The UK’s secret intelligence service, MI6, worked with the CIA to provide a list of alleged Soviet agents in Iran to Ayatollah Khomeini’s theocratic regime, which took power after the overthrow of the UK-backed Shah in 1979. The information was used by the regime to execute leading members of the Iranian communist party, the Tudeh.

The British files also highlight how at least one Foreign Office official considered how the UK might benefit from the forced confessions given by Tudeh members at the time, which were believed to be extracted under torture.

The files suggest British policy was motivated by the desire to curry favour with Iran’s new rulers, rather than concerns over Cold War geopolitics or Soviet influence in Iran, which was recognised to be minimal.

The hit list

The list of Iranians allegedly working for the Soviet Union in Iran was provided to Britain by Vladimir Kuzichkin, a major in the KGB who defected to the UK in June 1982, as reported by the New York Times and London Times in 1986. The information gleaned by MI6 from Kuzichkin – who was responsible for maintaining contacts with the Tudeh party, the main leftist organisation in Iran established in the 1940s – was also shared with the CIA, and passed on to Tehran.

The Iranian regime proceeded to round up over 1,000 members of the Tudeh party and eventually executed as many as 200. The party was banned and forced underground.

Britain’s senior official in Iran at that time, Nicholas Barrington, states in his memoir that Kuzichkin’s information simply “found its way” to the Iranian authorities after the Russian’s defection, without specifying the British role.

Files from the time – when Barrington was head of the British Interests Section in Tehran since Iran and the UK had cut full diplomatic relations – suggest that British officials supported Iran’s repression of the Tudeh.

‘A significant step’

