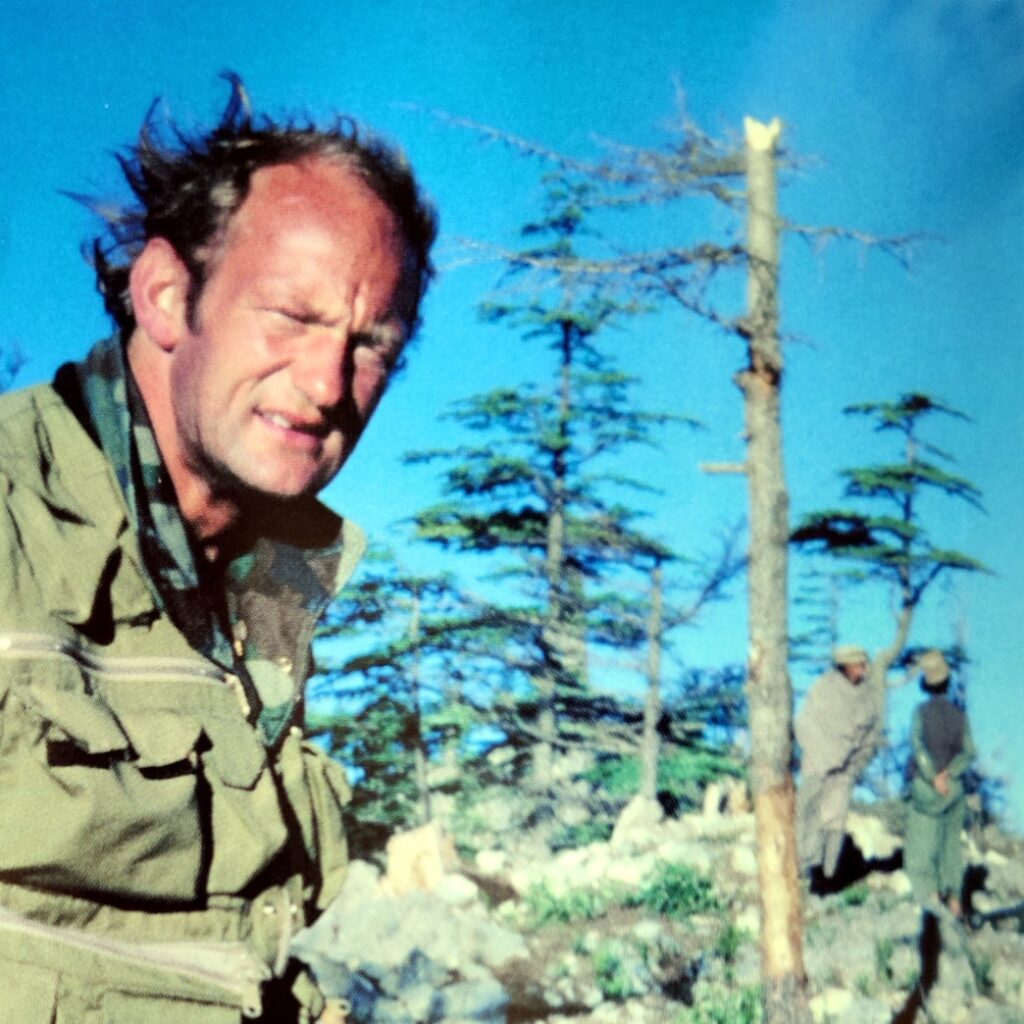

Andy Skrzypkowiak was filming the Soviet Union’s occupation of Afghanistan for the BBC when he went missing in October 1987. The 36-year-old SAS veteran, raised in Britain by Polish parents, was later pronounced dead.

His skull had been crushed with a rock as he slept. He left behind a wife and young daughter. The killers have never been brought to justice.

It wasn’t the Soviets who murdered Andy, but an Afghan fundamentalist group: Hezbi Islami (Islamic Party). They were led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a notorious warlord and Western ally.

US intelligence wanted Hekmatyar to drive Soviet forces out of Afghanistan as part of the Cold War against communist Russia.

The CIA gave Hekmatyar’s group $600 million during the 1980s. No other Afghan militia, who were known collectively as the mujahideen (Muslim fighters), received as much money.

Hezbi Islami jealousy guarded their pole position and tried to prevent other guerrillas gaining publicity. They probably killed Andy just because he had filmed a rival group.

‘Hardline, Islamic revolutionary’

Three decades on from the horrific murder, Declassified has found new evidence of British government contact with Hekmatyar both before and after Andy’s death.

Such liaisons may have helped defeat the Soviet Union but they also gave rise to future terrorism. After 9/11, Hekmatyar joined Al Qaeda and Taliban attacks on NATO troops in Afghanistan.

