Now the International Court of Justice has ruled that Israel is “plausibly” promoting genocide in Gaza, the International Criminal Court might be expected to expedite its prosecution of the individuals responsible.

Israel’s war crimes and incitements to genocide in Gaza are being documented by independent legal groups.

The ICC itself, which is based in The Hague, has stated that, amid sustained attacks by Israel on Gaza, its investigation into the State of Palestine Situation is “ongoing”.

ICC prosecutor Karim Khan added that this “extends to the escalation of hostilities and violence since the attacks that took place on 7 October 2023” – when Hamas attacked Israel.

But nearly four months after this statement last November, no arrest warrants have been issued or, apparently, other actions taken by the ICC.

It was perhaps no surprise, therefore, that in December a number of Palestinian human rights groups refused to meet with Khan, who was on a visit to the region. They accused him of bias in favour of Israel.

Nominated by UK

Khan, a British barrister, was the UK’s nominee for ICC prosecutor, though he was not initially shortlisted. His appointment, in February 2021, was mired by controversies over how the election was organised.

When news broke that he was to be the next ICC prosecutor, the Economist commented that the Conservative government was “cock-a-hoop” over his appointment. Khan’s election “was surely a sign that Britain still had diplomatic heft”, it wrote.

The Foreign Office noted that the appointment of Khan was one of its “key achievements” in 2020/21.

Khan had extensive international legal experience before joining the ICC, including serving as a special adviser at the UN investigating the crimes of Islamic State in Iraq.

As a lawyer in London during 2000-10 Khan prosecuted criminal cases at the Bar, and was included on the “Old Bailey list” to prosecute the most serious offences at the Central Criminal Court.

He acted for the home secretary and for other applicants in numerous immigration and refugee law cases.

With Khan as prosecutor, the ICC has demonstrated it can act quickly when it needs to. In February 2022, for example, as Russia invaded Ukraine, Khan announced the ICC had opened an investigation into alleged Russian war crimes.

In September 2022 Khan met then foreign secretary James Cleverly and Ukrainian prosecutor general Andriy Kostin in regard to the situation in Ukraine.

A month later Cleverly met Khan again to discuss further how “the UK led 42 other countries in expediting an investigation into the situation in Ukraine.”

Five months later, in March 2023 the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Funding

Could Khan’s apparent slowness in taking forward cases against Israel be explained by not wanting to bite the hand that feeds his office?

The UK government has been one of the largest financial contributors to the court. It has provided the organisation with £10.5m to its latest annual budget and a further £2m since the commencement of Russia’s attacks on Ukraine.

The ICC’s overall budget for this year is around £160m.

Khan has a family connection to the UK Conservative Party via his brother Imran Ahmad Khan, an MP who in 2022 was found guilty of sexually assaulting a 15 year old boy. He was subsequently expelled from the party and sentenced to 18 months imprisonment.

ICC changes

A few months after his appointment, in November 2021, Khan announced to the United Nations Security Council that he intended to limit the ICC’s investigations to those referred to his office by that Council, whose permanent members include the UK and US.

Investigations that were not referred in this way would be placed under review. These included those into Afghanistan and Palestine that were conducted by his predecessor, Fatou Bensouda.

Why did Khan initiate these major changes to how the ICC works? The answer may lie with the UK and the United States.

A few years earlier, in December 2017 Bensouda announced that: “The [prosecutor’s] office has reached the conclusion that there is a reasonable basis to believe that members of the UK armed forces committed war crimes within the jurisdiction of the court against persons in their custody.”

The accusation referred to the conduct of the UK military in Iraq and would undoubtedly have displeased UK authorities.

US war crimes

Although the US (and Israel) is not a member of the ICC, Afghanistan ratified the Rome Statute that underpins the Court. So in 2016 the ICC commenced an investigation into alleged war crimes by the US military in Afghanistan.

Bensouda found that: “War crimes of torture and related ill-treatment, by US military forces deployed to Afghanistan and in secret detention facilities operated by the Central Intelligence Agency, principally in the 2003-2004 period, although allegedly continuing in some cases until 2014”.

That would have displeased US authorities.

Subsequently, in 2018 Washington issued a threat to arrest ICC judges should they attempt to charge US army personnel for war crimes.

Moreover, National Security advisor John Bolton warned that the US would ban “its [ICC] judges and prosecutors from entering the United States. We will sanction their funds in the US financial system, and we will prosecute them in the US criminal system.”

Undaunted, in December 2019 Bensouda announced she was satisfied that “war crimes have been or are being committed in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip”.

No doubt the US was concerned that Bensouda’s investigations could see its ally Israel facing prosecutions.

So it was that in September 2020 the US applied sanctions against Bensouda and her colleagues. The US also revoked her visas and visas for other senior ICC individuals.

But in January 2021, with Bensouda’s imminent departure from the post, US president Joe Biden announced that Washington would review its earlier decision to impose sanctions on the Court’s officials.

The following month Khan was appointed ICC prosecutor, and took up the role in June 2021 when Bensouda left.

