- Repressive new law was praised by foreign secretary Malcolm Rifkind as an ‘important development’ and by UK officials as a ‘welcome first step’

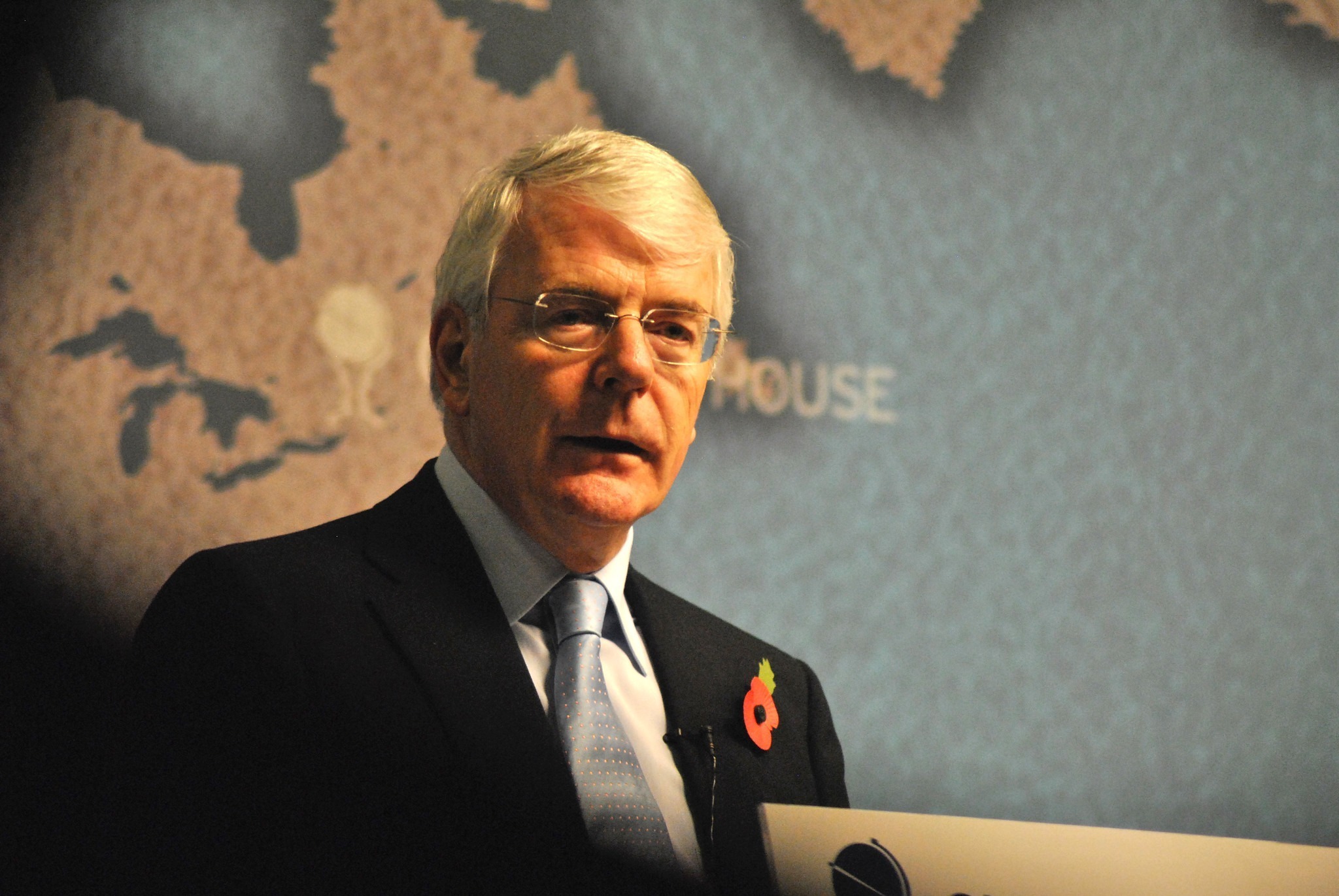

- John Major congratulated Qaboos, telling him ‘our commitment to Oman is unwavering’

- Revelations come a year after Qaboos died, amid a debate over political ‘reforms’ announced by his successor

Newly declassified Foreign Office papers shed fresh light on the extent of Whitehall’s support for Qaboos bin Said al-Said, who became Sultan of Oman in 1970 after deposing his father in a coup led by British soldiers.

The files show that British ministers and officials welcomed the introduction of a repressive Basic Law in 1996 amid efforts to secure arms and energy contracts with the regime.

Following the coup, Sultan Qaboos ruled Oman for half a century until his death a year ago this week, by which time he was the Middle East’s longest-serving dictator. For the first two decades of his rule, Qaboos used British troops and mercenaries to suppress armed left-wing opponents in Dhofar, southern Oman.

Following their complete defeat, Qaboos allowed security-vetted independent candidates to run for a powerless consultative assembly in 1991. However, unrest resurfaced in 1994 when hundreds of alleged Muslim Brotherhood members were arrested over an alleged plot to take power.

