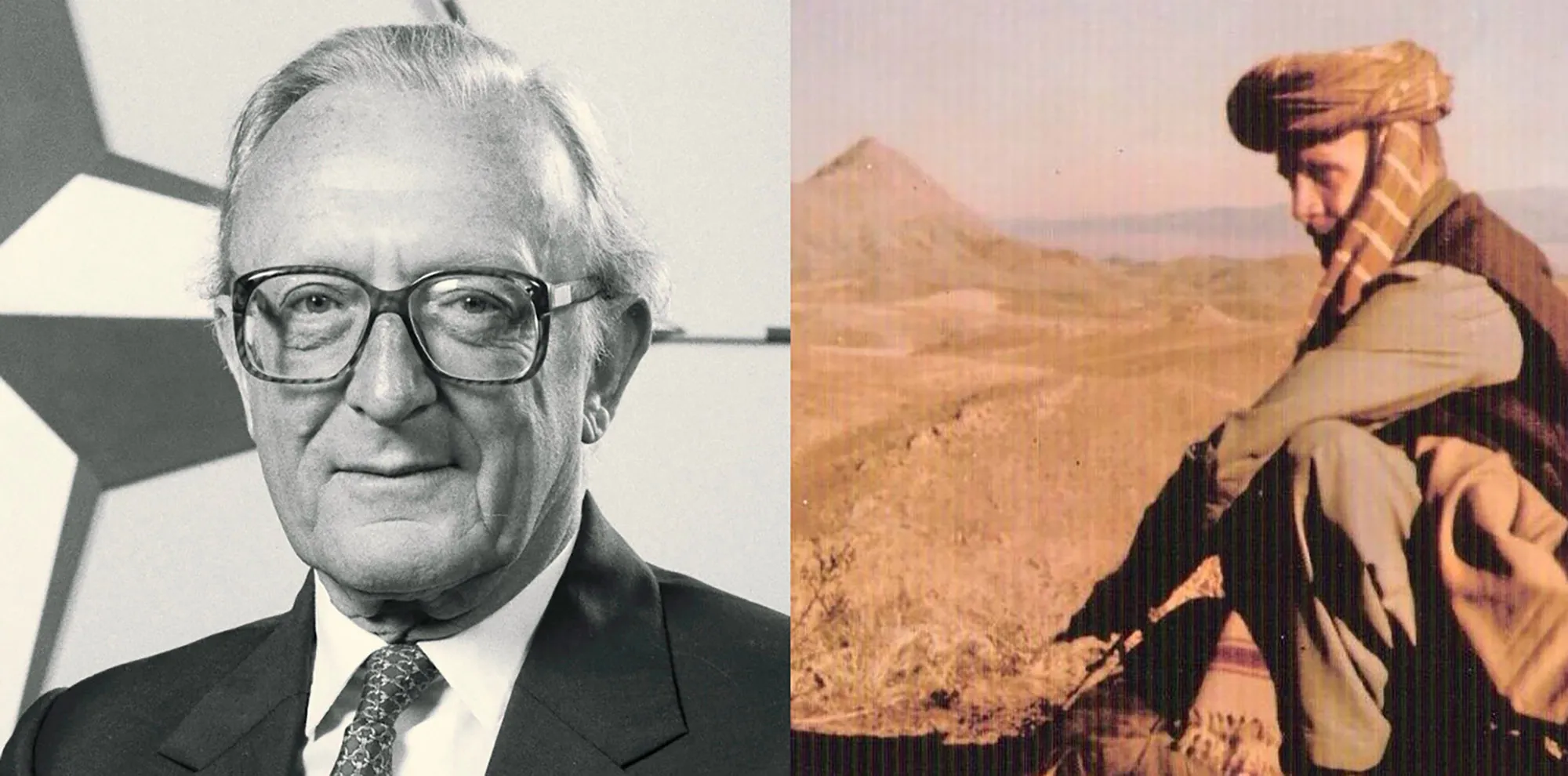

In 1980, journalist John Fullerton sat down for lunch in London with members of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), better known as MI6. The spooks asked the restless reporter to name five cities where he would like to work. He scrawled the answers unhesitatingly on a paper napkin.

