- Queen ignored warnings that Sheikh Mohammed held his daughters hostage and gave him a horse racing award a year after one, Princess Latifa, had fled Dubai and been forcibly returned

- Queen billed the public £364,000 for flights to a Gulf country where its ruler gave her a golden egg and private horse show, months before the regime shot dead ‘Arab Spring’ protesters

- Omani anti-corruption activist was tortured for protesting against the sultan sending 110 horses to Queen’s Diamond Jubilee pageant

- Gulf activists who protested against Bahraini king attending the annual Windsor horse show with Queen Elizabeth have suffered retaliation

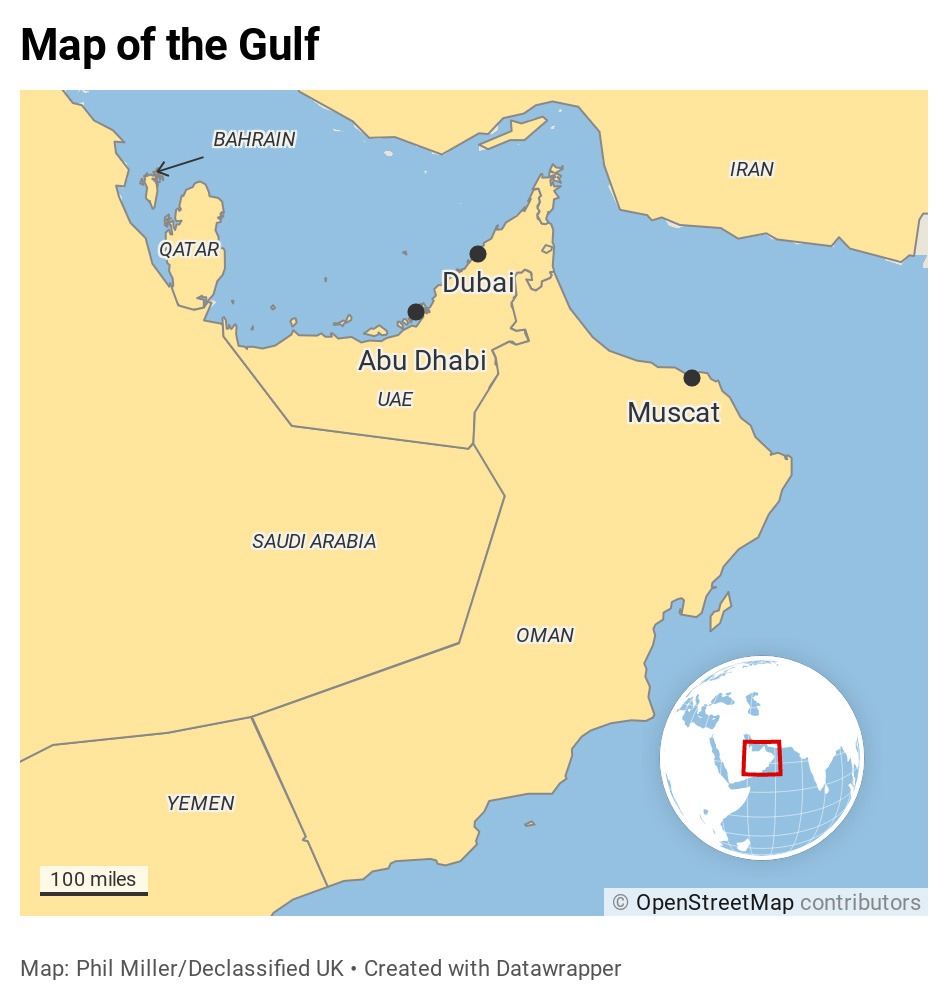

Queen Elizabeth has met with Middle Eastern monarchies dozens of times since the “Arab Spring” uprisings threatened their rule 10 years ago this month, research by Declassified UK has found.

Her love of horses has seen her keep close ties with some of the Gulf’s most repressive regimes over the past decade, despite repeated condemnations from human rights groups about their abuses.

Now the queen’s friendship with the ruler of Dubai is facing particular scrutiny after new evidence broadcast last week suggested one of his adult daughters is being arbitrarily detained.

Princess Latifa claims her father, 71-year-old horse-racing enthusiast Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, is holding her “hostage” in a locked villa in Dubai, the city state he rules in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Britain’s foreign secretary Dominic Raab said the footage of Princess Latifa is “deeply concerning”. The UAE claims she “is being cared for at home”.

The situation is highly embarrassing for the Queen, who has a long association with Sheikh Mohammed, despite claims from as far back as 2001 that he had orchestrated the kidnapping of another daughter, Princess Shamsa, in Cambridge, eastern England.

