Harry Kane has just scored a late goal, confirming England’s win over Germany in this summer’s Euros. We are sat under a marquee outside a pub near a main road in the nondescript village of Warton, Lancashire.

One of the punters stands up, lifting his Jägerbomb high into the air. “There were ten German bombers in the sky,” he sings as he dances awkwardly. “And the RAF from England shot one down.”

Warton has a population of two thousand people and on the surface there is nothing that sets it apart from any other English village. It has the primary school, nursery, Tesco Express, playground, corner shop, that make up the standard vista in small-town Britain.

It’s definitely not the kind of place to which you would drive 250 miles to watch an England game. But we’re here because Warton is, in fact, not just another sleepy corner of England. On the other side of the pub sits BAE Warton, a factory and aerodrome belonging to Britain’s largest arms company.

This factory, surrounded by lush fields and residential cul-de-sacs, is a key cog in the Saudi Arabian war machine which has been bombing Yemen since 2015, creating the world’s worst humanitarian disaster in the process.

But it appears this is a dirty secret most Wartonians are unaware of. “Nobody knows anything like that,” Gary Isaacs, one of the spectators at the pub, tells us after the game. “We only know what goes on here in Warton. We don’t know if the flights come in and then disappear out somewhere else.”

On the factory’s exports to Saudi Arabia, he adds: “No, I’d be quite concerned about that, to be quite honest.”

Isaacs actually lives next to the aerodrome itself. “Where we live we’re literally at the bottom of the runway,” he says. “You can see the whites of their eyes sometimes of the pilots when they’re coming in and some of them actually quite enjoy putting a bit of afterburner on and get all the alarms going everywhere we live.”

Before kick off we had checked out the runway. Around its perimeter stands high fencing and barbed wire with signs forbidding entry. As we approached, a Hawk fighter jet taxied down the runway and then took off. The noise was incredible, but the horses in the field next door barely noticed.

The Saudis have bought dozens of Hawks from Warton to train their pilots before they can fly the company’s more powerful Tornado and Typhoon aircraft. Thirty Saudi pilots have learnt to fly the Hawk in the UK since 2018.

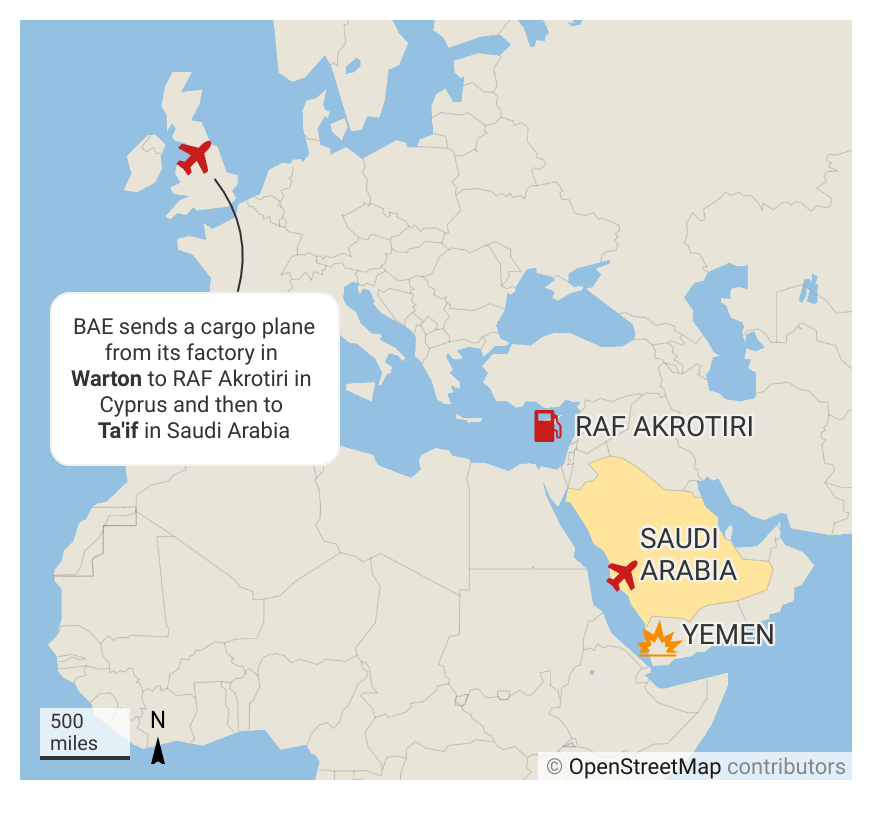

We are in Warton specifically to see a flight that leaves every Wednesday and which ends up at the King Fahad military airbase in Saudi Arabia. Although its cargo is murky, it is believed to carry supplies for the Saudis’ Typhoon fighter jet fleet.

