“Iran is an autocracy and all power flows from the Shah”, the British Ministry of Defence (MOD) wrote in an internal file of April 1975. At the time, the UK had an array of military training teams in Iran and a contract to sell its ruler, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, over 1,500 tanks.

Before the 1979 Islamic revolution swept the Shah’s power away, his extremely repressive regime had been one of Britain’s closest allies in the Middle East for a quarter of a century.

It is something many Iranians, now demonstrating against another autocratic regime in Tehran, have never forgotten.

British ambassador Peter Ramsbotham recognised in 1973 that the Shah was “effectively a dictator”. The year before, he told London that Iran’s ruler was “becoming increasingly autocratic… and every year the Shah is taking more power into his own hands”.

The Foreign Office was so aware of the true nature of their client that one senior official thought the Shah “may be moving towards megalomania”.

None of this mattered. The UK supported the Shah’s army precisely since it was an “instrument of that power”. “By our standards”, the MOD noted, the Iranian army “is essentially feudal in both its loyalties and attitudes”. “The word of the Shah is gospel”, it stated.

Iran under the Shah had the advantage of being Britain’s biggest customer for arms exports in the world. Not only tanks, but destroyers, support ships, armoured vehicles and ammunition were also supplied.

“The benefits to the United Kingdom of our arms sales to Iran are enormous and we must continue to reap them”, Ramsbotham’s successor, Anthony Parsons, noted.

Whitehall promoted the very survival of the dictator. The Imperial Guard of the Iranian army, which was responsible directly to the Shah, had a battalion of the Chieftain tanks Britain had supplied to the country.

The UK’s Commissioning and Advisory Team (CAAT) – as the military training team was known – was even based in the same building in Lavizan, in northeast Tehran, as the headquarters of the Iranian army.

Other services were also there. An RAF wing commander was attached to the Iranian air force “to give ground to air advice” and there was also a small Royal Marines advisory team assisting Iran’s navy “in the formation of a Marine Commando”.

Bribery

Britain’s MI6, working with the CIA, had in 1953 put the Shah in power in a coup overthrowing the country democratically-elected leader Mohammed Mossadeq. The UK and US proceeded to prop up the Shah’s repressive rule however draconian it became.

The government of Edward Heath agreed a major sale of tanks to Iran in 1970 and the following year dispatched a military training team to service and maintain them.

These services were performed mainly by hundreds of staff working for a military company, Millbank Technical Services, and were managed by a retired British Brigadier. MTS was a subsidiary of a state body, the Crown Agents and was later owned and run by the MOD as International Military Services Ltd.

“It has long been reported that MTS acted as a UK government vehicle to pay bribes to Iranians receiving UK arms”

It has long been reported that MTS acted as a UK government vehicle to pay bribes to Iranians receiving UK arms without the direct involvement of Whitehall.

The Guardian reported: “MTS would buy the tanks from the MoD in a paper transaction. MTS would also dispatch the secret cash to the Shah. MTS would then ship the tanks to the Iranian army, and present an inflated bill for tanks plus bribes”.

“The trickery of the MTS scheme”, the Guardian noted, “was approved in Britain at the highest level”.

Political prisoners

The Shah and his wife visited the UK in June 1972. “They came as guests of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor the Royal Ascot races”, Peter Ramsbotham noted.

He also wrote, in his annual review for Foreign Office, that there was “growing discontent throughout the country”. This came not least since the Shah’s “personal and detailed control over every facet of the Administration and economy is proving to be inhibiting, not only to political party activity but also to the sense of responsibility of his ministers, senior civil servants and other leaders in the country”.

By 1974, the UK documents contained a report from Newsweek noting there were 50,000 political prisoners in Iran. Somewhere between 30,000-60,000 people worked for the notoriously brutal and feared internal security service, SAVAK. Amnesty International and others documented numerous cases of torture.

SAVAK was “extremely efficient and certainly as brutal as any secret police in the area”

Nick Browne, an official in the British embassy in Tehran, anonymously told one media outlet that SAVAK was “extremely efficient and certainly as brutal as any secret police in the area”.

None of this affected British policy, except to deepen Whitehall’s backing of the regime.

Patrick Wright of the Foreign Office’s Middle East Department wrote in July 1974 that “Iran is as a good a bet for British interests as most countries and I agree that the longer the Shah lasts the better the chances of a peaceful succession and even, with a little bit of luck, that there is still a good chance of a strong and basically pro-Western government in the event of his premature disappearance”.

