The UK press, from The Times to The Guardian, is also routinely helping to demonise states identified by the British government as enemies, while tending to whitewash those seen as allies.

The research, which analyses the UK national print media, suggests that the public is being bombarded by views and selective information supporting the priorities of policy-makers. The media is found to be routinely misinforming the public and acting far from independently.

This is the second part of a two-part analysis of UK national press coverage of British foreign policy.

Elite platform

Numerous stories or points of information on Britain’s intelligence agencies, such as MI6 and GCHQ, are being fed to journalists by anonymous “security sources” – often military or intelligence officials who do not want to be named.

The term “security sources” has been mentioned in 1,020 press articles in the past three years alone, close to one a day. While not all of these relate to UK sources, it indicates the common use of this method by British journalists.

Declassified’s recent research found that officials in the UK military and intelligence establishment had been sources for at least 34 major national media stories that cast Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn as a danger to British security. The research also found 440 articles in the UK press from September 2015 until December 2019 specifically mentioning Corbyn as a “threat to national security”.

Anonymous sources easily push out messages supportive of government policy and often include misleading or unverifiable information with no come-back from journalists. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) says it has 89 “media relations and communications” officers.

Many journalists regularly present the views of the MOD or security services to the public with few or no filters or challenges, merely amplifying what their sources tell them. In “exclusive” interviews with MI6 or MI5, for example, journalists invariably allow the security services to promote their views without serious, or any, scepticism for their claims or relevant context.

That the UK intelligence services are regularly presented as politically neutral actors and the bearers of objective information is exemplified in headlines such as “MI6 lays bare the growing Russian threat” (in the Times) and “Russia and Assad regime ‘creating a new generation of terrorists who will be threat to us all’, MI6 warns” (in the Independent).

Press coverage of the RAF’s 100th “birthday” in 2018 produced no critical articles that could be found, with most being stories from the MOD presented as news. This is despite episodes in the RAF’s history such as the bombing of civilians in colonial campaigns in the Middle East in the 1920s, 1930s and 1950s and its prominent current role in supporting Saudi airstrikes in Yemen, which has helped create the world’s biggest humanitarian disaster.

Similarly, for GCHQ’s 100th anniversary in 2019, the press appeared to simply write up information provided by the organisation. Only the occasional article mentioned GCHQ’s role in operating programmes of mass surveillance while its covert online action programmes and secret spy bases in at least one repressive Middle East regime were ignored by every paper at the time, as far as could be found.

The national press are generally strong supporters of the security services and the military. A number of outlets, from the Times and Telegraph to the Mirror, are strongly opposed to government cuts in parts of the military budget, for example.

The British army’s main special forces unit, the SAS, which is currently involved in seven covert wars, is invariably seen positively in the national press. A search reveals 384 mentions of the term “SAS hero” in the UK national press in the past five years – mainly in the Sun, but also in the Times, Express, Mail, Telegraph and others.

Critical articles on the special forces are rare, and the journalists writing them can face a backlash from other reporters.