“The top one was Peshawar in Pakistan,” he told Declassified, explaining his desire to move near the turbulent Afghan border. “The Soviets had invaded Afghanistan but I couldn’t find ways to be a freelancer out there. There were no journalists covering it. Everyone had left Kabul. So I wanted to cover the war and that’s how SIS employed me.”

He had been on good terms with SIS for many years already, after a chance encounter with Nicholas Elliott, one of the agency’s high fliers. Elliott, who famously confronted the KGB double agent Kim Philby, had just retired as an SIS director when he spotted an article by Fullerton exposing a power struggle between the police and military in apartheid South Africa.

Fullerton grew up in Cape Town, rising to night news editor on the Cape Times before migrating back to the UK, the country of his birth. After checking he was not a mole for the apartheid regime’s Bureau of State Security, British intelligence eventually took him on as a “contract labourer”, a cheaper option than a permanent SIS officer position.

“They employed quite a lot of these contract labourers, many from military backgrounds,” Fullerton commented. “SIS had gone through a period of retrenchment in the 1970s and early 80s and it had shrunk. From having three fully staffed stations in Latin America it went to having none.”

This all changed under Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who received informal advice on espionage from Elliott. “She took a great interest in foreign affairs and intelligence and she tried to beef it all up,” Fullerton remarked, adding that her Foreign Secretary Lord Carrington was eager to get “scenes of Afghans fighting communists onto television screens.”

Carrington told his department in a classified memo from 1980: “The Afghan insurgents should be brought to understand the value of publicity, which means that films of Soviet military activity (for example, their attacks on villages, and the destruction of houses and crops) should be readily available. It should not be difficult to encourage the supply of film, cameras, etc, to the insurgents, who should be encouraged to record Soviet excesses.”

So when Fullerton wrote Peshawar on his napkin months later, Whitehall was more than ready to support his career move. They dispatched the 31-year-old to Fort Monckton, an SIS training school in Gosport, southern England, where he learnt tradecraft: how to compile intelligence reports, interview assets, follow a target or lose a tail.

Most important was a crash course in operating the Super 8 video cameras that he would supply to Afghan exiles.

The Foreign Office took a similar approach to Syria’s civil war thirty years later: funding scores of citizen journalists to supply Western media networks with a steady stream of regime atrocities and stories of rebel victories.

In the 1980s, Britain’s psychological operations for Afghanistan were more experimental, with Fullerton having to find suitable cameramen among the maze of mujahideen groups in Peshawar or sometimes crossing the border with them to reinforce his journalistic cover as a freelance foreign correspondent.

Fullerton’s espionage along the Afghan/Pakistan frontier forms the basis for his gripping new novel Spy Game, which, although fictional, closely follows his own experience and chimes with declassified Foreign Office files at the National Archives.

His insider’s perspective is especially valuable since SIS has never published its records from its actions against the Soviets in Afghanistan. These ran parallel to Operation Cyclone, one of the CIA’s longest and most costly covert operations, unleashed by President Carter in 1979 and continued under Ronald Reagan.

‘Right-wing religious fanatics’

Fullerton worked for SIS as its head agent in Peshawar from 1981-83, before joining Reuters news agency and drifting away from the intelligence community. Although his initial assignment in Afghanistan was limited to information gathering, agent running and obtaining footage, Lord Carrington had far more hawkish aspirations.

The Foreign Secretary, who oversaw SIS, wanted the Afghan mujahideen to receive “the sort of man-portable missiles that infantry use against low-flying aircraft” as well as “anti-tank mines”.

Surface-to-air missiles and landmines in Afghanistan would later cause the West massive concern, but Carrington had no such hesitations in the early 1980s.

He noted: “It seems to me that this, though a tricky area, is one where the Afghan liberation movement deserves a measure of support, and one where the injection of some slight assistance may pay substantial dividends.”

Despite Carrington’s early zeal, Fullerton believes SIS only became more proactive towards the mid-80s. “In my time they were quite tentative,” he said. “They were happy just to try and get some propaganda going, trying to get people to help the mujahideen, and that was enough as far as the British were concerned. It was only later they started to try to push for help for Ahmad Shah Massoud.”

Massoud, known as the ‘Lion of Panjshir’, occupied a strategic valley near Kabul which was a stronghold of resistance to the Soviets. Long portrayed as a moderate force in Afghanistan, his son, also named Ahmad, is currently among the few remaining warlords holding out against the Taliban.

