The UK Foreign Office conducted covert propaganda operations inside the UK during the Cold War, recently declassified files show.

It sought to challenge and discredit leading journalists at television’s World In Action programme, intellectuals such as Eric Hobsbawm and the leaders of some of Britain’s largest trade unions.

The government body responsible was a highly secretive unit called the Home Desk, a part of Britain’s Cold War propaganda arm, the Information Research Department (IRD), which was housed within the Foreign Office.

The Home Desk’s modus operandi was to collect information on “subversive” individuals and organisations from open and secret sources, ranging from newspaper clippings and books to MI5 moles and classified material.

It would then pass this information to trusted contacts in the British press, parliament, think tanks, universities, and other private networks in an effort to discredit the activities of “subversive” leftists in Britain.

The Home Desk was kept entirely hidden from the public, and its funding was not subject to parliamentary oversight. Outside of a small clique of high-ranking British ministers, diplomats, and intelligence agents, the Home Desk simply did not exist.

Its ultimate target was the British public. The recently declassified record allows us to peel back a layer of these secret operations.

The Home Desk

The IRD was established in 1948 as a secret, anti-communist propaganda unit whose role was to collect information about communist movements, and distribute this material to key figures all over the world. The objective was to build resilience against communism, and cultivate foreign agents of influence.

The IRD also planned and executed covert counter-measures, involving placing articles in the press, financing publishing houses and magazines, disseminating forged documents, and encouraging political agitators in foreign states.

During the late 1940s, Clement Attlee’s Labour government began to view communist subversion as a dual international and domestic concern.

In 1951, a secret group named the Anti-Communist (Home) Committee was established, comprising representatives from the Foreign Office, Treasury, Home Office, Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Labour, and Security Service (MI5).

Chaired by cabinet secretary Norman Brook, the committee’s objective was “to keep communist activities in this country under review and to recommend what counter-action could properly be taken”.

In June of that year, the committee recommended that a “Home Desk” should be “added to the Information Research Department… to act as the focus for the collation and dissemination of intelligence about communist activities on the home front”.

‘Passing information to the right people’

The Home Desk was thus born as “an extension on to British soil of what [the] Information Research Department was trying to do globally”. This involved “passing information to the right people in the right way at the right time”.

The Anti-Communist (Home) Committee met five times in 1951, four times in 1952, and then roughly twice a year until 1963, at which time it was renamed the Official Committee on Communism (Home).

“When the minutes of a Home Regional Meeting are issued, the recipients destroy the minutes of the previous meeting”

Throughout this time, the IRD chaired a sub-committee named the Home Regional Meeting. It was attended by representatives from the Foreign Office, MI5 and Ministry of Labour, and functioned as a forum for discussing the Home Desk’s operations and other domestic counter-subversion activities.

The Home Regional Meeting convened 104 times between 1952 and 1963, yet it never “had any official existence” until years later.

Indeed, it was a highly secretive affair. “We have a rule that when the minutes of a Home Regional Meeting are issued, the recipients destroy the minutes of the previous meeting”, newcomers were instructed.

Targeting television

One set of targets the Home Desk identified were journalists working for World in Action, Granada Television’s flagship investigation series which ran from the 1960s to the 1990s.

The programme broke a number of high-profile and damning stories about the British state. It also led a campaign which resulted in the release of the Birmingham Six, a group of Irish men who were falsely accused of orchestrating the Birmingham pub bombings in 1974, and sentenced to life in prison.

“World in Action is a highly suspect organisation”, one IRD official complained. It was among a number of outlets to publish stories that were “anti-police, anti-immigration policy, pro-PIRA [referring to the Provisional Irish Republican Army] etc. or… guilty of gross distortion”.

In 1976, the Home Desk prepared a “bout de papier” (literally, scrap of paper) on Gavin MacFadyen, an American journalist at World in Action who had moved to Britain during the 1960s. It noted his “recent activities as leader of a ‘World in Action’ team in Hong Kong, where it was investigating child labour in the toy industry”.

MacFadyen was said to be tainted by “political bias” and seen to be using “questionable investigative methods”. This was “only the latest example of a number of occasions when Trotskyists or other extremists connected with this programme have given cause for concern”, it was noted.

