The abject submission of British authorities to the Master in Washington in the case of journalist Julian Assange is painful to observe but – unfortunately – not difficult to understand.

The roots go back to the Second World War, when Britain handed the mantle of world domination over to its former colony. The US had long surpassed the UK as an economic power and had displaced it from “our little region over here,” as Secretary of War Henry Stimson described the Western hemisphere. But it had not yet become a truly global power.

At the time, British officials were well aware that the UK was becoming a “junior partner” to the US, now subject to its will, which was often exercised crudely.

Given their own ample experience with imperial arrogance, brutality and hypocrisy, British diplomats could easily read between the lines when their American counterparts protested that US global domination is “part of our obligation to the security of the world…what was good for us was good for the world”, as Abe Fortas, a leading figure in the New Deal administrations, put it.

The British Foreign Office, parsing this apparent altruistic concern, concluded that Washington was, in fact, guided by “the economic imperialism of American business interests” and was “attempting to elbow us out…under the cloak of a benevolent and avuncular internationalism”.

UK officials continued that their American counterparts believe “that the United States stands for something in the world – something of which the world has need, something which the world is going to like, something, in the final analysis, which the world is going to take, whether it likes it or not.” What true believers in the historical profession call “Wilsonian idealism”.

From then, Britain takes it, whether it likes it or not. Things could have gone a different way at various points in modern history, recently if Jeremy Corbyn hadn’t been destroyed by a vicious media campaign. But today’s British authorities just take the orders and Julian Assange is one of the victims.

Intricate handover

While Britain had become the “junior partner” by 1945, the handover process had played out in an extended and intricate way.

One of the reasons why the now-famous Second Amendment of the US Constitution called for “a well regulated militia” was fear that “the Brits are coming”. The first foreign policy goal of the new Republic, apart from cleansing what became the national territory, was to take Cuba.

The British Navy was in the way. But, as the great grand strategist John Quincy Adams explained, over time British power would decline while that of the US would increase and Cuba would then fall into US hands by the laws of “political gravitation”.