The increased focus on Massoud may have come about in 1983 when the CIA’s Afghan Task Force chief, Gustav Avrakotos, met with SIS in London and realised the British agency was “virtually bankrupt”.

Despite lacking funds, Avrakotos believed SIS had fewer legal constraints on its activity than the CIA and better understood Afghanistan’s terrain from its imperial expeditions in the country, especially the military significance of the Panjshir Valley.

Massoud’s militant group, Jamiati Islami (Islamic Society), was Fullerton’s “favourite organisation” to work with in Peshawar, but its men had some dangerous tendencies. “There was this great poster on the wall of Jamiati Islami and it had a grave,” he recalled.

“Next to the grave were two coffins. One with a US flag wrapped around it, and the other with a Soviet flag. And it was death to both. So on the one hand they would accept guns from the West but on the other hand they would resent those people who were trying to enforce their view of the world on them.”

Fullerton fed back to the British embassy in Islamabad information on the different currents within the Afghan opposition. Declassified files show the Foreign Office regarded Massoud’s group as “right-wing religious fanatics” even before Fullerton arrived in Peshawar.

‘Kick out the Red Colonialism’

There were few exiles in Peshawar who Fullerton trusted. “I met Afghans who were secular nationalists and I’d get along with them far better than with anyone else but they represented nothing very much. They were tiny factions. It was pretty hopeless, I thought anyway. They didn’t have much power on the ground.”

Left-wing Afghans who became disenchanted with the Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Party government in Kabul also came across Fullerton’s radar in Peshawar, but they lived in fear of reprisals from Pashtun religious groups and their principal backers, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

“I think the Americans were supplying the wrong people because the intelligence they were getting was flawed,” Fullerton reflected. “They’d subcontracted the intelligence to Pakistan’s ISI. Pakistan had a forward policy which was to control Pashtun areas of Afghanistan, to ensure that whoever was in Kabul was their man and basically to create a huge cordon sanitaire.”

Pakistan was afraid of being encircled by its old rival India and wanted a buffer zone on its northwestern flank in Afghanistan.

“The ISI was interested in giving all this largesse or some of it to their people and their people were basically Islamist”, Fullerton added.

The Foreign Office files support his assessment, with one official noting: “The Pakistani government, including President Zia, favour the more fundamentalist, and generally more active, resistance groups. This makes sense in that President Zia is himself something of a fundamentalist.”

As a result of this political dynamic, the largest recipient of CIA funds from Operation Cyclone was Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the leader of the “very hardline” Hezbi Islami (Islamic Party) and someone who Fullerton regarded as “a nasty character”.

By the time Fullerton came across this group in Peshawar, Hekmatyar had already written to Thatcher praising her “humanistic feeling” and calling for her support. “Hezbi Islami Afghanistan is prepared to accept any aid without conditions from any friendly nation to kick out the Red Colonialism from Afghanistan”, the group told the prime minister.

Hekmatyar went on to visit London in 1986 and 1988.

When the Soviets were eventually evicted from Afghanistan in 1989, Hekmatyar battled for supremacy among rival warlords, during which his forces were accused of heavily shelling civilian areas of Kabul and raping women.

Hekmatyar triumphed and briefly became Afghanistan’s prime minister before fleeing when the Taliban took over in 1996. After 9/11 he switched sides, declaring his support for the Taliban and Al Qaeda and spending the next 15 years directing attacks on Nato forces in Afghanistan.

The CIA’s former client was designated as a terrorist and targeted (unsuccessfully) in a US drone strike.

Another spectacular case of blowback from Operation Cyclone involved the Arab mujahideen who came to Afghanistan and Pakistan in the 1980s to help fight communism.

“I would go to an Afghan commander’s house in Peshawar and I’d see figures darting around inside going in doorways and up staircases,” Fullerton recalled. “I’d learn later that those were Arab volunteers. Then I saw on the corner of the street where I lived in University Town a group of Arabs in white robes and headdresses — it might have been Osama Bin Laden, who knows. He did live in University Town.”

“The Afghans treated them with contempt,” he added. “They had to put up with them because they were accepting Saudi money and weapons, so they said we’ll have to take these people, but they thought they were pretty useless at fighting.”

