- General Sultan bin Mohammed al-Naamani was largely responsible for a recent crackdown on demonstrators in Oman

- “The people like him who rule Oman have made it legal to steal the country’s wealth”, Omani Centre for Human Rights says

- UK authorities have failed to enquire as to how al-Naamani afforded luxury home

- Spotlight on Corruption says: “The UK must not be a safe haven for those that loot their countries or commit human rights abuses”

- The dictatorship of Oman is the UK government’s closest ally in the Gulf

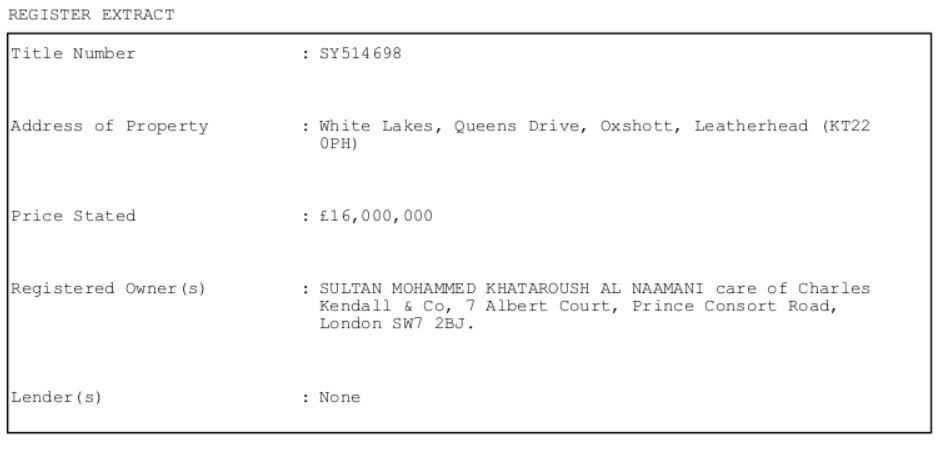

General Sultan bin Mohammed al-Naamani paid former England and Chelsea football captain John Terry £16-million for a palatial property in the UK, bagging nine bedrooms and a lake.

Now questions are being asked about how al-Naamani managed to afford the luxury home in 2014 while working as a government minister and spy chief in the repressive Gulf state of Oman.

Salaries of senior officials are not published in the secretive sultanate, whose unelected leadership is known to reward loyal aides with lavish gifts.

Last month a wave of anti-corruption protests swept Oman amid rising anger at ministers for living bloated lifestyles during an unemployment crisis.

Protesters called for al-Naamani to resign, with the Omani Centre for Human Rights claiming he is notorious for abusing his authority.

The group’s chairman Nabhan al-Hanashi told Declassified: “[al-Naamani] has so much power he doesn’t need to justify his actions — whatever he does effectively has the force of law and he cannot be held accountable. The people like him who rule Oman have made it legal to steal the country’s wealth.”

Another activist, speaking on condition of anonymity for safety reasons, said: “All state institutions are run by a mafia gang. They eat the cake and keep the crumbs for us. Corruption is everywhere.”

In a particular challenge to al-Naamani, crowds of Omanis gathered one night in the town of Bidiya near to where he is believed to own a holiday villa, bearing placards and chanting for an end to corruption.

They were met with lines of armoured vehicles and platoons of riot police in an intimidating show of force. In other towns and cities across Oman, police fired British-made tear gas and scores of activists were snatched from the streets.

Authorities are yet to admit the total number of arrests.

al-Naamani was largely responsible for the crackdown on demonstrators as he runs Oman’s security and intelligence agencies through his role as Royal Office minister.

Former UK foreign minister Alan Duncan has described Oman’s Royal Office as “vaguely similar” to MI6.

It is understood to control Oman’s external and domestic intelligence agencies, making al-Naamani ultimately responsible for the interrogation of detainees by the country’s fearsome Internal Security Service (ISS).

Multiple sources have told Declassified that detainees were not released from custody by the ISS until they signed documents promising never to speak out again.

An activist who criticised the regime on social media told us: “The ISS called me to a police station and forced me to sign a pledge while I was being coerced and threatened.”

One protester, Ibrahim al-Balushi, went on hunger strike while he was held for a week in police custody last month.

Another man, Mushaal al-Mammari says he was held for three days in solitary confinement, subjected to sleep deprivation and interrogated for hours, before being referred to the prosecutor on charges that include participating in the protests and messages found on his WhatsApp.