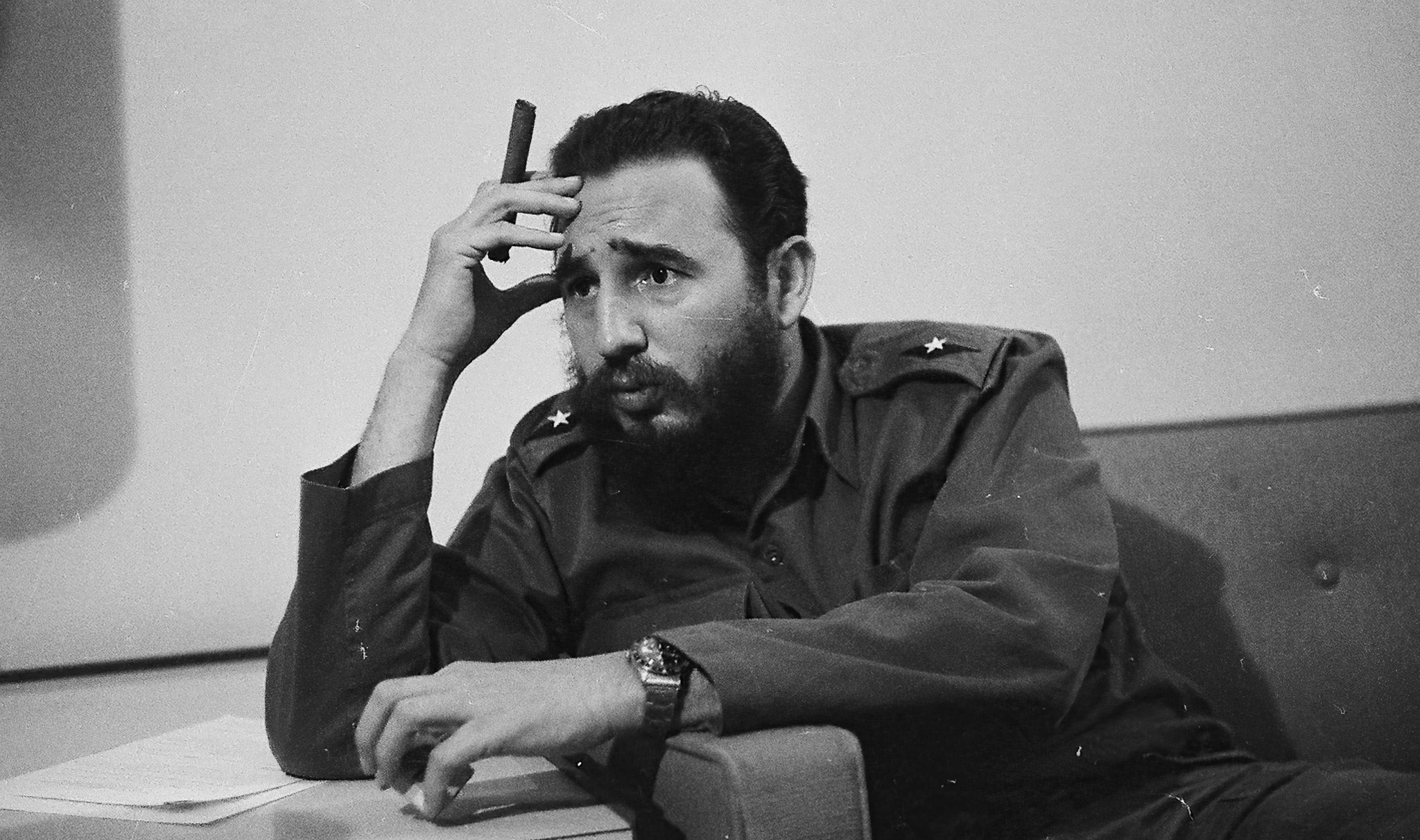

This did happen in 1898 when the US intervened to prevent Cuba’s liberation from Spain and turn it into a virtual colony. This is called “the liberation of Cuba” in preferred doctrine.

“The two criminal states also cooperated in exploiting the most vicious system of slavery in history.”

Nevertheless, the US was still a junior partner in the greatest narcotrafficking enterprise in history, which was run by Britain to force its way into China by poison and violence. The two criminal states also cooperated in exploiting the most vicious system of slavery in history, in the American South, to enrich themselves.

British wealth had already greatly benefited from piracy, Caribbean slavery, and the destruction and de-development of India after robbing its higher technology.

President Woodrow Wilson’s idealism was also illustrated by unceremoniously kicking Britain out of Venezuela when its rich oil deposits were discovered. President Franklin D. Roosevelt did the same in Saudi Arabia a few years later.

New nationalism

When the US picked up the mantle of imperial violence in 1945, the pattern continued, much as the Foreign Office anticipated.

One of the first acts was to ensure that “our little region over here” understood the rules-based international order that the new hegemon was imposing.

The State Department was concerned by the rise of the new “nationalism”, which held that “the first beneficiaries of the development of a country’s resources should be the people of that country,” an intolerable violation of the rules.

“The British model was pursued elsewhere by the US, also leaving a trail of destruction and misery.”

An Economic Charter was imposed by the US on the region that barred such deviation from sound economics, since enforced by bloody means, becoming a horrifying plague from Kennedy through Reagan.

The British model was pursued elsewhere by the US, also leaving a trail of destruction and misery, which continues up to the present. Always of course with the best of intentions, and graced by intellectuals who praised the “noble phase” of US policy with its “saintly glow” (New York Review, September 1997) as it murdered and destroyed.

This, again, followed the British model, as well as France, and other great benefactors of the human race.

Threat to freedom

In the 17th century, Britain pioneered a very limited form of modern democracy. That was followed, a century later, after a bitter struggle, by the establishment of the first free country of free men: in Haiti, where it was soon demolished by imperial force and never permitted to recover.

Another limited democratic revolution took place in the former British colonies in North America. This was stifled, however, as the Framers carried out a coup against democracy: The Framers’ Coup, to borrow the title of Michael Klarman’s study of the making of the US Constitution, the gold standard of scholarship.

As a means to induce the recalcitrant population to accept the coup, ten amendments were added, the Bill of Rights. The first Amendment barred Congress from passing any law “abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” Though that is a weak protection, it was a big step forward by the standards of the day.

But the major steps towards establishment of robust protection for freedom of speech and press took place in the twentieth century: first in Supreme Court dissents, then eventually in its decisions in the 1960s in the context of the Civil Rights movement.

“The major steps towards establishment of robust protection for freedom of speech and press took place in the twentieth century.”

The 1964 New York Times v Sullivan decision, which is now under threat by the ultra-reactionary Roberts Court, restricted the grounds on which public officials can sue for defamation.

Five years later, in Brandenburg v Ohio, the Court established that speech advocating illegal conduct is protected under the First Amendment unless the speech is likely to incite “imminent lawless action”. This protection is unparalleled to my knowledge, and, in my view at least, appropriate.

Law and practice are, of course, different matters. In Britain, the scandalous libel laws are one notorious example of severe infringement on freedom of speech.

The vast gap between law and practice is illustrated by the Assange case. Here Britain, adopting its usual role of “junior partner,” has been savagely supporting the effort of the inheritors of the Framers to infringe radically on freedom of the press. The media response has ranged from tepid to cowardly.

The precedent is all too clear. If the states that claim, with some justice, to be in the forefront of defence of freedom are granted licence to crush it when it interferes with state power and violence, the limited freedoms that have been won by popular struggle suffer a severe blow everywhere.