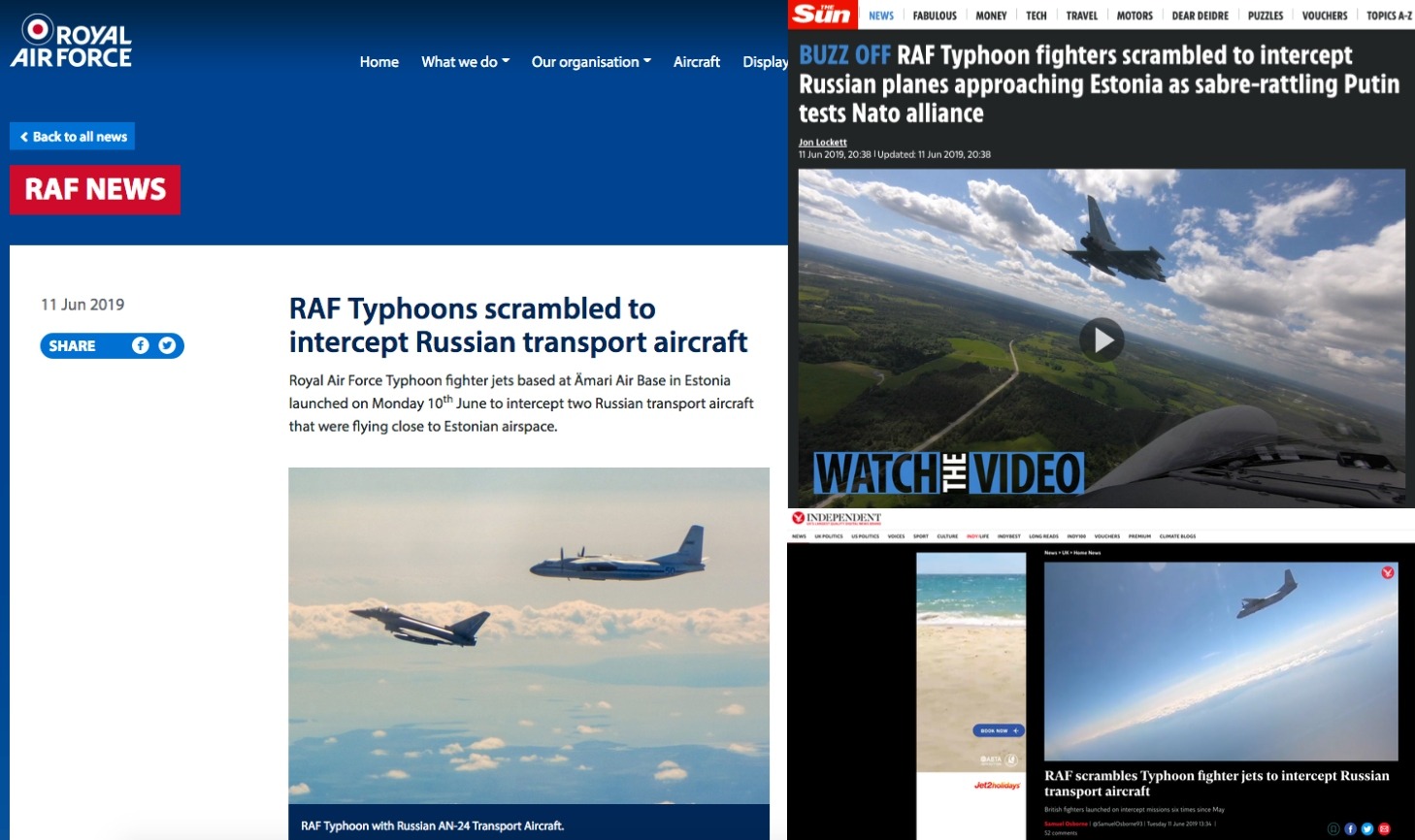

In some press articles, MOD media releases are largely copied and pasted. For example, recent MOD material on RAF Typhoons in Eastern Europe scrambling to intercept Russian aircraft has often been repeated word for word across the media.

Such “embedded journalism” poses a significant threat to the public interest. Richard Norton-Taylor, formerly the Guardian’s security correspondent for over 40 years, told Declassified: “Embedded journalists — those invited to join British military units in conflict zones — are at the mercy of their MOD handlers at the best of times. Journalists covering defence, security and intelligence are far too deferential and indulge far too much in self-censorship”.

Some papers are more extreme than others in their willingness to act as platforms for the military and intelligence establishment. The Express may well be the most supportive: its coverage of MOD stories and vilification of official enemies, notably Russia, is remarkable and consistent.

The Guardian, however, has also been shown to play a similar role. Declassified’s recent analysis, drawing on newly released documents and evidence from former and current Guardian journalists, found that the paper has been successfully targeted by security agencies to neutralise its adversarial reporting of the “security state”.

