Twenty five years ago today NATO bombed Montenegro’s main airport.

It came amid airstrikes on Yugoslav forces in Kosovo, where Bill Clinton and Tony Blair waged a “humanitarian intervention” ostensibly to save ethnic Albanians from Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic.

Yet a 61-year-old woman, Paska Juncaj, was killed in the strikes on Montenegro’s capital Podgorica, which lasted for 24 hours.

“Shrapnel hit her in the head while she was on the way to an air raid shelter with her son,” a hospital official told Reuters.

Three others were injured – one seriously – and two houses destroyed after a cluster bomb missed its target.

Bombing Montenegro at all was controversial, because the country was friendly to NATO.

And although it remained in Yugoslavia with Serbia, its president Milo Djukanovic was anti-Milosevic and took a neutral stance on Kosovo.

The country would eventually join NATO as a member in 2017.

Approving air strikes

The Atlantic alliance did not specify which of its members had taken part in the air strikes on Montenegro at the time.

Such secrecy would become a common feature of future NATO air wars, making it hard for victims to hold individual states responsible.

But a formerly classified document reveals that Britain was heavily involved in the attack on Montenegro.

Blair’s defence secretary, George Robertson, believed an attack on Podgorica’s airport was justified because “it was being used as a base for operations in and over Kosovo” by Yugoslav jets and helicopters.

John Sawers, Blair’s foreign affairs adviser and future head of MI6, gave clearance for “precision guided munitions” to be dropped at 4 points of the airfield, which had both civilian and military functions.

“The risk of casualties was low, for both civilian and military, and of collateral damage, medium”, Robertson’s private secretary Christopher Deverell noted in a memo to Downing Street marked, “Secret – Personal” and “Limited distribution”.

On the same day, a Cabinet Office meeting of legal advisors recorded “some concern about the acceptability of explanations that have been given by NATO and national spokesmen for attacks by non-UK NATO forces on certain targets which were on the face of it civilian in character.”

Sawers concluded: “I think it would be right to continue to plan on the assumption that the Prime Minister is almost certain to agree to targets where collateral damage is assessed as high but civilian casualties remain low.”

The file has since been declassified and was passed to the National Archives in London this December.

The MoD, NATO and Lord Robertson did not respond to requests for comment.

Culture of impunity

Dr Iain Overton from campaign group Action on Armed Violence told Declassified: “The lack of transparency displayed by the Ministry of Defence over its air strikes is long and concerning. They repeatedly deny civilian harm even in the face of detailed evidence. This revelation just adds to the proof that this culture of opacity and impunity prevails at the highest level.”

It is unclear whether Britain had any involvement in another NATO attack on Montenegro the following day – 30 April 1999 – when a bridge in the village of Murino was struck by ten missiles.

Six civilians died in that airstrike, including three children, sparking a long running campaign for justice.

British aircraft did participate in the wider bombing of Serbia and Kosovo. The 78-day campaign by NATO left around 500 civilians dead, according to Human Rights Watch.

Milosovic was later overthrown and died while on trial at The Hague. Blair’s ally in the conflict, Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) leader Hashem Thaci, is currently on trial for war crimes.

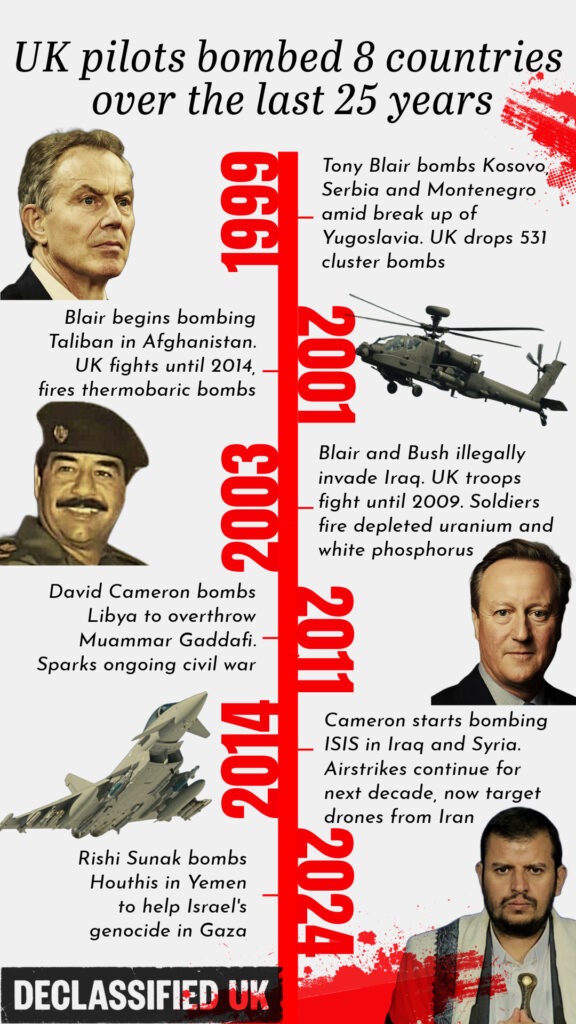

Over the next 25 years, Britain conducted airstrikes in eight countries, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen.

