Kenya’s military privately rebuked their British counterparts over “lax” handling of ammunition years before it emerged that hundreds of civilians had been harmed by unexploded ordnance from UK army exercises.

As early as 1985, a Kenyan officer complained that “the British army is lax in their handling of ammunition and explosives”, according to a military report found by Declassified UK.

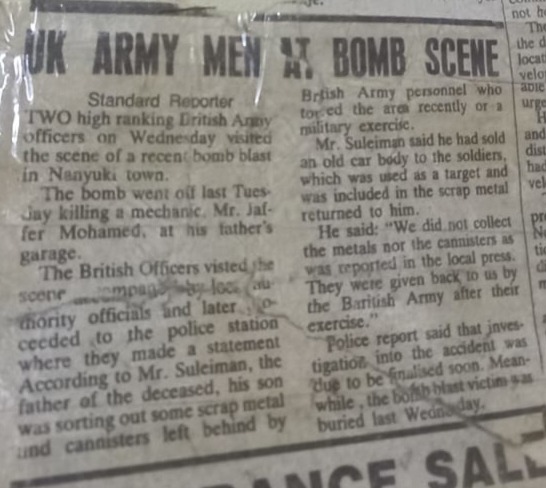

The unnamed officer registered his concern after a mechanic was blown up by British ordnance in Nanyuki, the garrison town 90 miles north of Nairobi where UK troops have a training camp.

The victim, 27-year-old Jaffer Mohamed, had a wife and four children. His eldest, Ali, is still traumatised from losing his dad at age nine. “When I see the British army in Nanyuki, I see my father dying,” he told Declassified.

Although Jaffer’s death was far from an isolated incident, it would take another two decades for the British military to publicly admit that more than a thousand Kenyans had been harmed by its unexploded ordnance (UXO).

These hazards are now being investigated by MPs as part of an inquiry into abuses by the British Army Training Unit Kenya (BATUK).

Committee chairman Nelson Koech has promised the probe will be thorough, saying: “Whether it dates back to [independence from Britain in] 1963, we have to get to the bottom of it.”

The evidence uncovered by Declassified UK suggests that much of the suffering could have been prevented decades ago had lessons been learnt from Jaffer Mohamed’s death in June 1985.

A long forgotten tragedy

“My father used to give the British army scrap vehicles to go and do artillery practice with,” Ali Mohamed said from his home in Nanyuki, where his family still runs a garage.

“When they finished the artillery firing they used to give the cars back and tell him he could keep the scrap,” Ali explained.

One day, the army gave the garage 900 shillings (equivalent to £130 today) to use a vehicle for target practice at Mpala, a ranch owned by a family of European settlers.

A formerly secret UK military report on the incident says the car was returned to the garage together with ammunition boxes, “contrary to [British army] standing orders”.

Jaffer was unaware of the danger. “He had no idea,” Ali said. “Because with scrap you only take metal and he was just dismantling the car to check the engine was there and see what he could sell as aluminium.”

“That’s when the blast happened,” Ali recalled. “There was something in there that hadn’t exploded on the firing range.”

Britain’s high commissioner, Leonard Allinson, said Jaffer “blew himself up by hammering a discarded mortar fuse, part of a scrap consignment.” An army report said: “The explosion was heard up to 2 miles away.”

Jaffer lost a hand and suffered severe stomach injuries before passing away soon afterward in Nanyuki hospital.

“I was with him that day,” Ali said. “It was Ramadan. We’d been fasting during the day. I came out of school and that’s when it happened, my father passed away.”

Ali still feels the loss. “It’s been terrible for us. Terrible. He was the one who was taking care of everyone in the family. He was my best friend.”

“He was young, handsome and good looking. My mum tells me I look just like my dad now,” Ali added, with a slight laugh.

His father’s death followed another mishap that year in which plastic explosives went missing from a British army exercise at Mpala.

This prompted a Kenyan military intelligence officer to tell UK officials: “Considering both incidents it seems that the British army is lax in their handling of ammunition and explosives”.

Norman Ling, a British diplomat, noted: “Our defence relations with Kenya have taken a knock in recent months, particularly over the Nanyuki incident in which a Kenyan Asian was killed by an explosion caused by ammunition left behind after a British army exercise.”

However others in authority did not express concern. Files state that Kenya’s chief of military intelligence “was very relaxed” about the death.

Quest for justice

After the explosion, Ali’s uncle had to take over running the garage and his grandfather, Suleiman Ali Mohamed, sought justice.

He instructed a lawyer in Nairobi and appeared willing to accept Sh850,000 (equivalent to £88,000 today) in compensation for the family.

A year after the death, Britain’s defence attaché Colonel Roger Southerst wrote: “We all admit we were responsible” but “sadly the affair still drags on”, blaming the claimant’s lawyer for inaction.

A commander from the UK army’s legal group visited Kenya in 1987 to review progress on the case. It was proposed they kick start negotiations at Sh600,000 (equivalent to £62,000 today).