In 1995, Qaboos was nearly killed in a car crash, in what some believe was a failed assassination attempt. By the mid-1990s, British diplomats had “misgivings” about Qaboos’s lack of any formal succession plans, worrying that such uncertainty could deter UK companies from investing in Oman.

Recently declassified papers show that British officials felt Qaboos, who had no direct descendants, was “risking the stability of Oman by failing to look to the future.” These concerns were addressed in November 1996 when Qaboos issued a royal decree introducing a “basic law, effectively Oman’s first written constitution”.

“Its provisions answer some of the major issues of concern about Oman’s future which had been raised by bankers and investors,” wrote a British official. “It should provide a welcome boost to the confidence of international investors in the future of the Omani market.”

The highly oppressive law decreed Oman’s “system of government is a hereditary Sultanate in which succession passes to a male descendant” of Qaboos. Article 48 set out that “If the Sultan appoints a prime minister, his competencies and powers shall be specified in the Decree”. Ultimately, Qaboos appointed himself as prime minister.

Under the law, it was “forbidden to establish associations whose activities are inimical to social order”, effectively banning political parties or groups critical of Qaboos, whose status was enshrined as “inviolable and must be respected.” Meanwhile, journalists were “prohibited to print or publish material that leads to public discord.”

‘Unwavering support’

Although British diplomats noted that “the law raises nearly as many questions as it answers”, they praised it as a “welcome first step” towards reform by the Sultan, who had already spent a quarter-century in power.

One UK official, Dominick Chilcott, who is now ambassador to Turkey, wrote, “It shows that the Sultan remains attuned to criticism, by addressing the weaknesses in the political and economic systems identified by Oman’s allies and foreign investors.”

Foreign secretary Malcolm Rifkind regarded it as an “important development which merits a message” from Britain’s then prime minister John Major, who congratulated Qaboos in a letter.

Major commended the basic law as “clearly a most imaginative and constructive step forward”, assuring Qaboos that “our commitment to Oman is unwavering” and hailing the legislation as a “significant stage in Oman’s development … clarifying the guarantees of rights and freedoms.”

Major claimed that it “confirmed the separation of the executive and the judiciary”, despite Qaboos giving himself the power to appoint ministers and dismiss senior judges. Qaboos was commended for “giving further thought to the development of the Majlis al-Shura”, Oman’s powerless consultative assembly from which political parties were (and remain) banned.

Foreign Office papers show Qaboos welcomed “the nice things the Prime Minister had said about the new law.” The legislation was later praised in Foreign Affairs magazine, which described the basic law as a “revolutionary…bill of rights.”

In a rare interview, Qaboos told the US publication that “change had to be entered into slowly, very slowly”. When asked if he would hold democratic elections for his own position, the Sultan claimed he was “already elected, but not in the way you know.”

Qaboos’ reforms had no impact on the Polity IV index, a widely used empirical measure of political regimes, which continued to rank Oman at minus nine – the second most autocratic rating available. This score kept Oman on par with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and ranked it as less democratic than Colonel Gaddafi’s Libya or Ayatollah Khamenei’s Iran.

Reacting to Major’s comments, Nabhan al-Hanashi, a political exile and chairman of the Omani Centre for Human Rights, told Declassified: “I’m not surprised as Qaboos was always their loyal servant in the Arabian Peninsula, but I question how a prime minister of a democratic country supported such an arbitrary law, whilst claiming to believe in democracy and human rights?”

Arms and oil deals

The revelations come as the new Sultan of Oman, Qaboos’s nephew Haitham, is announcing changes to the basic law. Haitham’s political reforms include creating the role of Crown Prince as heir to the throne.

State-controlled media in the Gulf has hailed the move as a “constitutional overhaul”, although it appears that the Crown Prince will be Haitham’s eldest son, suggesting that the aim is to further reduce any doubts about the line of succession.

Al-Hanashi told Declassified: “The new Basic Law is another copy of the previous one. Most other articles are not new and were stated in the previous version. Haitham does not seem to be considering human rights or freedoms.”

Haitham has pledged to set up a committee to monitor the performance of ministers, in a supposed transparency and anti-corruption drive. There are long-standing concerns in Oman about ministers taking bribes on major contracts.

The newly declassified UK file from the mid-1990s shows that the discussions over Oman’s original basic law took place amid efforts by Downing Street to ensure British energy and arms companies won lucrative contracts in Oman.

British companies had a 70% share of Oman’s defence market, with tanks and armoured vehicle contracts on the table worth more than £200-million. John Major played an active role in these discussions, urging Qaboos in a letter to upgrade his fleet of British-made Jaguar jet planes.

Meanwhile, British oil giant BP won a contract to build a petrochemicals plant in Sohar, northern Oman, after Major urged Qaboos to award the contract to the British firm. It was contrary to the advice of Omani ministers and came amongst competition for other deals from French and US firms — the latter backed by then-president Bill Clinton and former vice president Al Gore.

