It was a freezing winter’s day in London in late 2019 when a curious concoction of military officials, security experts and journalists gathered for a hushed discussion at a prestigious defence think-tank.

Private armies were posing a threat to peace and delegates were asked to help find “realistic and workable solutions” for the international regulation of private military companies (PMCs).

As the author of a new book about British mercenaries, I was invited to attend the event on the condition that I did not name who said what.

It quickly became apparent that the concern of most participants centred on the Wagner Group, a shadowy group of guns-for-hire run by Russian special forces veterans who seem to be controlled at arm’s length by President Vladimir Putin and his Kremlin apparatus, as Daily Maverick has reported.

Wagner has triggered gruesome headlines with allegations that some of its employees beheaded a prisoner in Syria, that its own soldiers were beheaded by insurgents in Mozambique, as well as concerns it is fighting alongside a warlord in Libya.

However, the director of a British private security firm who attended the London event tried to allay concerns about his Russian rivals. “There is a great deal of hysterical reporting in the media,” he told participants. “In my view the Russian PMCs are doing the same as what we have done for the last 30 years but in a way that we cannot compete with commercially.”

He added, “I couldn’t compete with Wagner on price.”

The executive insisted: “I’m not a mercenary, I’m a businessman. I don’t conduct offensive military operations… Most of my business is with commercial entities who operate in volatile environments … Russian PMCs are assisting the Mozambique government to increase the capacity of their own armed forces to deal with insurgency.”

He argued that enough rules and regulations apply to his company, including the contracts he signs with clients that contain clauses prohibiting wrongdoing. “It’s a highly regulated industry already,” he said. “Regulation is between company and client. The contract is written in British law.”

The implicit message was unmistakable: any efforts by UK officials to rein in Russian mercenaries through international regulation could hamper British firms which have a similar line of work. And UK Plc would not appreciate such unintended consequences.

A former United Nations official at our event seemed unsurprised at the impasse, pointing out that neither Russia nor Britain have signed the UN’s convention against mercenaries since it was created in 1989.

Keenie Meenie

Britain’s ambiguous attitude towards mercenaries has been a long-standing feature of UK foreign policy since at least the mid-1970s, as became apparent to me while researching my book and film about Keenie Meenie Services (KMS Ltd).

