- UK appears to be the sole government funder of the new Coalición Anticorrupción

- Group was established last year by transparency organisation linked to key opposition figures, some supporters of the 2002 attempted coup against President Chávez

- The coalition’s coordinator has said Venezuelans ‘must continue the fight in the streets’ against the Maduro government

- Group’s partners include the ‘Thatcher Centre’, whose website was registered days before the new coalition

- UK ambassador to Venezuela – who was in place when project began – has been named as a ‘strictly protect’ US informant

- British embassy in Caracas briefed ‘every three months’ on the coalition’s progress, Declassified told

- UK Foreign Office and British embassy in Caracas stonewall Declassified’s questions about individuals involved in coalition

The UK government has given £450,000 to “Transparencia Venezuela”– a local branch of the international non-governmental organisation Transparency International – to set up a coalition headed by an outspoken opponent of the government of Nicolás Maduro, Declassified can reveal.

In information released to Declassified, the UK Foreign Office stated that it awarded £250,000 in 2019 to establish the “Coalición Anticorrupción”, which it describes as “an anti-corruption coalition of civil society and free media actors, to help them tackle corruption and organised crime in Venezuela”.

The Foreign Office disbursed a further £200,000 to Transparencia Venezuela for the period from March to December 2020 “to strengthen the sustainability of the coalition”.

Declassified has found that the coalition is run by – and partners with – some of the country’s most outspoken individuals and groups opposed to Maduro’s leftist government. The UK and US governments recognise opposition figure Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s “interim president” and have openly sought to remove Maduro from office.

The coalition, whose sole external funder appears to be the British government, already includes 781 organisations and promotes 243 “initiatives”. Transparencia Venezuela calls the new group a “citizens’ movement” which hopes to achieve a “real transformation” and a “new Venezuela”.

Transparencia Venezuela told Declassified that they “present progress and project management reports every three months” to the UK embassy in Venezuela’s capital, Caracas.

The funds were awarded by the UK’s £1.26-billion Conflict, Stability and Security Fund (CSSF), which, according to the government, “works to build peace and stability in countries at risk of instability”.

The UK government previously refused Declassified’s requests to detail who it is funding in Venezuela. In response to two recent Freedom of Information requests, the UK Department for International Development (DFID) said it was “withholding details of those organisations we are supporting inside Venezuela” on health and safety grounds. It is not clear what relevance health and safety has to the requests.

The UK government has not openly publicised its funding for the coalition, which has been added to an existing CSSF programme titled “Peru/Colombia Serious Organised Crime”.

A programme summary for this project, dated March 2020, is the government’s only public reference to the Venezuelan coalition that Declassified could find. It states that £0.3-million in aid money was allocated in 2019-20 for a “Venezuela anti-corruption project”.

The document adds that “the programme is also for the first time funding activity in both Panama and Venezuela” and that the CSSF anticipates “increased activity” in both countries with the Venezuelan project “focusing on civil society’s resilience to corrupt State practices”.

The funding raises questions about the government’s commitment to transparency since the project does not appear to be mentioned on the government’s “DevTracker” website, which is meant to list all the UK’s international aid projects.

A spokesperson for Transparencia Venezuela told Declassified the group “focuses on transparency and the fight against corruption, and for this reason it monitors the resources that are managed or are under the responsibility of the current State organs”.

‘Fight in the streets’

On its “about us” page, the coalition writes that its motivation is to “actively fight to put an end to the deep-seated structural problems in this country that have endured for almost two decades”.

Many of its national initiatives target the Venezuelan government, while its news page hosts extensive criticism of Maduro’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic and corruption allegations.

The group’s website does not specify who runs the coalition and the Foreign Office and British embassy in Caracas ignored Declassified’s questions about the individuals involved in the coalition.

However, a recent briefing lists Yonaide Sánchez as its national coordinator. Sánchez, a professor at Lisandro Alvarado University in Barquisimeto, northern Venezuela, is a supporter of Guaidó and has been outspoken in backing opposition efforts to remove the Maduro government.

During violent street protests in April and May 2017, Sánchez wrote that “each announcement by Maduro confirms that we must continue the fight in the streets. The government is more and more isolated.”

In January 2019, shortly after Guaidó had proclaimed himself Venezuelan president, Sánchez wrote: “I, Yonaide Sánchez… only recognise Juan Guaidó – president of the National Assembly – as the legitimate president of Venezuela. I hope for the good of my country that my union agrees.”

Sanchez has also urged “international aid” to be delivered to Venezuela in order to “combat corruption”, and announced that “history will not absolve” Maduro.

