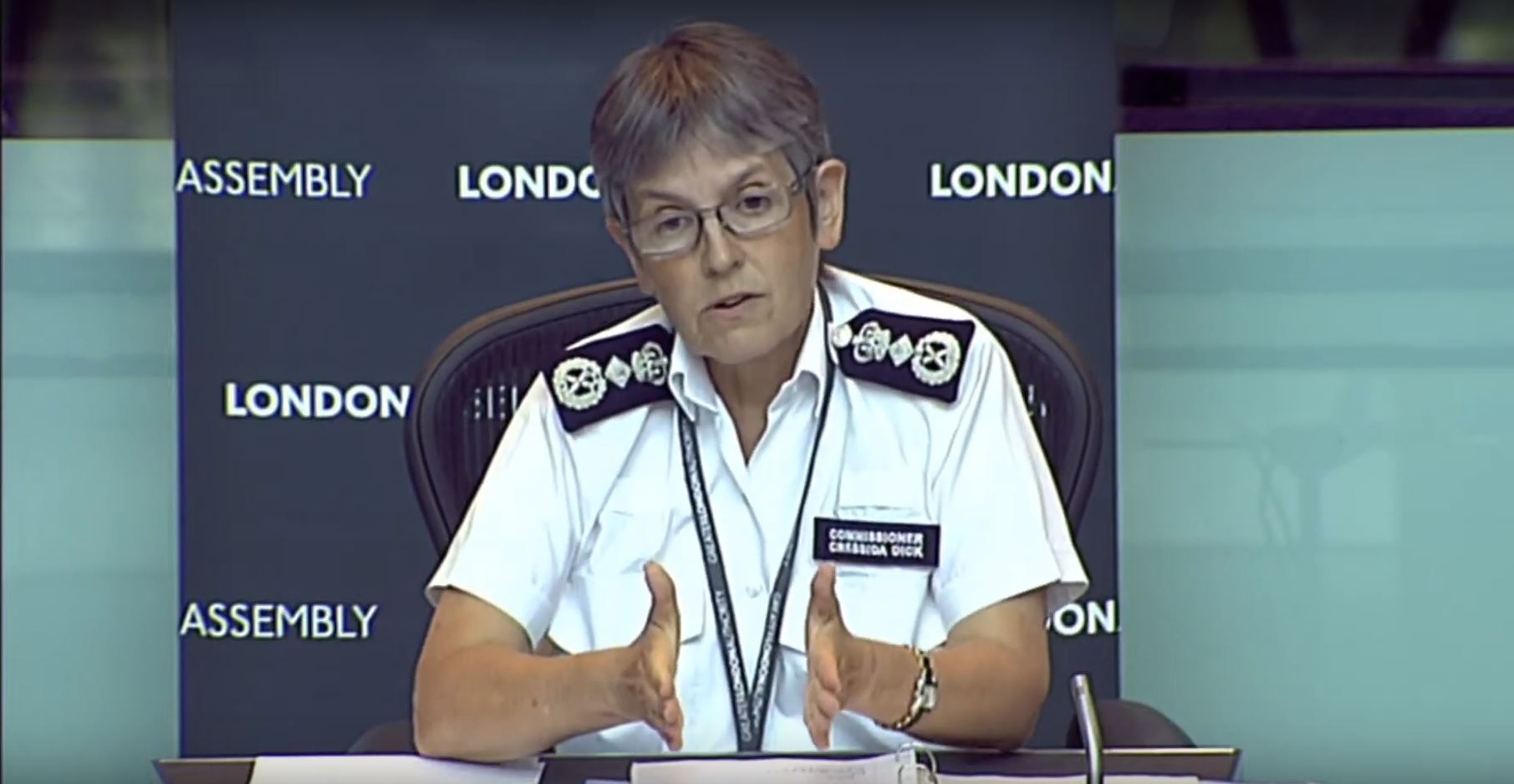

There is something very curious about Cressida Dick, something that has protected her, Teflon-like, from criticism and allowed her to survive intact without having to come down to Earth and explain herself fully to men and women on the street, that is to say the public.

The first female and openly gay Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Britain’s most senior police officer, has been able to avoid public scrutiny throughout her illustrious — but at times mysterious — career.

Dick first came to notice while embroiled in controversy in July 2005 soon after the 7/7 London bombings. She was then “gold commander” in charge of the combined police and army special forces operation that led to the fatal shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes in south London.

The Brazilian was wrongly identified as a suicide bomber. An inquest returned an open verdict rejecting the police account that he was lawfully killed.

At an earlier trial, an Old Bailey jury said that while Dick bore “no personal culpability” the Met was guilty of endangering the public and of breaking health and safety rules when it pursued Menezes at Stockwell underground station and shot him seven times.

The Met was fined £175,000 with £385,000 costs. The jury heard that Scotland Yard commanders had made a number of errors in the confusion that led to the killing of Menezes.

Clare Montgomery QC, prosecuting, said the situation had worsened because senior officers failed to keep to their own agreed plan, while firearms teams were poorly briefed and in the wrong locations.

Role with MI6

In 2011, Dick was appointed deputy commissioner in charge of the Met’s counter-terrorist activities in which she had been involved for many years. It was a job she is reported to have revelled in and included security surrounding the 2012 London Olympics.

In 2014, however, the Met commissioner, Bernard Hogan-Howe, removed her to a post in charge of “specialist crime”. Why he did so is unclear.

Ousted from a job she liked so much, she found — or was offered — a sanctuary in the secret world of spooks. It was said she had joined the “Foreign Office” in an unexplained role.

She was appointed to a senior job understood to be in Britain’s foreign intelligence service, MI6, a position she held until appointed to head the Met in 2017.