The list does not include military interventions like in Sierra Leone, as they did not feature aerial bombardments.

This month the RAF flew missions to protect Israel from Iranian drones.

‘My enemy’s enemy’

Britain’s military intervention in Kosovo produced mixed results. Although it allowed the return of ethnic Albanian refugees, it sparked reprisals against ethnic Serbs and empowered the KLA.

During the air war, Sawers pushed for Britain to deepen ties with the KLA, who were fighting Serb forces on the ground.

Sawers said Britain risked being “too sniffy” towards the KLA and that: “Our starting point in a conflict like this should be that your enemy’s enemy is your friend. We can sort out our differences later.”

Sawers also suggested a “minimalist interpretation” of the UN arms embargo. Blair replied: “I agree”. The KLA had easy access to small arms from their bases in Albania, where the collapse of pyramid schemes had left the state in tatters.

The file gives an important insight into the mindset of Sawers, who went on to run MI6 a decade on from the Kosovo war. In 2011 he oversaw a similar strategy in Libya where British intelligence sided with banned terrorist groups to topple Muammar Gaddafi.

Narco-state

In both cases, the Machiavellian policies have left a troubled legacy. Kosovo became virtually a narco-state on the edge of Europe, while Al Qaeda spin off groups like ISIS flourished in Libya’s power vacuum and spread terrorism to the UK.

A memo on the KLA written by a Whitehall staffer in 1999 noted it “does contain unsavoury elements…Links to drugs/crime.”

It added that the UK “do not support their goal (independence) or methods,” although Britain would be the first country to recognise Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence from Serbia in 2008.

The MoD and Foreign Office warned: “Not all the Kosovo Albanians support the KLA. And the KLA is prone to feuding, and not incapable of atrocities itself. NATO cannot be seen to be in alliance with them…KLA rule might not be a liberal experience.”

Another document warned they were “not much better than the Serbs”.

Two months after Milosevic agreed to pull his forces out of Kosovo, leaving Thaci in control, the Independent reported “around 30 people a week are being killed in Kosovo as organised gangs take advantage of the UN’s failure to police the province.”

A NATO spokesman admitted there was a “law and order vacuum” with Western diplomats saying “gangs, some of which are suspected of having links to the Kosovo Liberation Army, are taking apartments, real estate, businesses, fuel supplies and cars from Kosovo Albanians and Serbs, who have little recourse to justice.”

A declassified British government file written shortly after the war said a senior KLA veteran was “up to his neck in smuggling and organised crime”. Kosovo was described in the media as a “smugglers’ paradise” and “the Colombia of Europe”, supplying up to 40% of heroin on the continent.

Sex trafficking and forced prostitution also rose in post-war Kosovo as gangs supplied NATO peacekeepers with “hundreds of women, many of them under-age girls”, Amnesty International warned in 2004.

Organised crime

Thaci became Kosovo’s first prime minister, despite NATO believing he was among the country’s “biggest fish” in organised crime.

An investigation by the Council of Europe accused Thaci of organ harvesting, with his inner circle allegedly murdering Serb captives to sell their kidneys on the black market.

It also cited reports from anti-narcotic agencies who identified Thaci as having “violent control over the trade in heroin”.

Kosovar gangs often have close familial links with the wider Albanian mafia. The National Crime Agency said in 2017 that “Albanian crime groups have established a high profile influence within UK organised crime, and have considerable control across the UK drug trafficking market, particularly cocaine.”

Drug deaths in Britain have now reached a 30-year high, with almost 5,000 fatalities in 2022.

After decades of impunity, Thaci is now on trial for 10 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity relating to the KLA.

The degree of corruption and intimidation is so high in Kosovo that his trial has to be held at a special court in The Hague.

Tougher rules on prison visits had to be implemented in December after prosecutors complained that visitors tried to compel “witnesses to withdraw or modify their testimony in a manner favorable” to the defendants.

Thaci denies all the charges against him.