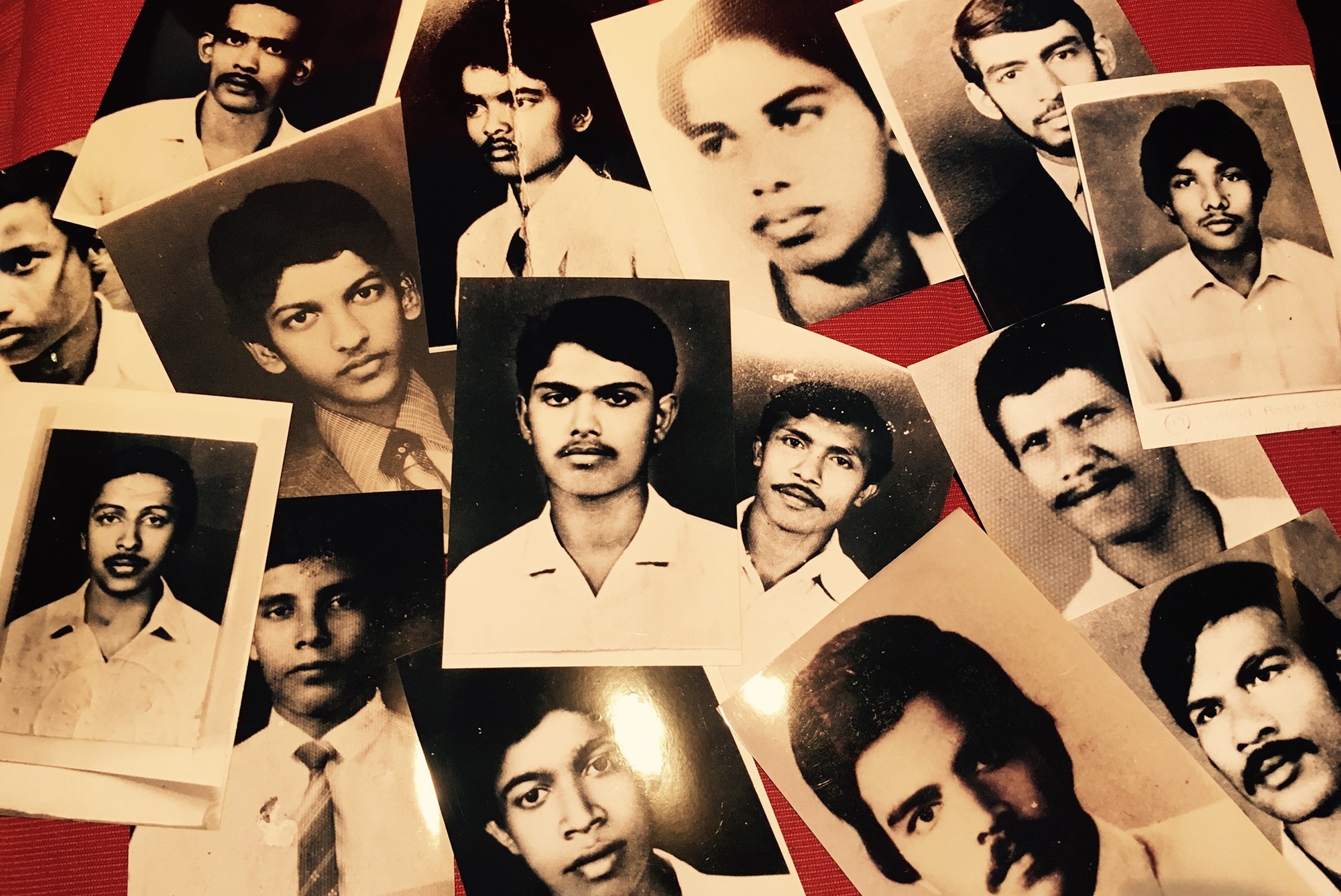

Most seriously, Rajapaksa stands accused of orchestrating the genocide of 140,000 Tamils during the end of Sri Lanka’s war in 2009. This was when he was the country’s defence secretary under the presidency of his brother, Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Sri Lanka was devastated by a brutal armed ethnic conflict that began in 1983 in which government forces fought a separatist movement, the LTTE, which sought an independent Tamil state in the north-east of the island.