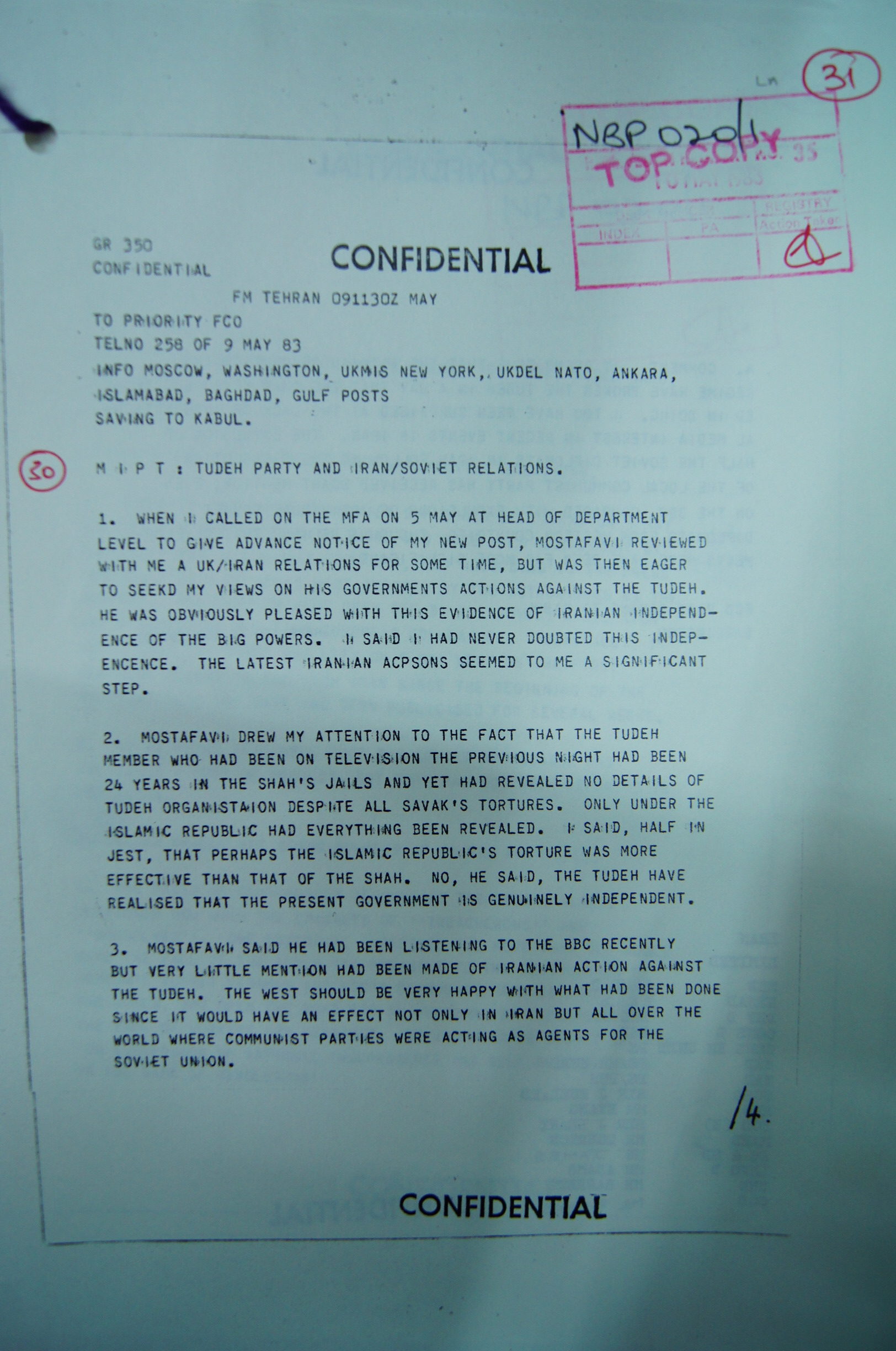

As Iran’s crackdown was under way, Barrington met a senior Iranian official on 5 May 1983 seeking British views “on his government’s action against the Tudeh”, which, he said, was evidence of “Iranian independence of the big powers”.

Barrington replied, according to his memorandum on the meeting: “I said I had never doubted this independence. The latest Iranian [actions] seemed to me a significant step.”

The Iranian official then mentioned to Barrington a “confession” forced by the new regime which had aired the previous night on Iranian television by a Tudeh member who had previously been jailed for 24 years under the Shah. The activist was said by the Iranian official to have previously revealed nothing “despite all the Savak’s tortures” – referring to the former regime’s brutal security service.

Barrington commented: “I said, half in jest, that perhaps the Islamic Republic’s torture was more effective than that of the Shah.”