BP continues to have major investments in Oman, including what it calls the “giant Khazzan gas field”. BP owns a 60% stake in the gas field – a very high proportion by international standards – leaving the Omani state with just 40%.

British friends

A crucial factor for British firms to win contracts in Oman was that Qaboos was an anglophile who was “distinctly unimpressed by…US arrogance”, according to the declassified papers. One of the Sultan’s closest aides was Sir Erik Bennett, a Royal Air Force (RAF) officer who had advised the King of Jordan.

Bennett became commander of Oman’s air force in 1974 during the Dhofar uprising, a role he held until 1990 whereupon he was knighted in the UK. After retiring from the RAF in 1991, Bennett became an adviser to Qaboos and was injured in the car crash in 1995.

Little is known about his time as an adviser, apart from the newly released file which shows Bennett continued to play an active role on behalf of the Sultan. He accompanied Britain’s Chief of the Defence Staff, Field Marshal Peter Inge, and Conservative MP Jonathan Aitken, on a trip to Oman for New Year’s Eve in December 1996, shortly after Qaboos issued the Basic Law.

Around the time of the trip, Aitken, a former defence procurement minister, was suing journalists for libel over allegations he was embroiled in corrupt arms deals with Saudi Arabia. Six months after visiting Oman, he had lost his seat in parliament as well as the libel action and was eventually jailed for perjury.

When asked about his trip to Oman, Aitken, who is now a priest, told Declassified that Sultan Qaboos “used to make a big thing at New Year’s Eve of having a rather special kind of Anglophile long weekend. It was a great New Years Eve party and I stayed in his palace which was extremely comfortable.

“The point of it was really to be conversationally intimate with a few chosen Brits and the chief chosen Brit was Air Vice-Marshal Sir Erik Bennett who was a sort of special advisor to the Sultan and had been for many years. [Bennett was] frightfully good with the Sultan and a real friend.”

Aitken said his own access to Qaboos came about “really because of a rather strange link”, as he grew up in Suffolk where he had known a teacher that tutored the young Sultan at a private school in the eastern English county.

Aitken added, “It wasn’t the only time I’d been to a New Year’s Eve party [in Oman]. I’d been at least three or four times before. But the Sultan just really liked to roam around conversationally in a trusted environment and felt that he could trust the Brits at a certain level.

“I’m not sure we ever did anything very exciting, but we certainly enlarged the area of confidence in which conversations could take place with the head of state. Like any kind of good weekend, there were a lot of wide-ranging conversations, a lot of jokes.

“The Sultan had quite a geopolitical mind. He was a strategic thinker, outside the Oman box to quite a big extent. He used to wonder what direction was Oman going in, what direction was Saudi Arabia going in, what’s happening in America, who is going to win the next election.

“The Sultan just liked to chew the fat, very elegantly with delicious dinners…He used to talk quite a bit about the special relationship between Britain and Oman, what was that, who had anything to do with it. The answer was the Sultan himself, of course, Erik Bennett, General Inge, one or two other people.”

The papers show that by 1997, Bennett was in a position to make “all the arrangements for official visits to the UK by Omani ministers”, creating tension among Whitehall officials who felt he was more powerful than British diplomats.

When Sultan Qaboos decided to go ahead with a major arms deal to purchase Challenger 2 tanks from British company Vickers Defence Systems, it was Bennett who called 10 Downing Street to deliver the news. He had lunch with Major’s private secretary, John Holmes, in February 1997, to emphasise “the Sultan’s commitment to Britain, and implicitly the important role played in this by Sir E Bennett.”

At the lunch, Bennett portrayed himself as part of an anti-corruption effort, reportedly telling the head of Vickers, Sir Colin Chandler, “to keep his cheque book in his pocket!” Chandler had previously sold arms to Saudi Arabia for British Aerospace in a deal that was mired by corruption.

Bennett continued to be an adviser to Qaboos until at least June 2012, when the pair attended a lunch at Buckingham Palace with the Queen and foreign secretary William Hague.

Another Conservative politician mentioned in the file who has close ties to Oman is Sir Alan Duncan, who brought “good wishes” to Sultan Qaboos in November 1996. Duncan, a former oil trader who stood down as an MP in 2019, served as David Cameron’s special envoy to Oman. He has visited Oman at least 24 times since 2000.

As a foreign minister in 2016, Duncan was targeted by an Israeli diplomat in London, Shai Masot, who plotted to “take down” the MP for speaking out against the building of Israeli settlements in the West Bank. The policy, which is illegal under international law, is heavily promoted by Israel’s right-wing prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In 2018, Qaboos sparked controversy when he met Netanyahu in Oman, despite the country having no diplomatic relations with Israel. The declassified UK file shows that in 1996 Qaboos was more hostile towards Tel Aviv, describing potential Israeli support for a new club of Middle Eastern countries as “the kiss of death, particularly when Netanyahu was proving such a disastrous Israeli leader.”

Sir John Major and the UK Foreign Office were asked for comment.