As events unfolded, the IRD became increasingly interested in taking counter-measures against MacFadyen and his colleagues, Gus MacDonald and David Boulton. IRD chief Ray Whitney, for instance, noted that “we are… attracted to the idea of taking counter-action against ‘World in Action’”.

“World in Action is a highly suspect organisation”

With this in mind, the IRD collaborated with a “highly delicate source” in Hong Kong – then still a British-controlled territory – who fed sensitive information about the journalists’ activities to the Foreign Office.

By compiling information on the World in Action team, the IRD planned to inspire a “hatchet job” on the journalists. This would take the shape of a “feature article” in the British press which would be based on a “crime-sheet of errors” regarding “how ‘World in Action’ operate”.

One Foreign Office official even recommended that “we might try to stop the broadcast of the programme” altogether, with another deliberating an approach to Sir Paul Bryan, an MP and director of Granada Television.

The IRD’s “hatchet job” on World in Action did not ultimately transpire, but not due to reticence about targeting a domestic media organisation.

Whitney was worried that such an attack could play “into the hands of the ‘World in Action’ Trotskyists”, he claimed. It could do this “by illustrating the extent to which… they have succeeded in raising sensitive issues”, and might also “stimulate increased public interest in the programme”.

The IRD chief nonetheless advised that the IRD could “add these papers to the dossier which has been accumulated on ‘World in Action’ over the years in the hope that there will be an opportunity in the future to use this material more effectively”.

MacFadyen went on to found the Centre for Investigative Journalism in London, before passing away in 2016.