This should not have been a surprise. Hekmatyar’s Islamic extremism was already apparent during the Cold War.

John Fullerton worked for MI6 from 1981-83 and met many mujahideen leaders sheltering over the Afghan border in Pakistan. He told us Hekmatyar was a “nasty character” and “very hardline”.

Files found at the UK National Archives show Britain’s Foreign Office agreed. They also regarded him as a “hardline, Islamic revolutionary”.

Hekmatyar’s group taught Saudi militant Osama Bin Laden how to fight in Afghanistan during the mid-1980s, shortly before he founded Al Qaeda. Around the same time, Hekmatyar asked the British embassy in Pakistan for a UK visa.

Alastair Crooke, an MI6 officer at the embassy, dealt with his application. Files show Crooke “offered to arrange calls” for Hekmatyar to meet British officials while in the UK.

Warlord in West Hampstead

With British visa in hand, Hekmatyar travelled to Manchester and Derby to address Muslim students in 1986. He also held a press conference in London and met a diplomat from the Foreign Office’s South Asia department.

The pair sat “in the rather incongruous surroundings” of a “spacious West Hampstead residence” that belonged to a friend of Hekmatyar.

The warlord “seemed well disposed” and briefed the British diplomat on events in Afghanistan, which were relayed back to Crooke in Pakistan.

Crooke has previously told Declassified by phone that Whitehall’s contact with Afghan mujahideen during the Cold War remains “highly sensitive”. Margaret Thatcher’s file on her dealings with Afghan warlords as prime minister is still sealed.

Crooke did not respond to further questions we sent by email.

Visiting the United Nations

Despite this ongoing secrecy, Declassified has found Hekmatyar had contact with almost all levels of the British government in the 1980s.

This ranged from an MI6 officer like Crooke right up to Thatcher’s foreign secretary, Geoffrey Howe.

At its peak this relationship saw Britain invite Hekmatyar to attend the United Nations in New York in the mid-1980s. This was because he made a “convincing case against the Soviets”.

British diplomat Sir Stewart Eldon told a biographer: “I well remember that I had the joy of spending a couple of one week periods of parading Afghan resistance fighters around the UN, much to the annoyance of the Russians.”

He added: “It was thought that it would be a good idea to bring them to New York and peddle them around the various delegations to have them say their piece.”

Eldon said inviting Hekmatyar to the UN was “slightly surreal” as he “subsequently went off to kill a BBC television cameraman.”

Murder in the mountains

Not long after Hekmatyar’s visit to the UN, his group murdered Andy Skrzypkowiak in October 1987.

His widow Christine Gregory told the Guardian: “Andy was determined to show by his filming what was happening under the Russians in Afghanistan. It is sickening that he was murdered by the very people he was there to help. He had tremendous sympathy for them.”

Andy had served with the elite SAS in Northern Ireland and Oman before becoming a freelance cameraman. He worked for some of Britain’s most famous broadcasters, including ITN’s Sandy Gall.

At the time of his death, Andy was freelancing for the BBC on his 15th trip to Afghanistan and had filmed a rival mujahideen group led by Ahmed Shah Massoud, a more moderate rebel leader.

Massoud is often described as being favoured by MI6 and the Foreign Office. Britain’s ambassador to Pakistan, Sir Nicholas Barrington, mentioned in his memoirs: “we helped Massoud with communications”.

However, Barrington said he never actually met Massoud. By contrast, Barrington had “satisfactory meetings” with the more extreme Hekmatyar, “who spoke good English…[and] had a sense of humour.”

Such ties between the Foreign Office and Hekmatyar may have made him feel his group could kill a British journalist. And get away with it.

Inviting Hekmatyar to the UN was “slightly surreal” as he “subsequently went off to kill a BBC television cameraman.”

Sir Stewart Eldon

Hekmatyar later told The Times that the British government had “never” made any representations to him regarding Andy’s murder.

But Barrington claims he raised the killing “at length” with the warlord. He expressed concern in a telegram “at the high-handed way Hekmatyar had brushed off any responsibility” for his death.

International concern

By 1988, French diplomats were increasingly concerned at Hekmatyar’s “thuggish behaviour”. Fellow mujahideen leaders complained that his group was “robbing other resistance groups inside Afghanistan instead of fighting the Russians.”

US security officials privately acknowledged that Hekmatyar’s recent activity had been “outrageous”. They planned a “showdown” with him for allegedly stealing US funds from a French team in Afghanistan.

Pakistan’s spy chief, General Hamid Gul, began to harbour doubts about his own country’s substantial support for Hezbi Islami. He found Hekmatyar “both difficult to deal with and something of a burden.”

However, the US worried that “restricting military supplies could well be counter-productive.” Washington feared reducing arms shipments would prompt Hekmatyar’s group to “use their current stocks of weapons to raid caravans supplying arms to other groups.”