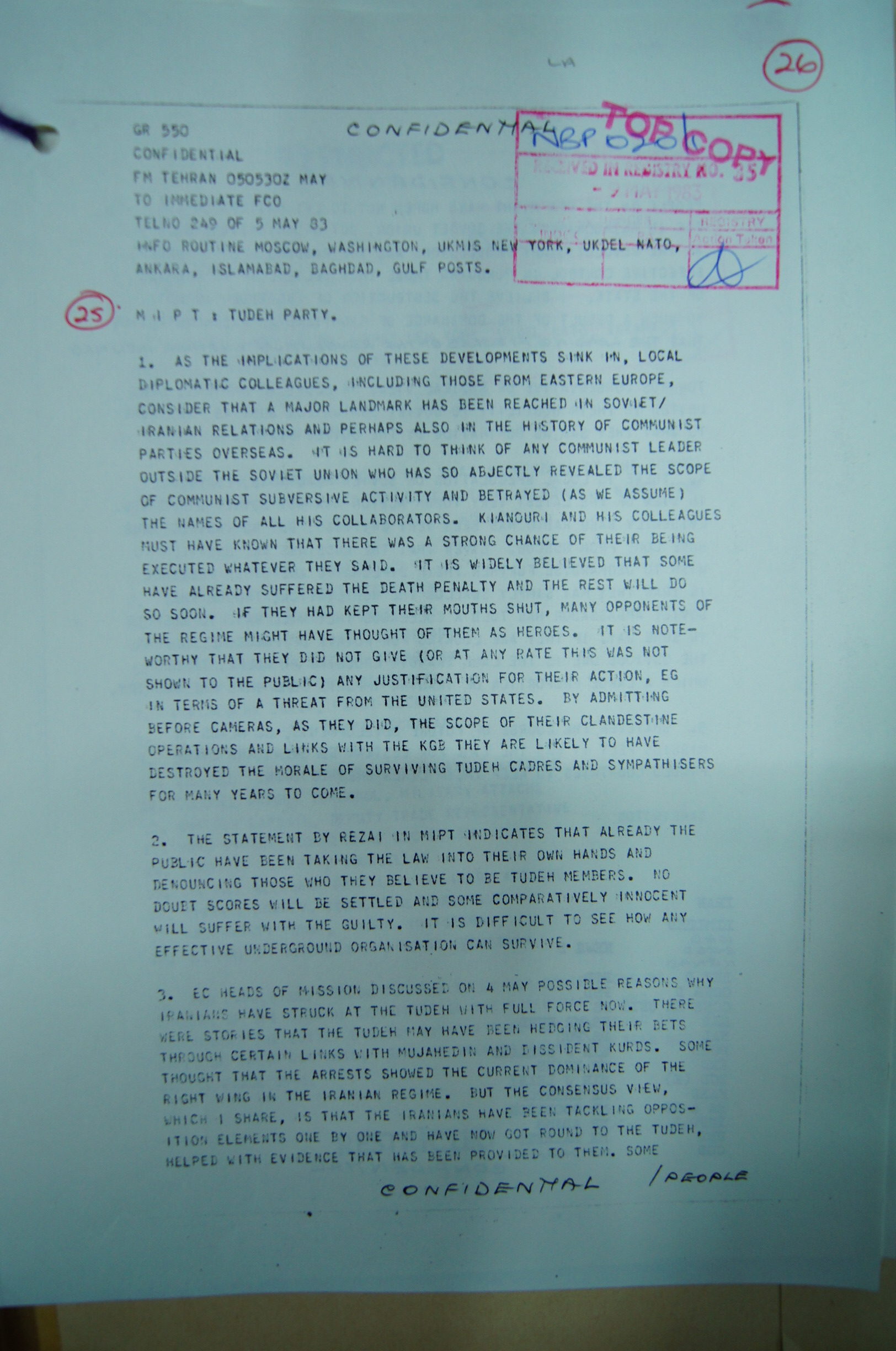

By this time, Barrington and other British officials were well aware of Iranian repression. On the same day he met the Iranian official, Barrington had informed the Foreign Office in London of the “destruction of the Tudeh”.

He noted that “it is widely believed that some [Tudeh members] have already suffered the death penalty and the rest will do so soon”. He added that “the public have been taking the law into their own hands” in dealing with Tudeh members and “no doubt scores will be settled and some comparatively innocent will suffer with the guilty”.

Earlier, in February 1983, when Iran arrested a number of Tudeh members, Barrington commented that “it looks as if the regime are making a determined effort to root out the Tudeh”. By April, Barrington was informed by a Hungarian diplomat that “several hundred” Tudeh members were in prison, who were expected to be dealt with by a military court.

