Declassified UK can reveal that Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), Britain’s largest intelligence agency, has gained access to at least 22,000 primary and secondary school children in dozens of UK schools, and that the organisation may be spying on children.

GCHQ officers are operating in at least one school, while parents of pupils at schools across the programme do not appear to have been informed about the extent of the spy agency’s role in it.

Evidence also suggests that quotes purporting to be from children praising the programme have been manufactured.

Further, GCHQ’s Cyber Schools Hub (CSH) programme, also known as CyberFirst, appears to be disseminating propaganda to school children, telling them it acts as the “heart of the nation’s security”. This is controversial, given that GCHQ’s programmes of mass surveillance have been found to be unlawful by the European Court of Human Rights and that the agency also conducts offensive cyber operations.

The stated purpose of the CSH programme is to enable secondary school children aged 11 to 17 years old near GCHQ’s base in Cheltenham to “experience new ways of learning in an innovative cyber environment”. It also aims to recruit children for jobs in the sector by helping to “educate on the opportunities that exist within the cyber security and computing industry”.

However, Declassified can reveal that the programme — which has been running since 2018 — has expanded into primary schools, where students range from 4 to 11 years old. While programme literature admits that the project includes 23 schools, Declassified has found that nearly double this number are involved, including more than 10 primary schools.

Declassified has also seen evidence that a “code club” set up at one primary school is staffed entirely by officers from GCHQ. The intelligence agency has also tried to gain access to school children by providing much-needed technology to local libraries, while its “recruitment teams” have been mobilised to deal with enquiries from schools involved in the programme, according to documents seen by Declassified.

There are suspicions that GCHQ’s programme is being used to spy on children. Declassified has seen evidence that GCHQ and local police launched a “joint tag team event” at one school to gain access to a pupil who had been reported to the authorities by his school for being “very talented”, such that “teachers were worried [he] may be about to cross the line with his online cyber activities”.

There is no evidence the child had done anything wrong to become a target of GCHQ, or that they or their classmates were made aware they were participating in an event under false pretences.

