The Shannon river, named after the Celtic goddess Sionna, is Ireland’s longest and largest. It winds 360 kilometres through the country, dividing western Ireland from its eastern and southern regions, before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean not far from Limerick, one of Ireland’s oldest cities, founded by Vikings in the 9th century.

This river had featured prominently in Irish social, economic and political history. It had been a major trade route for generations. In the 17th century, it was also a strategic military front amidst expanding colonisation of the island by the English. After war came famine, bubonic plague, Catholicism’s banning, and the indentured labour of thousands of Irish, some of whom were sent to work in other English colonies.

Though we landed at Shannon Airport on a cheap Ryanair flight from London, on the trail of contemporary, corporate empires. In the mid-20th century, the river’s name was borrowed for this new airport – and then for a new industrial zone, which we’d go to and which would inspire SEZs around the world, including in China.

The airport was built during World War Two. It had taken years to drain the boggy land on which it was built, on the river’s estuary. A 1945 deal between Ireland and the US required all American flights to land or stop here, and gave Irish airlines exclusive rights to serve Boston, Chicago and New York.

After the war, commercial airlines used the airport for transatlantic flights to and from the US and Canada. It became that era’s key ‘gateway’ to and from Europe; planes couldn’t carry enough fuel at that time and had to stop here before, or after, crossing the ocean. Numerous VIPs had flown through Shannon as a result, including JFK and Mohammed Ali.

We landed in Shannon late in the evening. We had only brought carry-ons and could have zipped through the building to the taxi rank outside but we took our time instead: this place was key to the investigation we’d just begun.

On a wall we saw a display of historic, black-and-white photos, from after the Second World War, and stopped to examine them. The excitement of a boom time seemed to radiate from these images – dignitaries and celebrities waving from staircases leading them off planes, or from luxury cars leading them through crowds.

All of the airport’s stores had closed by the time we arrived, including its duty free shop – the world’s very first. These stores are now as common as security checkpoints in airports globally, with shelves stocked high with items like alcohol, cigarettes and perfumes. But they’d started here, after a local entrepreneur named Brendan O’Regan convinced the government to pass a 1947 Customs Free Airport Act, exempting transit and embarking passengers, goods and aircraft from normal customs procedures.

The zone is born

This wasn’t O’Regan’s last big innovation, however – he would also be instrumental in setting up Shannon’s special economic zone, earning the tiny town a reputation as far away as Beijing. SEZs like the one we’d seen being built in Myanmar, and like thousands of others that had been established around the world, could trace their history back to this place. We had a long succession of interviews planned over the next few days, but our education began early, in a taxi on the way to our hotel.

Our driver was friendly and curious about what had brought us to his corner of Ireland. When we explained he chuckled “Bash On Regardless,” explaining that this was O’Regan’s nickname, based on his initials and his reputation for being a visionary entrepreneur who wouldn’t give up no matter what. He and the zone he had helped develop in Shannon were famous in the area. Our driver was the first of many people we met who seemed to know all of the details of this history. As we drove past a tiny town called Sixmilebridge he pointed out: “He was born right here”.

Everyone who lived in Shannon long enough seemed to know the story of O’Regan, who died in 2008 at 90 years old, and his famed entrepreneurial and determined spirit.

“He was a great person to motivate other people,” Tom Kelleher, an economist who worked with O’Regan in the late 60s and 70s, told us in his office in nearby Limerick. “Anything was considered, no matter how outlandish.”

Born in 1917, towards the end of the first World War, as a young man, O’Regan had travelled abroad to study hotel management. In the 1940s he worked in the catering business in Shannon. But he was best remembered for being a ‘visionary’ and serial entrepreneur – and for transforming this area of Ireland through his most influential invention: the Shannon Free Zone, established in 1959.

At that time, Shannon’s airport – and the town around it – was in trouble. Aircraft technology was advancing, and it would no longer be needed for refuelling on transatlantic flights. Instead, planes that were increasingly able to travel longer distances looked ready to bypass and simply fly over the area.

The town faced economic collapse. But O’Regan, the story went, was not ready for this to happen, and famously argued that Shannon would have to ‘pull the aeroplanes out of the sky’. And so he appealed to the government with a dramatic proposal to carve out the ‘free zone’ territory, and offer foreign investors freedom from onerous regulations and taxation from the central government in Dublin, if they moved there, created new jobs, and helped O’Regan prevent the town’s extinction.