This would increase in-fighting among the mujahideen “at just the wrong moment”. US planners wanted to “preserve the maximum alliance unity [between rebel factions] until Soviet forces had withdrawn.”

Faced with Washington’s position, British diplomats limited their goal to “trying to wring an apology out of Hekmatyar” for Andy’s death. Barrington was “pretty convinced” that his killers came from Hekmatyar’s group but did not snub Hezbi Islami.

Instead he attended a press conference held by Hekmatyar’s deputy in February 1988 in Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan. There, he appears to have given the warlord the benefit of the doubt over Andy’s death and believed the killers “were not acting under instructions from the centre [i.e. Hekmatyar].”

Back in London

Throughout this affair, Hekmatyar’s group maintained an office in London. And in November 1988 – barely a year after the killing – Hekmatyar was allowed back into Britain. He saw Foreign Office staff “informally” in London.

Then in March 1989, Thatcher’s foreign secretary Geoffrey Howe met Hekmatyar in Islamabad. The mujahideen had chosen him as “foreign minister” of their “interim government”.

The only country in the world to formally recognise this self-appointed group as Afghanistan’s legitimate leadership was Saudi Arabia.

Howe’s meeting took place despite the Foreign Office having decided to “keep Hekmatyar at arm’s length.”

Polish MEP Radosław Sikorski knew Andy Skrzypkowiak in the 1980s when they both worked as journalists in Afghanistan. Sikiroski survived and went on to be Poland’s foreign and defence minister.

He said to Declassified: “Hekmatyar’s an evil man, but a significant force in Afghan politics. Diplomacy is not something you do only with friends. You do diplomacy with maniacs and mass murderers.”

However when told the UK Foreign Office had allowed Hekmatyar into Britain so soon after Andy’s murder, Sikorski was dismayed. “That doesn’t look pretty does it,” he commented. “Hekmatyar’s seriously evil. I called for people like him to be punished for what he’d done.”

TIMELINE: BRITAIN AND HEKMATYAR

1985-86 - British diplomats invite Hekmatyar to the UN in New York.

1986 - MI6 helps Hekmatyar get a UK visa. He meets Foreign Office staff in London.

1987 - Hekmatyar's group kills Andy.

1988 - Hekmatyar is allowed to visit the UK again and meets Foreign Office staff in London.

1989 - Foreign Secretary Geoffrey Howe meets Hekmatyar in Pakistan.

‘Venomously anti-British’

Days after Howe saw Hekmatyar, diplomats noted the warlord was “venomously anti-British” and “represents the worst kind of fundamentalism, as much anti-Western as anti-communist.” They added: “He is the very last person we want to see rule an independent Afghanistan.”

British diplomats felt followers of Hekmatyar had “certainly murdered” Andy. “Even if this was not done on his orders he has done nothing to bring the culprits to justice,” they said.

Despite serious misgivings about Hekmatyar, diplomats felt “by talking to him, we can try to counter his anti-British bias”. On the other hand, they worried: “By snubbing him we can only confirm it.”

So UK diplomats decided: “We cannot forget [Andy] Skrzypkowiak, but we should not allow the case to constitute a permanent bar to a dialogue with a figure of Hekmatyar’s importance.”

The Foreign Office concluded one of its most senior diplomats could meet Hekmatyar if he travelled to London in 1989. It is not clear if that visit went ahead.

Butcher of Kabul

When the mujahideen eventually captured Kabul in 1992, they offered to appoint Hekmatyar as prime minister of Afghanistan. However, he continued to fight fellow warlords and repeatedly shelled civilian areas of the country’s capital city. This earned him a reputation as the “Butcher of Kabul”.

Sikorski is critical of how close the US and UK were to Hekmatyar during the Cold War. “He was receiving more resources than people who were actually fighting the Soviets, like Massoud. Hekmatyar was always positioning himself for a takeover after the Soviet defeat.”

Sikorski added. “Massoud was busy fighting the Soviets in the Panjshir Valley and Hekmatyar travelled to the US and London.”

When the US invaded Afghanistan in 2001, Hekmatyar helped Bin Laden escape to Pakistan. He then joined terrorist attacks on NATO troops in Afghanistan and now, in his seventies, supports the new Taliban regime.

In his memoirs, Barrington defended Western support for Afghan mujahideen during the Soviet occupation.

He noted: “It is easy to say now that the Islamic extremists of today with their suicide bombings are so abhorent that it would have been better to have kept the communists in power in Kabul.”

But he said Afghan communists had conducted “extensive purges” in the 1970s and 80s that “must not be forgotten.”

An attempt was made to contact Hekmatyar via his family but there was no response. The Foreign Office declined to comment, but pointed to a scheme it launched in 2019 which claims to “hold to account those who harm journalists for doing their job.”