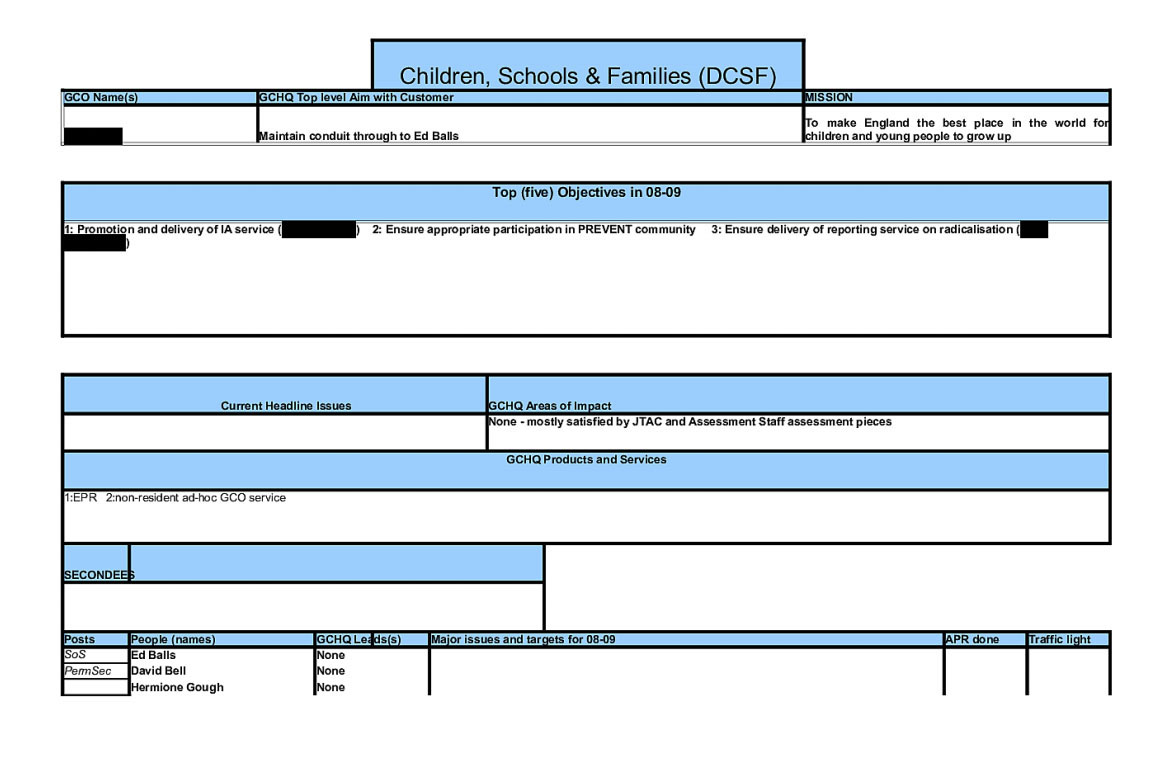

The exposures by US whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed that one of GCHQ’s “top objectives” in the recent past was the “delivery of a reporting service on radicalisation” for the UK Department for Children, Schools and Families (now Department for Education), assumed to be targeted at children in schools. It is unclear if the CSH programme is part of this “reporting service”.

An internal GCHQ slide leaked by whistleblower Edward Snowden which shows the agency’s aim to “ensure delivery of reporting service on radicalisation” to the UK government’s Department of Children, Schools and Families.

GCHQ runs the CSH programme through one of its arms, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), which opened in 2016. GCHQ says it employs almost 6,000 people in Cheltenham and at some smaller bases around the UK, although the agency has in recent years secretly expanded its workforce, reportedly employing thousands more staff.

The majority share of the £2.48-billion budget for Britain’s intelligence services is taken by GCHQ, which has twice the number of personnel of the other major security services, MI5 and MI6, combined.

Both GCHQ and the schools themselves cite national security exemptions to block requests for information about the cyber schools programme, but Declassified has seen newsletters produced for a short period from December 2018 to July 2019 which outline some activities.

“GCHQ is an employer that requires a certain skill set—and perhaps a certain mind-set,” Jen Persson, director of Defend Digital Me, an organisation set up to defend children’s right to privacy, told Declassified.

“Recruitment in that sector is not about a single event, but a drip-feed developed over time. Children are vulnerable as they develop into adulthood, and there is regulation in other areas, to protect them from undue adult influence, like online advertising – yet it sounds like spies can walk into schools whenever they want with no transparency or independent oversight.”

Unlawful surveillance

A downloadable lesson plan in the CSH programme, which includes the tag “Year 7” – i.e. 11-12 year olds – has a slide which instructs the children: “GCHQ has been at the heart of the nation’s security for 100 years. It has saved countless lives, given Britain an edge, and solved or harnessed some of the world’s hardest technology challenges.”

The slide is an unattributed quote from GCHQ director Jeremy Fleming. It is not known if parents are aware that such lessons are disseminating propaganda about GCHQ’s history.

Files revealed by Edward Snowden in 2013 show that GCHQ had been secretly intercepting, processing and storing data concerning millions of people’s private communications, including people of no intelligence interest – in a programme named Tempora.

In 2018, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that UK laws enabling such mass surveillance were unlawful, violating rights to privacy and freedom of expression. GCHQ has also operated offensive cyber operations against countries such as Argentina and plays a key role in UK military interventions overseas.

On top of this, GCHQ has a secret cyber warfare unit, named the Joint Threat Research Intelligence Group (JTRIG), which takes 5% of the organisation’s budget. Its stated purpose is to “destroy, deny, degrade, disrupt” enemies by “discrediting” them, and its operations include “honey traps”, “false flags” (posing as an enemy), or “writing a blog purporting to be one of their victims”.