In exchange for setting up shop in the zone, foreign investors were given benefits like special tax holidays, tariff reductions, and grants for research. Companies that accepted these offers, and moved to the zone, included a subsidiary of the De Beers diamond giant as well as Zimmer, which makes medical products including prosthetics.

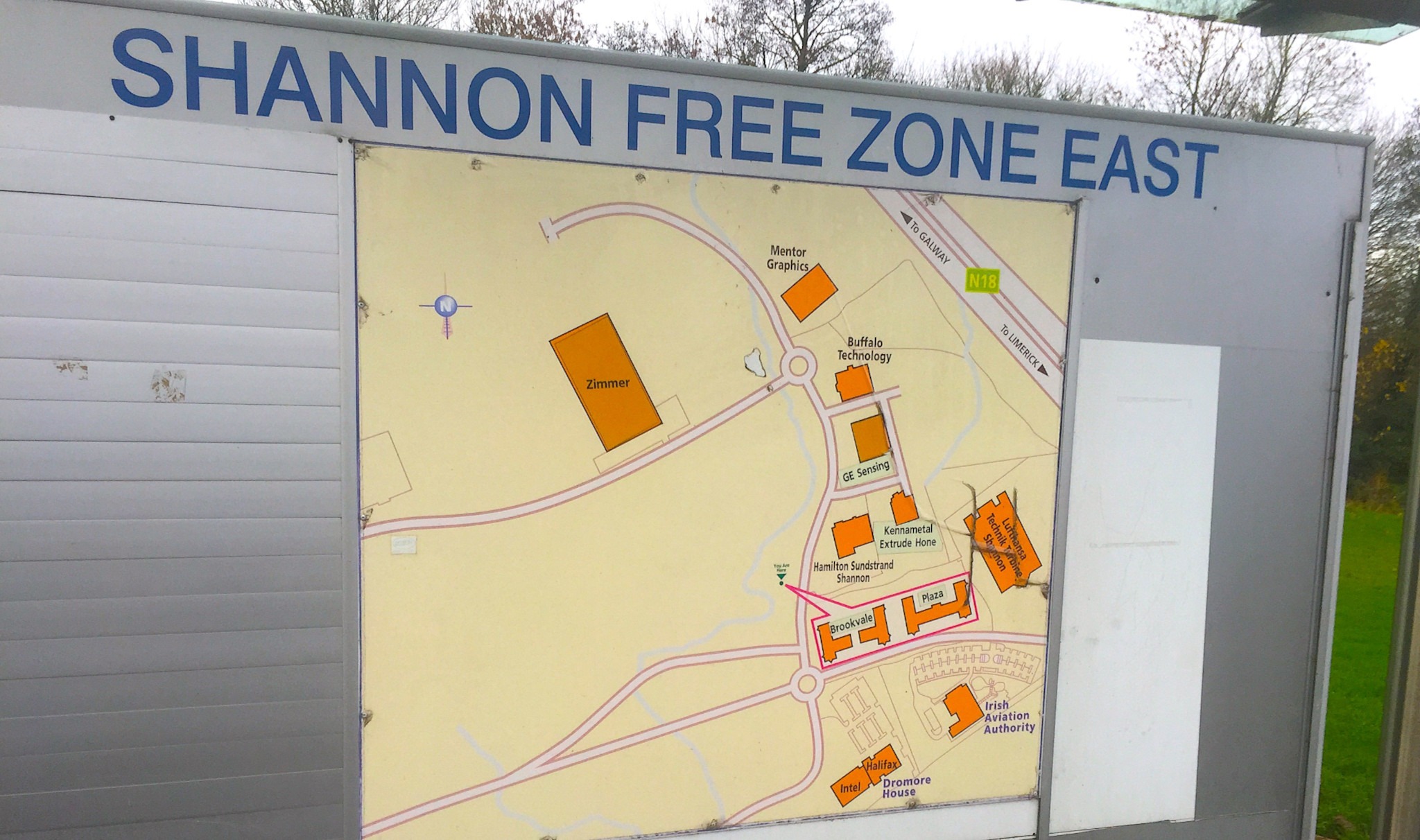

Next to the airport, the Free Zone covered about one square mile of land – though its influence internationally had been disproportionate. O’Regan’s innovation would inspire a growing number of other countries, companies, and international institutions to get involved in similar zones set up around the world.

‘The middle of the world’

The next morning, we drove to the zone. Walking through the gates, we passed large

factories and office buildings, but found few people to talk to. Most were busy working inside. Nearby, just outside the zone, we found a café and a small convenience store.

We went inside for a coffee and, at the table beside us, met Mary, 63, a talkative retired school principal who was chatting with a friend. She nodded vigorously when we asked her if she knew the story of O’Regan, the airport and the Free Zone.