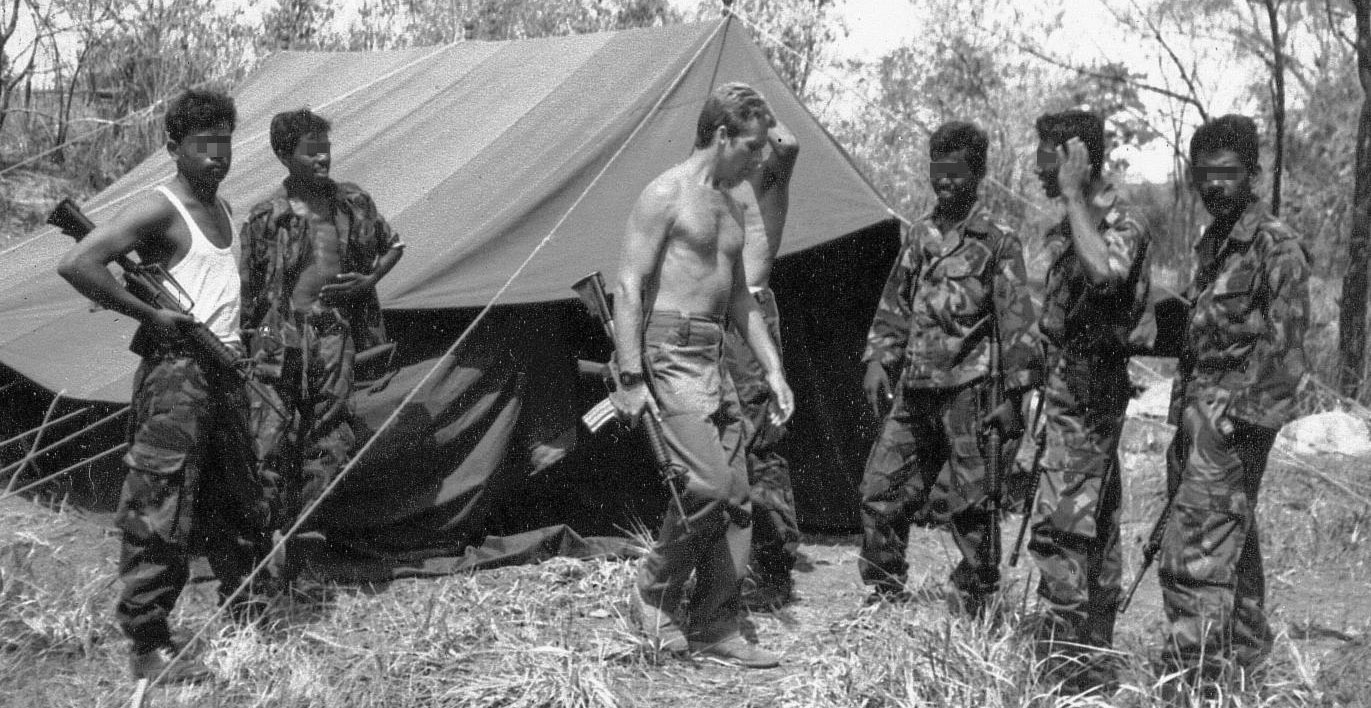

This was a mercenary company headquartered in London that supposedly took its mysterious name from Arabic slang for undercover or deniable operations. It was run by some of the UK’s most experienced special forces veterans who recruited retired British commandos and a smattering of South African, Rhodesian, New Zealand and Fijian personnel.

Together they blazed a trail of intrigue and destruction around the world from the mid-1970s until the late 1980s, when KMS directors finally became entangled in their own web that stretched at its peak from Nicaragua to Sri Lanka.

Throughout this tumultuous time, British authorities resisted pressure to introduce a domestic ban on mercenaries and only paid lip service to the international efforts underway at the UN. In fact, had politicians really wanted to stop KMS, the company could have gone out of business almost as soon as it started.

In 1976, following outrage at a massacre of British mercenaries by their own commander in Angola (an incident which did not involve KMS), Britain’s prime minister Harold Wilson asked a leading judge to investigate whether mercenaries could be banned.

However, it quickly became apparent that British officials themselves relied heavily on private security firms, particularly to guard embassies, and that anti-mercenary legislation could be a disastrous own goal. Declassified files from 1976 show that one Foreign Office staffer warned: “If KMS Ltd were legislated away en passant no comparable substitute protection would be available to the Diplomatic Service.”

This was despite colleagues being aware that: “Mercenaries are seen, in Africa in particular, in emotional terms, as a manifestation of continued white colonialist interference in affairs that no longer concern them.”

The Foreign Office’s Middle East Department insisted “our firm preference is still for no legislation at all” against mercenaries, adding that civil servants should present to ministers “the benefits of doing nothing at all”.

Covert action in Oman and Sri Lanka

As a result of this lobbying from inside Whitehall, no legislation was passed against mercenary companies. And at that stage, some of KMS’ activities seemed fairly benign, particularly bodyguarding British diplomats.

But there were already signs that the company could go in a far more dangerous direction, if there was no regulation to stop it.

“Up in the hills of Dhofar the new Special Force is trained by ex-SAS personnel in conditions of extreme extravagance,” Britain’s ambassador to Oman noted in 1976. Keenie Meenie was working in this former British colony, where it helped a young Sultan to suppress a left-wing revolution and cement his dictatorial grip on power.

This elite counter-insurgency unit in Oman was commanded by KMS personnel who also provided all logistical support “from pencils to machine guns, Land Rovers and boats.” The company’s experience of setting up and running a commando unit in Oman made it particularly attractive to other repressive regimes who wanted a similar squad to suppress their own internal opponents.

Sri Lanka was one such case. By 1983, the country was in turmoil, with the Tamil minority facing a pogrom from the ruling Sinhalese majority. As the Tamils turned to armed struggle to defend themselves, Sri Lanka’s right-wing President Jayewardene hired KMS to support his military, “pointing to the precedent in Oman, where KMS personnel had done exactly that.”