According to Richard J Aldrich, a professor at Warwick University and author of the authoritative history of GCHQ, “One of the enemies on JTRIG’s list are investigative journalists who pose a ‘potential threat to security.’”

It appears parents are not being made aware of the full gamut of GCHQ’s activities – or the extent of its role in the CSH programme. When Declassified asked the NCSC what information is given to parents about the programme, the agency replied: “We have no contact with parents. What teachers/schools share with parents is done independently of NCSC.”

Slides from a downloadable lesson plan made available by GCHQ’s schools programme. (Photo: Cyber Schools Hub)

The CSH programme has already reached over 22,000 children in its pilot phase in schools in Gloucestershire, southwest England, but the British government plans to expand the programme across the whole country.

The NCSC recently announced that because “the CSH pilot has proved to be successful at a local level” it now “wishes to increase the scale of ambition and formally recognise schools” in a new CyberFirst schools programme, which will include schools in Wales. The NCSC team is already covering expenses to enable teachers from around the country to attend CSH events in Gloucestershire, according to documents seen by Declassified.

Only two questions have been asked in Britain’s parliament about the CSH programme, and its total cost – paid for by the UK taxpayer – is classified. The NCSC told Declassified that the agency “wouldn’t offer comment on finance specifics”.

Primary schools

GCHQ recently boasted, “we visit local primary schools to teach children about the history of coding and maybe even inspire the next generation”. These programmes are not public.

GCHQ quotes primary school children apparently praising the intelligence agency’s educational outreach. “I think it’s the best thing EVER”, one child apparently said. “The lesson was fabulous”, another was purported to say.

All secondary schools in Gloucestershire were invited to tender to be a hub for the CSH programme in October 2017. But, according to documents seen by Declassified, by the end of 2018 the NCSC had “started a focused primary school trial” by using CSH schools to run after-hours clubs in “feeder” schools for 4-11-year-olds.

Schools supported include the Kings, Linden and Abbeymead primary schools, all in the vicinity of GCHQ’s Cheltenham headquarters. The computer science teacher at another nearby school, Denmark Road, provided a further three “exciting and stimulating” computer science outreach sessions at Kingsholm, another local primary school.

The CSH website states that primary school teachers can collect “teacher crates” from the NCSC which can be used to “develop lesson and activity plans”. The programme has a list of courses – some devised by private sector partners – specifically aimed at primary school children, including playing the game Minecraft while learning the Python computer coding software.

In Spring 2019, St James primary school in Gloucester launched a “code club” for its pupils. The club, the newsletter notes, is “staffed entirely by software engineers from GCHQ, which allows the club to be offered for free”. The club was scheduled to run until the end of the school year with “lots of new topics”.

The NCSC told Declassified: “Secondary teachers involved in the initiative expressed the need to develop interest in computing at primary school level. We supported primary schools in delivering stimulating Cyber Schools lessons.”

An entry in the March/April 2019 newsletter, produced by GCHQ, which outlines its officers entry into one primary school to set up a “code club”.

Spying on children?

Declassified has seen evidence that GCHQ’s project is closely supported by the police’s regional cyber crime unit, with police officers involved in the programme entering schools to provide “fun sessions around ethics… and the Computer Misuse Act”.

The NCSC notes: “On several occasions this has been done as a tag team with NCSC providing insight into the role of both GCHQ and NCSC, and the associated career opportunities if students stay on the right side of the law.”

On one occasion, the West Midlands police cyber crime unit was called in to a school in Hereford, which is not mentioned as being part of the CSH programme, because there was a “very talented student that the teachers were worried may be about to cross the line with his online cyber activities”. The child had expressed interest in working for GCHQ.

The NCSC team suggested a “joint tag team event” with the police, where they would “emulate the sessions” they had previously run with the police. The school acceded and a session was run for a morning with the individual and his classmates. “Hopefully a clear and correct pathway [was] highlighted to the talented student,” notes the newsletter. It is unclear if the student was at a primary or secondary school.

Despite putting on the event, the NCSC told Declassified: “We don’t have any information on this”.

