Official secrecy, said the Labour heavyweight politician and intellectual, Richard Crossman, who overcame fierce Whitehall opposition to the publication of his diaries, is “the real English disease”. He was writing in the early 1970s when industrial strikes, not secrecy, gave the country the sobriquet the “Sick Man of Europe”.

He was right. There are numerous reasons why it is time that the wall should be breached.

First, secrecy protects above all Britain’s intelligence and security agencies, preventing them from being held properly to account. They are exempt from the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act. Whistle-blowers and journalists who want to expose wrongdoing by the agencies are intimidated by the Official Secrets Act.

Yet MI6, the external security service, and GCHQ, the surveillance agency, are increasingly involved in military operations, especially with Britain’s special forces which are playing an ever more significant role.

The army’s special forces, the SAS, and its naval equivalent, the SBS, are covered by official secrecy rules even tougher than those that apply to the security and intelligence agencies, though the rules are honoured more in the breach than in the observance, not least by members of the special forces themselves when it suits them.

The distinction between war and peace is becoming increasingly blurred. It is increasingly difficult to monitor operations by special forces and the use of drones, raising serious questions about ethics as well as undermining international laws, including those covering war crimes and the Geneva Conventions.

The neglected Chilcot inquiry into the invasion of Iraq, which finally reported in 2016, revealed how British military commanders were frightened to tell truth to power – that is, to their political masters who sent UK forces to Iraq and Afghanistan ill-prepared and under-resourced.

The inquiry also revealed the extent to which MI6 misled ministers (who in turn misled parliament) about intelligence relating to Saddam Hussein’s weapons programme and links to al-Qaeda.

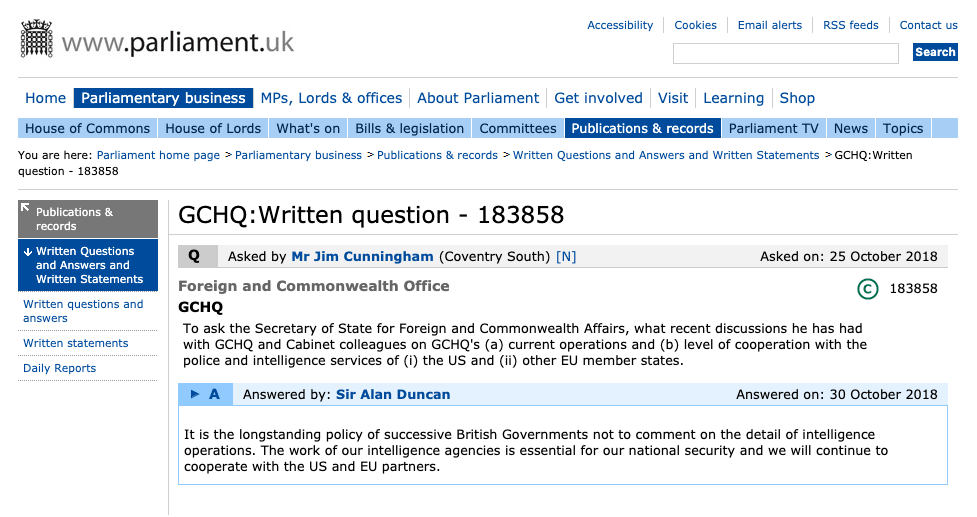

A rebuffed 2018 parliamentary question from then Labour MP Jim Cunningham requesting basic information about GCHQ, the UK’s listening post.

New laws, more data

MI5, the domestic security service, along with MI6, GCHQ, and counter terrorism police, are being given extra powers by new laws and are gathering more and more data on individuals. Yet the vast majority of terrorism attacks (some 30 out of 40) in the west in recent times have been committed by individuals known to the security and intelligence agencies, according to an independent study.

Intelligence chiefs complain their task is becoming increasingly difficult, with the growth of encrypted web sites and apps, making it harder and harder to find potential terrorists. They compare it to looking for a needle in a haystack. Yet the more data they amass, the more haystacks they build.

The definition of terrorism has been drawn wider and wider in a succession of statutes capturing more and more activities and beliefs giving the security and intelligence agencies and police increasing discretion over who they can target. Terrorism is equated with “extremism” and has included even those protesting against fracking and climate change.