Genocide playing out

If the ICC acts on its remit, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and other senior figures in Israel would be at risk of arrest. Arguably the same goes for Biden and UK prime minister Rishi Sunak – both of whom allow Netanyahu to conduct his genocidal mission with impunity.

In the wake of the Hamas attack on Israelis on 7 October and the response by Israel against the people of Gaza, Sunak made his bias crystal clear. In those early days in the conflict, and ever since, he stated, without caveats, that Israel had his full support.

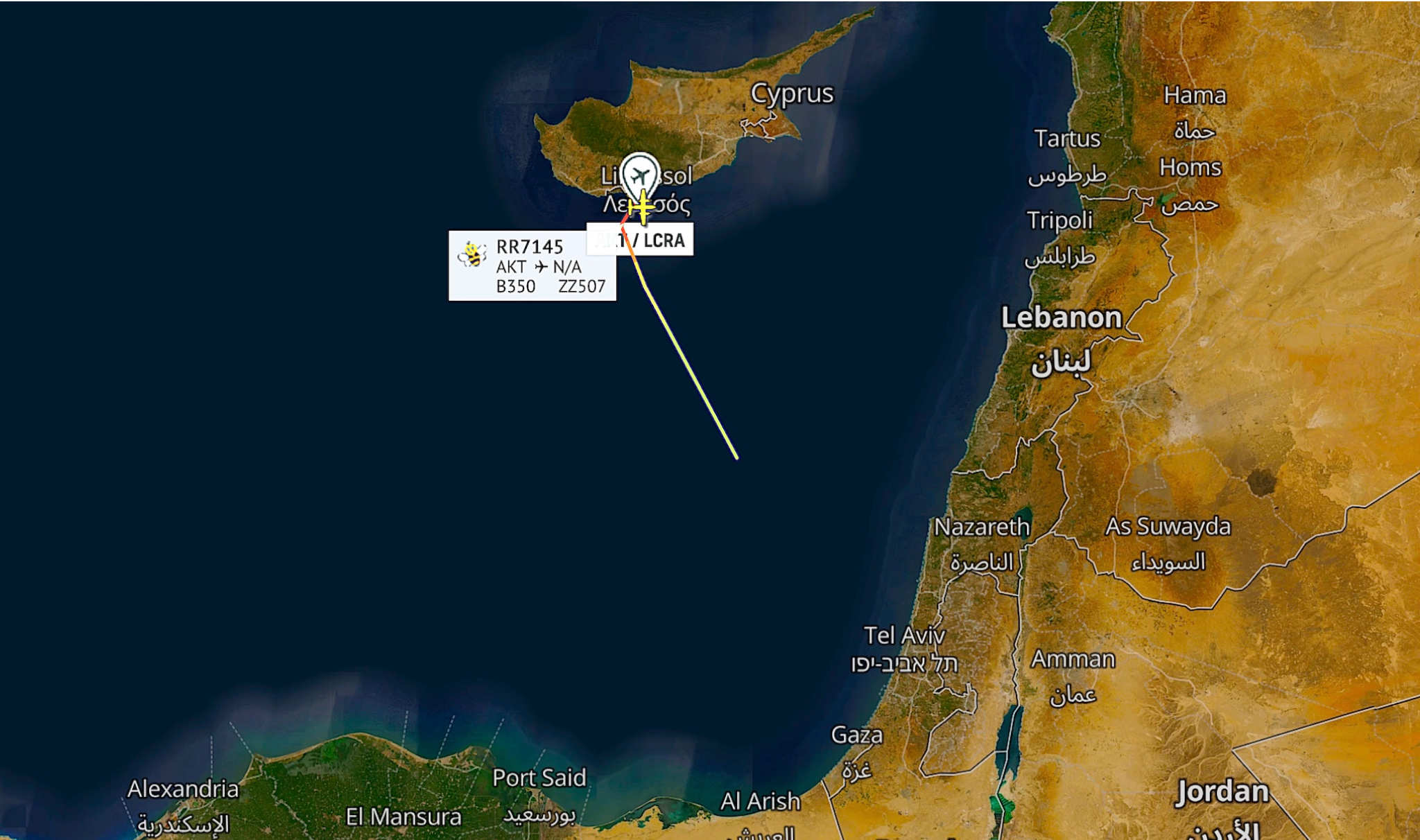

The UK is providing military and intelligence support to Israel.

Sunak and colleagues were warned by Tory veteran Crispin Blunt MP that they could face prosecution for their collusion in Netanyahu’s war crimes. Indeed, the International Centre of Justice for Palestinians (ICJP) has issued a notice of intent to prosecute UK government officials who have aided the commission of war crimes in Gaza.

Had the ICC been allowed to continue with its investigations into Palestine in 2019, it’s possible the genocide we are now witnessing in Gaza may not have taken place.

Khan speaks eloquently about the tragic events taking place there, though to say he is short on delivery is an understatement.

Just how many more men, women and children must die in Gaza before the ICC takes substantial action against those responsible?