- Foreign Office made the admission after losing a Freedom of Information court case to Declassified UK.

- Revelation strengthens Labour Party’s call for an independent inquiry of SAS role in the deadly raid on Sikh holy site.

- It comes as the High Court releases SAS emails showing concerns the elite unit committed a “massacre” in Afghanistan in 2011, raising questions about the role of British special forces across South Asia.

When hundreds of Sikh pilgrims were killed in June 1984 during the Indian army’s Operation Blue Star raid on the Golden Temple in Amritsar, thousands of Sikhs in Britain protested against the bloodshed at their faith’s holiest site.

So there was widespread shock when, 30 years later, I found newly released UK government papers showing Margaret Thatcher had sent a British Special Air Service (SAS) officer to Amritsar months before Operation Blue Star to advise on evicting Sikh separatists who had been occupying the Golden Temple.

My revelations in January 2014 led the UK’s then prime minister David Cameron to order an internal investigation by his top civil servant, Sir Jeremy Heywood, into the extent of the UK’s role in the massacre.

Heywood quickly assembled a team from Whitehall’s Cabinet Office – which supports the Prime Minister – to look into the affair. Three weeks later, the Heywood Review was published and concluded the advice given by the SAS officer had “limited impact in practice”.

Some Sikh activists branded Heywood’s review a “whitewash”, and the opposition Labour Party called for an independent review.

Heywood claimed his review was robust, with his team having “searched around 200 files (in excess of 23,000 documents) held by all relevant Departments covering the handling of events in Amritsar”.

As a journalist who often uses declassified government files for research, I was surprised that so many files were read in such a short period of time.

My surprise turned to suspicion after I asked the Cabinet Office how many staff hours were spent on the Heywood Review, and its cost. I was told that this information was not held by the government.

The National Guard memo

After a long delay the Cabinet Office sent me a list of the files Heywood’s review had examined. Some of these papers had already been released to the National Archives, where I had begun to inspect them.

These included a Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) file entitled “UK military training assistance to India”. Heywood’s team had seen the file, but not mentioned a key aspect of it in their review.

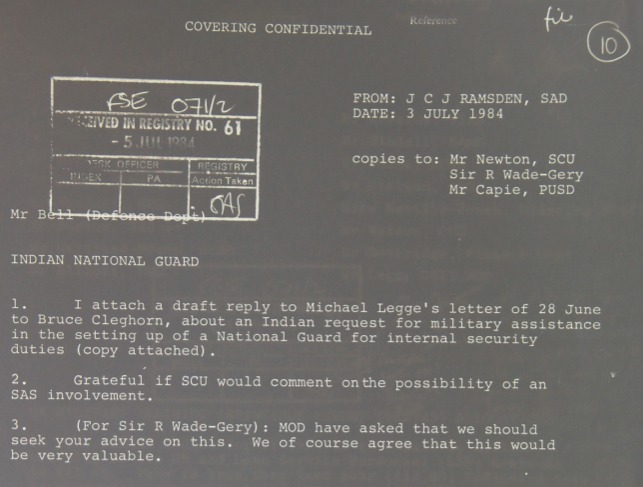

Part of the file discussed “an Indian request for military assistance in the setting up of a National Guard for internal security duties”. It was dated 3 July 1984, less than a month after the massacre.

Crucially, the memo shows British officials were considering “the possibility of an SAS involvement” in helping to set up the new unit.

The rest of the file containing this memo was censored, so it was unclear whether or not the SAS training had gone ahead.

After I viewed the National Guard memo, the Foreign Office temporarily withdrew it from the National Archives.

This episode piqued my curiosity, and I discussed the secrecy I was encountering with the former Liberal Democrat leader and Special Boat Service (SBS) veteran Paddy Ashdown, before his death in 2018.

“There ought to be much more transparency over historical operations,” Ashdown told me, saying he was struggling to access records about missions he had undertaken while in the SBS during the 1960s.

“Our special forces are being ludicrously overprotected on records that are, never mind 30 years old, but 70 years old,” he opined.

Britain’s special forces are not required to release any of their historical files to the National Archives, nor are they subject to the Freedom of Information Act— or any parliamentary scrutiny.

The Cleghorn connection

As my investigation went on, I noticed in the National Archives database that the Foreign Office had an entire file from 1984 titled “Indian National Security Guard”.

The file was also not accessible to the public, nor did it appear on the list of files that Heywood’s team had examined.