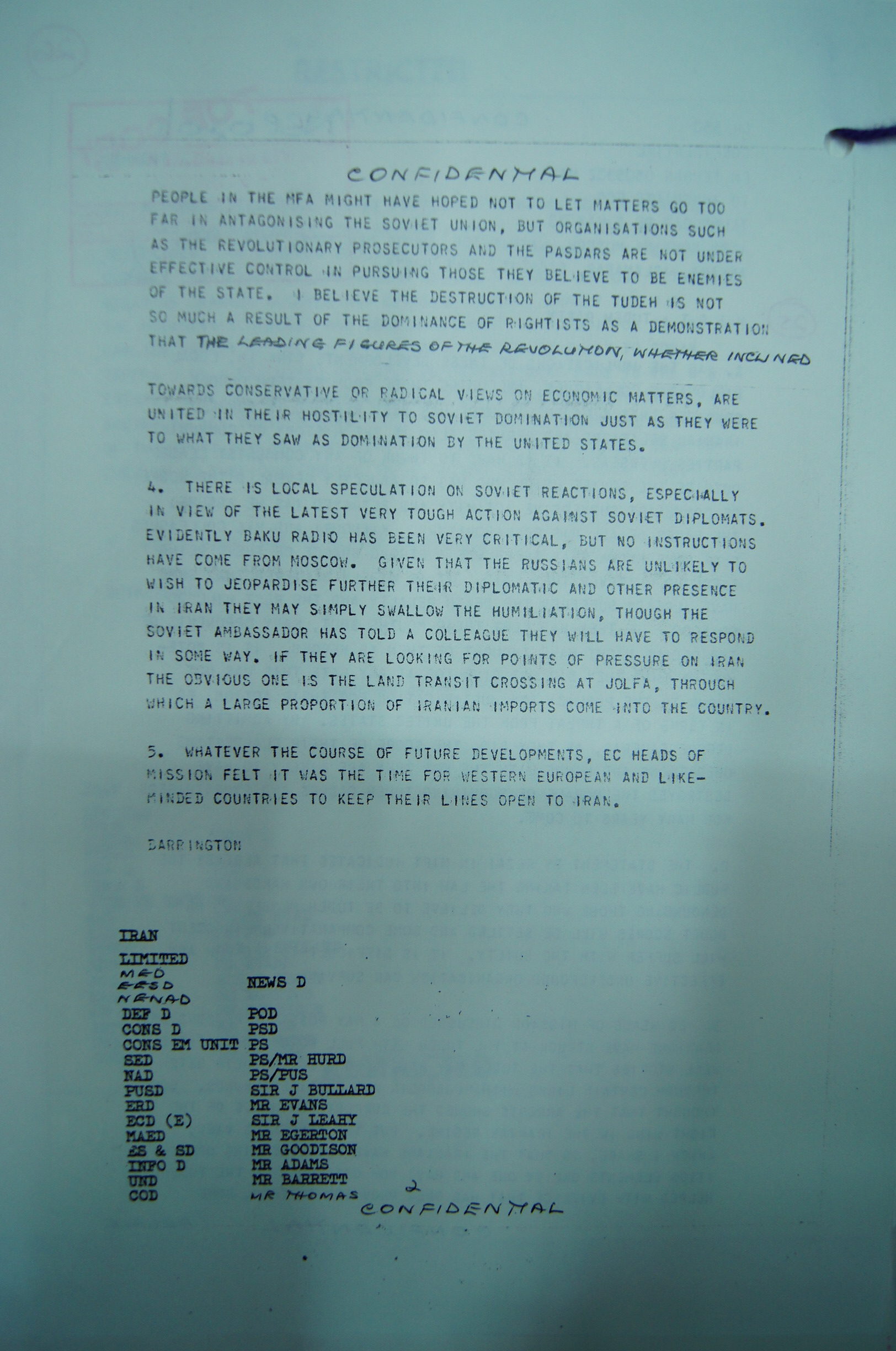

Barrington did not lament the Iranian regime’s actions, but rather saw them as an opportunity. He wrote that fellow European heads of mission “felt that it was time for Western European and like-minded countries to keep their lines open to Iran”.

No evidence could be found in the 1983 files that UK officials did anything other than approve of this severe repression.

Barrington later wrote in his memoir that “there was money to be made” in Iran where “an important part of our work was maintaining British commercial links with Iran and promoting exports”.

By July 1983, another British official in Tehran, Chris Rundle, told the Foreign Office that “some rank-and-file members are being executed and there are rumours of large-scale executions”. He added that the “best estimates here are that about 80% of the Tudeh members in Iran have been arrested, the rest having gone into hiding or escaped”.

Extracted confessions

The Iranian regime’s aim to destroy the Tudeh party was made easier by the forced “confessions” it extracted from two key figures – Noureddin Kianouri, the party’s secretary-general, and Mahmoud Etemadzadeh, editor of the party newspaper.

On 30 April 1983, after nearly two months in jail, Kianouri and Etemadzadeh appeared on television, saying that the Tudeh had worked against Iran and spied for the Soviet Union. Barrington noted that, “The pressures, or threats, in detention must have been great judging by the appearance of the two men.”

A British file from its embassy in Moscow noted a report from Pravda – the official newspaper of the Soviet regime – claiming that the confessions “had been extracted by Gestapo-like methods inherited from the Savak”.

