- The UK government is leading opposition to negotiations for a new global tax convention to strengthen standards for tax transparency and cooperation

- In the UK, US, Germany and France, 90% of the population believe governments should stop companies that receive public support in the pandemic from using tax havens

In a United Nations meeting at the beginning of March, the UK delegation took to the floor to welcome a landmark report on international tax abuse and illicit finance – and proceeded to oppose its central recommendations.

Just a week later, the Corporate Tax Haven Index 2021 revealed the dominance in this dirty game of the UK and its network of dependent territories. But the international tide may have turned against illicit financial flows – and Brexit Britain now faces an important choice.

To understand the UK government’s dilemma, we need to recognise the central role of the British Empire in the three great ages of illicit financial flows of the last half a millennium.

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are cross-border transfers of funds motivated by the laundering of the proceeds of crime, by grand corruption, by the abuse of market regulations or – last and almost certainly largest – by corporate and individual tax abuse.

They have two common features. First, IFFs are, necessarily, hidden. Whether they’re actually criminal, or just socially unacceptable, IFFs depend upon financial secrecy to achieve their goal, typically through the use of anonymous legal vehicles and financial asset classes, and of jurisdictions that provide these and neither require transparency nor provide international administrative cooperation.

And second, IFFs do great damage. Across the range of motivations, they reduce the resources available to states (the funds held or the tax revenues due), and the effectiveness and legitimacy of states to use their funds for the broader benefit of the population.

States that experience significant IFFs are therefore poorer, and at the same time their governance is undermined. A pernicious narrative in recent decades has labelled lower-income countries (typically former colonies) as “corrupt”.

But the jurisdictions that facilitate IFFs overwhelmingly enjoy higher per capita incomes – and are often either Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members or their dependent territories.

Three global ages of illicit financial flows

The period of formal British and other European empires can be thought of as the first great age of IFFs. While much of the extraction inflicted on the rest of the world was the simple result of open violence, including enslavement, a significant element was hidden.

Empire relied often upon charter companies; not just the famous East India Company but many lesser-known counterparts. Direct violence was very much part of their modus operandi, but the charter companies were also legal vehicles for the private enrichment of metropolitan shareholders – including through the illegitimate control of tax-raising powers, and the unaccountable manipulation of trade prices.

The second age of IFFs coincides with the gradual end of formal empire, from the early 20th century onwards. As the “threat” of independence loomed in colonies around the world, many of the agents of empire – corporate and individual – sought to secure their illicit enrichment from the threat of expropriation.

But, by this time, fiscal pressures in the metropole had given rise to substantial direct taxation of income and profits there. The path to keeping illicit gains intact was to seek out an alternative jurisdiction through which to channel ownership – within the comfort of empire’s system of laws, but without the prospect of its effective taxation (and still less, of any reparative justice by a newly independent government).

While imperial jurisdictions with an appropriately pliable approach to law and transparency were soon rewarded by an influx of illicit gains, it was only later – in the third age of IFFs, after World War Two – that this became fully institutionalised within the international economic system.

The City of London sought to rebuild its global pre-eminence by undercutting capital controls and related regulations that applied in competitors such as New York. The UK government, meanwhile, saw internal arguments over the appropriate future for its remaining territories – many of them small island states.

On the one hand, ministers wished to be free of the need to support these territories financially. Encouraging them down the road to tax havenry, on which some had already embarked, appeared to offer an economic development path that could save the British exchequer money.

On the other hand, some warned that such a move would raise risks for UK tax revenues. The compromise, as Nicholas Shaxson details in his archival work for the book Treasure Islands, was to push this path, on condition that funds channelled through these territories were then used to bolster the City’s international position, and – broadly – to undermine the revenues of other states than the UK.

These decisions set the scene for the third age of illicit financial flows: in which “offshore” moved from the margins of the global economy to the absolute centre, with almost all major multinationals and banks regularly transacting through financial secrecy jurisdictions and the overlapping category of corporate tax havens.

The UK’s threat to the world

And so we arrive at the point today that the UK, together with its network of dependent territories, poses the biggest global threat of illicit financial flows suffered by other countries around the world.

Here’s how the Tax Justice Network measures this. Every two years, we publish the Financial Secrecy Index (FSI). This ranks countries and jurisdictions based on a combination of 20 indicators of law, regulation and practice that are merged to give an overall secrecy score, with a measure of their share of global finance.

Together, this allows us to measure the relative risk that each jurisdiction poses to the rest of the world, through their provision of financial secrecy that facilitates illicit financial flows.

Every other year, we publish the Corporate Tax Haven Index (CTHI). This is constructed in a similar way to the FSI, and provides a measure of the relative risk posed by each jurisdiction in terms of the profit shifting by multinational companies that others suffer.

Finally, our new, annual State of Tax Justice report provides leading estimates of the revenue losses suffered by each country due to individual offshore tax evasion, and due to corporate profit shifting; and the revenue losses that each country imposes on others by facilitating the underlying tax abuses.