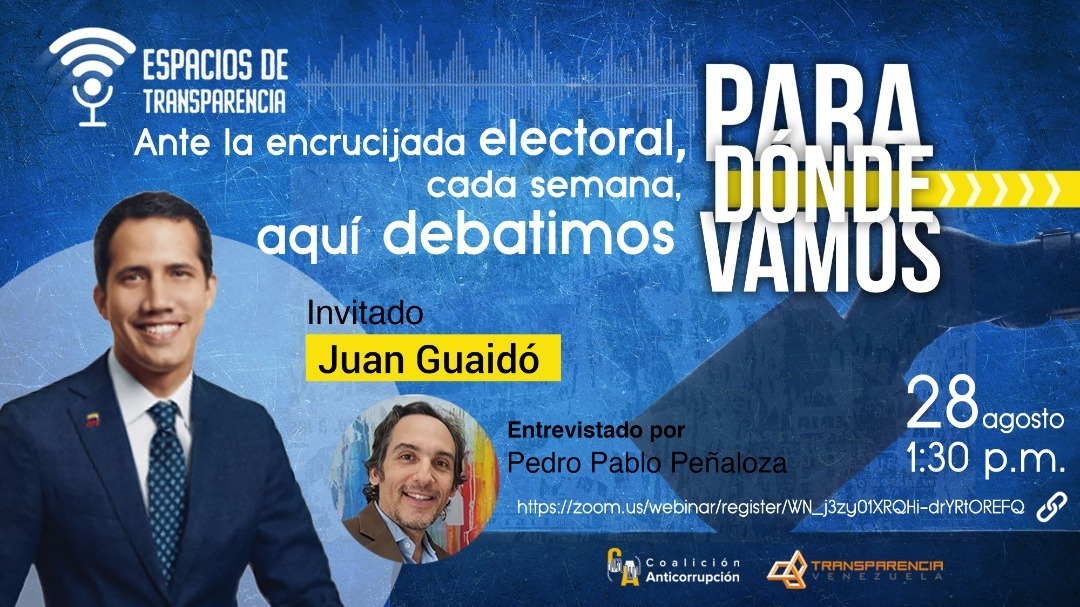

In August 2020, the coalition invited Guaidó for a discussion about the “electoral crossroads” in Venezuela, asking, “Where do we go from here?” Introducing Guaidó as the “interim president” of Venezuela, the conversation considered the benefits of inviting the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) back into Venezuela after it was expelled by then president Hugo Chávez in 2005 over allegations of espionage.

British funding of “anti-corruption” activity in Venezuela is likely to add to suspicions that the UK is empowering civil society organisations as a means to remove the Maduro government. The British government is not known to fund anti-corruption groups in allied states, such as the Gulf regimes, where corruption is routine.

In February 2017, the then UK ambassador to Venezuela, John Saville, participated in an event on “transparency” alongside Guaidó. This May, Saville was revealed as head of the Foreign Office’s Venezuela Reconstruction Unit, which the Venezuelan government claims operated in secrecy. The unit ostensibly seeks to “lead Venezuela towards a peaceful and democratic resolution” to its ongoing political crisis.

At a coalition event in March, Duncan Hill, the deputy UK ambassador to Venezuela, reportedly said: “Venezuela has been the victim of the greatest looting in history.”

The current UK ambassador in Caracas, Andrew Soper, served as the First Secretary in Washington DC from 1995-1999, and was exposed as a “strictly protect” US informant in a January 2010 US diplomatic cable while he was British ambassador to Mozambique.

As the coalition was being constructed in October 2019, Soper reiterated that “Guaidó has the friendship and support of the United Kingdom”.

The Foreign Office did not reply to Declassified’s query about the status of Soper’s current relationship with the US embassy in Caracas.

The Thatcher Centre

Of the 20 national organisations incorporated into Venezuela’s anti-corruption coalition, many are long-standing critics of the government and past or current recipients of Western government funding.

One member is the “Thatcher Centre”, whose website was registered within a week of the coalition’s own website. Though the registration information has been made private, both proxy registrations were made by the same company based in Arizona, US.

The Thatcher Centre was founded in August 2019 by Venezuelan journalist Guzman González and is based in the northern state of Carabobo. Named after the former British prime minister who was a strong supporter of right-wing regimes in Latin America, the centre says its goals are a “strong citizenry and a small state”.

Superatec AC, another member of the coalition, received an $80,000 grant from Citibank in 2019, while the head of another member – Fetrasalud, the federation of health workers – called on all sectors of the country to join Guaidó on national protests during March 2020.

The coalition also includes Asociación Civil Súmate (Civil Association Join Up), a longtime recipient of funds from the US government’s National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and which was founded and directed by key opposition figure Maria Corina Machado.

Corruption is a serious problem in Venezuela, and misuse of public funds has exacerbated an already severe economic crisis. Corruption ratings, however, are all produced by organisations directly or indirectly funded by Western governments seeking to remove the Maduro government.

