Boris Johnson was shunted out of office by cabinet colleagues increasingly worried about their own careers and electoral prospects. But the prime minister’s downfall was encouraged, even engineered, by parts of the Whitehall establishment.

This included Britain’s top spooks – what I call the ‘permanent government’ and in the US they call the ‘deep state’. It was a personal victory for a long list of unelected officials.

Among them were both of the prime minister’s old ethics advisers, namely Lord Christopher Geidt – an ex-army intelligence officer who had worked for the Queen – and Sir Alex Allan, a former chair of the Joint Intelligence Committee; as well as Sir Philip Rutnam, former permanent secretary at the Home Office; Lord Jonathan Evans, the former head of MI5 who now chairs the Committee on Standards in Public Life; and Lord Simon McDonald, former permanent secretary at the Foreign Office.

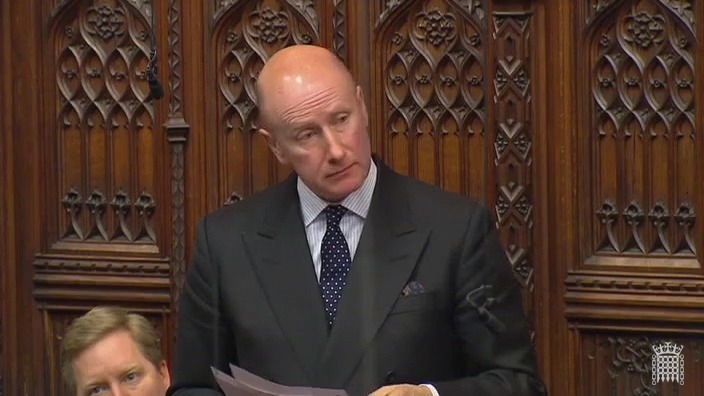

It was McDonald’s decision to publish a letter accusing 10 Downing Street of telling lies over what Johnson knew about the behaviour of his former deputy chief whip that was the last straw for hesitant ministers.

After Johnson announced his resignation last Thursday, McDonald tweeted triumphantly: “It was a good day.”

But McDonald’s move was just the latest in a series of interventions by establishment figures that helped cut short the prime minister’s mandate, after Johnson won an 80-seat majority in December 2019 to run the country for the next five years.

Within months of that landslide victory, Sir Philip resigned in protest against alleged bullying by his boss, home secretary Priti Patel. He sued the government for constructive dismissal, and settled out of court for a reported six figure sum.

Sir Alex then stood down after Johnson rejected his advice that Patel had not “consistently met the high standards required by the Ministerial Code of treating her civil servants with consideration and respect”.

More recently, Lord Geidt resigned after he said Johnson had put him in an “odious and impossible position” by asking him to “risk a deliberate and purposeful breach of the ministerial code”.

Lord Evans has not resigned, but used his committee’s platform to call for stricter guidelines covering leadership and ethical behaviour. “The political system in this country does not belong to one party or even to one government…It is a common good that we have all inherited from our forebears and that we all have a responsibility to preserve and to improve”, he said.

Brexit and beyond

Britain’s top spooks in MI5, MI6, and GCHQ – and senior counter terrorism officers in Scotland Yard – were opposed to Brexit. After the 2016 referendum, they strongly opposed the hard Brexit Johnson demanded, as it broke off close institutional cooperation with their European counterparts, threatening speedy information-sharing on counter-terrorism and other criminal investigations.

Claims that Johnson was leaving secret intelligence reports lying around for all to see in his Downing Street flat reflected increasingly widespread concern in MI5 and MI6 about his behaviour.

Sir Richard Dearlove, head of MI6 when the agency was responsible for misleading dossiers on Saddam Hussein’s weapons programme before the invasion of Iraq, was the only “securocrat” in favour of Brexit. His grounds were that it would give Britain control over immigration. Curiously, Dearlove also objected to the European Court of Human Rights, which is not an EU body.

Concern about Brexit among Whitehall’s mandarins has been compounded by what they regard as Britain’s declining reputation and standing in the world – and Johnson’s clownish boosterism.

Sir Ivan Rogers, Britain’s EU representative in Brussels, had earlier quit his post over the government’s handling of the Brexit negotiations.