Initially, the company had a modest role, training a new police commando unit that specialised in riot control, VIP protection, hostage rescue and counter-insurgency. However, Keenie Meenie staff soon began to take on a more direct role in the conflict, as operations room advisers and then as helicopter gunship pilots. By 1985, the head of the Foreign Office’s South Asia Department was informed by his staff that “We believe only KMS pilots are currently capable of flying armed helicopter assault operations in Sri Lanka.”

This combat flying role concerned UK officials, who feared an embarrassing diplomatic incident should a British pilot be shot down, captured by Tamil rebels and subjected to a “show trial in front of a kangaroo court.”

For many months, KMS directors argued privately with Whitehall that its staff only flew as co-pilots while they trained Sri Lankan aviators. On rare occasions, they claimed, the helicopters were attacked during training missions or while providing logistical support and the more experienced British airmen had to take control and return fire, purely in self-defence.

Despite these claims, it gradually became clear to UK ministers that KMS pilots were routinely taking an active role in combat operations. Foreign secretary Geoffrey Howe told diplomats they were relying on a “very fine distinction” between KMS men being a co-pilot or a pilot on such missions, however he failed to introduce any new anti-mercenary legislation to address the issue.

Even today, figures in the private security industry continue to draw these kinds of granular distinctions when talking about their work. “In this industry I would always stop short of combat operations,” the unnamed British executive told the London event. He would of course provide logistical support in conflict zones, whereupon “if we come under fire we would return fire” – sometimes responding with thousands of bullets.

Echoing the assurances that Keenie Meenie gave British officials decades earlier, he insisted: “I can very clearly see the line between mentoring and combat, because I know combat.”

Atrocities against civilians

In Sri Lanka, people also know combat, even if they would prefer not to. A whole generation of Tamil priests has become adept at documenting human rights abuses, travelling from massacre to massacre in their flowing white cassocks. It was from their painstaking reports that I was able to piece together the damage inflicted by helicopters in Sri Lanka, many of them flown by KMS pilots.

Between August 1985 and May 1986, local priests recorded at least 50 attacks from helicopters. These involved methods of warfare as sinister as: throwing acid from a helicopter; shooting dead a one-year old child cradled in its mother’s arms, who herself lost an eye; burning houses and destroying farms and livestock; killing a baker and a priest; and firing on first responders as they tried to put a corpse into a van. These actions caused hundreds of people to flee and disrupted education for thousands of students.

KMS was undoubtedly involved in combat operations in Sri Lanka that resulted in atrocities against Tamil civilians, for which those responsible have never been held to account. There were pilots such as Tim Smith, and more importantly the company’s senior staff who oversaw its recruitment and tasking, men such as David Walker and Brian Baty – the latter who shouted at me to “bugger off” from his upstairs window when I asked him to comment on these allegations.

With no meaningful anti-mercenary legislation on the statute books, there is very little that these men need to worry about apart from bad publicity. This prospect is perhaps enough to deter others from pursuing a similar path to Keenie Meenie.

The businessman at our London event, after hearing my presentation, said: “If I’m linked with an atrocity personally, I will get journalists who will write a book about me and I don’t want that.” However, the idea that an investigative journalist such as myself, who took seven years to write a book on a shoestring budget, is a substitute for anti-mercenary legislation is faintly amusing if it were not so serious.

The businessman also argued that his company and others were governed by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), which has a code numbered 18788 that sets out a “Management system for private security operations”. This is not self-regulation, he insisted, but rather is a system policed by various independent auditors, including a person seated next to him that turned out to be a former colleague from another private security firm.

Ultimately, there is very little to stop another British company following in the footsteps of KMS and going down the slippery slope from bodyguarding to mercenary operations, especially when there continue to be world leaders and multinational corporations who will finance such activities.

“We do things other people don’t like to do, but without which the global economy won’t work,” the businessman reflected in London. He was of the opinion that the Wagner Group’s presence in African countries was inevitable. “If you want to extract natural gas out of northern Mozambique, you need private security.”

David Walker and Tim Smith did not respond to requests for interviews.