Eric Hobsbawm

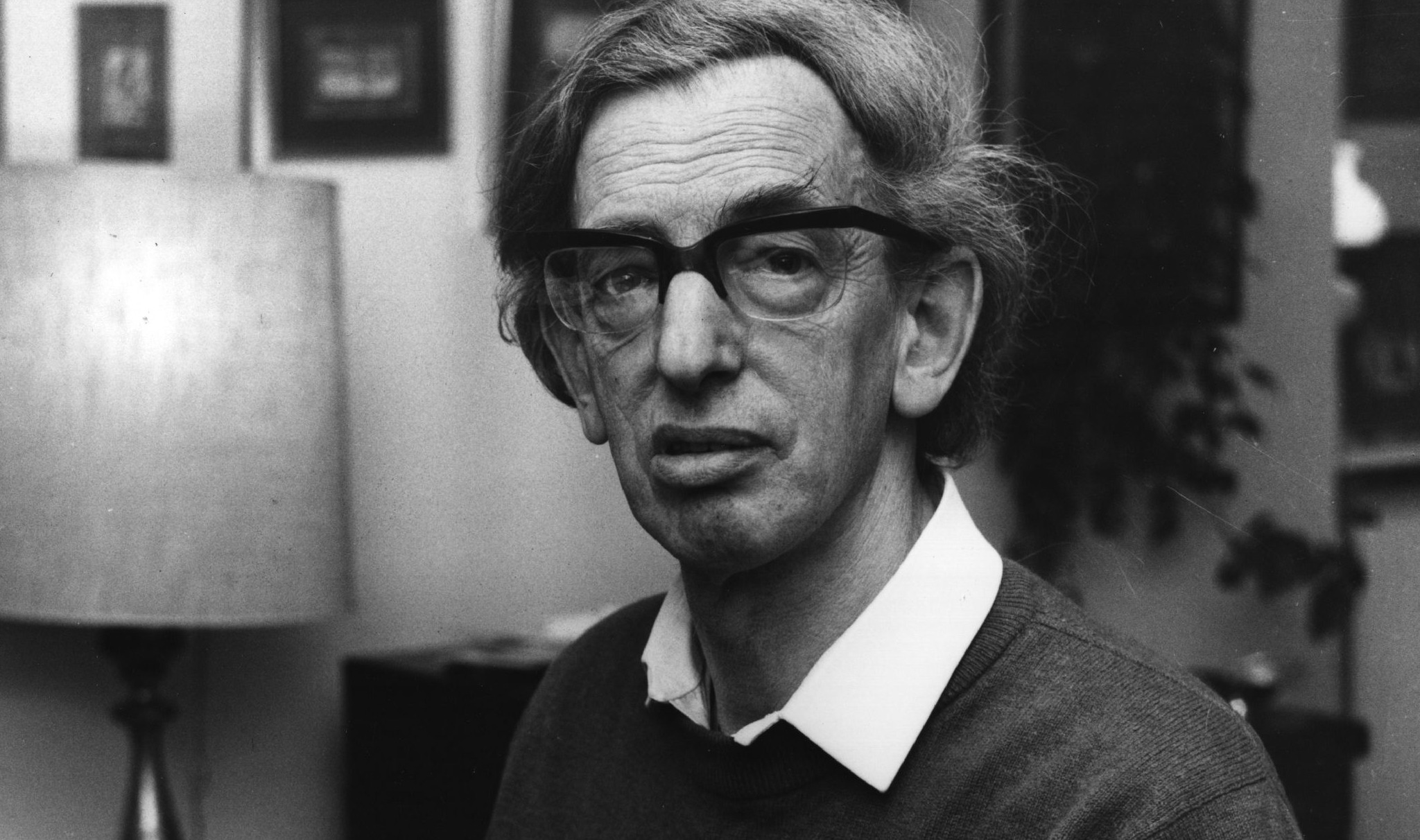

Another remarkable episode in Britain’s domestic counter-subversion campaign concerns Eric Hobsbawm, a renowned Marxist intellectual who was described in one obituary as “arguably Britain’s most respected historian of any kind”.

It shows how the Foreign Office used a private network of journalists and academics to target him and delegitimise the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB). It also demonstrates how the UK government capitalised on the declassification of official files to launder strategically valuable information through supposedly independent media organisations.

In 1973, Hobsbawm published Revolutionaries, a series of essays about revolutionary parties, movements and writers across the globe.

The IRD viewed the publication of the book as a useful “peg” with which to attack Hobsbawm and his views on the CPGB’s actions in the lead-up to the second world war.

Hobsbawm’s contention that “there is something heroic about the British and French Communist Parties in September 1939” was seen as particularly offensive, and counter-measures were drawn up.

In August 1973, then IRD chief Thomas Barker approached Lord Chalfont, a British journalist and former defence minister, with a plan to hit back at the historian. “The whole conversation would have to be strictly unattributable”, Chalfont was repeatedly told.

“The whole conversation would have to be strictly unattributable”

The idea was for Chalfont to publish an article in The Times refuting Hobsbawm’s claims, and arguing that the CPGB’s actions in the run-up to the second world war had been little more than cowardly.

Remarkably, most of the article had already been written for Chalfont by the IRD. Chalfont merely needed to sign his name to it, and send it to The Times for publication.

Barker also provided Chalfont with a photocopy of a declassified War Cabinet paper on the subject of the CPGB’s conduct before the second world war, alongside a summary of the supporting documents, a copy of Hobsbawm’s book, and press cuttings. The supporting documents were based on classified information, and were for “background use” only.

Chalfont declared that he was “much attracted by the prospect of writing an article or series of articles for The Times on this theme”, but changed his mind shortly afterwards.

MI5’s monitoring of prominent academics like Hobsbawm has been explored further in academic William Styles’ PhD thesis, published in 2016.

‘The Security Service are very pleased’

The IRD then moved on to British-American historian Robert Conquest, “an old departmental contact and former Foreign Office official”, to whom it passed on much of the same material. Conquest promised to “see if he, or discreetly any of his friends, can use it”.

In October 1975, an article appeared in the Daily Telegraph by Donald Cameron Watt, a distinguished professor of international history at the London School of Economics. The article was largely based on the information passed by the IRD to Conquest.

MI5 and the Home Desk viewed this as a successful operation.

“The Security Service are very pleased and will inform us of reactions”, noted IRD official J.E. Tyrer. “So far the Morning Star has ignored the piece, but, now that attention has been drawn to these papers in the Public Record Office, the controversy (not least inside the [Communist] party) arising from these disclosures is likely to simmer gently for some time”.

The Home Desk also sent the War Cabinet document to Ghita Ionescu, a professor at Manchester University, alongside a pre-written letter to The Times condemning the CPGB’s historical revisionism with regards to the second world war.

“A characteristic common to dictatorships, whether of right or left, is the need to distort and suppress uncomfortable and discreditable facts”, the pre-written letter noted, with no apparent sense of irony.