Mary, who was born in Shannon, said it has been an exciting place to live. Because of the airport – which, thanks to the Free Zone and the traffic that it brought, did not end up closing – “we thought we were in the middle of the world!” she exclaimed. “I remember when President Kennedy came through, oh my God, the whole country stopped. Thousands of people went to the airport, it was amazing”. She chuckled. “It wasn’t quite the same when Ronald Reagan came”.

While the airport brought celebrities to Shannon on stop-overs, the zone brought new waves of international visitors, she explained – from corporate executives to government officials studying the development. “Even at my own school, we would have children from all over the world because their dads or moms were working or doing research in Shannon”, Mary recalled. “They might just come for a year, they might come for six months, they might come for five years, but we would have people from all over”.

O’Regan’s plan to transform Shannon into a hub for foreign investors led to the development of Ireland’s first new town in more than 200 years: Shannon Town, built on reclaimed marshland to house workers at the area’s new factories.

Paul Ryan, an economic consultant who grew up in this town, described it to us as “built from scratch and very much Milton Keynes-esque: the 1960s approach of, ‘Let’s turn it around, make the back of the house the front,’ all of these green areas, common areas – it was all very much in that style”.

Ring-fenced

When we visited, Shannon was still a tiny town, with a population of just 9,673. Though foreign companies did open up shop in the Free Zone, the town’s size never truly boomed, as many workers commuted from nearby cities like Limerick, as well as from villages like Sixmilebridge where O’Regan had been born.

By the early 21st century, zones like these had spread worldwide, from Argentina to Cambodia. Many had also been set up with advice from Shannon consultants, like Ryan, who worked for Shannon International Development Consultants (SIDC).

He told us that an attraction of these zones is the possibility to test policies in one area, before rolling them out nationwide: “Let’s say you want to try something, in a developing country, and you want to introduce new ways of doing business … having a zone, having an area that is ring-fenced and set aside from the rest of the economy, where you can try new approaches, is part of what makes it work”.

Ryan believed the town stayed small precisely because of its success in attracting foreign investment to Ireland. “Shannon grew to a certain point, and then what worked in the free zone could be applied to the rest of the country,” he said. “The need to have Shannon, this controlled area, went away.” Though, he was quick to add: “Shannon continued to be an excellent brand – even today it is a big name”.

One of the keys to Shannon’s success, he stressed, was the development of Smithstown, a nearby industrial estate and satellite location for mainly Irish businesses who became sub-suppliers to larger businesses in the free zone.

“You have to provide the Smithstown, you have to provide that indigenous industry starting point,” he said. Otherwise, local businesses might not benefit.

This made sense, though it was not what we would see on the ground around contemporary zones across Asia – where ensuring that these developments benefit local industries and communities did not seem to be high on the agenda.

Symbolic Shannon

Since 2005, Shannon Free Zone has had the same 12.5% corporate tax rate as the rest of Ireland. Now most businesses in the zone are in services, not manufacturing. It had become harder and harder to tell what special perks investors received for being in the zone, as these became national policy and spread across the island.

“The nature of the business has changed and over time the fence that was around the zone, and the custom control points, have disappeared”, said Kevin Thompstone, president of the Shannon Chamber of Commerce. We met him in an office at a shopping mall in town. Thompstone showed us a miniature model of Shannon, with tiny replica buildings. The fences around the zone, and those customs controls, he explained, had been “originally set up because of the 0% tax rate, that then was extended to other parts of the country”. Over time, he told us, “the fences came down and the benefits of a free trade zone were no longer so relevant because most of the exports were going to the EU, which was duty-free anyway. Really, today the Shannon Free Trade Zone name that you see on the entrance, is there more for marketing”.

At the airport, in the office of Shannon Group plc, a Irish state-owned company in charge of developing the area, we met strategy director Patrick Edmonds who told us a similar story. “There is [now] very little differentiation that we can achieve as a general purpose free zone, so that isn’t going to cut it”. For such strategists, this posed the question: “Ireland is already an attractive location [for investors] for national-level reasons. So how do we actually differentiate Shannon?”

Until 2004, a state-sponsored company called Shannon Development was also responsible for many town and government services that would otherwise have been provided by local authorities. At that point, such functions were transferred to the local county, though the company retained authority over the free zone itself.

When we arrived in Shannon, the airport still operated regular passenger flights to and from cities like London, New York, and Warsaw, as well as some seasonal flights to places like Boston and Frankfurt. It had remained a key site for the US military, too.