The Foreign Office summed up its view in September 1975, in a brief for foreign secretary James Callaghan: “We consider that Iran is an important factor for stability in this area which produces over 70 per cent of our oil imports and the Shah sees us a counterweight to Russian influence in the region… Iran is a major overseas customer for British defence equipment.”

Keeping the security service happy

Britain’s support to the Shah included backing in the propaganda field stretching back to the early 1960s.

The UK’s infamous Information Research Department (IRD), its cold war propaganda unit, played various roles in bolstering the Shah’s ability to fend off internal threats, whether from the pro-Soviet Tudeh party or from Arab nationalists supportive of Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser.

The IRD provided material for “unattributable use by the press and radio” directly to SAVAK. This included spending on “book translation, articles for the press and counter-subversive propaganda work of various kinds”, IRD official Ann Elwell wrote in December 1964.

“We are particularly keen to get ideas for the sort of themes and arguments which would be effective locally”, Assistant Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs Leslie Glass wrote, adding that the UK’s cooperation with SAVAK was “satisfactory and effective”.

A few months earlier Elwell had promoted a visit to the UK by a senior SAVAK official, a Dr Zehtab, at the request of the director of the agency, General Hassan Pakravan.

It was “important to us to keep the Iranian Security Service happy”

“In our embassy in Tehran the Assistant Information Officer is responsible for doing IRD work in consultation with one of General Pakravan’s deputies, Dr Zehtab, who spent ten days in the UK at IRD’s expense in October this year and was shown a great deal of IRD’s activities”, Elwell wrote.

She noted that Pakravan was “anxious for Dr Zehtab to learn more about our unattributable publicity activities”. Elwell wrote that the IRD was helping the Shah’s regime “with their own public relations work”.

She added that it was “important to us to keep the Iranian Security Service happy”.

“There is no doubt that the visit was a success and that Zehtab obtained real benefit… from it. He speaks with great enthusiasm of the work being done by IRD”, Elwell noted. The files indicate visits were arranged to the BBC and St Anthony’s College Oxford as well as the IRD.

Whitehall provided another favour for SAVAK. An official in Tehran, Michael Elliott, informed Elwell that SAVAK had asked the embassy “if we can supply the names of some firms in London which would undertake the task of publicising the Iranian image abroad, with a little tourist promotion work as a sideline”.

Elliott suggested this be taken forward and that Iran could pay up to £50,000 a month.

Elwell replied saying this had been discussed with Colman Prentis & Varley, “one of the biggest UK advertising agencies”. She noted: “As part of the package they could offer sponsored visits by travel writers, a campaign among travel agents, special invitations to TV and radio reporting groups etc.”

Apologising for torture

Whitehall officials tried to bury in public what they knew in private. In December 1972, for example, the Iranian embassy in London complained to the Foreign Office about a recently published book – A Visit to Iran – written by one of its officials, Elisabeth Sharpe.

“The book contains frequent allegations of corruption, persecution and torture in Iran and includes disobliging references to the Shah”, an official wrote, surely echoing what every British official knew about the regime.

Whitehall decided to apologise. “The Head of the Middle East Department has formally expressed regret to the Iranian Minister/Counsellor and has assured him that the views in the book in no way reflect HMG’s views of Iran”, a document notes.

He also “recommended that a personal letter of regret should go from the PUS [permanent under-secretary] to the Iranian Ambassador since the book, and our reactions to it, will without doubt be conveyed to the Shah.”

The Foreign Office also suggested to then minister Lord Balniel, for his upcoming talk with the Iranian ambassador in London: “The Minister of State may wish to state that he is aware of the matter and hopes that this unfortunate publication will not be allowed to mar the excellent relations which exist between our two countries”.

Revolutionary government

Some UK officials recognised there might be a problem supplying so many arms to a regime that might one day fall. “All this equipment could be in the hands of a revolutionary government”, a diplomat in the Middle East Department wrote in 1972.

This didn’t matter either. Towards the end of the decade, the UK had in place arms sales to Iran worth over £1bn. No less than 1,200 tanks were due to be exported to the Shah from 1978-82 under Project 4030, as it was known.

Now prime minister James Callaghan wrote to US president Jimmy Carter in December 1978 saying that the removal of the Shah would have “the gravest political, strategic and economic implications for the West”.

“Whatever his faults, it was still in our interests that the Shah should remain in power”

As opposition to the Shah grew in Iran and demonstrations became larger, Whitehall clung on its dictator until nearly the very end. “Whatever his faults, it was still in our interests that the Shah should remain in power”, foreign secretary David Owen told the Cabinet on 9 November 1978 – a few weeks before the Shah fled.