Shamsa was allegedly driven to a family property in the English horse racing town of Newmarket, tranquilised and forcibly returned on a private jet to Dubai. She has not been seen in public again.

Yet Sheikh Mohammed was able to maintain good relations with Queen Elizabeth and the pair gifted race horses to each other around 2010.

She met him during an official trip to the UAE, of which he is the vice-president, in November 2010, months before the Arab Spring.

The UAE used extensive surveillance powers to crack down hard on any pro-democracy activists, sentencing five activists to up to three years in prison for charges that included insulting the country’s leadership.

Among those convicted were the prominent blogger Ahmed Mansour and Dr Nasser bin Ghaith, an economics professor from Sorbonne university in Paris.

Such repression did not seem to put the queen off from meeting Sheikh Mohammed, who has been photographed with her on at least 10 occasions since the Arab Spring.

These included presenting him with the Gold Cup, a prestigious horse racing award, at Ascot in June 2012.

The following year she hosted a state visit from Sheikh Mohammed’s colleague, the UAE’s president and ruler of Abu Dhabi, Sheikh Khalifa. He was treated to a lavish lunch and stayed as a guest of the queen in Windsor Castle.

The UAE state visit came at a time when Whitehall was trying to secure arms sales for British companies worth billions, amid increased repression in the Emirates where a mass trial of 94 activists was under way.

The men were accused of ties to al-Islah, an offshoot of Egypt’s then ruling Muslim Brotherhood party which was advocating for political reform in the UAE.

Some 69 of the men were later convicted of attempting to overthrow the government, with sentences of up to 10 years imprisonment.

Their trial was marred by irregularities, including the jailing of Abdullah al-Hadidi, a citizen journalist who attempted to cover the court case on Twitter, a move which the media freedom group Reporters Without Borders called an “outrage”.

During the trial, the queen was seen celebrating the result of a horse race with Sheikh Mohammed at Ascot.

Over the next few years she would regularly meet him and his wife, 46-year-old Princess Haya – a sister of the King of Jordan and former Olympic equestrian competitor.

In November 2016 Princess Haya met Queen Elizabeth in Newmarket, the English town at the heart of Sheikh Mohammed’s horse racing empire known as Godolphin. There she unveiled a bronze statue of herself, which reportedly cost around £650,000 – most of it paid for by the ruler of Dubai.

By this point, the UAE was embroiled in a disastrous war in Yemen, where Emirati forces are alleged to run a network of torture chambers and black sites, in a bitter conflict that has now led to a quarter of a million deaths, mass hunger and disease.

The regime’s reputation took a further blow in March 2018 when it emerged that another of Sheikh Mohammed’s grown up children, Princess Latifa, then aged 33, had tried to flee Dubai on a private yacht.

Her vessel was allegedly raided in international waters off the coast of India by Emirati commandos and she was forcibly returned to the UAE and held incommunicado. Declassified has previously revealed that UAE commandos received training from Britain’s royal marines.

However, this second serious allegation about Sheikh Mohammed’s treatment of his daughters did not deter Queen Elizabeth from appearing with him in public at the Royal Windsor Horse Show in May 2018.

Their encounter came days after British academic Matthew Hedges had been arrested at Dubai airport and held on bogus spying charges, which carried up to life in prison.

The queen continued to spend more time with the ruler of Dubai, notably at the Epsom Derby festival in June 2018 and again at Ascot on 22 June 2019 when she presented a prestigious horse racing award to him.

A week after the Ascot award, news broke that Sheikh Mohammed’s wife Princess Haya was seeking a divorce and had claimed asylum in Germany.

Haya later won a high court case in London against her husband, who was found to have kidnapped Shamsa and Latifa, finally prompting the queen to say she would no longer be photographed in public with him.

Last week new video evidence emerged that Princess Latifa is being held by police at a secure villa in Dubai, raising fresh concern about the queen’s long association with her father.

Declassified asked Buckingham Palace whether the queen regrets not distancing herself sooner from Sheikh Mohammed, and why she continued to meet him despite allegations of abuse from 2001.

A Buckingham Palace spokesperson said: “Official engagements with other heads of state are undertaken on the advice of government. We do not comment on the queen’s private engagements.”

Graham Smith from the anti-monarchy campaign group Republic told Declassified the queen was putting horses ahead of human rights. “Her love of horses should be very much secondary to her representing the values of this country,” he said. “She’s not obliged to spend any time with these people and she shouldn’t be doing so.”