An entry in the June 2019 newsletter, produced by GCHQ, which outlines the activities in its schools programme, suggesting it is being used to spy on children.

One newsletter notes another event for girls held at a school close to GCHQ headquarters and includes Ella and Chloe in Year 8 (i.e. 12-13 years old) together proffering the quote: “Diversity in perspectives, leadership and experience is good for Cyber. The wider variety of people and experience we have defending our systems, the better chances of keep [sic] the UK safe”.

But this quote may not be genuine since, aside from sounding more like language used by GCHQ media relations than a Year 8 pupil, the same quote is attributed to a different 13-year-old pupil – “Evie” – on another CSH blog post.

The NCSC told Declassified: “Teachers provide the quotes from students.”

A suspicious quote praising GCHQ’s schools programme, which in the first CSH blog post is attributed to 13-year-old pupil “Evie” and in the CSH newsletter below is attributed to two different pupils: “Ella and Chloe in Year 8”.

A visit to the schools

Before the coronavirus crisis hit the UK, I took a 25-minute drive west from GCHQ’s headquarters in Cheltenham to Newent Community School. Driving through lush countryside and quaint villages, it felt far away from the world of high-stakes surveillance by the time I arrived in Newent, a village of around 5,000 people.

But Newent School is at the centre of attempts by GCHQ to cultivate the next generation of cyber-competent spies and expand into Britain’s educational system. The school is one of just two “hub schools” which are the centrepiece of the CSH programme.

My email and phone requests for interviews to Newent and its sister hub, Cleeve School, were initially answered, but then ignored.

When I arrived unannounced in person, the Newent principal Alan Johnson acceded to speaking to me. Initially, he said he would give me an interview on the record, but then said he would only speak on background.

He could tell me nothing tangible that being a “hub school” has done, saying it has brought no investment or new facilities. The programme, he said, has simply made the school focus more on “cyber security”.

A CSH newsletter, however, outlines that the NCSC team funded two companies to run sessions for 50 11-year-olds on “e-textiles” at Newent School. “The school is now looking to run a regular wearable tech focused lunchtime club,” the newsletter continued.

Johnson pointed to a shelf in his office which has toys for toddlers and explained that all of them are potential surveillance devices. This is the big lesson he wants his pupils to imbibe, he told me.

Johnson took me on a tour of the school and judging by the peeling paint and sparse facilities, the reason for his contention that he will take investment from anywhere he can get it became obvious.

Shelves full of electronic toys in the office of Alan Johnson, the principal of Newent Community School, which Johnson uses to demonstrate the dangers of surveillance to the children in his school. (Photo: Matt Kennard)

National security schools

Cleeve School, which is the lead hub school in the GCHQ programme, and located just a 10 minute drive from its headquarters, provides a different picture. From the outside it looks state-of-the-art architecturally, and as you walk to reception, well-equipped computer rooms run along the side of the building.

The receptionist initially looked proud when I asked if it is a cyber “hub school” and said she would go to get some information and ask about an interview.

She returned after speaking to someone on the phone for a couple of minutes. She said there was no information on the programme she could give me and the person who runs it was in a meeting and wouldn’t be out until the end of the school day. When I returned I was told he was still not available.

I requested basic information about what the GCHQ programme is promoting at Cleeve using the Freedom of Information Act provisions, but the IT teacher running the programme, Martin Peake, wrote back, stating “that the information requested is exempt under section 23(1) of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 which relates to information supplied by, or relating to, bodies dealing with security matters.”

He added that this is “an absolute exemption and does not, therefore require the application of the public interest test in favour of disclosure”.

Jen Persson, director of Defend Digital Me, told Declassified: “If I were a parent at a school that cited a national security ‘exemption’ to a question about what GCHQ is promoting to my child, I’d be on the phone to the governors to find out why, and want a very thorough and public explanation of their purposes. I’d ask, is my child being groomed?”