Censorship by omission

Articles critical of the Ministry of Defence or security services are occasionally published in the press. However, these tend to be either on relatively minor issues or are reported on briefly and then forgotten. Rarely do seriously critical stories receive sustained coverage or are widely picked up across the rest of the media.

Often, reporters will cover a topic and elide the most important information for no clear reason. For example, there is considerable coverage of possible MI5 failures to prevent the May 2017 Manchester terrorist bombing — failings which may be understandable given the large number of terrorist suspects being monitored at any one time.

However, the government admitted in parliament in March 2018 that it “likely” had contacts with two militant groups in the 2011 war in Libya for which the Manchester bomber and his father reportedly fought at the time, one of which groups the UK had covertly supported in the past. This significant admission in parliament has not been reported in any press article, as far as can be found.

Last September, veteran investigative journalist Ian Cobain broke a story on the alternative news site Middle East Eye revealing that the senior Twitter executive with editorial responsibility for the Middle East is also a part-time officer in the British army’s psychological warfare unit, the so-called 77th Brigade.

This story was picked up by a few media outlets at the time (including the Financial Times, the Times and the Independent) but our research finds that it then went unmentioned in the hundreds of press articles subsequently covering Twitter.

Similarly, in November 2018, a story broke on a secretive UK government-financed programme called the Integrity Initiative, which is ostensibly a “counter disinformation” programme to challenge Russian information operations but was also revealed to be tweeting messages attacking Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn.

Our research finds that in the 14 months until December 2019, the Integrity Initiative was mentioned less than 20 times in the UK-wide national press, mainly in the Times (it was also mentioned 15 times in the Scottish paper, the Sunday Mail).

By contrast, when stories break that are useful to the British establishment, they tend to receive sustained media coverage.

Establishment think tanks

The British press routinely chooses to rely on sources in think tanks that largely share the same pro-military and pro-intervention agenda as the state.

The two most widely-cited military-related think tanks in the UK are the London-based Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) and the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) which are usually quoted as independent voices or experts. In the last five years, RUSI has appeared in 534 press articles and IISS in 120.

However, both are funded by governments and corporations. RUSI, which is located next door to the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall, has funders such as BAE Systems, the Qatar government, the Foreign Office and the US State Department. IISS’s chief financial backers include BAE Systems, Raytheon, Lockheed Martin and Airbus.

This funding is mentioned in only two press reports that could be found – the Guardian reported that IISS received money from the regime in Bahrain while the Times once noted, “RUSI, while funded in part by the MoD, is an independent think tank”.

One Telegraph article refers to a “research fellow at RUSI who specialises in combat airpower”, without mentioning that its funder BAE Systems is a major producer of warplanes.

Although many senior figures in these organisations previously worked in government, press readers are rarely informed of this. RUSI’s chair is former foreign secretary William Hague, its vice-chair is former MI6 director Sir John Scarlett and its senior vice-president is David Petraeus, former CIA director.

The IISS’s deputy secretary-general is a former senior official at the US State Department while its Middle East director is a former Lieutenant-General in the British army who served as defence senior adviser to the Middle East. One of IISS’ senior advisers is Nigel Inkster, a former senior MI6 officer.

Media and intelligence

Richard Keeble, professor of journalism at the University of Lincoln, has noted that the influence of the intelligence services on the media may be “enormous” and the British secret service may even control large parts of the press. “Most tabloid newspapers – or even newspapers in general – are playthings of MI5”, says Roy Greenslade, a former editor of the Daily Mirror who has also worked as media specialist for both the Telegraph and the Guardian.

David Leigh, former investigations editor of the Guardian, has written that reporters are routinely approached and manipulated by intelligence agents, who operate in three ways: they attempt to recruit journalists to spy on other people or go themselves under journalistic “cover”, they pose as journalists in order to write tendentious articles under false names, and they plant stories on willing journalists, who disguise their origin from their readers — known as black propaganda.