In January 2020, counter-terrorism police in England’s south-east region included Extinction Rebellion in a list of ideologies that warranted people being reported to the Prevent programme designed to stop terrorist attacks. Though a police spokesman said the guidance was withdrawn after it was revealed by the Guardian newspaper, the home secretary, Priti Patel, defended the police’s decision, saying it was important to look at “a range of security risks”.

Laws and procedures designed to hold the security and intelligence agencies to account cannot keep up with developments in surveillance technology. That technology, facial recognition for example, has been shown by independent research to be unreliable.

Algorithms and artificial intelligence pose more threats to individual privacy and potential miscarriages of justice. Their inevitable growth makes effective independent monitoring of their use and effectiveness vital.

Misleading parliament

Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) made up of MPs and peers vetted by the prime minister, has been repeatedly misled by MI5 and MI6, notably over their role in rendition operations abducting individuals they regard as terror suspects and sending them to CIA prisons where they faced abuse and torture.

As prime minister, Theresa May prevented ministers and MI6 officers from giving evidence to an ISC inquiry in 2018 after the committee under the former attorney general Dominic Grieve in a damning report finally revealed the extent of MI5 and MI6 collusion in the torture of terror suspects by the CIA.

Current prime minister Boris Johnson was able to block publication before the December 2019 general election of the ISC’s report on Russian attempts to interfere in the EU referendum and recent general elections.

Secrecy extends even to the National Archives, guardian of the country’s history. The notorious section 3(4) of the (misnamed) Public Records Act gives Whitehall departments enormous discretion. They can withhold documents (subject now to a formal cabinet minister’s approval) “if, in the opinion of the person who is responsible for them, they are required for administrative purposes or ought to be retained for any other special reason”.

MI6 refuses to release its files to the National Archives even about operations of many years ago. While the CIA opened its files on the MI6-inspired coup in 1953 that toppled Muhammad Mossadegh, Iran’s first elected prime minister – an event still deeply ensconced in Iran’s collective memory – MI6 refused to comment.

Margaret Gowing, author of the first two volumes of Independence and Deterrence, the official history of the British bomb going up to 1952 (Whitehall is blocking further volumes), repeatedly regretted the deeply ingrained, wasteful, British habit of reinventing the wheel – governments unable to learn from past mistakes.

Language as a weapon

“National security” is often used to cover up embarrassment rather than genuine, serious threats to the country. When ministers and officials recognise that deploying the phrase would be an obvious exaggeration, they use an alternative argument, saying that it would not be in the “public interest” to disclose the information.

When faced with specific evidence about information disclosed in other countries about the activities of Britain’s security and intelligence agencies, Whitehall often falls back on a well-worn formula – that is to say “neither confirm nor deny”.

Language is a formidable weapon in the arsenal of official secrecy. Euphemisms are useful tools – as George Orwell observed, they are used in politics, war and business as instruments that “make lies sound truthful and murder respectable”.

The trick is never to make commitments and not “directly lie”. Thus officials deploy such phrases as “I hear what you say” and “that is speculation”. Matters are always “kept under review” or judged on a “case by case basis” – pet responses when officials are questioned about controversial arms sales, for example.

“The secrecy culture of Whitehall’, the late Sir Patrick Nairne, a widely respected mandarin once observed, “is essentially a product of British parliamentary democracy; economy with the truth is the essence of a professional reply to a parliamentary answer”.

Successive British governments have insisted that promoting human rights around the world is among their priorities. That is manifestly untrue. A priority has long been to increase arms sales.

Britain’s most lucrative markets are the Gulf states, led by Saudi Arabia, ruled by some of the world’s most authoritarian individuals and where executions are among the most common in the world. With the help of MI6, governments have embraced then helped to topple dictators (Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gaddafi) leaving a legacy of violence that continues to this day.

Far from protecting the nation’s security, obsessive official secrecy, an irrational addition to it, harms it, suppressing healthy debates about the real threats facing Britain and its citizens – notably from cyber attacks and violent terrorism – and how they should be met.

Obsessive secrecy prevents conscientious Whitehall officials from speaking truth to power, as the invasion of Iraq so disastrously showed. Deferential MPs remain ignorant. Effective security and intelligence agencies – and armed forces – are crucial. To be truly effective they need the public’s trust. Trust has to be earned, by transparency and willingness to be subjected to effective independent scrutiny.