Just after noon, a Boeing 737 cargo plane with West Atlantic emblazoned across it – the company that leases the aircraft to BAE for this weekly flight – comes into view in the distance. It continues towards us until it is in front of us, at which point it turns and revs its engines before disappearing into the sky.

It will land later in the day to refuel at RAF Akrotiri, a British military base on Cyprus, before moving on the next day to Saudi Arabia, where its contents will help keep the Saudi air force in the sky and ready for bombing missions in Yemen.

A former BAE worker has said that without the company’s constant support, the Saudi air force would be grounded within a fortnight. BAE has thousands of staff in Saudi Arabia, many maintaining its warplanes which have conducted the majority of over 23,000 airstrikes in Yemen in the past six years.

We then head on to Freckleton, a village on the other side of the aerodrome, to see if we can speak to some locals about this factory in their midst. But no-one wants to talk. Everyone either works — or knows people that work — in the aerodrome. And there is a wall of silence put up about what is happening inside.

Finally, a man sitting on a bench on the main street agrees to talk to us. Steve, an elderly chap who has lived in Freckleton all his life, tells us: “Yeah we know they’ve got big contracts with Saudi and various countries over the world where they go and obviously maintain the planes as well, get them up in the air and train the people that are going to fly them.”

He says there is “split opinion” locally about the “Saudi job”, adding “I don’t believe in war so if I’ve got an argument with somebody we can go outside and we can have a few fisticuffs and get it sorted and be friends the day after. Not killing people in cold blood. No, I don’t like it.”

The closest major city to Warton is Preston, one of the boomtowns of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. It has fallen on harder times since, but the BAE factory is presented as vital to reviving the area and to bringing jobs and investment. But not everyone is convinced.

On Fishergate, one of the main shopping streets cutting through the city, we speak with local Emma Quinn. She isn’t aware of the flight to Saudi Arabia which takes off 10 minutes up the road. “That doesn’t sound good at all to me,” she says.

“I think if people were aware on a more personal level then yeah, I think people would feel quite angry about it.” She adds: “We do a lot of dealings with Saudi Arabia, and they’re never really put in the picture when Yemen is talked about, which is a bit annoying really. But I think that this is something the government should be really sorting out.”

‘Innocent people have died’

Boris Johnson recently visited Warton and claimed the BAE site was part of his “levelling up agenda”. No journalist covering the visit seems to have reported the factory’s role in a war.

Back in London we spoke to Molly Mulready, who was a lawyer at the Foreign Office from 2014-19. She was responsible for giving legal advice in relation to exporting arms to the Middle East.

“Boris Johnson was very casual and jokey when we would go in to talk to him about arms to Saudi Arabia,” she told us.

“We would go in to brief him about Yemen and he would joke around and waste everybody’s time and it was a bit mind blowing because you know, you’re discussing civilian casualties, you’re discussing the fact that innocent people have died and that British supplied bombs have played a part in that.”

When Campaign Against Arms Trade took the government to court in 2017 over the export of weaponry from places like Warton to Saudi Arabia, Mulready was tasked with trying to defend it — something she now bitterly regrets.

“I’m so ashamed that I had anything to do with it,” she says, sobbing. “There have been tens of thousands of civilians killed in the bombing and there are millions of people who are food insecure. There are children in Yemen who are starving to death. The Saudis seem to have absolutely no compassion whatsoever.”

In Mulready’s opinion, the arms sales violate the UK government’s own licencing laws and contribute to Saudi war crimes — yet they continue, along with the weekly cargo flight we filmed.

“Boris Johnson was very casual and jokey when we would go in to talk to him about arms to Saudi Arabia”

Last month, on 18 September, three children were killed in yet another airstrike in Yemen. A few days earlier the Saudi ambassador to London, Prince Khalid bin Bandar, was being entertained by BAE’s chairman Sir Roger Carr at an arms fair.

Carr has had a good war, earning £700,000 a year from his part-time role representing BAE, of which exports to Saudi Arabia account for a substantial part of the company’s profitability. His company has exported over £17 billion worth of arms to Saudi Arabia since the war began.

Not surprisingly, the Saudi embassy and West Atlantic are tight lipped and did not respond to our requests for comment about exactly what cargo is on the weekly flight from Warton. BAE told us: “We comply with all relevant export control laws.”