In the late 1970s, a mystery man called Timothy Landon acquired the village of Faccombe, a secluded spot in Hampshire. Instead of accumulating his wealth through business or trade, he had assembled his property portfolio from altogether more dubious activities.

Known locally as “The Brigadier” in a reference to his shadowy military past, Landon had been posted to the Gulf protectorate of Oman as a British Army intelligence officer in 1965. There, he was tasked with suppressing armed rebellion in Dhufar, an area in the southern highlands bordering Yemen.

An autonomous movement of Dhufaris had established the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf, inspired by Arab nationalist leaders in Egypt and Yemen.

Whereas the Sultan had simply asked the RAF to bomb wells and other lifelines, Landon pursued a form of counterinsurgency based on a divide-and-rule strategy trialled in other British colonial settings, exploiting splits between tribal leaders and rewarding traitors with financial payments.

At that time, Oman was virtually controlled by the UK government and the ruler, Sultan Said Bin Taymur, received more than half his income directly from London.

When Omani oil production started in 1967 the country began to generate significant income of its own, but it appears that the autocratic Sultan fell out with the British government over interests in the country’s oil reserves. The cosy friendship became unsustainable and plans were made for a coup.

Right time, right place

When Landon was moved to Muscat to investigate, the unwitting Sultan appointed him as minder to his son Qaboos; the two had met at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, a few years earlier and it is not hard to imagine that Landon had protected Qaboos from the routine bullying meted out to non-British recruits there.

But the young heir’s life had not been a lot of fun once he returned home either. After completing his military training with the British Army in Germany, Qaboos studied local government in England and embarked on a global cultural tour.

He came back to Oman in 1964 but was placed under virtual house arrest by his father who was wary of plots to usurp him. As it turned out he was right to have worried.

In 1970, Landon, who by then had earned the title of Brigadier in the Omani Army, supported Qaboos as he took control of the kingdom, ousting his father Said in an almost bloodless coup. Landon then stayed on as adviser to the young Sultan as he set about modernising the country.

Receipts from oil sales boomed. But Oman’s treasury was treated as if it were the Sultan’s personal wealth. Leaked financial files reveal that in the years immediately after the coup, Qaboos opened a series of Swiss bank accounts. He stashed away £142 million with Credit Suisse and deposited £33 million with HSBC.

Such opaque arrangements suited Landon. John Beasant, who was expelled from Oman for writing a book criticising Qaboos, said Landon was “able to make huge amounts of money through the arms deals he brokered on behalf of the Sultan.”

This would have included clandestinely dispensing oil from Oman to selected allies. According to an obituary, “as Ian Smith’s internationally ostracized Rhodesian state struggled to withstand international sanctions and a bloody bush war, Brigadier Landon lent the white-minority ruler a helping hand in the form of Omani oil. He similarly helped South Africa’s apartheid regime”.

Putting down roots

In 1977 Tim Landon married Katalina Esterházy de Galantha, a wealthy aristocrat from Hungary’s House of Esterházy. A couple of years later he returned to his new base on the Faccombe Estate, retaining his connections with the Omani Embassy in London.