During the last phase of hostilities, from January to May 2009, Rajapaksa is accused of ordering the shelling of civilians in government-designated ‘No Fire Zones’, the targeting of field hospitals, the restriction of food and medical supplies, and the apparent use of chemical weapons.

A former US ambassador has said that Gotabaya told him of his responsibility for killing Tamil leaders after they surrendered to the military in 2009. Tens of thousands of Tamil civilians surrendered to government control only to be ‘disappeared’ for 12 years and counting.

The abuses have not stopped. Since becoming president in 2019, Rajapaksa has militarised the country’s political, social, and economic spheres by rewarding ‘war-winning’ military personnel with critical roles.

The government has also completely militarised the Tamil-dominated north and east of Sri Lanka, where in some areas there is roughly one soldier for every two civilians.

The military is involved in all aspects of life in those parts of the country, and has faced years of protest from the Tamil community calling for its removal. The sheer size of the Sri Lankan military is staggering; in 2018, the World Bank estimated there were 317,000 service personnel in the country, twice the size of the UK’s regular forces.

The military has also usurped tens of thousands of acres of land on the island to establish army and navy bases, despite the war ending 12 years ago.

Trade deals

Rajapaksa is attending COP26 as a self-professed leader on issues of climate change and adaptation, especially in relation to a global compact for nitrogen reduction titled the Colombo Declaration.

However, in the background, his top officials are in the UK on a charm offensive to improve bilateral relations in efforts to secure a trade agreement with the UK. Ahead of Rajapaksa’s visit, Sri Lanka’s foreign minister, GL Peiris, met Britain’s trade secretary Liz Truss. The UK is one of Sri Lanka’s major export markets.

Britain’s post-Brexit status could present Sri Lanka with an opportunity to shirk human rights frameworks that were in place whilst the UK was in the EU, as has been evident through Sri Lanka’s failure to deliver on human rights commitments in trade agreements with the EU.

UK policy remains unclear. The Foreign Office said in July that it had not undertaken a human rights assessment of Sri Lanka’s compliance with human rights in its trade agreements. The following month, amidst political pressure, UK Asia minister Lord Ahmad said Sri Lanka will be expected to comply with human rights conventions in any trade arrangement with the UK.

But when Liz Truss met Peiris in October, she was criticised by British MPs for failing to raise human rights.

Security support

The UK is also implicated in the repressive militarisation in Sri Lanka. Police Scotland has increasingly come under fire for its long-standing training programme of police departments such as the Sri Lankan Special Task Force – an elite unit linked to torture, repression of protesters and extrajudicial killings.

This training programme has now been suspended – but not scrapped – pending a human rights risk assessment.

Rajapaksa himself received US military training when he served in the Sri Lankan army. Decades of Western support for the country’s security apparatus has done little to stop abuses against Tamils.

So instead of providing training, a tougher approach is needed. The UK must finally heed requests from victim communities, NGOs and the UN human rights council (UNHRC) for targeted sanctions on military officials implicated in war crimes and mass atrocities.

So far the British government has ignored calls for sanctions on Shavendra Silva, for example, who commanded a notorious wartime division.

In the context of this centralised, racist and militarised regime, Sri Lanka’s publicity offensive on climate-oriented programmes must be closely scrutinised for what it conceals as much as for what it promotes as climate objectives.

A sustainable path towards a climate resilient future for the island requires the structural causes of instability and ethnic conflict to first be addressed.

The UK must redouble its commitment to accountability, justice and a political solution that resolves the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka. Earlier this year, the UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, warned of further violence and ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka.

The Sri Lankan government’s intransigence on human rights and its reneging on commitments to UNHRC Resolution 30/1 – which the previous government had co-sponsored, to promote reconciliation, accountability and human rights in the country – shows that it does not intend to pursue a meaningful political solution to the ethnic conflict in the country.

The UK should leverage its bilateral relations to apply pressure on Sri Lanka to make the structural reforms required for long term stability on the island. Only when such peace and protection for human rights are achieved can there be true justice, including climate justice, in Sri Lanka.