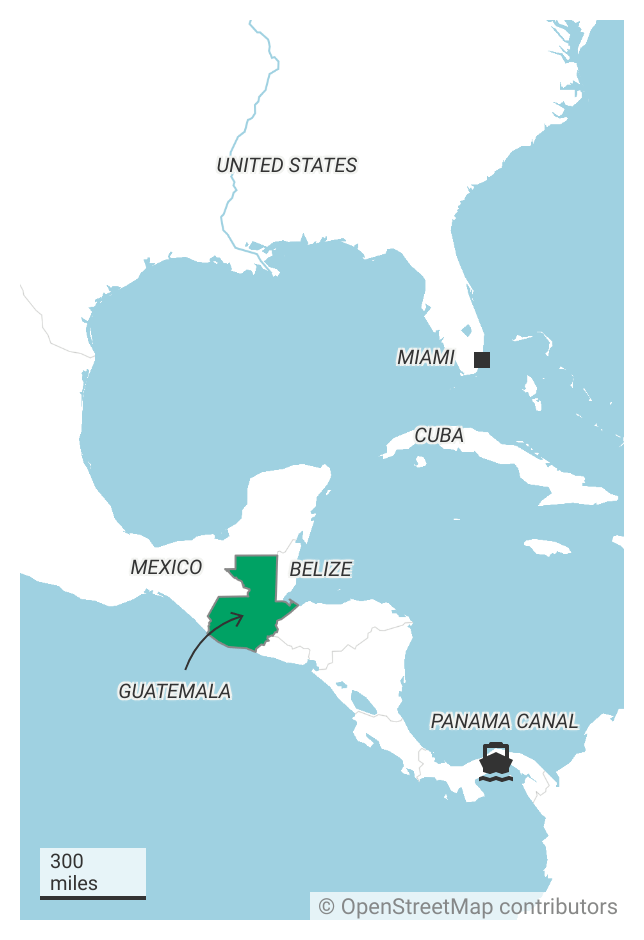

Newly declassified files reveal how the British government played a pivotal role in undermining Guatemala’s democratic government in the early 1950s.

Through the Information Research Department (IRD) of the Foreign Office, British officials inundated the country with exaggerated anti-communist propaganda and funded conspiratorial student organisations.

Ultimately, British intelligence radicalised domestic politics and contributed to the US government’s own efforts to topple Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz using the CIA.

During the 1944-1954 revolution, Guatemalans ousted dictator Jorge Ubico, launched democratic elections, passed moderate labour reforms, and initiated an agrarian reform. Intellectuals, labour activists, journalists, students, and exiles participated in anti-dictatorial movements throughout the Caribbean Basin.

Furthermore, the nation’s people added to the crescendo of anti-colonialist voices across the globe by denouncing British imperialism in British Honduras, then a British colony which would only become self-governing in 1964 and independent as Belize in 1981.

This was partly influenced by Guatemala’s controversial claim to the territory, but the majority of these sentiments targeted European colonialism throughout the world.

Immediately, the Foreign Office conflated Guatemalan nationalism and anti-colonialism with communism. British officials believed communist agents stoked such ideals to build an international bloc and challenge British imperialism at the United Nations.

The Foreign Office frequently suggested Soviet and Mexican officials shaped Guatemalan affairs. These officials even suggested that anti-colonial slogans like “Pan Americanism” and “America for the Americans” were “clearly Soviet-inspired.”

British officials also viewed the Guatemalan people as underdeveloped, incapable, and therefore vulnerable to communist deceptions. One British official alleged that Guatemalan social reforms were communist programmes precisely for this reason, writing, “It seems very dangerous to experiment with combustible doctrines and theories upon the politically uneducated but not unintelligent Indian population of this country.”

“A thorn in our flesh”

By 1950, the Foreign Office believed the combination of democratic reforms and anti-colonial aspirations in Guatemala were nothing more than communist fodder. One official complained, “The ‘democratic bloc’ is a thorn in our flesh as far as anti-colonial agitation is concerned.”

Another believed Guatemala offered “an admirable opportunity for the infiltration of Communist agents, briefed to cause as much trouble as possible to the British in the British Honduras dispute.”

With this view that interpreted Guatemalan developments and anti-colonialism as outgrowths of international and Soviet communism, the Foreign Office ordered its intelligence branch, the IRD, to evaluate the situation.

From 1950 into 1951, IRD officials reached out to myriad Guatemalans in order to better assess the nation’s political trajectory. Among their contacts were notable journalists and newspaper editors.

British officials recognised that many Guatemalan newspapers such as El Espectador and La Hora could not afford subscriptions from international news services. Without the ability to print reports from the Associated Press, these newspapers were desperate for material to fill their pages.

Identifying Guatemalan newspapers’ desire for material, the Foreign Office approved a massive campaign of propaganda inside Guatemala. To hide their agents’ identities, the IRD created fake names including “Rafael Picardo,” “Walter Kolartz,” “Arnold York,” and “Jorge Moncada.”

Under these pseudonyms, British intelligence wrote articles titled “What is a communist?” and “Warning against communist propaganda.”

