It was the evening rush hour in Dublin when three car bombs ripped through the streets of Ireland’s capital.

Ninety minutes later, a fourth device exploded in Monaghan, a town near the border with British-controlled Northern Ireland.

Those blasts on 17 May 1974 killed an unborn child and 33 civilians. Nearly 300 people were injured.

This was the deadliest terrorist attack in the bloody history of the Troubles, that long conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the British state about which much remains classified nearly half a century later.

No one has ever been charged with the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, but the shadowy Ulster Volunteer Force did eventually claim responsibility.

They are a pro-British “loyalist” paramilitary gang which fought the IRA (and innocent Irish civilians) often in collusion with the UK authorities — who even lifted a terror ban on the group six days after the blasts.

A subsequent inquiry by former Irish Supreme Court judge Henry Barron concluded: “A number of those suspected for the bombings were reliably said to have had relationships with British Intelligence and/or Royal Ulster Constabulary special branch officers.”

Barron criticised the British authorities for refusing to share key documents with his inquiry.

Battle for the truth

The Royal Ulster Constabulary has since reformed as the Police Service of Northern Ireland and today I challenged its Chief Constable Simon Byrne in court.

More than four years ago, I asked his officers to release a report into police Special Branch tactics compiled the summer before the 1974 blasts, which could shed light on those “relationships” between police and terrorists.

My freedom of information request was quickly refused. I then complained to the Information Commissioner, Elizabeth Denham, the supposed guardian of the public’s right to know, who sat on it for 18 months until it became one of her top-10 oldest files.

She finally rejected my complaint without even looking at the special branch report.

Denham sided with the police because they gave her “verbal assurances” that the report was “supplied directly” by MI5, Britain’s domestic spy agency which is completely exempt from the Freedom of Information Act under a draconian clause called Section 23.