MI6 managed a psychological warfare operation in the run-up to the Iraq war of 2003 that was revealed by former UN arms inspector Scott Ritter. Known as Operation Mass Appeal, this operation “served as a focal point for passing MI6 intelligence on Iraq to the media, both in the UK and around the world. The goal was to help shape public opinion about Iraq and the threat posed by WMD [weapons of mass destruction]”.

Various fabricated reports were written up in the media in the run-up to the Iraq war, based on intelligence sources. These included cargo ships said to be carrying Iraqi weapons of mass destruction (covered in the Independent and Guardian) and claims that Saddam Hussein killed his missile chief to thwart a UN team (Sunday Telegraph).

More recent examples of apparently fabricated stories in the establishment media include Guardian articles on the subject of Julian Assange. The paper claimed in a front page splash written by Luke Harding and Dan Collyns in November 2018 that former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort secretly met Assange in the Ecuadorian embassy three times.

The Guardian also falsely reported on a “Russia escape plot” to enable Assange to leave the embassy for which the paper later gave a partial apology. Both stories appeared to be part of a months-long campaign by the Guardian against Assange.

Demonising enemies

The media plays a consistent role in following the state’s demonisation of official enemies. The term “Russian threat” is mentioned in 401 articles in the past five years, across the national press. The Express may be the largest press amplifier of the government’s demonisation of Russia — the paper carries a steady stream of stories critical of Russia and Putin.

The British establishment has invoked Russia as an enemy in recent years due mainly to the poisonings in the town of Salisbury and policy in eastern Europe. Whatever malign policies Russia is promoting, which can be real, false or exaggerated, it is noteworthy that this has been elevated by the press to a general “threat” to the UK. As during the cold war, this is useful to the British military and security services arguing for larger budgets and for offensive military postures in Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Russia’s alleged interference in British politics has received huge coverage compared to alleged Israeli influence. A simple comparison of search terms using “Russia/Israel and UK and interference” in press articles in the past five years yields seven times more mentions of Russia than Israel, despite considerable evidence of Israeli interference.

UK press reporting on Iran is also noticeably supportive of government policy. A search for “Iran and nuclear weapons programme” reveals 325 articles in the past five years. While this large coverage is driven by president Trump’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, it is also driven by Iran being a designated enemy of the US and UK, which have deemed it unacceptable that Tehran should ever acquire nuclear weapons.

By contrast, “Israel’s nuclear weapons” (and variants of this search term) are mentioned in under 30 press articles in the past five years. Natanz, Iran’s main nuclear arms facility, has been mentioned in around four times more press articles than Dimona, the Israeli nuclear site, in the past five years.

The contrast in reporting on Iran and Israel is striking since Iran does not possess nuclear weapons, and it is not certain that it seeks to, whereas Western ally Israel already has such weapons, estimated at around 80 warheads.

Labelling goodies and baddies

The national press strongly follows the government in labelling states as enemies or allies.

States favoured by the UK are mainly described in the press using the neutral term “government” rather the more critical term “regime”. In the past three years, for example, the term “Saudi government” has been used in 790 articles while “Saudi regime” is mentioned in 388. However, with Iran the number of instances is reversed: “Iranian government” is used in 419 articles whereas “Iranian regime” is mentioned in 456.

The same holds for other allies. The “Egyptian regime” receives 24 mentions while “Egyptian government” has 222, in the past three years. The “Bahraini regime” is mentioned in 10 articles while “Bahraini government” is mentioned in 60.

The precise term “Iranian-backed Houthi rebels”, referring to the war in Yemen, is mentioned in 198 articles in the last five years. However, the equivalent term for the UK backing the Saudis in Yemen (using search terms such as “UK-backed Saudis” or “British-backed Saudis”) appears in just three articles.

The pattern is also that the crimes of official enemies are covered extensively in the national press but those of the UK and its allies much less so, if at all.

Articles mentioning “war crimes and Syria” number 1,527 in the past five years compared to 495 covering “war crimes and Yemen”. While the press often reports that the Syrian government has carried out war crimes, most articles simply suggest or allege war crimes by the Saudis in Yemen.