The Indian National Security Guard, which sounds strikingly similar to the nascent National Guard mentioned in the mysterious memo, was set up after the Golden Temple massacre.

It was “modelled” on the SAS and became an elite commando unit – nicknamed the Black Cats – which was involved in further raids on the Golden Temple and Sikh separatists.

Rather than the SAS mission to Amritsar being “limited” as Heywood claimed, was it in fact the start of a pattern in which British special forces repeatedly aided India’s crackdown on Sikhs? And why had Heywood not been shown this file?

Among the British diplomats named in the UK government’s first “National Guard” memo from July 1984 – the month after Operation Blue Star – was a member of the Foreign Office’s South Asian Department, Bruce Cleghorn, who was privy to the discussions about possible training for the elite unit.

I later discovered that Cleghorn had gone on to work as a “sensitivity reviewer” for the Foreign Office during 2014. In this role, he was tasked with vetting files before they were released to the National Archives to ensure any embarrassing information was not disclosed.

According to the declassified files, the day before Operation Blue Star, Cleghorn had warned colleagues: “It would be dangerous if HMG [the British government] were to become identified, in the minds of Sikhs in the UK, with some more determined action by the Indian government, in particular any attempt to storm the Golden Temple at Amritsar.”

The potential significance of Cleghorn’s views became apparent in September 2017 when a press officer at the Foreign Office admitted to me that its “sensitivity reviewers helped to locate and identify FCO papers” for the Heywood Review.

This raised the possibility that diplomats-turned-censors such as Cleghorn – who were at the heart of UK-India relations during Operation Blue Star – had been allowed to influence which records the Heywood Review saw.

I became increasingly concerned about a cover-up when the FCO’s press office refused to confirm whether Cleghorn was among the sensitivity reviewers who helped find files for Heywood.

Court battle

Two-and-a-half years of obstruction followed as the Foreign Office refused to answer a freedom of information (FOI) request about this issue. Whitehall claimed Cleghorn would be subjected to online trolling and even physical attacks from the Sikh community if his role in the Heywood review was confirmed.

I took the government to an Information Tribunal to demand disclosure. Tanmanjeet Singh Dhesi, a Labour MP for Slough – a seat in West London with a large Sikh population – gave a witness statement in support of my case. He argued the Foreign Office’s concerns about reprisals from the Sikh community were “thinly concealed racism”.

Dhesi stressed that British officials active in Anglo-Asian affairs in the 1980s should not then have been permitted to “select which files investigators had access to” in 2014.

He added that if that did prove to be the case, it would not result in criticism of the individuals involved, but rather a call for a truly independent inquiry “to rectify the apparent inadequacy of the Heywood Review”.

Meanwhile, Graham Hands, the senior sensitivity reviewer at the Foreign Office, gave a witness statement on behalf of the government for the court case. He confirmed that sensitivity reviewers had assisted the Heywood Review with looking for “potentially relevant papers on FCO files” that “could be drawn to the attention of the Cabinet Office”.

As a result of this process, he said a “large number of files were identified and examined”, checked by the Foreign Office’s South Asian Department, “before being drawn to the attention of the Cabinet Office”.

Whilst Hands claimed my concerns about potential conflicts of interest were “overstated”, his witness statement served to confirm the significant role played by sensitivity reviewers in the Heywood Review.

Despite the British government’s best efforts, this year the Information Tribunal found partly in my favour, concluding that “there should be transparency of all relevant issues about a matter such as the Heywood Review”.

While the judge stopped short of ruling that Bruce Cleghorn’s own role should be revealed, as it might cause him “distress”, the Tribunal did order the Foreign Office to answer my more general question.

This was whether any Foreign Office officials “who were involved in UK-India affairs in 1984 helped locate and identify FCO papers in 2014 for Sir Jeremy Heywood’s review into allegations of UK involvement in the Indian Army’s operation Bluestar”.

In June 2020, the FCO finally answered this question, conceding: “We can confirm that one or more officials who worked on UK/India diplomatic relations in 1984 helped locate and identify papers for this 2014 review.”

Tanmanjeet Singh Dhesi MP welcomed the ruling, telling Declassified: “This judgment vindicates the stance taken by the likes of myself and strengthens the Labour Party’s call for an independent inquiry to establish the extent of the Thatcher Government’s involvement in the 1984 attack on the Darbar Sahib (Golden Temple) complex in Amritsar.”