“This could grow into something awkward if pursued,” wrote the head of the Army Department in the Ministry of Defence in the margins of a letter in 1977. He could never have imagined those words would form part of a Supreme Court ruling decades later.

The “something awkward” was a bold statement that British ministers had authorised torture in Northern Ireland – torture being the one crime that is outlawed, without exception, in both domestic and international law.

The 1977 letter was from Labour home secretary Merlyn Rees to then prime minister Jim Callaghan. It stated that Conservative defence secretary Lord Peter Carrington had ordered the torture of 14 men, who had been taken at gunpoint from their homes in 1971 and held without trial in Northern Ireland.

Others with knowledge of the operation included home secretary Reginald Maudling, Northern Ireland minister Brian Faulkner, and defence minister Lord Balniel.

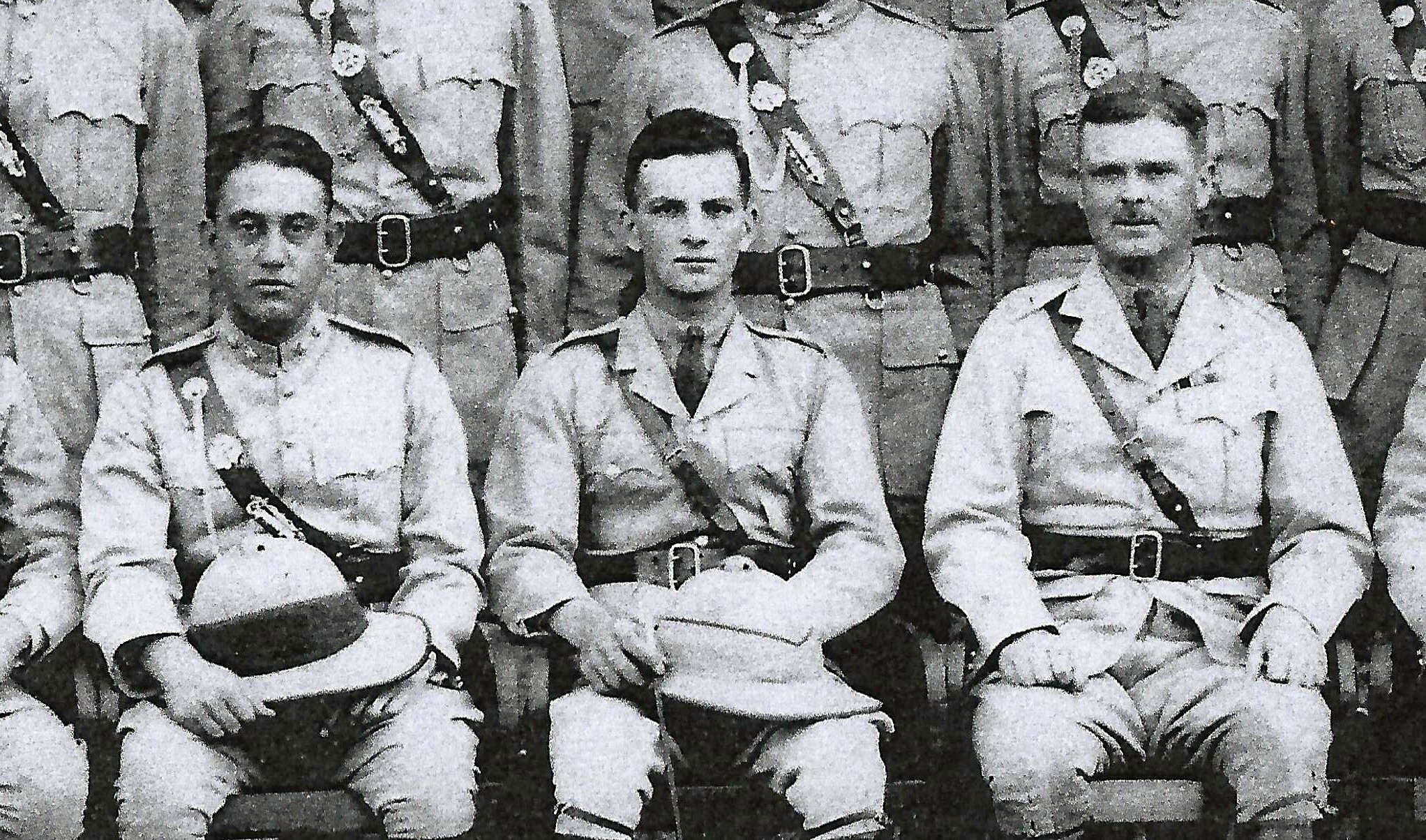

The 14 have long been known as “The Hooded Men” and have campaigned since their release in the early 1970s for an official acknowledgement they were tortured.