Indeed, the UK press has been much more interested in covering the Syrian war—chiefly prosecuted by the UK’s opponents—than the Yemen war, where Britain has played a sustained widespread role. As a basic indicator, the specific term “war in Syria” is mentioned in well over double the number of articles as “war in Yemen” in the past five years.

Furthermore, government enemies are regularly described in the press as supporters of terrorism, which rarely applies to allies.

In the past three years 185 articles mention the term “sponsor of terrorism”, most referring to Iran, followed by Sudan and North Korea with the occasional mention of Libya and Pakistan. None specifically label UK allies Turkey or Saudi “sponsors of terrorism”, despite evidence of this in Syria and elsewhere, and none describe Britain or the US as such.

Some 102 articles in the past five years specifically mention Russia’s “occupation of Crimea”. However, despite some critical articles on UK policy towards the Chagos Islands in the Indian ocean—which were depopulated by the UK in the 1970s and which the US now uses as a military base—only two articles specifically mention the UK’s “occupation of Chagos” (or variants of this term).

Similar labelling prevails on opposition forces in foreign countries. Protesters in Hong Kong are routinely called “pro-democracy” by the press – the term has been mentioned in hundreds of articles in the past two years. However, protesters in UK allies Bahrain and Egypt have been referred to as “pro-democracy” in only a handful of cases, the research finds.

The special relationship

While demonising enemies, UK allies are regularly presented favourably in the press. This is especially true of the US, the UK’s key special relationship on which much of its global power rests. US foreign policy is routinely presented as promoting the same noble objectives as the UK and the press follows the US government line on many foreign policy issues.

The term “leader of the free world” to refer to the US has been used in over 1,500 articles in the past five years, invariably taken seriously across the media, without challenge or ridicule.

The view that the US promotes democracy is widely repeated across the press. A 2018 editorial in the Financial Times, written by its chief foreign affairs commentator Gideon Rachman, notes that, “Leading figures in both [US political] parties — from John Kennedy to Ronald Reagan through to the Bushes and Clintons — agreed that it was in US interests to promote free-trade and democracy around the world”. In 2017 Daniel McCarthy wrote in the Telegraph of “two decades of idealism in US foreign policy, of attempts to spread liberalism and democracy”.

It is equally common for the UK press to quote US figures on their supposed noble aims, without challenge. For example, the Sunday Times recently cited without comment the US state department saying “Promoting freedom, democracy and transparency and the protection of human rights are central to US foreign policy”.

The press often strongly criticises President Donald Trump, but often for betraying otherwise benign US values and policies that it assumes previous presidents have promoted. For example, Tom Leonard in the Daily Mail writes of “Mr Trump’s belief that US foreign policy should be guided by cold self-interest rather than protecting democracy and human rights”.

The Guardian is especially supportive of US foreign policy. A sub-heading to a recent article notes: “The US once led Western states’ support of democracy around the world, but under this president [Trump] that feels like a long time ago”. One of its main foreign affairs columnists, Simon Tisdall, recently wrote that the US fundamental “mission” was an “exemplary global vision of democracy, prosperity and freedom”, albeit one which has been distorted by the war on terror.

The Guardian regularly heaped praise on president Obama. An editorial in January 2017 commented that Obama was a “successful US leader” and that “internationally” his vision “could hardly be faulted for lack of ambition”. It also noted Obama’s “liberalism and ethics” and that: “Mr Obama has governed impeccably for eight years without any ethical scandal”.

Although the article noted US wars and civilian casualties in Yemen and Libya, the paper brushed these off, stating “But to ascribe the world’s tragedies to a single leader’s choices can be simplistic. The global superpower cannot control local dynamics”.

Research covered the period to the end of 2019 using the media search tool, Factiva. It analysed the “mainstream” UK-wide print media (dailies and Sundays) over different time scales, usually two or five years, as specified in the article. Media search engines cannot be guaranteed to work perfectly so additional research was sometimes undertaken.