Senior civil servants were aghast when the government decided unilaterally to change the Northern Ireland protocol it had agreed as part of the Brexit negotiations. Sir Jonathan Jones, the government’s top legal adviser, resigned over the decision.

Yet opposition to Johnson and his close political clique was (and remains) much broader than Brexit. What the civil service hierarchy in Whitehall say it is concerned about is propriety, sticking to the rules, opposing corruption in all its manifestations, the waste of taxpayers’ money (though the Ministry of Defence is a notable exception), and “jobs for the boys”.

The growing chumocracy has led to mounting frustration, anger, and even panic in Whitehall. Let us recall the handing out of lucrative Covid-related contracts to Tory friends and donors; ministers discussing official business with their political advisers on private emails away from the prying eyes of civil servants; Priti Patel’s failure to be candid about unofficial meetings with prominent Israeli politicians (leading to Theresa May’s decision to sack her); Johnson’s meeting when he was foreign secretary with ex-KGB officer Alexander Lebedev in his Italian palazzo without officials, and his subsequent awarding of a peerage to Lebedev’s son.

Aided and abetted by his more cavalier ministers and coteries of political advisers, Johnson also bypassed the Public Appointments Commission, part of whose role is to ensure that those involved in such appointments act with “integrity” and “merit”, declaring any relevant interests and relationships.

Downfall

Johnson’s praise of the Civil Service as “peerless” and of the “agencies” – a reference to MI5, MI6, and GCHQ – as “so admired around the world” in his resignation speech outside 10 Downing Street was pure humbug.

Simmering and growing concern throughout Whitehall about Johnson’s lying and the moral corruption in Johnson’s bunker erupted into the open last week when Lord McDonald revealed he had written a letter to Kathryn Stone, the parliamentary commissioner for standards, saying that despite repeated claims, Johnson had known about previous allegations relating to Chris Pincher, the deputy chief whip suspended for allegedly groping two men.

Referring to 10 Downing Street claims that “No official complaints against [Mr Pincher] were ever made”, McDonald told Stone: “This is not true”. In a subsequent interview with the BBC, McDonald said: “I think they need to come clean”. He described a “sort of telling the truth and crossing your fingers at the same time and hoping that people are not too forensic in their subsequent questioning and I think that is not working.”

The letter, and McDonald’s decision to publicise it, reflected Whitehall’s determination to fight its corner in any way it could.

McDonald was keen to attack Downing Street, but he might also have looked at his own backyard. His Foreign Office showed complete disregard for countless civilians killed in Yemen by UK-supplied weapons. And he personally instructed Britain’s ambassador to Burma to be “more flexible” with Aung San Suu Kyi’s regime, as her military committed a genocide of Rohingya Muslims. His old department has also indulged in obsessive secrecy and has refused to declassify files from decades gone by.

Julian Smith, an MP and former Northern Ireland Secretary who was sacked by Johnson, enthusiastically championed the Whitehall establishment, saying civil servants were “up in arms” and tweeting that they had “literally held the administration together”.

The former Head of the Civil Service, the crossbench peer, Bob Kerslake, who had previously criticised the government for withholding official documents from the National Archives, told the BBC at the height of the Pincher row: “There must be a complete openness and transparency from No 10 and the Prime Minister”. The former and long-serving Cabinet Secretary, Lord Butler, has repeatedly implored civil servants to talk truth to power, meaning to their political bosses, not to the public.

And there’s the rub. It is a bit rich for Whitehall, the “permanent government”, to call for more openness and transparency when it has thrived on official secrecy and keeping information from the public to avoid embarrassment, suppress wrongdoing, and protect itself from independent scrutiny. Without warnings by websites and outlets beyond the mainstream media such as Declassified, Whitehall will continue to do so at a time civil liberties and freedom of the press are increasingly under threat.

Whitehall has shown it can brief against a government, for the most part discreetly and via former, retired, officials. Johnson became an increasingly safe target for them as they argued that all they were doing was defending constitutional propriety. A true test in future will be whether their loyalties in our democracy are not only to their political masters honouring those proprieties, but to us, the public. That means abandoning a culture of complacency and much less official secrecy. These must be a key test to judge their behaviour, as well as that of a new prime minister.