The UK government has announced it is increasing the number of nuclear warheads for its Trident submarine fleet to 260. But just as worrying is who Britain is now threatening to use them against.

Until now, the size of the UK’s nuclear arsenal had been on a downwards trajectory. Britain was set to reduce the number of warheads from 225 in 2010 to 180 by the mid-2020s, a decision made by David Cameron’s coalition government of 2010-15.

This downsizing was part of three decades of gradual reductions in the UK’s nuclear arsenal, which included retiring its free-fall nuclear bombs in 1998. Britain now has roughly 195 warheads, each about eight times the power of the Hiroshima bomb.

Even more concerning is that Johnson’s government has changed Britain’s stance on the use of nuclear weapons. The new UK policy, unveiled in its long-awaited “Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy”, sits more easily in the framework of “usable” nuclear weapons which were produced and deployed in former US president Donald Trump’s last year in office.

The UK now reserves the right to use nuclear weapons not only against nuclear threats but against enemies possessing chemical and biological weapons or “emerging technologies that could have a comparable impact”.

The British government is also threatening to use its nuclear arsenal against non-nuclear weapons states that are said to be heading in the direction of acquiring nuclear weapons — or, as the Integrated Review puts it, those states judged to be “in material breach of [their] non-proliferation obligations”.

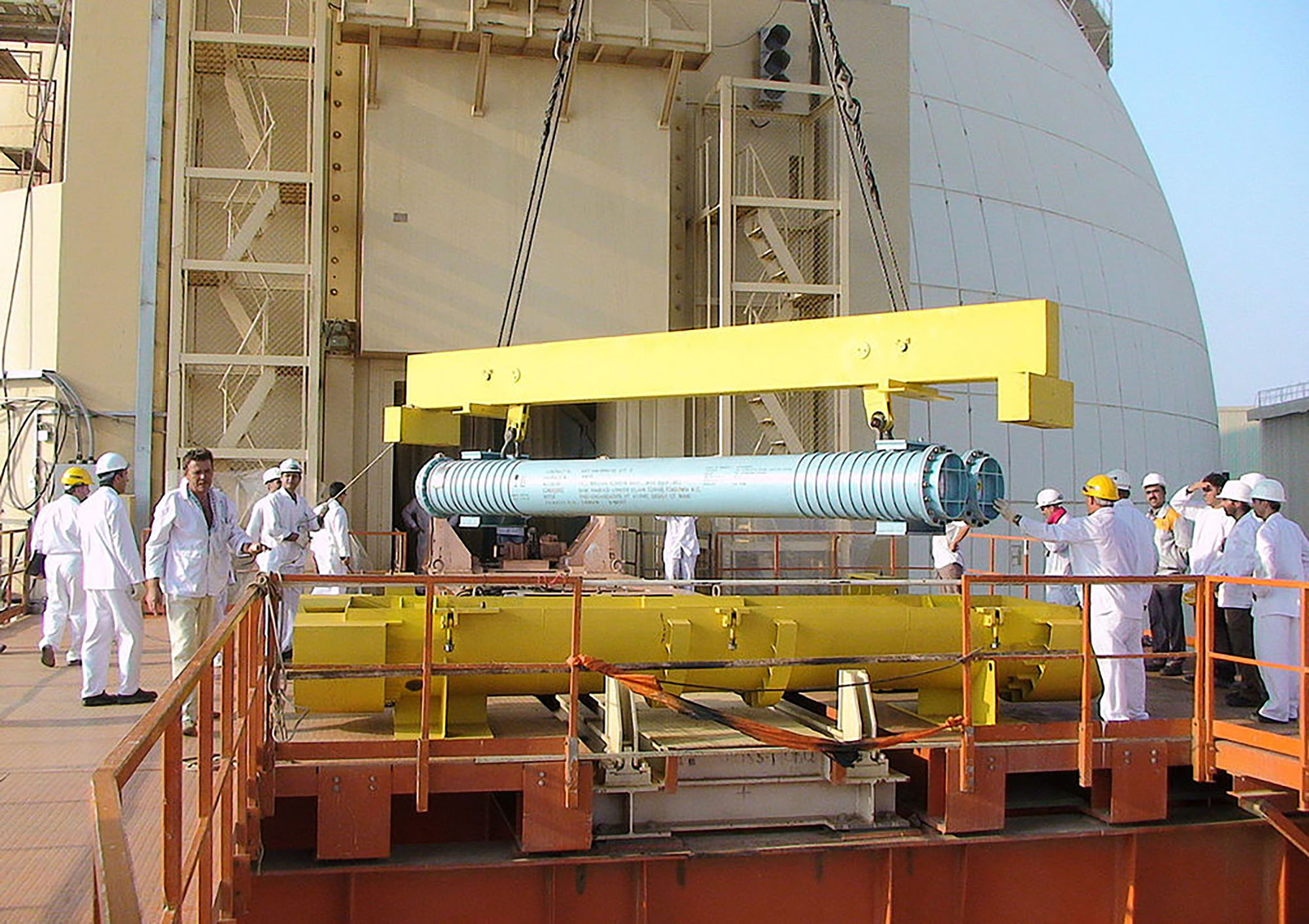

This is a major change in policy and it is easily understood as a thinly veiled reference to Iran. The British government has repeatedly said that “Iran must never develop a nuclear weapon”.

The Integrated Review says the UK will embark on “a renewed diplomatic effort to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon”. But London appears to be sending a message to Tehran that is not just about diplomacy.

Breach of international law

It had not been expected that the UK would increase its nuclear arsenal by over 40%. The decision has given rise to international criticism and is at odds with the renewal of the New START Treaty by presidents Biden and Putin earlier this year, which continues bilateral nuclear weapons reductions between the US and Russia.

