In October 1996, UK prime minister John Major’s chief aide, Edward Oakden, wrote to the Foreign Office for advice.

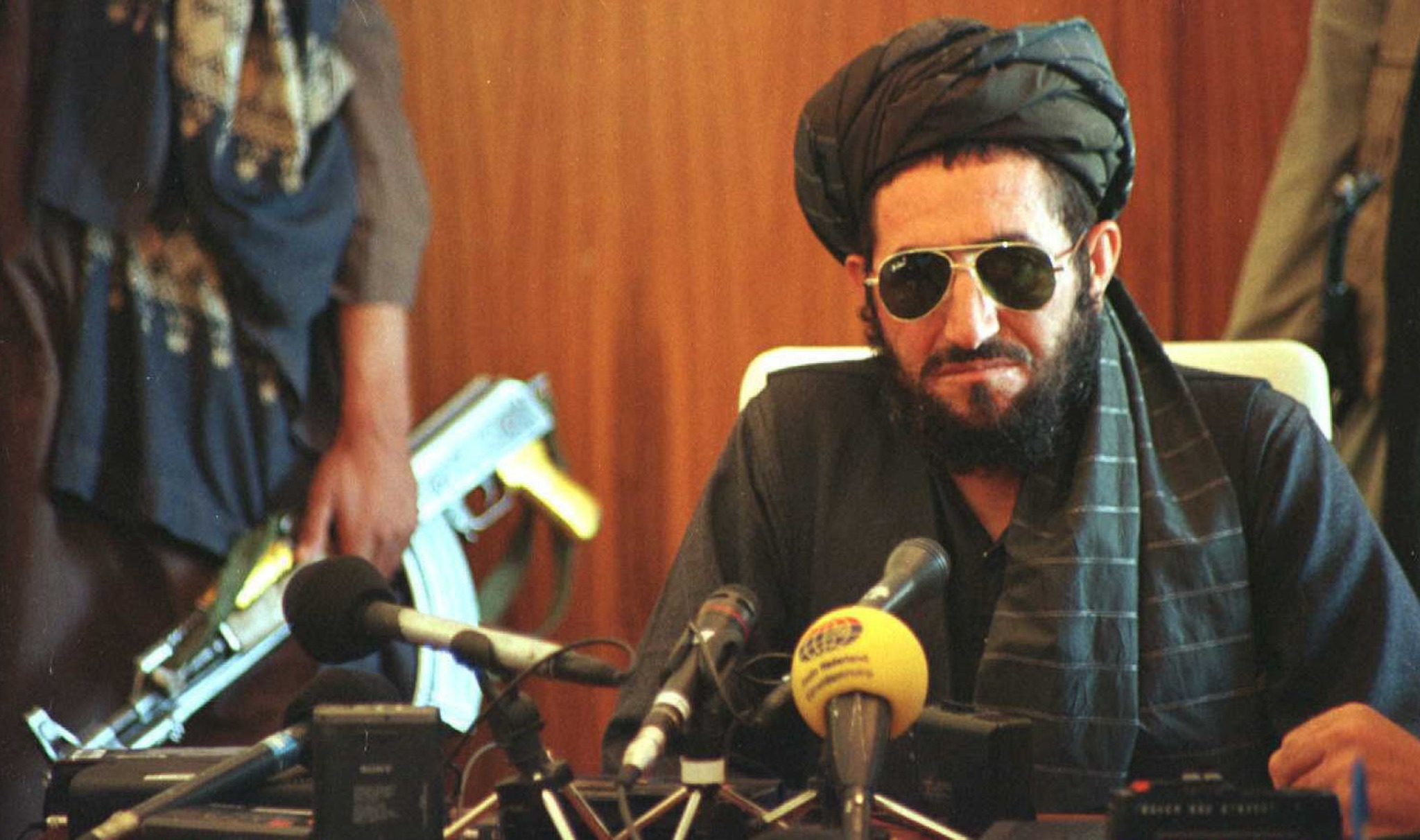

The extremist Taliban movement in Afghanistan had just seized the capital, Kabul, in the country’s brutal civil war.

Oakden asked: “How much do we know of Pakistani support for the Taliban?”

He added: “My impression is that, at least until very recently, Pakistan has been one of the Taliban’s principal suppliers/supporters”.

The question was certainly relevant. The UK and Pakistan had long been close military allies and Britain was a regular supplier of arms to the country’s military.

Two weeks later, on 8 November, Sam Sharpe, private secretary to foreign secretary Malcolm Rifkind, replied to Oakden. He began by mentioning “the widely held perception that Pakistan is the main supporter and indeed supplier of arms to the Taliban”.

Sharpe mentioned “extensive press reports” indicating Islamabad was supplying the Taliban with weapons, but noted “we do not have strong evidence to back up these reports”.

However, he concluded: “Despite the lack of evidence, we believe that Pakistan probably does provide extensive material support to the Taliban”.

“There is little doubt”, he also wrote, “that when the Taliban first emerged in late 1994, they did so from the religious schools in the Pakistani areas bordering Afghanistan”.