Rallying the Arab world against the Soviets brought money to the Afghan mujahideen but carried huge risks for the West. “The Americans were paying for the making of all those tapes and recordings inciting people to rise up against Communism. If you start poking your fingers into all that and start encouraging a resurgence of a militant Islam on the world stage it’s going to burn your fingers eventually, it has to,” Fullerton reflected.

“In Egypt they were distributing all these tapes and recordings of various leaders imploring their followers to go and fight in Afghanistan and resist the Soviet evil. Well, where does that end? There was short-termism. We needed to look at the long term effects this was going to have.”

As early as April 1980, the Foreign Office in London had concluded in a secret memo that “from the point of view of the West there is no evident individual [Afghan opposition] party that merits support over the others.” It cautioned that “the fundamentalist groups are unlikely to be any more sympathetic to the West than they are to the Soviet Union.”

Yet Whitehall spurned opportunities to align with less violent currents of Islamic tradition such as Sufism. In May 1980 a British diplomat met with a Quranic institute in Lahore which disseminated “Sufic literature to the mujahideen in Afghanistan” in an attempt to overcome tribal and political rivalries among the rebels.

The US embassy in Pakistan appeared uninterested in their efforts and the British diplomat commented that “Sufism seems to be a pretty esoteric branch of Islam, and it is hard to see its propaganda having much success amongst the rebel fighters. I see no advantage in us becoming more closely involved.”

‘Hunky muscled types’

Western spies were not the only ones supporting the mujahideen. “There were all these hunky muscled types wandering around Peshawar with cameras round their necks,” Fullerton commented, recalling the arrival of foreign mercenaries in Pakistan. “They looked absurd and when they saw me on the road in my tatty tweed jacket they all sort of ran away.

“British mercenaries were hired by the Pentagon when I was there,” Fullerton expanded. “They were hired under the name Ice Cargo, I think, which was signed into a hotel in Peshawar. They were led by an Englishman in a suit on the ground in the hotel.”

In at least one case, their ranks included an SIS officer who had served in the Royal Marines.

“Their job was to go over the border and try to get the bits and pieces of the Soviet Hind helicopter gunship and other bits of kit for the Pentagon,” Fullerton explained. “They were trying to muscle in on the CIA’s territory, it was an intra-bureaucratic wrangle.”

Although these initiatives helped the mujahideen roam the Afghan countryside, Fullerton felt the Soviets did not seek total control of the country. “They realised that the countryside was the countryside and you can’t control it. There’s no point in seizing a hill or a valley because you’re going to have to leave sooner or later.”

Instead, the Red Army “limited their operations to keeping a ring road open between the major cities. The Soviets only really very late on mastered the technique of coming out into the countryside with special forces and setting up ambushes, or forming counter-gangs dressed as mujahideen and making contact with mujahideen groups and then wiping them out.”

As Soviet military tactics evolved, so did the mercenary ambitions. Toward the end of Fullerton’s time in Afghanistan, during 1983, a British man using the alias Stuart Bodman was killed in a Soviet ambush.

He was reportedly working for KMS Ltd, a London-based mercenary firm that was hired by US intelligence to plant a network of miniature eavesdropping stations in Afghanistan to detect Soviet troop movements.

KMS is said to have held another Afghan-related contract, awarded by President Zia to train Pakistan’s special forces, whose troops included a proportion of mujahideen. The scheme initially ran into difficulty when KMS took the troops over the Afghan border to test their skills, and they encountered elite Soviet Spetsnaz fighters who inflicted heavy casualties.

KMS director David Walker is believed to have contacted US intelligence about enhancing his training camp in Pakistan, complaining that “the system does not allow instructors to get close to their Afghani students, to get a good feel for the operational conditions and requirements, and to build that close relationship which is so important.”

As a result, Walker sought £160,000 a year from the CIA to supply three or four KMS instructors who would train mujahideen in Afghanistan. “The instructors will have a broad base of experience in unconventional warfare skills, but will expect to teach two main skills to start with: a) demolitions and sabotage, b) paramedical aid,” Walker wrote.

Meanwhile, a former British army captain, Anthony Knowles, approached the US embassy in London in May 1985 with a similar proposal for KMS to train Afghan mujahideen in demolition techniques inside Afghanistan.

Knowles was jailed in 2016 for tax fraud. The Metropolitan police is currently investigating allegations KMS committed war crimes in Sri Lanka, where it supported the country’s military fighting a brutal civil war.