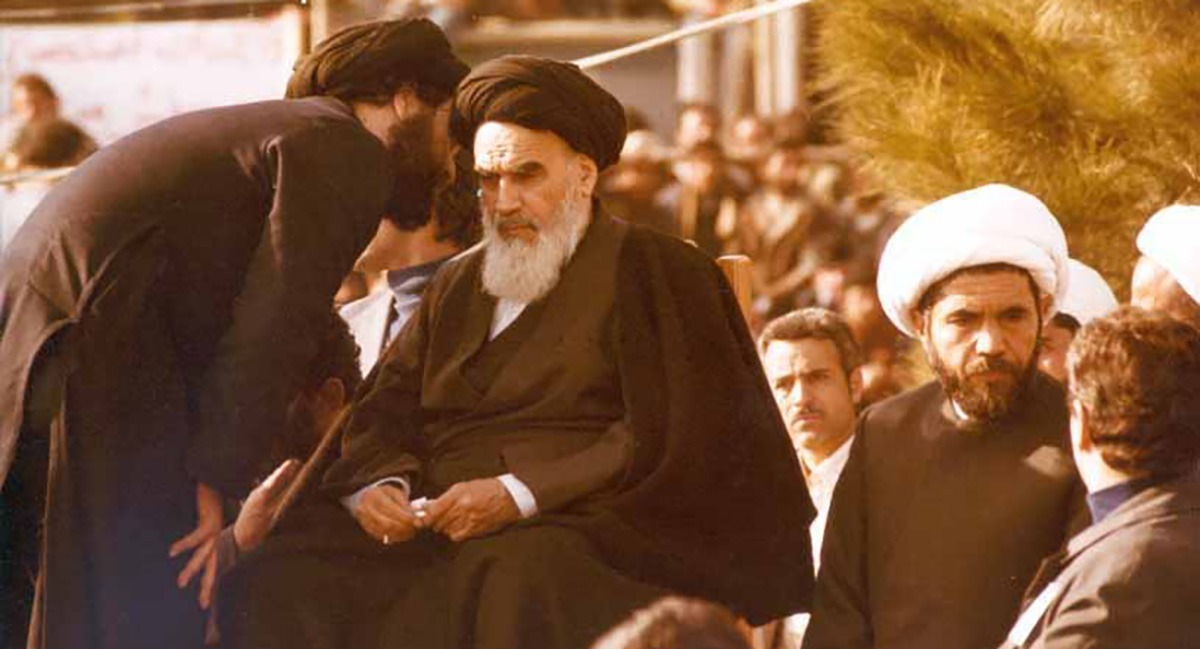

Owen added: “A military government without him would be no improvement and a government under the anti-British Ayatollah Khomeini would be far worse”.

When the Shah asked for internal security equipment from the UK after protests in August and September, Britain obliged. In November 1978, David Owen approved the sale of 175,000 CS gas cartridges and up to 360 unarmed armoured personnel carriers.

‘Nationalist policy’

A Cabinet paper of November 1978, entitled ‘The political future for Iran’, expressed British fears about a possible Islamic republic. It noted that “while some of its social policies might be reactionary, in economic and foreign affairs it will likely pursue a radical and nationalist policy”.

“Such a government”, it added, “would seek to dispense with foreign advice and that of the business community” while in “in foreign policy, an Islamic republic would probably be neutralist”.

Parsons, the British ambassador to Tehran, privately invited Richard Clutterbuck – “the leading UK expert” on counter-insurgency – to Iran “in the last throes of the Shah’s regime and found him an excellent adviser”. It remains unclear what Clutterbuck advised on.

It was only when Owen recognised that the Shah was in a “hopeless” position, in December 1978, that he and the Foreign Office decided to accept the Shah’s fall. The dictator fled Tehran on 16 January 1979, and on 1 February Khomeini returned from exile to Iran.

Now, the British tried to ‘insure’ themselves with the new Islamic regime by avoiding any association with the Shah. Along with the Americans, London refused to allow its onetime placeman political asylum in Britain.

“There was no honour in my decision”, Owen noted in his autobiography, “just the cold calculation of national interest”, adding that he considered it “a despicable act”.

Iran’s new regime, meanwhile, repudiated the contracts for the British tanks. Since the Shah’s Iran had already paid for some of them, it led to a decades-long attempt by Tehran to get its money back.

It was this British debt that led to the detention in Iran of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who has only just been released.