Her role in intelligence is shrouded in mystery.

The Foreign Office, whose ministers are MI6’s political masters, said only that her new job “related to security”, and it therefore could not comment further.

When one journalist made Freedom of Information Act requests concerning her position, the Foreign Office repeatedly refused to disclose even the most basic details, such as her job title and salary.

It was most strange that her post was not officially gazetted and that her new role was not questioned.

Dick was installed in MI6 at precisely the time the agency, including its head of counter-terrorism, Sir Mark Allen, was being investigated by her former colleagues in Scotland Yard. She would have certainly known about the investigation.

The case concerned MI6 collusion in the abduction of terror suspects Abdel Hakim Belhaj and Sami al-Saadi, who were subsequently tortured by Libyan secret police under its dictator, Muammar Gaddafi.

In January 2012, after MI6’s role in the renditions came to light, the Met issued a statement. It said the allegations against MI6 were “so serious that it is in the public interest for them to be investigated now”.

The Met subsequently handed the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) a dossier of nearly 30,000 pages. More than four years later, in 2016, the CPS issued a convoluted statement clearly reflecting its discomfort.

It said that Allen had “sought political authority for some of his actions albeit not within a formal written process nor in detail”.

After stressing it had obtained information from a large number of MI6 and MI5 records, the CPS concluded there was “sufficient evidence to support the contention that the suspect [Allen]… had been in communication with individuals from foreign countries responsible for the detention” of the two Libyans and their families and “sought political authority for some of his actions”.

The CPS added that British officials did not themselves “physically detain, transfer or ill-treat” the two Libyans, and it was “impossible to reconcile conflicting evidence about what happened at the time… or to prove each element of the offences to the required criminal standard”.

It was a carefully crafted let-off. No one has been prosecuted over the case.

Theresa May, then prime minister, prevented MI6 officers from giving evidence to Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee’s inquiry into British collusion in the rendition operations.

Shortly afterwards, however, the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, seemed to suggest the police did indeed have sufficient evidence to mount a prosecution. The Met, he said, had submitted “a comprehensive file of evidence” to the CPS “seeking to demonstrate that the conduct of a British official amounted to misconduct in public office”.

The CPS decision not to bring any charges was reported to have dismayed Scotland Yard officers involved in the investigation.

Eliza Manningham-Buller, the head of the security service MI5, was so incensed about the activities of MI6 officers that she banned them from conducting joint counter-terrorism operations in MI5’s London headquarters, Thames House.

Manningham-Buller was concerned that MI6’s collusion with the CIA and Gaddafi’s intelligence agents in operations would compromise the safety of MI5 officers, intelligence-gathering operations and informants.

She was particularly concerned by MI6’s collusion in operations that involved torture and the potential impact on the work and reputation of all British counter-terrorist agencies, MI5 as well as MI6.

“Institutional corruption”

More recently Dick was criticised in the wake of the death of Sarah Everard after police officers were accused of oppressive mishandling of a vigil held in her memory and to protest against men’s violence against women.

Early last month, on the day one of her officers pleaded guilty to Everard’s kidnapping and rape while she was walking to her home in Brixton, south London, Dick told the Women’s Institute: “I have 44,000 people working in the Met. Sadly, some of them are abused at home, for example, and sadly, on occasion, I have a bad ’un”.

Though Dick said the Met was angry and shocked by Everard’s death, her apparent description of Everard’s attacker seemed inappropriate and almost offhand, to this writer at least.

A week later, a scathing report was published by an independent inquiry into the murder of Daniel Morgan, a private investigator found dead in 1987 in a south London pub car park with an axe in his head.

It accused the Met of “a form of institutional corruption”, accusing Dick’s force of hampering its efforts to get to the truth.

Baroness Nuala O’Loan, who led the inquiry said: “At times our contact with the Met resembled police contact with litigants rather than with a body established by the Home Secretary to enquire into a case”.

She added: “The Metropolitan Police placed the reputation of the organisation above the need for accountability and transparency”, compounding the Morgan family’s “suffering and trauma”.

The inquiry criticised senior officers in the Met for lack of candour and supervision. It said Dick, then an assistant Met commissioner initially involved in the investigation, refused to grant access to a police internal data system and the most sensitive information surrounding the case.

The National Police Chiefs Council lead for counter-corruption, Chief Constable Stephen Watson, said: “This is a very serious accusation that the Metropolitan police will need to consider carefully and respond to fully, which they have said they will do.”

Private Eye magazine pointed out that Boris Johnson, when he was mayor of London in 2014, agreed to pay the Morgan family £50,000 in recognition of “the general social benefit brought about by their efforts in bringing to light the failings of the Met”.

After the O’Loan report was published he insisted Dick retained his full confidence.

Dick has said that it was a “matter of great regret that no one has been brought to justice and that our mistakes have compounded the pain suffered by Daniel’s family”. But she added: “I don’t accept that we are institutionally corrupt, no.”

She denied she had obstructed the work of the inquiry. “I set out with my team, who were well-resourced, to ensure that we gave the panel maximum cooperation, and that we did full disclosure, as quickly as we could”, Dick said, insisting she acted with integrity.

In a career not short of controversy, Dick has vigorously denied charges that the Met is institutionally corrupt or institutionally racist. But one matter she has not commented on is what she was up to with MI6.

We surely have a right to know, especially given that at the time the Met was investigating her new hosts.

Declassified asked the Metropolitan Police if Dick could provide details about her role with MI6. It told us: “The Commissioner Cressida Dick left policing in 2015. She joined the Foreign and Commonwealth Office until her selection as the Commissioner of the Met Police was announced. She was re-attested as a police officer in April 2017.”