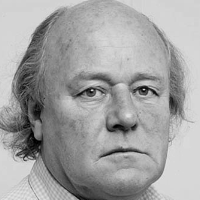

Former UK foreign secretary Sir Malcolm Rifkind said it was “highly improbable” that MI6 officers deliberately lied about their involvement in the surveillance and arrest in Kenya in 2010 of British terrorist suspect Michael Adebolajo.

He added: “It is not impossible that certain SIS officers were carrying out activities in Kenya that had not been authorised by London… My main reason for scepticism is that I cannot see what motive SIS would have had to lie to the ISC [Intelligence and Security Committee]… I do not see any credible motive for the chief of SIS, and his colleagues, to have lied to a statutory committee of Parliament.”

Rifkind was responding to evidence from Declassified that MI6 misled two government reviews into the intelligence services’ handling of the case of Adebolajo, who was released in the UK and went on to kill a British soldier, Lee Rigby, on the streets of London in May 2013.

Rifkind was the chair of the Intelligence and Security Committee that reviewed the case and took evidence from MI6. The ISC was set up in 1994 to appease those demanding scrutiny of Britain’s intelligence agencies and is composed of parliamentarians from the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Modest reforms over the years have led to some increases in the committee’s role and authority over the intelligence community. However, it remains subservient to the executive, it meets in private and its members are vetted by the prime minister, who decides what evidence should be censored and when its reports can be published.

Boris Johnson’s refusal to publish the ISC’s report on Russian attempts to interfere in British politics, including the EU referendum campaign, until well after the December 2019 general election, is a recent case in point.

As a former postholder, Rifkind must know how easy it has been for MI6 to conduct operations without the knowledge of its political boss, the foreign secretary, or even its own chief, as he is called (the agency has never had a female head), let alone the ISC.

‘You don’t know everything… the security services are doing’

MI6 repeatedly misled the ISC by denying its role in the abduction, rendition and subsequent torture, of suspected Islamist extremists.

In 2005, Jack Straw, one of Rifkind’s successors as foreign secretary, told the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee: “Unless we all start to believe in conspiracy theories and that the officials are lying, that I am lying, and that behind this there is some kind of secret state in league with some dark forces in the US… there is simply no truth in claims that the UK has been involved in rendition”.

That was more than a year after MI6 and the CIA, in a joint operation, rendered two opponents of Muammar Gaddafi to Tripoli were they were tortured by the Libyan dictator’s secret police.

When in 2011 that operation was revealed – thanks to journalists, not the ISC – Straw explained: “No foreign secretary can know all the details of what its intelligence agencies are doing at any one time.”

Tony Blair, the prime minister at the time of the Libya operation, told the BBC later that year: “You don’t know everything that is happening, that the security services are doing. I don’t know about them.”

When in 2018 the British government finally apologised for MI6 involvement in abduction and torture, the Attorney-General, Jeremy Wright, told MPs that “cultural” and “behavioural changes” as well as “system” changes were needed in Britain’s intelligence agencies.

MI6’s involvement in rendition operations so angered Eliza Manningham-Buller – the head of Britain’s domestic security service, MI5, from 2002-7 – when she heard about them that she told the agency’s officers to leave Thames House, MI5’s HQ, where they were conducting joint operations.

Ministers can mislead Parliament and the public about what intelligence officers have been up to because they often simply do not know. The heads of the agencies can also be kept in the dark. MI6 officers in the field enjoy huge freedom, as most recently demonstrated in the so-called “war on terror”.

Immune from prosecution

Revised guidance for intelligence officers, and the equally secretive “special forces”, has left open loopholes that can be exploited. A so-called “James Bond clause” – section 7 of the 1994 Intelligence Services Act – protects officers from prosecution for acts that would otherwise be illegal in British law.

The act states that in such cases, MI6 officers should first consult the foreign secretary. But evidence from Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as Libya, shows that officers on the ground sometimes do not even consult their head office in London, let alone ministers.

The report of the Gibson inquiry – set up in 2010 to investigate the UK’s role in CIA renditions and the handling of detainees – revealed that MI6 officers were told they were under no obligation to report breaches of the Geneva Conventions.

MI6 officers have long enjoyed the freedom to conduct operations without London knowing. Sometimes, they have been guided by nods and winks, as was the case in Northern Ireland when MI6 officers conducted back channel talks with the Irish Republican Army (IRA) – in the interest, in this case, of ending a violent conflict.

During the Cold War MI6 officers known as the “robber barons” conducted operations on a freelance basis.

The widely respected intelligence writer, Stephen Dorril, author of the book MI6, has described how a senior MI6 officer, George Kennedy Young, overrode Washington’s instructions to the CIA in Iran in 1953 to halt the coup to topple Mohammad Mosaddeq, Iran’s first democratically elected leader. Young refused to pass on the message and ordered his agents in Tehran – without reference to London – to go ahead. Young took the decision when Washington and the CIA were having second thoughts about the planned coup. MI6 officers had always been in the lead in organising and promoting it.

Evelyn Shuckburgh, a senior Foreign Office official at the time of the British invasion of Egypt in 1956 – often called the ‘Suez Crisis’ – observed: “You find that people in MI6 were conducting quite separate policies quite regardless of what the Foreign Office view was. I was astonished when somebody showed me some document written by an acquaintance of mine in MI6. I wouldn’t have recognised it all as being anything like British policy, but it was set out as being so. These secret people, you see, they get so above themselves, if I might say so.”

Gone rogue

In 2011, as the uprising against Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi was under way, MI6 officers took an interesting decision. In an operation to set up a meeting with anti-Gaddafi rebels, instead of using a British frigate stationed off the eastern coastal city of Benghazi as their base, they decided to ask a British special forces Chinook helicopter in Malta to drop them in the Libyan desert.

To the British government’s huge embarrassment, they were promptly captured by suspicious Libyans, taken to Benghazi and released only after frantic intervention by anxious British officials. Though the foreign secretary, William Hague, told MPs that he had authorised a covert mission to contact the rebels, London was unaware of the MI6 officers’ decision to ask special forces’ soldiers and their Chinook to drop them off, according to informed sources.

The Kenyan capital, Nairobi, is the home of a large MI6 station, perhaps the agency’s biggest in Africa. It is entirely possible that the chief of MI6 was unaware of what his officers were up to during the pursuit of Michael Adebolajo, one of those who later murdered Lee Rigby.

As Declassified reported, an ISC inquiry noted in 2014 that the British government may have been complicit in Adebolajo’s ill-treatment and criticised evidence from the former Chief of MI6, Sir John Sawers.

A new inquiry by Sir Mark Waller, the intelligence services commissioner, later reported that MI6’s level of engagement with two oversight investigations was “wholly inadequate” and “extremely unsatisfactory”.

The case of Gareth Williams, an officer with Britain’s signals intelligence agency, GCHQ– who was seconded to MI6 – is particularly telling about how MI6 has managed its officers.

In 2012, his dead body was found in a bag in his flat in London, an MI6 “safe house”. In a damning verdict, the coroner, Fiona Wilcox, accused MI6 officers of hampering the police investigation into Williams’ death. Wilcox told the inquest that the evidence given by Williams’ line manager at MI6 “begins to stretch the bounds of credibility”.

For more than a week, MI6 did not alert the police or get in touch with any member of his family. A senior MI6 officer referred to a “breakdown in communications”. Sawers apologised “unreservedly”.