However an official felt “it is useful for a claimant to be left to prosecute his own case” and hinted that they should “[let] sleeping dogs [lie]”.

It is unclear from the files seen by Declassified whether any payment was authorised. Ali is unsure if his grandfather, who has now passed away, ever received compensation.

Upon learning that Kenya’s parliament is holding an inquiry into the British army, Ali had mixed feelings. “I was 50/50. Because the years have passed too much and I can’t claim anything, and I can’t talk to anyone about it,” he lamented.

Martyn Day, the co-founder of London law firm Leigh Day which has worked on hundreds of similar cases, told Declassified: “The level of unexploded ordnance in the central Kenyan army range is very high indeed.

“We understand that some 10% of ordnance when fired do not explode and yet no effort seems to have been made to systematically clear the land following manoeuvres historically.”

He added: “The ranges, which are not fenced off from the public, are a terrible hazard to unsuspecting local people and the area should be cleaned up as a matter of great priority.”

Negligence

In 2002, litigation by Leigh Day forced the UK to award £4.5m in compensation to 228 Kenyan civilians bereaved or injured by UXO in blasts stretching back to the late 1970s.

Another round of payouts for more than a thousand claimants followed in 2004.

Despite these settlements, problems persisted and in 2007 a Kenyan man working for the British army was blown up by a plastic explosive. The victim, Robert Swara Seurei, mistook the device for a candle.

A UK defence minister admitted “inadequate” training practices “contributed” to his death. The case had strong similarities with Jaffer Mohamed’s death in 1985.

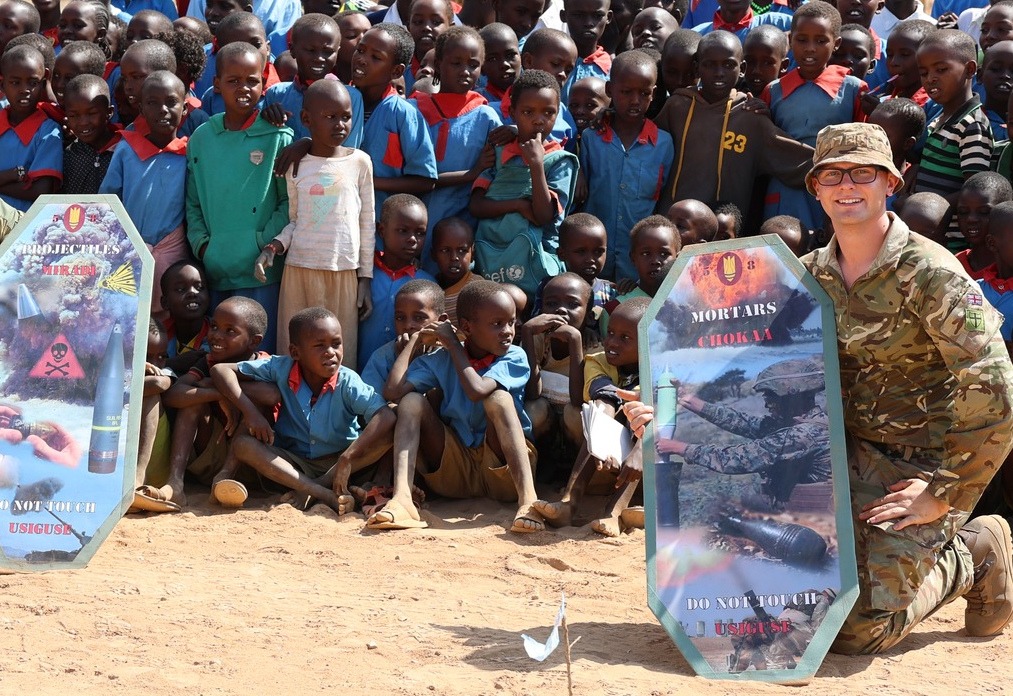

A further casualty occurred in 2015 when a 13-year-old Samburu boy, Lisoka Lesasuyan, picked up a mortar fuze. It detonated, costing him both arms and an eye.

An investigation found the British military knew the explosive used in the fuze was faulty before the accident took place. The type of ammunition has since been withdrawn from service.

More recently in 2021, another 13-year-old boy received burns after igniting a flare left behind by British troops near Archers Post.

Schools in that area, which is used for firing live ammunition and white phosphorus chemicals, told the Sunday Nation that children as young as seven have to be taught how to recognise unexploded bombs.

Britain also has a firing range in Canada, where their licence to operate is much stricter. A treaty governing that relationship explicitly requires the UK to “pay any reasonable cost associated with the removal or destruction of UXO at the training area”.

Author’s note: All conversions from Kenyan Shillings to Pounds Sterling in this article are approximate. Historical exchange rates have been taken from US Treasury data and adjusted to today’s value using the Bank of England’s inflation calculator.