Ionescu was encouraged to attach his name to the letter, and send it to The Times for publication. “I enclose a suggested draft letter to The Times on the subject”, wrote Tyrer. “Perhaps you could tell [Foreign Office official] Mervyn [Jones] when he gets in touch with you on Monday how it strikes you?”.

‘The charge of conspiracy’

In collaboration with MI5, the Home Desk also kept “a watch on communist activities in the trade unions” throughout the Cold War.

During the late 1940s and 1950s, the CPGB enjoyed strong representation within the Electrical Trades Union (ETU).

“At one point”, wrote trade unionist Jim Harte in Tribune, the CPGB “could boast of having an ETU general secretary and a general president as loyal members, bucking a national movement which saw communists banned from holding office in British trade unions”.

After elections in 1959, the ETU was rocked by allegations of ballot rigging against general secretary Frank Haxell and 14 others, and was taken to court by trade unionists Jock Byrne and Frank Chapple.

The recently declassified files show that the Home Desk secretly inspired the allegations against Haxell and his colleagues, thereby prompting the legal challenge and paving the way for the ETU’s take-over by more right-wing elements.

“Our main asset at present is the charge of conspiracy against the ETU. This is itself a product of our action”, reads an IRD file from 1961 which is marked Top Secret.

As the legal case proceeded, the Home Desk conducted “discreet publicity action” regarding the ETU and planned to encourage “questions of measures to reform or control more closely election procedures in the [British] unions”.

Once the legal case had concluded, communists were barred from holding elected positions in the union.

Exposing strike leaders

Haxell was far from the only ETU member pinpointed by the Home Desk. The files show how it worked with MI5 to target leading British trade unionists and interfere in trade union elections.

In 1963, the IRD and MI5 were “charged with the task of… exposing the leading members of the strike committee” in the ETU, “especially the communist electrician Charles Doyle and the communist engineer George Wake”.

“The Home Desk worked with MI5 to target leading British trade unionists”

The Home Desk subsequently boasted that the Daily Mirror had executed “a most effective exposure” of Doyle and Wake, “partly on the basis of its own information”, and partly on information provided by the Home Desk itself. Doyle was subsequently expelled from the ETU.

Many of these operations were conducted in association with the Industrial Research and Information Service (IRIS), an anti-communist trade union organisation which received covert funding from the British state.

In 1968, one IRD official noted how IRIS “played a major part in the past decade in effecting the defeat of communists in various key elections in a number of unions.”

These included the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) presidential election of 1959, the Yorkshire NUM elections of 1960, and the Amalgamated Union of Foundry Workers general secretary election of 1967.

‘The operations were successful’

The 1950s and early 1960s were a high point in the Home Desk’s activities. “The operations were successful; intelligence was successfully ‘marketed’, and non-official publicists and organisations were discreetly enlisted”, noted Norman Reddaway, a seasoned British propagandist.

After Harold Wilson’s Labour Party was elected in 1964, the Home Desk seemingly operated at a slower rate.

Wilson had “always been uneasy about the activities of this [Home] Desk”, it was noted, given he felt an IRD associate had made an “unfortunate intervention” during the 1964 election. By 1970, the Home Desk’s “volume of operations had dwindled to modest responsive work to meet a few requests from old clients”.

Nonetheless, the Home Desk continued in operation, and the Official Committee on Communism (Home) was renamed to the Official Committee on Subversion (Home) in 1968 to reflect the “other subversive fields [emerging] such as Trotskyism, Anarchism, ‘Protest’ and even violent Welsh extremism”.

After the Conservative Party won the 1970 election, prime minister Edward Heath “showed new interest in stepping up this work”.

This was partly to counter “the systematic provision to militant Unions of meticulous briefs on how to extract the last ounce of flesh from the employers and the country”. New life was thus breathed into the Home Desk, with heightened levels of coordination between Downing Street, the IRD and MI5.

In 1977, after the Labour Party had returned to power, the IRD was shut down. Britain’s domestic counter-subversive machinery, however, did not disappear with it.

The Foreign Office continued to conduct IRD-type activities through a covert arm named the Special Production Unit (SPU), while MI5 remained wholly intact.