The legality of Britain’s changed policy was rapidly called into question. The Office of UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said the UK decision was contrary to its obligations under Article VI of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) — in other words, it is illegal under international law.

This triggered the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament to seek a legal opinion from experts, who found that the UK is indeed in breach of the NPT.

Article VI specifies that signatories undertake to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures” towards disarmament. The legal opinion finds that an increase in nuclear warheads does not constitute a good faith intention to negotiate and that “good faith” is not just mood music — it has legal status and requires concrete outcomes.

The legal opinion also finds that the UK’s change in stance on the use of nuclear weapons is in breach of international law. Any use of nuclear weapons would violate international humanitarian law and a whole raft of legal obligations relating to the environment, proportionality, distinction and other matters enshrined in law.

What’s more, others breaking international law does not make it legally acceptable to do so in return. The NPT is actually very simple — it requires countries that have nuclear weapons to disarm, and those that don’t have them not to get them.

The UK government routinely claims that its nuclear weapons are not illegal. It states: “The UK’s nuclear deterrent is fully consistent with our international legal obligations, including under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons”.

Technically the weapons themselves are not illegal, but the government’s retention of them is — as would be their use or threat of use — as the legal opinion clearly demonstrates.

All UK governments since 1970, when the NPT came into force, have had a twin-track position — on the one hand pledging commitment to the goals of the NPT, and on the other insisting that the UK’s own nuclear weapons are both essential to its own security and acceptable under the NPT.

As prime minister, Tony Blair attempted to reinterpret the NPT to mean that the five nuclear weapons states signatory to it (US, China, Russia, France and the UK) were allowed to be nuclear weapons states and the emphasis of the Treaty should be non-proliferation. This didn’t cut any ice with the majority of states but de facto this is the situation.

And because the nuclear weapons states do not comply with the NPT it has led to further attempts, led by the countries of the global south, to use other legal instruments to get rid of nuclear weapons — notably the UN’s Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) which became international law in January of this year.

Replacement of Trident

The outrage from political quarters over the UK’s increase in warheads suggests the downwards trajectory in nuclear numbers had received general approval.

But some who express outrage also back the replacement of the Trident nuclear weapons system, indicating they think some new nuclear weapons are good, but just not too many.

Legally speaking though, it’s not just new warheads that breach international law, it’s the whole Trident replacement project as well.

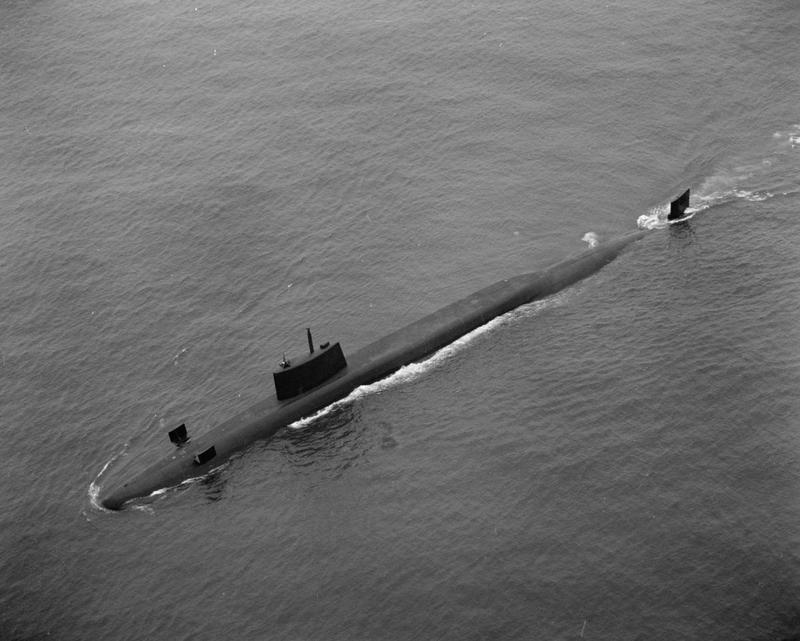

Rather than disarming, the UK is in the process of replacing all three component parts of the Trident system: the warheads, the missiles that carry them to their targets and the submarines that carry them around under the sea.

When Blair’s government first pursued Trident replacement in 2005, the law firm Matrix Chambers gave a legal opinion finding that it would be a material breach of the NPT because of the Article VI requirements to pursue disarmament.

Bizarrely, British governments always assert their unflinching commitment to the NPT, and the Integrated Review is no exception. It states: “We are strongly committed to full implementation of the NPT in all its aspects, including nuclear disarmament”.

Sadly, that’s just not true. Indeed our government — with all its talk of the “rules-based international order”, the super-soft power of the BBC, its leadership in diplomacy — completely ignores the Treaty.

Its decision to increase the arsenal has fired a Trident missile through any pretence at fulfilling its legal obligations.

Despite its non-compliance with the Treaty, the Review is quick to assert that “there is no credible alternative route to nuclear disarmament” except the NPT. This is a thinly veiled reference to the government’s hostility to the new TPNW.

Britain’s decision to increase its nuclear arsenal clearly demonstrates why so many other countries have given up hope in the NPT process which has been rendered meaningless by the actions of states such as ours.

Johnson’s decision to increase Britain’s nuclear arsenal is a serious problem. It’s not just that we would rather the money was spent on something more useful, or that this flagrant breach of the NPT may encourage others to pursue nuclear weapons.

It is also a question of what kind of world we want to see, what role we want Britain to play and what it actually stands for. Rearming with weapons of mass destruction is not something that we can accept.