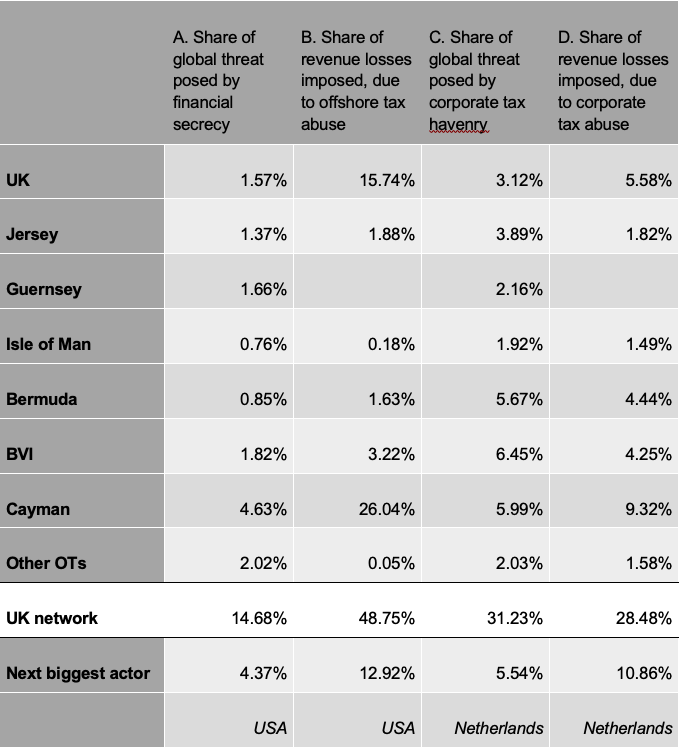

That provides four measures of contributions to illicit financial flows, as shown in the table/figure. On every single one of those measures, the UK and its network of dependent territories is – by a distance – the biggest global threat.

Overall, the UK and its network are responsible for around 15% of financial secrecy risks, and almost twice that share of profit shifting risks.

Or more concretely, some $160-billion of tax losses around the world each year: more than one-third of the global revenue losses due to cross-border tax abuse by companies and individuals.

A global tide turning?

The world just might be witnessing the beginning of the end of this third age of illicit financial flows.

The UN High-Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity (the FACTI panel) was launched in March 2020. Its final report, launched by a group of heads of state and ministers from around the world, may come to be seen as a pivotal moment in the world’s fight against illicit finance and tax abuse.

Reflecting a year of detailed analysis and engagement with UN member states in every global region, the report calls for powerful, specific policies to be implemented, in respect of both tax transparency and international tax rules.

The report also envisages sweeping reforms to the global architecture – and it is here that the conflict really begins. For decades, international tax rules have been set largely by the OECD: the group of rich countries.

The consensus of the economic research is that OECD countries lose the most – hundreds of billions of dollars in foregone revenue – from the failure to tackle profit shifting by multinational companies.

The populations of many OECD countries have expressed a clear preference for such tax abuses to be ended. In the UK, as in the US, Germany, France and other countries, some 90% of people polled last year said that their governments should stop companies that receive public support in the pandemic using tax havens.

But if OECD countries have failed their own citizens by leaving these tax abuses unhindered, it is lower-income countries – largely excluded from voice or influence in the setting of OECD rules – that lose the most as a share of their actual tax revenues.

This group includes the countries with the smallest budgets for national health and other public services, and so the losses due to tax abuse transform much more starkly into human costs.

This is the central conflict behind international corporate tax rules. Should the rules be set by negotiations between all countries, as happens for example with international trade or climate change?

Or should tax remain an anomaly, with the rich countries of the OECD wielding disproportionate power?

The UN FACTI panel provides a decisive answer. The final report calls for the negotiation of a UN tax convention. This would set new standards for transparency and cooperation, ensuring countries at all income levels are fully included, and create a truly global, intergovernmental tax body to take over rule-setting from the OECD.

Since the end of the Trump administration, it is the UK that has led opposition to these proposals, with the support of Switzerland.

The aim, presumably, is to maintain the disproportionate power of OECD countries to set tax rules that don’t work even for them, and are even more harmful for lower-income countries. To many of which the UK is now cutting aid, because of concerns over its own revenues.

Documents seen by OpenDemocracy suggest, with inglorious irony, that the axe will fall hardest on aid that supported the country’s “anti-corruption” efforts.

And so this is the “global Britain” on show to the world at the United Nations: heading up the world’s biggest tax haven network, and using its diplomatic power to lead the fight against effective reform.

Nationally, it is surely time for the UK to have a public debate on the role the country wishes to play. But internationally, the UK is now out of the European Union’s somewhat restraining influence.

Is it time for concerted action against the biggest global pusher of illicit financial flows?