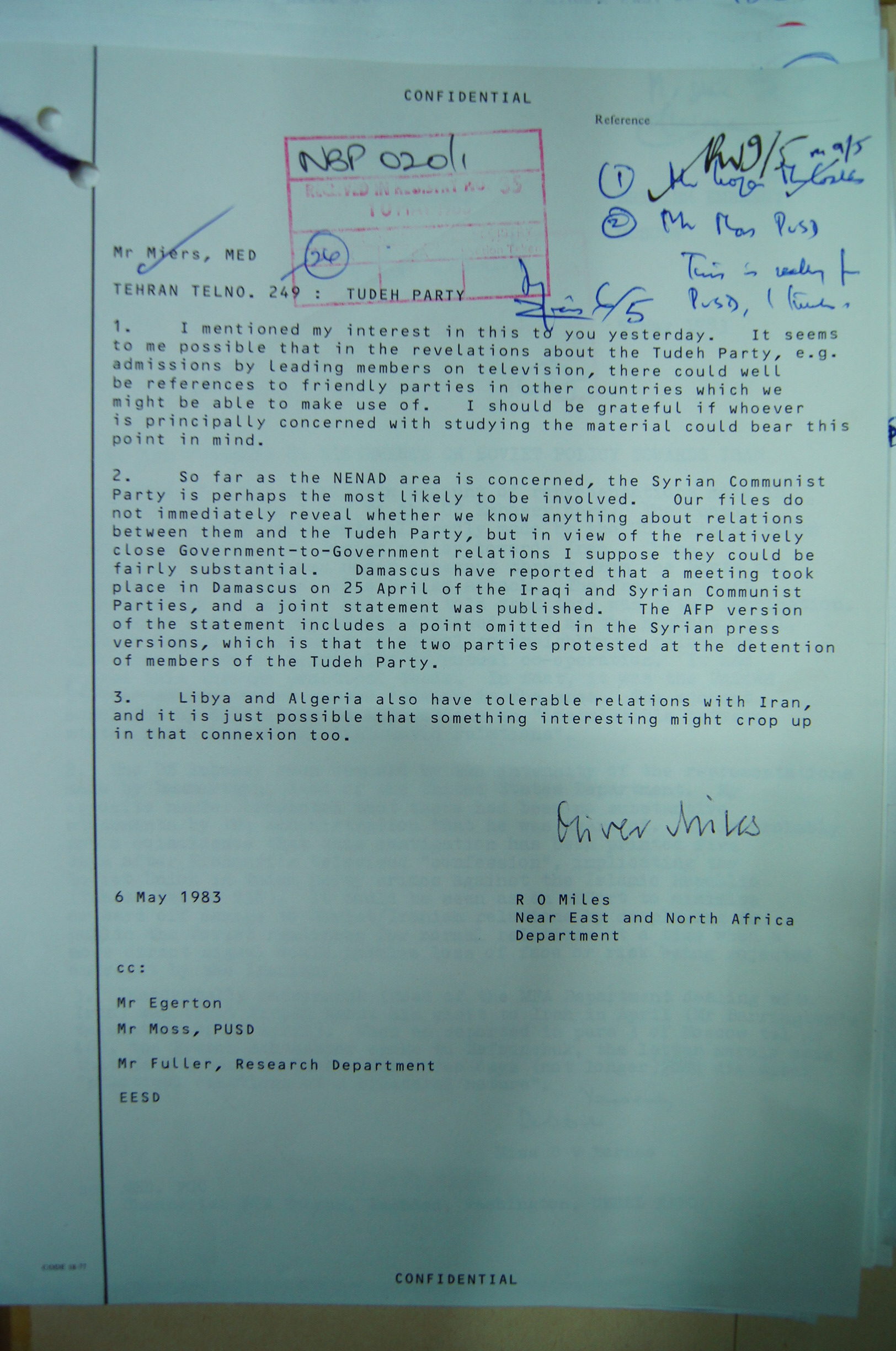

Despite this, the head of the Middle East and North Africa department in the Foreign Office, Oliver Miles, suggested that the “admissions” on television might be useful to Britain. He noted that “there could well be references to friendly parties in other countries which we might be able to make use of”, such as the Tudeh’s relations with the Syrian Communist Party.

Miles also noted: “Libya and Algeria also have tolerable relations with Iran, and it is just possible that something interesting might crop up in that connexion [sic] too”, before adding, “I should be grateful if whoever is principally concerned with studying the material could bear this point in mind”.

Three days later, Barrington reported: “Tudeh cadres are being rounded up in the provinces.”