The UK government’s knowledge of Pakistan’s support to the Taliban reflected media reports at the time. An article in CNN noted: “The Taliban are widely alleged to be the creation of Pakistan’s military intelligence”.

The New York Times wrote in December 1996 that “Pakistan’s leaders, in funneling supplies of ammunition, fuel and food to the Taliban, hoped to advance an old Pakistani dream of linking their country, through Afghanistan, to an economic and political alliance with the Muslim states of Central Asia.”

Arms

Yet despite this knowledge of Islamabad’s involvement in Afghanistan, John Major’s Conservative government continued to approve wide-ranging arms exports to Pakistan. It surely knew those arms could reach the Taliban.

In 1997, as the Taliban consolidated its hold on Kabul and sought to capture the whole country, UK ministers authorised 93 licences for military exports to Pakistan. These included machine gun spares, ammunition components, four wheel drive vehicles, and military-use electronic equipment.

The following year, 1998, the new Labour government of Tony Blair increased the number of military goods destined for Pakistan, authorising 132 licences for export.

A range of equipment was provided including small arms ammunition, combat helmets, communications equipment, components for general purpose machine guns and night vision goggles.

Other UK military collaboration between the UK and Pakistan continued, across all three services. In 1998, 16 Pakistani military officers were being trained in Britain, the Royal Air Force had an exchange team based in Pakistan, and the Royal Navy conducted exercises with the Pakistani navy in the Indian Ocean.

Blair’s government went on to approve £190m worth of arms exports to Pakistan over its decade in office.

If Pakistan’s support for the Taliban was not sufficient to deter British support for its military, neither was Islamabad’s conduct of six nuclear weapons tests in May 1998, which followed similar tests by its regional rival, India.

Blair’s foreign secretary, Robin Cook, expressed his “dismay” to the Pakistan government over the tests and recalled the British ambassador in Islamabad for consultations, but no further serious actions were taken.

No big deal

Thousands of students of the Pakistani madrassas had crossed into Afghanistan in 1995 and 1996, advised and armed by the Pakistani army as they gradually took control of Afghanistan’s urban centres.

While the Pakistani army was nurturing the Taliban at that time, Britain was training its officers in Britain and describing the country as a “great friend”.

London never raised public objections to Pakistan’s sponsorship of these militants, and, once the Taliban had assumed power, British government statements in parliament were striking in their lack of overt condemnation of the new regime in Kabul.

“Blair’s government approved £190m worth of arms exports to Pakistan”

In October 1996, for example, the Home Office minister in the dying days of the Major government, Ann Widdecombe, was asked whether the Taliban’s capture of Kabul meant a sufficient “fundamental change” for the British government to accept more Afghan asylum seekers.

Her reply was: “We do not believe that the recent developments in Afghanistan constitute such a fundamental change in the circumstances so as to justify … declaring that the country has undergone a major upheaval.”

She added: “Afghanistan has been in a state of upheaval for a number of years. The fall of Kabul to Taliban [sic] is part of this long-term continuing conflict.”

Thus the Taliban’s assumption to power was no big deal; the Conservatives’ desire to keep out Afghan asylum seekers was deemed more important than recognising the reality of Kabul’s new rulers.

The Taliban immediately set about violently enforcing their strict Islamic code, closing girls’ schools and imposing harsh punishments such as amputations.

Bin Laden

Pakistani – and Saudi – arms and money continued to flow to the Taliban, enabling it to conquer the north of the country in the autumn of 1998. By now Osama Bin Laden was firmly ensconced in the country, having arrived in Jalalabad, eastern Afghanistan, from Sudan in May 1996, just in time to see the Taliban take Kabul.

The Al Qaeda leader was initially protected by Yunus Khales, one of the mujahideen (holy warrior) commanders covertly backed by Britain in its secret war against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s.

It is believed that both Pakistan and Saudi Arabia then struck deals with Bin Laden. Soon after his arrival Bin Laden met representatives of the Pakistani military who encouraged him to back the Taliban in return for protection by the Pakistani government.

Pakistan’s intelligence service, the ISI, then helped Bin Laden establish his headquarters in Nangarhar province and agreed to provide him with arms, a deal which was also blessed by the Saudis.

According to US intelligence reports, ISI officers at the level of colonel met Bin Laden or his representatives in the autumn of 1998 in order to coordinate access to training camps in Afghanistan for militants destined for Kashmir.

The CIA suspected that Pakistan was providing funds or equipment to Bin Laden as part of the operating agreements at these camps. Meanwhile, Bin Laden got on with the task of building up his terrorist infrastructure in Afghanistan.

The US Defence Intelligence Agency later noted in a declassified cable that “Bin Laden’s Al Qaeda network was able to expand under the safe sanctuary extended by Taliban following Pakistan directives.”

It also noted that his camp in Afghanistan was built by Pakistani contractors funded by the ISI, which was “the real host in that facility”.

The ISI is also believed to have tipped off Bin Laden about a series of US attempts on his life in the late 1990s in retaliation for the 1998 embassy bombings in East Africa.