He added: “There’s a very clear message being sent by her doing that, which is ultimately the British state is okay with them carrying on in power and that they will always be a friend to the British monarch. And that’s not the sort of message I think most British people would want to send to people who are ultimately dictators and despots.”

‘Highest dignitaries’

The queen’s love of horses has seen her foster close ties with several other controversial Gulf monarchs. She visited Oman’s Sultan Qaboos shortly before the Arab Spring in November 2010 as part of her trip to the UAE, charging the public £364,000 for their flights. Foreign Secretary William Hague accompanied her.

In Oman, Qaboos presented the Queen with a gold Fabergé-style egg and put on a cavalry display involving 700 horses. In return, she honoured him with a Royal Victorian Chain, an award “conferred only upon the highest dignitaries”.

Three months later, in February 2011, Qaboos and his regional counterparts would face unprecedented threats to their power, as activists staged sit-ins and protests against decades of misrule. Some were killed. Many more were arrested in Oman and across the Middle East.

The crackdowns did not seem to put off the British monarchy. Around 10 days after Qaboos’ security force shot protesters dead, the queen’s youngest son Prince Edward stopped off in Oman to meet the deputy prime minister and greet British military forces stationed in the country.

The following year, half a dozen Gulf monarchs visited London to mark Queen Elizabeth’s Diamond Jubilee, a celebration of her six decades on the throne.

The assembled sovereigns, joined by regents from other corners of the world, feasted on lamb, asparagus and wild mushrooms, courtesy of the British taxpayer.

Princes William and Harry, along with other Windsors, also participated in the red carpet affair, which saw the queen laughing and joking with Bahrain’s autocratic King Hamad.

Campaign group Republic criticised Hamad’s attendance at the Diamond Jubilee banquet, saying: “Thanks to the queen’s misjudgment, her jubilee will forever be associated with some of the most repressive regimes in the world.”

More than 40 protesters had been killed during Bahrain’s Arab Spring protests the previous year. Leaders of the country’s pro-democracy movement were sentenced to life imprisonment.

Even doctors were not safe. A hospital treating injured demonstrators was raided by police and scores of medics sent to prison by military courts.

An official commission, appointed by King Hamad, found hundreds of Bahraini activists were allegedly tortured.

Oman’s Sultan Qaboos did not attend the banquet in May 2012, but made up for it by sending 110 horses to a pageant at Windsor Castle that accompanied the Diamond Jubilee celebrations.

When one of his subjects, the activist Khalfan al-Badwawi, protested at the cost of transporting so many live animals to Britain by air, he was arrested and tortured.

Meanwhile, the Sultan made his own way to Buckingham Palace for a more private post-Jubilee lunch in June 2012.

Qaboos was accompanied by his veteran British adviser Sir Erik Bennett, who the queen had previously decorated. They were joined for the meal by UK foreign secretary William Hague.

Buckingham Palace declined to comment when asked by Declassified if it was ethical for the queen to meet Qaboos while one of his subjects was being tortured for protesting against his friendship with her.

‘Sportswashing’

After the Diamond Jubilee pageant at Windsor in 2012, Queen Elizabeth regularly appeared at the annual Royal Windsor Horse Show, sometimes sitting in the same box as Bahrain’s King Hamad, himself a horse racing enthusiast.

His entourage at Windsor often includes his son Nasser bin Hamad al-Khalifa, who is accused of involvement in the torture of activists during the Arab Spring and commands a military unit fighting in Yemen.

Nasser is married to a daughter of the controversial ruler of Dubai and regularly competes at the Windsor horse show.

The presence of Bahrain’s ruling family at the event has made it a target for protests by exiles, including one in 2013 by torture survivor Sayed Ahmed Alwadaei.

Alwadaei says his Bahraini citizenship was revoked in retaliation for protesting at the horse show.

He staged another demonstration at Windsor in 2017, when foreign minister Alan Duncan and former PM David Cameron were also pictured with King Hamad.

In response to that protest, Alwadaei’s sister was summoned to a police station in Bahrain for interrogation. Relatives of other activists involved in the protest were also taken into custody.

Jason Parkinson, a British photojournalist who covered their protest, was followed after the event by plainclothes Bahraini intelligence officers, who are alleged to have threatened him on UK soil.

In 2018, Alwadaei’s organisation, the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), filed a formal complaint against the horse show’s organisers, accusing them of “sportswashing” the Gulf regime’s human rights record.

Buckingham Palace refused to comment when asked by Declassified whether the queen’s friendship with King Hamad is appropriate.

A Foreign Office spokesman told Declassified: “Official royal visits are undertaken by members of the royal family at the request of the government to support British interests around the globe.”

This is Part 4 of our investigation into the British royals. Read Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 here.