In 2017, former chief prosecutor Luisa Ortega fled the country after being sacked and was given asylum in neighbouring Colombia. She alleged that Maduro is implicated in the corruption scandal around the Brazilian construction firm Odebrecht, and that a top Venezuelan court is blocking an investigation, although no evidence was provided publicly to support the claims.

Meanwhile, envoys of Guaidó have been accused of appropriating funds earmarked for Venezuelan military deserters who fled to Colombia in February and March 2019. According to Miami-based outlet PanAm Post, two Popular Will party officials inflated the count of the deserters in order to receive extra funds, and were consequently investigated by the Colombian government.

In response to the scandal, Guaidó solicited Transparencia Venezuela to launch an inquiry, which largely absolved those accused of embezzling funds. After publishing its findings, Guaidó’s team publicly thanked Transparencia Venezuela for its work, claiming the inquiry proved the Venezuelan opposition’s “commitment to transparency and proper use of resources”.

Transparencia Venezuela

Transparencia Venezuela claims to be a “non-partisan” actor in Venezuela although its co-founder and director, Mercedes de Freitas, has established and managed a number of US-funded institutions in the country.

De Freitas has been a director of Fundación Momento de la Gente (People’s Moment Foundation), a Caracas-based legal monitoring organisation which received significant funding from the NED and the National Democratic Institute (NDI), another “democracy promotion” foundation funded by the US government.

According to documents released by WikiLeaks, the NDI has funded Venezuelan opposition groups since the early years of Chávez’s presidency.

The NED was founded in 1983 under US President Ronald Reagan after a series of embarrassing scandals for the CIA, and has been described by the Washington Post as the “sugar daddy of overt [US] operations”. Allen Weinstein, who directed the research study that led to the creation of the NED, told the newspaper: “A lot of what we do today was done covertly 25 years ago by the CIA.”

Through institutions like the NED, the US government has disbursed money in Venezuela with the aim of effecting regime change for two decades. In 2011, the NED funded anti-Chávez rock bands in a bid to destabilise the government.

Documents obtained under the US Freedom of Information Act show that, in April 2002, De Freitas emailed the NED to show support for the unsuccessful coup attempt against Chávez. As The Nation reported, her email focused on “defending the military and [businessman and coup leader Pedro] Carmona, claiming the takeover was not a military coup”.

De Freitas has also worked as a coordinator of Queremos Elegir (We Want to Choose) – a civil society organisation which received US funding and was part of the movement against Chávez during the early 2000s.

Since 2010, De Freitas has also been vice-president of Fundación Tierra Viva (Living Earth Foundation), which promotes “the conservation of natural resources” but whose financial patrons include oil companies Chevron, Total Oil & Gas, Shell Venezuela, and the British Embassy.

Transparencia Venezuela’s financial audits, published yearly since 2005 (except for 2019 and 2020), show that the British embassy in Caracas has been among its key funders.