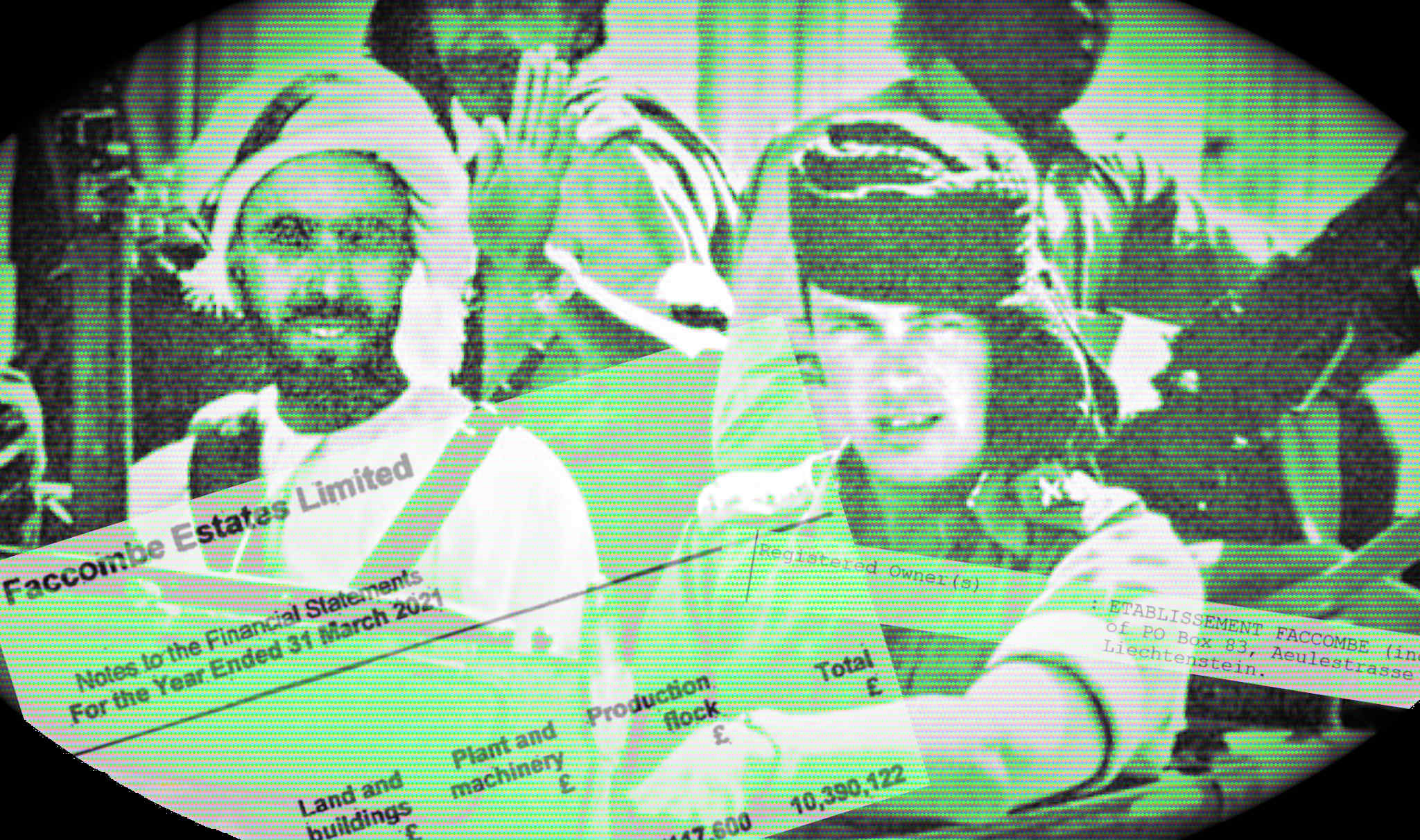

A company, the Etablissement Faccombe, was set up in the opaque jurisdiction of Liechtenstein, and registered as the owner of the Faccombe Manor estate.

Landon continued to travel to Oman until he died, using the airport at Farnborough, Hampshire, as a base for his personal jet. At home he employed a firm of security guards to protect his person and his property.

Landon was richly rewarded for his loyalty to the sultan; it was widely reported that Qaboos regularly sent him a cheque for £1 million on his birthday. As a result he became one of the largest landowners in Britain.

The 4000-acre estate at Faccombe, where he installed one of the country’s first wind turbines, is worth between £5 and £10 million. In addition, he owned swathes of grouse moors in the north of England and Scotland.

That wealth, augmented by other property and real estate investments in Europe and America, mineral exploration and farming in Africa and more, didn’t save the Brigadier from dying of cancer in 2007 at the age of sixty-four, but he left a son, Arthur, who, in 2008, was the youngest person to feature in the Sunday Times Rich List.

Arthur Landon was a close friend of the Princes William and Harry who often took part in his partridge and pheasant shooting facilities at Faccombe. These are now outsourced to the Ian Coley Sporting Agency, whose Gun Shop houses one of the largest selections of new and used shotguns in the UK, “with around 1000 guns in stock at any one time, including over 25 pairs of guns and many left-handed guns”.

In 2018, the Jack Russell Inn, part of the Faccombe estate, hosted Harry’s stag event, and the pub’s restaurant reached the finals of the Eat Game Awards the following year.

Build the wall

Roly Clarke, a retired steelfixer, helped construct the security wall around the Brigadier’s estate in the early 1980s.

He had been employed at countless high security sites across southern England, from the underground nuclear shelter at Aldermaston to the government military research facility at Porton Down and the RAF testing centre at Boscombe Down on Salisbury Plain. He had also taken part in the construction of the synchrotron at the Harwell science and innovation park in Oxfordshire.

In this case, the wall around Landon’s house and garden was reinforced with dense steel cages covered with concrete and then given a traditional brick and flint veneer. There was a full-time security operation posted around the house and the whole place was wired with motion detectors.

On one occasion Roly was walking along a path at the back of the house with the head gardener, and “all of a sudden three blokes jumped out and confronted us — we had gone through one of their security beams. That was in the daylight, not dusk or anything.”

When the guards discovered who they were they let them go on their way, but it was evidently quite a shock. The surveillance inside the house was intense as well, with cameras in every room and along corridors, and guards monitoring the screens around the clock.

Another sign that Landon might have found it hard to sleep at night was that the landlord of the village pub — the same Jack Russell Inn where Prince Harry would one day have his stag night — was instructed to alert security every time a stranger turned up.

On several occasions Roly witnessed Landon’s dramatic arrival at the estate. Flanked by guards on motorbikes, two black Range Rovers with darkened windows sped up the road and shot through the gates.

Landon is believed to have hired his bodyguards from Saladin Security, who had trained the Sultan’s Special Forces in Oman. Saladin’s predecessor firm, Keenie Meenie Services (KMS), included Landon as one of its unofficial directors.

The Metropolitan police’s war crimes unit is currently investigating the activities of KMS mercenaries in Sri Lanka during the 1980s.

Return of a Native: Learning from the Land is available from Repeater Books for £16.99.