The articles alleged that Soviet and international communism controlled Guatemala’s government and aimed to take away the people’s political and religious freedoms. In addition, this stream of propaganda included writings produced by IRD agents in the rest of Latin America and the world.

Flood of anti-communist material

Into 1954, the IRD inundated Guatemalans with a flood of anti-communist material by publishing as many as three dozen articles in a month. British officials admitted that “most of the papers normally reserve an encouragingly large amount of space for our material, which is being distributed most efficiently from the Legation.”

The IRD stressed that the “smaller papers also publish well our shorter items from all parts of the world.” Because of the IRD’s efforts, British officials’ propaganda could be found throughout the nation, contributing to an increasingly tense political environment.

Additionally, the IRD supported the anti-government student organisation Comité de Estudiantes Universitarios Anti-Comunistas (Committee of Anti-Communist University Students, CEUA). The CEUA was composed of conservative students who opposed Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz.

After gaining support following protests against the replacement of nuns in the nation’s largest orphanage, IRD officials identified the CEUA as “further proof of the anti-Communist feelings of the Guatemalan people” and made contact with the organisation’s leaders.

The CEUA gladly responded and offered the IRD documents outlining the organisation’s goals and structure. They depicted themselves as opponents of communists under the “Iron Curtain” who sought to strip Guatemalans of their individual rights and Christian religion.

The CEUA argued that it would take any and all action as would “liquidate Communism wherever it raises its head.” To prove its strength, it emphasised its relationships with anti-communist political parties, Catholic leaders, military officers, and market women throughout the nation.

The IRD agreed that the CEUA was a useful vehicle for disseminating anti-communist propaganda throughout Guatemala. In fact, CEUA officials already volunteered “to distribute such material” that British officials could provide.

On top of the IRD’s work through the nation’s various newspapers, this student organisation would further expand the reach of British policy by “distributing anti-Communist propaganda in the towns and villages” of the country. IRD officials encouraged the Foreign Office to approve this funding.

Over the next years, the CEUA would continue distributing anti-communist propaganda. Its signs, banners, pamphlets, and stickers repeatedly claimed that Soviet and international communism dominated the nation.

Its slogans and phrases, “The Soviet Paradise,” “The Hydra of Communism,” “No More Hurrahs for Russia or Stalin,” “Out with Communism,” and “Guatemala for Guatemalans,” spread.

CIA and IRD division of labour

Although British officials played an important role in radicalising Guatemalan politics through such propaganda, the Foreign Office appears to have refused to directly fund any anti-government conspiracies or uprisings that might reveal the British hand.

When Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas sought support from the British in 1951, the Foreign Office denied this solicitation. When Caribbean Basin dictators tried organising a border invasion in 1952 and asked permission to use Belize/British Honduras, the Foreign Office put down the suggestion.

In fact, British officials even suggested that the US government had “the main responsibility and the chief means of combating Communism in Guatemala.” As US officials in 1952 were approving the CIA to begin working with Castillo Armas and the dictators under Operation PBFORTUNE, the British government kept its efforts focused on the IRD’s propaganda campaigns.

Because British officials walked this line, their hand in interfering in Guatemala’s domestic affairs remained hidden until now. From 1953 into 1954, the US through the CIA launched Operation PBSUCCESS which unified the anti-government opposition.

Alongside a campaign of psychological and economic warfare, the CIA backed a border invasion and encouraged the Guatemalan military to overthrow Arbenz’s government.

Following this notorious coup, successive governments and military regimes beginning with that under Castillo Armas engaged in numerous atrocities whose legacy continues to shape the nation as scholars and experts understandably sought to uncover the US government’s role.

The British government, though, did radicalise Guatemalan politics through the IRD’s covert propaganda campaigns. Its agents’ hyperbolic articles appeared in multiple newspapers on a regular basis, with some even reprinted and distributed by US officials in the early 1950s.

“The ‘democratic bloc’ is a thorn in our flesh as far as anti-colonial agitation is concerned.”

The CEUA was a key entity in Operation PBSUCCESS due to its members’ willingness to spread anti-communist propaganda. Some CEUA leaders who worked with British intelligence simultaneously worked with the CIA and received central posts in Castillo Armas’s regime.

When the US government put Castillo Armas into power, the British Minister in Guatemala City Richard Allen admitted “one or two men now appointed by [Castillo Armas] to influential posts are precisely those who did us good service and ran considerable risks as our contacts for the distribution of anti-Communist IRD material.”

After the coup, British public opinion and Labour officials demanded that the United Nations launch a thorough investigation of what transpired in Guatemala. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles warned British officials from pursuing the investigation by warning that the US government would be more critical “if and when such matters as Egypt, Cyprus, North Africa or the Middle East come up before the United Nations.”

In the end, the Foreign Office halted any inquiries and insisted that Guatemalan affairs fell under the jurisdiction of the Organisation of American States, placating US officials.

Whereas Dulles’s actions signalled the role of the US government in destroying Guatemalan democracy, sources now prove that British officials had actually pursued their own form of intervention against the Guatemalan revolution.

Aaron Coy Moulton is Assistant Professor of Latin American History at Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas. He is the author of multiple articles on Caribbean Basin dictatorships, espionage, and more.