American war

The US military had used Shannon for stopovers during the first Gulf War. After the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks, it was used to invade Iraq. In 2007, the Irish Human Rights Commission reviewed evidence suggesting that the airport was also being used for the refuelling of CIA ‘extraordinary rendition’ flights to secret detention and interrogation sites.

One example it looked at was the case of Kuwaiti-born German national Khaled El-Masri, who was flown to Afghanistan and tortured for months (with no evidence ever emerging, or charges made, in relation to any terrorist activities). “The aircraft involved in his abduction,” said the Commission, “had stopped in Shannon.”

The airport’s military business was controversial because Ireland had remained outside of NATO and had a policy of military neutrality. Throughout the 2000s, protestors targeted US military planes at the airport, while the transit of troops generated significant revenues for Shannon, helping to offset losses from fewer commercial flights. This was another dynamic that put this place in the headlines. An estimated 2.5 million US troops had passed through here since 2001.

An activist group called Shannonwatch had been campaigning against the use of Shannon airport by the US military on their way to and from wars in the Middle East. On a sunny morning we met Edward Horgan, who was a long-time activist with this group, who walked with us to the gates of the airport. “That’s one right there”, he told us, peering through binoculars at a military plane across the runway.

“The bulk of troops would have passed through on chartered civilian aircraft [but] we do know that those troops are carrying those weapons with them on the planes”, Horgan told us, standing by the thin metal fence that surrounded the airport. Among the planes activists had documented here, he said, was the Lockheed C-130 Hercules military aircraft, which comes in various, including weaponised, versions.

Walking around Shannon, it was hard to square its significant international influence with its tiny size. But this place had been touched in many ways by grand currents that had driven global events since the end of World War Two: from the expansion of international investment and SEZs to US military operations.

We were also struck in Shannon by the role of symbolism in the zone’s story. We had heard how the free zone was no longer such an exceptional space, given national policy changes, but that maintaining it and its name was useful for ‘marketing’. We had heard similar things before – including in Myanmar where the World Bank’s IFC had said investing in a five-star hotel would send an important ‘signal’ to foreign business people that they were welcome and would be made comfortable in the country.

Inspiration for China

SEZs had boomed globally since the establishment of the Shannon Free Zone, including with help from international institutions like the World Bank and Irish consultants. As early as the 1960s and 1970s, consultants from Shannon in Ireland were working on designs for new free zones in Taiwan, Malaysia, Egypt and Sri Lanka. There were also training courses organised in Shannon, attended by representatives from dozens of governments around the world, on how to develop these zones.

Jiang Zemin, who would later become China’s president, visited Shannon as a junior customs official in 1980 and took one of these three-week training courses about these zones. At that time, China’s leader Deng Xiaoping was starting to experiment with opening up the country’s economy to international, private capital. The Shenzhen SEZ – China’s first – opened the same year that Zemin returned from Shannon.

In 2005, Wen Jiabao, then China’s leader, became the latest in a long line of high-level Chinese dignitaries to come and pay their respects to the birthplace of the SEZ model they thank for their country’s rise to economic superpower status.

Thompstone, at the Shannon Chamber of Commerce, told us that in the runup to Wen’s 2005 visit, the Chinese ambassador had asked their Irish hosts to make time for him to pause for reflection on the “plateau” – a spot on the town’s Tullyglass Hill that overlooks the grey, windswept, industrial estate that is its historic free zone.

“This was the leader of China, a country with a population of 1.3 billion!” Thompstone exclaimed, pausing at the memory of this incongruous spectacle – the political ruler of this world superpower apparently humbled by Shannon, his tiny town in western Ireland. “To us it was just this nondescript place on the top of a hill, but for the Chinese, they wanted to see where it all started”, Thompstone recalled.

Undoubtedly, Chinese leaders took the SEZ model “to a much bigger scale than anything that we did”, he continued, encouraging us to join him in marvelling at this story. “The Chinese were able to develop and grow on the back of this model from this little place called Shannon … and there’s something in their spirit that says, ‘You know those people who went before us, where did it start? Where did it come from?’”

The model continues to consume the world. In 2020, the British government announced its intention to create a number of so-called ‘Freeports’ across the UK, with the aim of boosting trade and investment.

It describes them as “special areas within the UK’s borders where different economic regulations apply” including bespoke “tax and customs incentives”. It sounded no different from Shannon’s innovation over 70 years before.

This an edited extract from Silent Coup: How Corporations Overthrew Democracy which is out this month from Bloomsbury Academic.