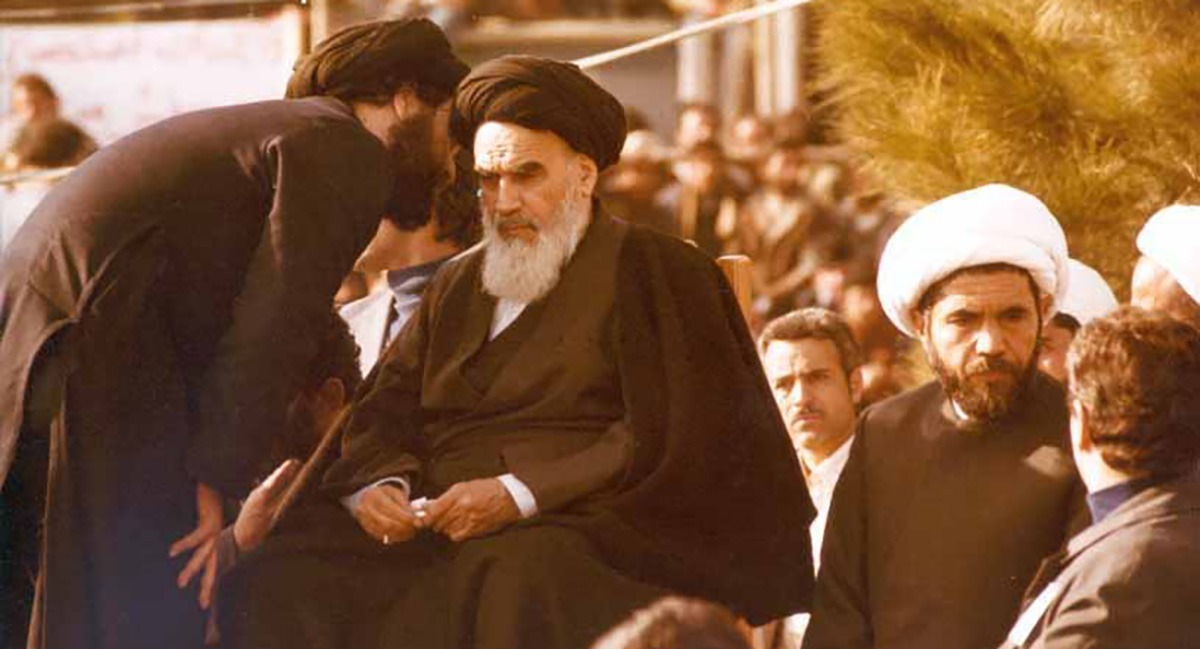

On 4 May 1983, when Iran expelled 18 Soviet diplomats, Barrington noted: “The action against the Tudeh has received the seal of Khomeini’s approval…he praises the revolutionary guards, the other security forces and the judiciary for ridding Iran of the Tudeh, which he referred to as a mottled snake which had been working to overthrow Islam”.

‘A major landmark’

Barrington told the Foreign Office in May 1983 that due to the destruction of the Tudeh “a major landmark has been reached in Soviet/Iranian relations and perhaps also in the history of Communist parties overseas”.

Yet the files suggest that Britain’s support for Iranian repression of the Tudeh cannot be principally explained as a Cold War episode to counter Soviet influence. Officials did not fear the Iranian regime would turn to the Soviet Union since it was implacably opposed to its communism.

There were various sources of friction between Iran and the Soviet Union at this time, notably Moscow’s arming of Iraq, with whom Iran had been at war since 1980. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 had also resulted in millions of Afghans fleeing into Iran.

Neither were the Soviets prepared to go to great lengths to support the Tudeh. Barrington stated in a July 1982 letter to London – by which time Kuzichkin was in the UK passing on information – that while the Islamic regime was in power in Iran, the Russians were “prepared to play it cool and ditch the Tudeh Party, if necessary”.

Barrington went on to receive a knighthood and became Britain’s High Commissioner to Pakistan.

Formal approval for working with the CIA to pass Kuzichkin’s information to the Iranian regime was probably made by then prime minister Margaret Thatcher, foreign secretary Francis Pym and head of MI6, Colin Figures.

An unsuccessful attempt was made to contact Sir Nicholas Barrington for a comment.