Their latest victory came last month when the Supreme Court ruled that the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) had acted illegally in failing to investigate the 1977 letter.

The court called the PSNI decision “irrational”, adding the men’s torture had been “deliberate policy” and “deplorable”. It was welcomed by the nine surviving “Hooded Men” – the other five having died waiting for such an investigation.

Six techniques

The 14 men were among hundreds arrested and interned by the UK authorities as part of a crackdown on suspected members of the Irish Republican Army. They were held in a purpose-built unit at Ballykelly army barracks in County Derry complete with noise-generating and monitoring equipment.

The men were questioned by a team of 15 Special Branch officers from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), who had been trained by the British Joint Services Interrogation Wing.

Dr. Robert Daly, who examined some of the men in 1973, found serious and long-term psychological disability, suffering and psychosomatic problems. The most common was “marked anxiety, fear and dread, as well as insomnia, nightmares and startle‐responses”.

The men were subject to the so-called “Five Techniques” – hooding, sleep and food deprivation, white noise and being spread-eagled in an intense “stress position”.

The men say the regular beatings they endured when they inevitably stumbled from the stress position amounted to a sixth “technique”. All have suffered long-term psychological injuries such as extreme anxiety, depression and PTSD.

For years, London has argued that these methods of “interrogation” did not amount to torture. But their practice by the British army was widespread.

Lord Balniel told parliament in November 1971 that the same methods had been used in other British wars in Aden (now in Yemen), Borneo and Malaysia in the 1960s. Declassified recently revealed British troops tortured dozens of detainees in Oman weeks before it happened in Ballykelly.

In fact, torture techniques were routinely practised by British forces in many other places, such as in Kenya and Cyprus in the 1950s. They provided a direct line to Northern Ireland in the 1970s and, still more recently, to the UK wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Authorised by ministers

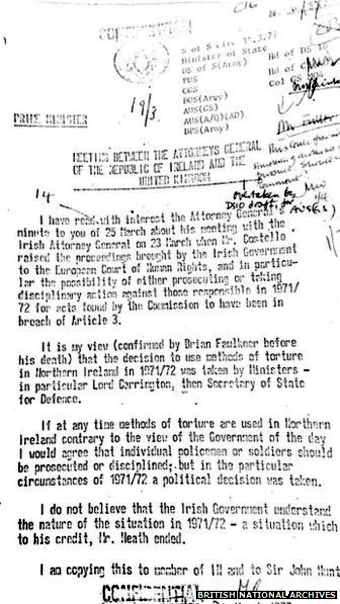

The 1977 “Rees Memo”, as the Supreme Court refers to the letter, was commenting on a legal challenge brought by the Irish state to the use of the “Five Techniques”.

Merlyn Rees states in his letter: “The decision to use methods of torture in Northern Ireland in 1971/1972 was taken by ministers, in particular Lord Carrington, then Secretary of State for Defence.”

Rees further states that no “individual policemen or soldiers should be prosecuted or disciplined” because they were merely following orders – his apparent implication being that, if anyone, ministers should face the courts.

The Supreme Court last month also scrutinised the rationale for the PSNI’s decision not to act on the Rees memo. It said the decision was rooted solely in a “seriously flawed” report compiled by a temporary researcher on contract to the police.

Jason Murphy, the Detective Superintendent who commissioned the report, and who was involved in the recent decision not to investigate claims of torture, was awarded the Queen’s Police Medal in the New Year’s honours list, despite the report being trashed by the Supreme Court judgement.

This report was compiled in 2014 at the request of senior PSNI officers in the wake of the Irish national broadcaster, RTÉ, transmitting the “Torture Files” documentary.