‘As clandestinely as possible’

The extent of Whitehall’s support for Cold War mercenary operations in Afghanistan is hard to ascertain. By October 1980, the prevailing view in the Foreign Office was that “any military assistance for the Afghan rebels should be provided as clandestinely as possible”, which frustrated right-wing MPs who wanted to proceed overtly.

Winston Churchill MP, grandson of the wartime leader, told Carrington in a letter: “Assuming that the Western nations do not wish to see the Third World over-run by the Soviet Union and their surrogates… we must owe it to those who are resisting the Soviet yoke… to provide them with the means to carry on that resistance”.

He added: “In addition to Army surplus and outdated equipment it would seem that there is one specific item of new equipment of which they have a desperate need, namely infantry-portable surface-to-air missile. I would have thought that the Blowpipe manufactured in this country would be ideal.”

He continued: “Even if we were only able to make available 100 missiles together with a small specialised training team … of course if Her Majesty’s Government does not wish to be seen to be directly involved, I have no doubt that suitable intermediaries could be found such as Oman or one of the Gulf States.”

SAS veteran Ken Connor claimed in his book Ghost Force that such covert support saw members of Massoud’s faction taken out of the Panjshir valley one winter by two British special forces veterans and trained in the Middle East.

The group also visited rural locations in the UK to receive live firing sessions with instruction on operational planning, aggressive tactics, use of explosives, mortars and artillery. The mujahideen were even said to be taken on helicopter flights to appreciate the difficulties for pilots of finding human targets, to overcome their fear of Soviet gunships.

These courses included further coaching on clandestine entry into airbases, mining runways, luring ground-attack aircraft into narrow valleys where they could be destroyed by crossfire, and ambushing columns of armoured vehicles.

Connor claims the CIA also sought advice from MI6 and the SAS on such tactics, and within a month of a British plan being drawn up, the mujahideen had managed to destroy nearly two dozen Soviet Mig fighter jets on the ground in Afghanistan.

Other sources close to the intelligence community, such as BBC reporter Mark Urban, have reported the CIA and SIS sent 300 Blowpipe surface-to-air missiles from a factory in Belfast to Afghanistan between 1985-86.

‘The height of criminality’

Ultimately these efforts culminated in the defeat of the Soviet occupation, but building a durable peace has proved far harder. Speaking by phone from his home in Scotland in May, Fullerton told Declassified he had “very mixed feelings” about the then looming US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

“The Americans have lost a war and they’re trying to use cosmetics to make it look better than it is. On the other hand, I don’t think it was ever winnable the way they were doing it, because the government in Kabul does not have any real hold on the Afghan people or on the territory. It probably never has had,” he said presciently.

“I don’t think the Americans have ever been able to square the circle of relying on so-called warlords or local leaders and trying to get the bulk of the population into some semblance of order and peace. I don’t have answers. I just don’t think a foreign power can use military force to obtain the results it wants in Afghanistan.

“And I don’t see why the British would want to get involved,” he added. “What’s the strategic interest? How is the national interest in the UK served by getting involved in places like that? I don’t think the UK knows what its national interest is.

“We seem to know what the American national interest is, and that we should follow their lead. But what is actually in the interest of the UK population is another thing, in terms of social housing, land reform and all that. It doesn’t lie in sending a carrier strike force into the Taiwan Strait,” he commented, lambasting the Royal Navy’s decision to send one of its new aircraft carriers to patrol the South China Sea.

Fullerton, who now supports Scottish independence, says the invasion of Iraq “was the final break with the British state as far as I was concerned. Watching it unfold from Reuters in London I couldn’t believe they were going to do this.

“I didn’t believe we had a Prime Minister who would lie openly, consciously, to Parliament and then fix the intelligence to fit the policy in such a blatant way and go into a war which was obviously going to destroy so many lives — it was clearly going to do that.

“It seemed to me the height of criminality basically. It just boggled the mind at the time. And like a lot of people we went out on the [anti-war] march but, of course, the march was pointless. They didn’t take the slightest bit of notice of the three million people on the streets. Why should they? I’d started to get disillusioned long before that but I think Iraq was the final proverbial straw.”

Fullerton’s new novel, Spy Game, is available from Burning Chair for £8.99.