Perk of the job

Al-Naamani became Oman’s spy chief in 2011, when he was appointed as Royal Office minister by Sultan Qaboos in the wake of Arab Spring protests.

After he took charge, the Gulf Centre for Human Rights accused the ISS of torturing activists.

Among them was Khalfan al-Badwawi, who criticised the regime for spending money flying horses from Oman to Queen Elizabeth’s diamond jubilee pageant at Windsor Castle in 2012.

Khalfan was charged with “insulting the Sultan” and held in solitary confinement for a month by the ISS who subjected him to constant bright lights, loud music and extreme temperatures, driving him to attempt suicide.

He was later released and claimed asylum in the UK in January 2014.

That same month, al-Naamani bought John Terry’s White Lakes mansion in Oxshott, Surrey for £16-million or 8.7 million Omani rials.

According to the World Bank, it would take the average Omani around 1,600 years to earn that much money.

Oman’s authorities do not publish al-Naamani’s salary, other than to say he shares an annual pot of 18.9 million rials (£34.8-million) with 25 other ministers, several of whom are relatives of the Sultan.

Media reports from 2014 describe al-Naamani as purchasing the property on behalf of Oman’s then absolute ruler, Sultan Qaboos. The Sun claimed: “The Omani royal family wanted the house at any cost.”

“The Sultan’s most trusted aide just waltzed in and made an amazing offer” to John Terry, who profited by £10-million from the sale. There is no suggestion that Terry was aware or ought to have been aware of the source of the funds used to purchase the property.

When Qaboos died last year after half a century in power, al-Naamani carried his coffin and announced on state TV who would succeed him.

However, the property does not appear to have been passed on to the new Sultan, Qaboos’ cousin Haitham.

Land registry records show al-Naamani remains and has always been the sole owner of the property, suggesting it belonged to him outright since the original purchase in 2014.

When Declassified visited White Lakes earlier this month we saw a chef carrying a pet dog and greeting delivery drivers, including a luxury food caterer who apparently receives monthly orders.

Staff at the property confirmed White Lakes is owned by al-Naamani, but said he was in Oman and unavailable for an interview about the corruption allegations or human rights abuses.

A hand-delivered letter setting out our questions has gone unanswered.

Under so-called McMafia orders, UK authorities can require foreign officials or “politically exposed persons” to explain how they afforded luxury homes in England. Those unable to satisfy such enquiries risk having their property confiscated.

Yet so far prosecutors have only served unexplained wealth orders against a handful of individuals and there is likely to be strong resistance from the Foreign Office if such measures were ever considered against a close British ally like al-Naamani.

He has frequent meetings with senior UK officials such as defence secretary Ben Wallace and head of the military General Nick Carter.

A spokesperson from Spotlight on Corruption told Declassified: “The UK must not be a safe haven for those that loot their countries or commit human rights abuses. This requires an urgent investigation by UK law enforcement authorities, and underlines the need for a review into the weaknesses of the UK’s unexplained wealth order regime.”

Haves and have nots

Oman’s elite is widely suspected of squandering the country’s dwindling oil wealth on lavish properties abroad.

The issue is set to become increasingly politically charged as electricity and water subsidies are slashed under austerity measures designed to reduce Oman’s national debt, which has soared to 81% of GDP.

The deficit is exacerbated by a vast military budget — much of it spent on British arms — which takes up 27% of Oman’s public expenditure and costs nearly four times as much as subsidies, according to accountancy firm KPMG.

In April, Oman’s government introduced a 5% sales tax in a bid to diversify from oil revenues and balance the books. It plans to be the first Gulf state to charge citizens an income tax, a move which could fuel demands for greater political representation.

All political parties are banned in Oman and elections are only held for carefully vetted independent candidates to sit on a powerless advisory council.

Journalists have been jailed for covering corruption and the country’s sole independent newspaper, Al Zaman, was shut down — in a move some activists blame on al-Naamani.

Through its £10-million Gulf Strategy Fund, the UK Foreign Office is supporting the Omani regime on economic reforms, “crisis management” and riot police training, which was provided as recently as February by officers from Northern Ireland.

Defence minister James Heappey has said there are approximately 230 UK military personnel based in Oman — of which around 90 are on loan to the Sultan’s forces — and that they are in “regular contact with the Omani authorities…to share ideas and experience on all aspects of security including response to protests”.

The UK is also believed to operate three secret intelligence bases in Oman, which it has never officially acknowledged.