The ‘Torture files’

Without viewing the programme, the researcher for the police went to examine files at the National Archives in London. His instructions were “to verify the existence of the Rees Memo and any other documentation which may explain the context in which it was written and whether or not the use of torture had been authorised”.

The researcher’s report accused RTÉ and its journalist, Rita O’Reilly, of failing to put the Rees memo in context. The Supreme Court said this conclusion was an assumption that “regrettably” did not inspire confidence in his impartiality.

The police researcher further accused O’Reilly of wrongly claiming she had seen the memo because, he claimed, it had been “retained under secure conditions since 1978”. This, the researcher said, raised “interesting questions” about how she had gained access.

O’Reilly’s affidavit to the Court pointed out she had found the Rees memo in a different file from that examined by the researcher, had exhibited it to the court and broadcast it on screen in the TV documentary (which the police researcher did not watch).

The researcher also accused “groups and individuals” of seizing on the memo to justify claims of torture – a claim the Supreme Court said made “apparent” his “antipathy” towards claims of torture.

In accusing RTÉ of creating “a particularly biased, badly researched and misleading programme”, the court found “a lack of fairness” in the police researcher’s work. It said he had “a willingness to base conclusions on partisan assumptions rather than evidence”.

Sequence of events

The sequence of events leading up to the programme had been the discovery by the Pat Finucane Centre, a human rights group that investigates deaths during the Troubles, of documents in the National Archives.

These gave the location of the men’s torture and other previously undisclosed details, which were passed to RTÉ.

The broadcaster had then initiated its own investigation, leading to another archive, accessed through academics at the National University of Ireland in Galway, and at the National Archives in London where the Rees memo was discovered.

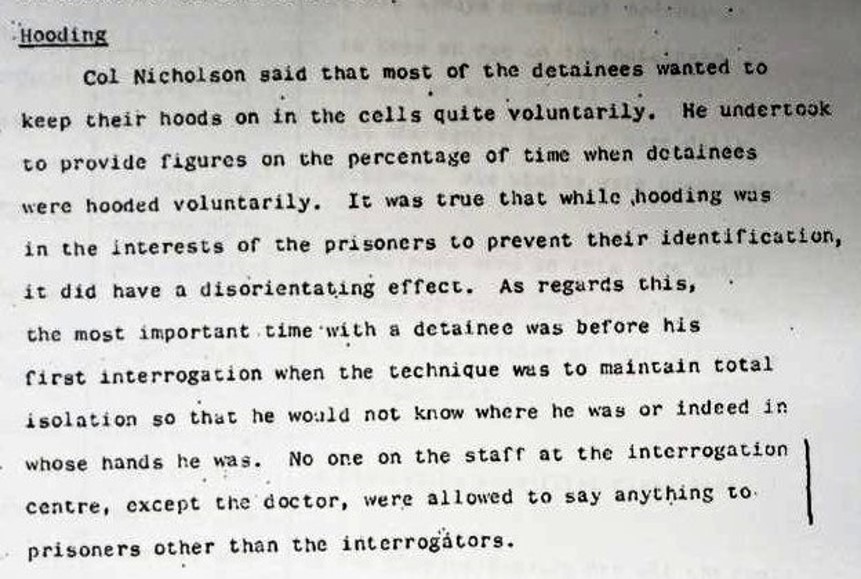

One bizarre aspect of the case on which the Supreme Court was not asked to adjudicate was a claim made by a military official in declassified documents, also discovered by the Pat Finucane Centre. This was that the 14 men subjected to the five techniques had voluntarily worn the hoods – some for longer periods than when forced to.

When approached in 2014 about this claim, Francis McGuigan – one of the nine surviving Hooded Men – was flabbergasted. In 2021, he still is. “It’s complete and utter nonsense”, he told Declassified.

“I’m 74 this month and five of us are already dead. The torture didn’t end when we were released from internment. The system seems incapable of admitting what it did to us”, he said.

The ball is now firmly in the PSNI’s court.

Lord Carrington went on to become secretary general of NATO and a minister in six Conservative governments. He died in 2018.

The torture allegations against British troops in Oman have not been investigated by any UK detectives, despite the Metropolitan Police having jurisdiction to probe war crimes abroad.