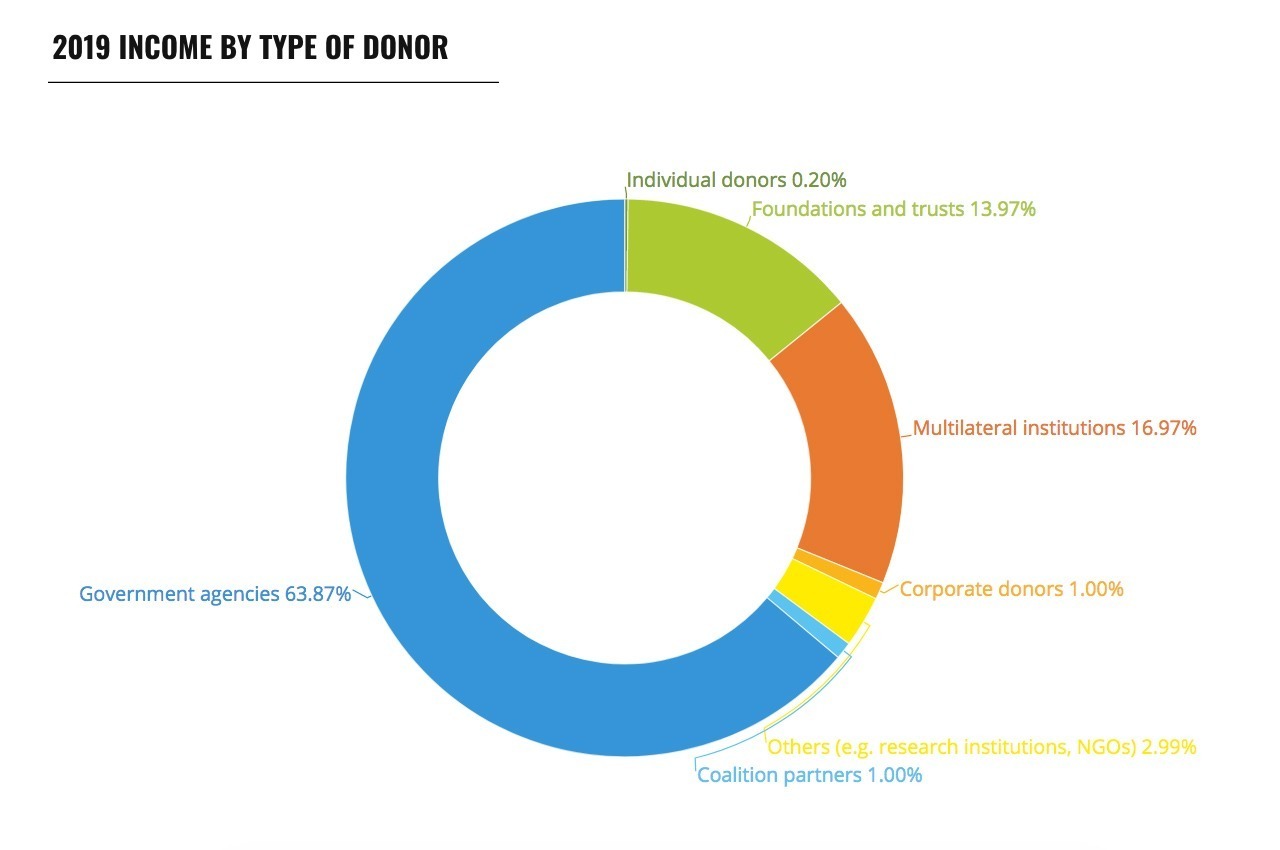

The Transparency International umbrella organisation, which is based in Berlin and has an operating income of £25.7-million, has been funded by the US and UK governments, among others, since its founding in 1993. In 2019, DFID was the largest government donor, giving €4.4-million, nearly double the next largest government backer, Canada’s Foreign Office. The US State Department gave €743,799.

Transparency International’s largest donor in terms of private foundations is Anglo-Australian mining giant BHP (formerly BHP Billiton), which gave the group €1.9-million in 2019. Other donors have included Shell and Exxon Mobil, which was engaged in a years-long battle with the Chávez government regarding oil nationalisation. Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

One of Transparencia Venezuela’s four corporate members, CEDICE, is a think-tank which “believes opening oil to private investment” in Venezuela “is a step in the right direction”. With support from the Atlas Network, a libertarian US think-tank that supports right-wing political movements across Latin America, CEDICE funded the “Citizen Oil” research project aimed at exploring the benefits of oil privatisation, which was later included in Guaidó’s economic plan for Venezuela.

Transparencia Venezuela told Declassified it is not calling for the removal of Maduro. “The coalition calls for transparency in management, with accountability, citizen participation and a justice system that ends impunity”, its spokesperson said. They added that the UK government was funding the coalition because it was anti-corruption, not anti-government.

Members of the opposition

On Transparencia Venezuela’s nine-member Board of Directors sits the former director of CEDICE, Rocío Guijarro, who was one of the first figures to sign the legislation in 2002 which dissolved Venezuela’s democratic institutions during the coup against Chávez.

Also on the board is Andrés Duarte, a member of the board of the Venezuelan Petroleum Chamber, whose goal is to increase private participation in the country’s oil sector. Miguel Bocco, one of Transparencia Venezuela’s founding members and also on its board, is a past director of the Venezuelan Petroleum Chamber, and has called for the privatisation of Venezuela’s oil sector.

Gustavo Linares Benzo, a lawyer who sits on Transparencia Venezuela’s Advisory Board, argued as early as November 2018 that Guaidó should apply Article 233 of the Venezuelan Constitution to claim the Venezuelan presidency.

Article 233 specifies that, with an “absolute vacuum of power” resulting from the “permanent physical or mental incapacity” of the president or “abandonment of post”, the president of the National Assembly legally assumes office. This argument provided the key legal justification for the attempted replacement of Maduro.

Transparencia Venezuela also lists 24 members including Carlos Fernández. As president of the Federation of Chambers of Industry and Commerce (Fedecamaras) in 2002, Fernández was a key figure in the three-month sabotage of Venezuela’s oil industry which aimed at toppling Chávez. Jorge Botti, another former president of Fedecamaras, is also listed as a member.

A spokesperson for Transparencia Venezuela told Declassified: “Our staff and allied organisations are human rights defenders, fighters for the right to health, to the wellbeing of children, to indigenous communities, to vulnerable groups, to access to information, to justice, amongst other things.” The spokesperson added: “In the Coalition we do not accept the participation of political parties or organisations with electoral political ends.”

The UK Foreign Office and the British embassy in Venezuela did not return Declassified’s requests for comment. The Coalición Anticorrupción had no staff or contact information on its website.