Peake joined Cleeve as head of computer science in September 2017, the month before the tenders to NCSC were submitted. He says he is “currently working with NCSC to develop the Cyber Schools Hub”.

Peake has a history working in the arms industry, from 1988-1994 as a software developer for “defence communications projects in the air defence sector” where he “successfully bid for new contracts in the UK and France”. Before that he had been a software engineer on the head-up displays for the military jet fighters Sea Harrier and Tornado.

Email and telephone requests to the NCSC have yielded next to no further information about the CSH programme. Declassified tried both press numbers on the agency’s website and neither worked. An email was eventually answered and a request for a school visit and an interview with someone running the programme was put in.

Despite saying that a visit could be arranged, nothing was heard for several months, and requests for updates were not forthcoming. No interview with any administrator at the NCSC was granted.

Royal approval

One thing that has been publicised is that students from Newent and Cleeve were invited to the main GCHQ building in Cheltenham to “help GCHQ celebrate its centenary year” along with Prince Charles.

The newsletter noted that Prince Charles “went to great lengths to show how impressed he was with the NCSC running such a project, with the teachers and students involved”. “The project teachers and students were thrilled to be given such a fantastic opportunity and to talk to HRH about the impact the project has had on them and their schools,” the newsletter added.

In March 2019, Years 7 and 8 students from Newent also visited the NCSC offices in London as the guests of its deputy director for defence and national security. The newsletter reported that the pupils returned to school “buzzing”. “They loved the opportunity to visit the NCSC offices in London,” it noted, adding the students were left “thrilled and enthralled” by seeing what the NCSC does.

In 2019 the CSH project supported students at another school, Wyedean to attend the Cheltenham Science Festival where GCHQ sponsored the Cyber Zone area. Students were so engaged with the activities, the NCSC claimed, “that they nearly forgot to get on the bus back to school at the end of the day”.

Prince Charles meets staff and students from Newent and Wyedean, two schools involved in the Cyber Schools Hub programme, at the headquarters of GCHQ in Cheltenham, 13 July 2019. (Photo: GCHQ)

GCHQ’s public relations

The plethora of programmes GCHQ has initiated in recent years is intended to create the next generation of cyber-competent spies. The secret intelligence service, MI6 also recently revealed it has cut its age of enlistment to 18 to attract more technologically savvy officers.

GCHQ has been keen to mend its reputation after the Snowden revelations and is targeting young children in several ways. Blue Peter, the flagship children’s show on BBC, ran a competition last year “giving three lucky viewers” the chance to visit the GCHQ headquarters in Cheltenham. The BBC added, “To be in for a chance at winning this incredible prize, you must create a simple code to spell ‘Enigma’ and hide it within a poster you’ve designed to mark GCHQ’s 100th anniversary.”

In 2017, GCHQ created the CyberFirst girls competition for children aged 12-13 years old with the stated aim of increasing female participation in the cyber sector. By 2020, 520 schools across Britain had signed up to participate.

Alex Chalk, the Conservative MP for Cheltenham, has been a supporter of GCHQ moving into Gloucestershire’s schools. “The thing that struck me was that we had an asset in GCHQ, which was absorbing a growing amount of public money, billions of pounds, and yet its impact… was quite limited,” he told me last year.

“I read around the subject and saw what the Israelis had done in a place called Beer Sheva in Israel, where they’ve got their equivalent of GCHQ, and their equivalent of Cambridge University, which is called Ben Gurion University.”

In May 2018 – as GCHQ’s schools programme was being launched – Conservative Friends of Israel and the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs donated £1,800 to Chalk to cover a trip to Israel to see the CyberSpark Cyber Innovation Centre in Beer Sheva.

The British government has another project, Cyber Discovery, which costs £20-million and aims to provide “free online, extracurricular” cyber activities to children as young as five years old.

This project is adapting to the coronavirus crisis. Last month the government set up an online “cyber security school” aimed at “thousands of young people”.

“At a time when schools remain closed to most children, the online initiative aims to inspire future talent to work in the cyber security sector,” the government stated.