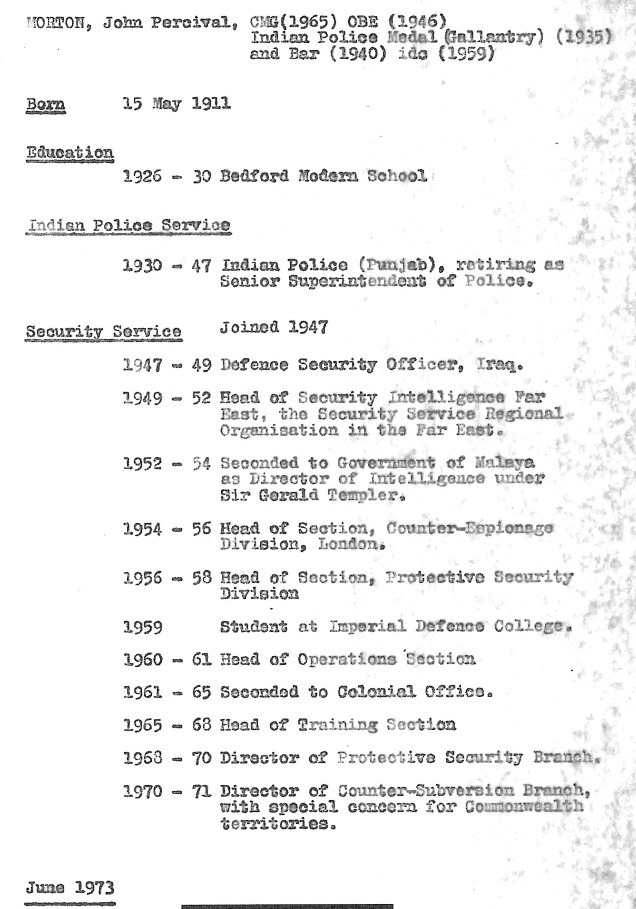

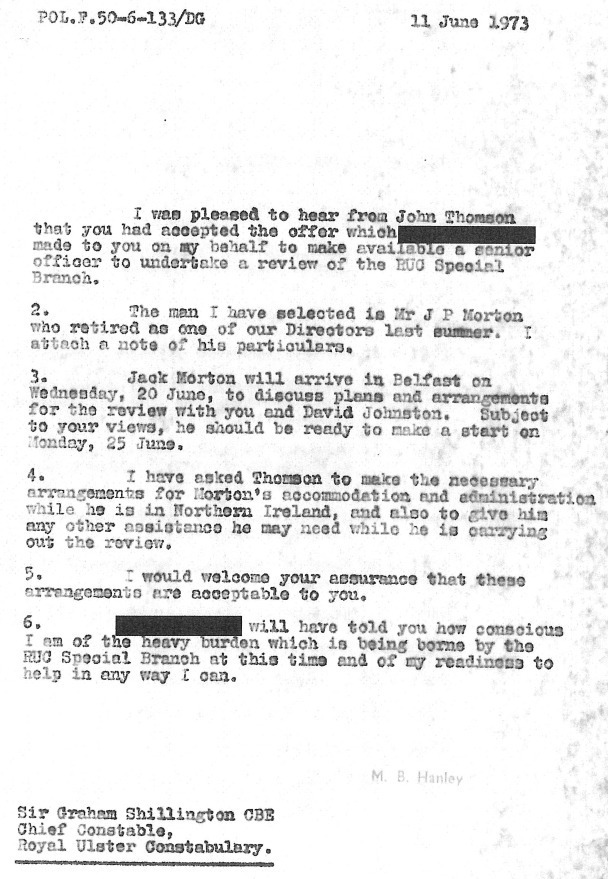

All she would say is that in June 1973 Northern Ireland’s police chief allowed a “senior MI5 officer to conduct a review of and report on the RUC Special Branch organisation and its functions”. The man who carried out this task was Jack Morton, “a serving MI5 officer”.

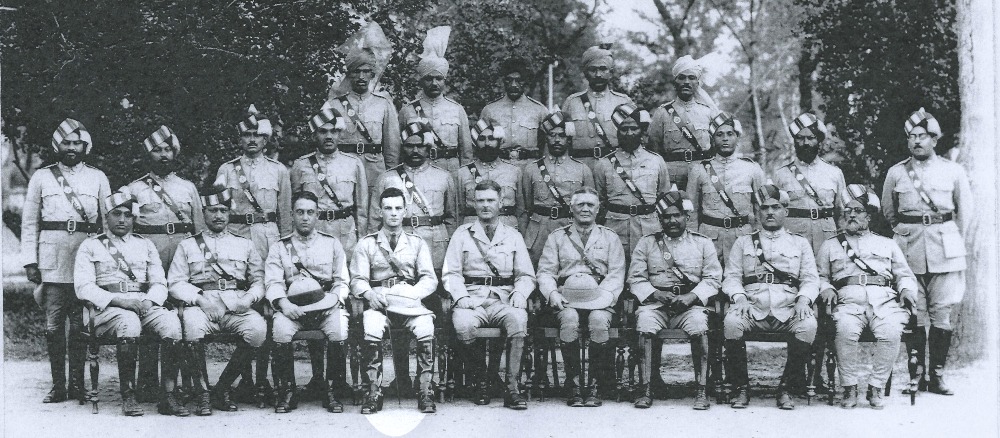

Morton was a veteran of imperial policing in the Punjab who believed that “Indians were a sort of immature, backward and needy people whom it was the natural British function to govern and administer.” He had honed his intelligence skills by breaking up anti-colonial cells.

Determined to find out more about his later role in Northern Ireland, I appealed to the Information Tribunal, an independent court which adjudicates disputes like this between journalists and the authorities.

Two lawyers, Darragh Mackin from Phoenix Law and Omran Belhadi from Nexus Chambers, agreed to assist me without charge.

A hearing was due to go ahead early last year, but had to be cancelled at short notice because court staff lacked sufficient national security clearances. The coronavirus pandemic then made it impossible to reschedule the hearing until now.

While we will not receive a decision today, I can at last reveal certain documents the police have disclosed during my appeal, which give us a better picture of Morton — the man who wrote the secret report at the centre of this case.

‘Very recently retired’

It turned out Morton was no longer a serving MI5 officer, an assertion I had queried. The police had to sheepishly clarify that he had “very recently retired from MI5 when he compiled the report. He was, therefore, a retired rather than a serving MI5 officer.”

This admission, which directly contradicted earlier statements by the Information Commissioner, only came after the police had instructed a senior barrister to defend their case.

The police then produced several faded documents from deep in their archives in an attempt to clarify what had happened. One was a letter from the then head of MI5, Sir Michael Hanley, who said Morton had retired in the summer of 1972 — a year before writing the report.

Another document they gave me suggested Morton’s last role at MI5, as “director of [the] counter-subversion branch with special concern for Commonwealth territories”, ended even earlier, in 1971 — so his retirement was not that recent at all.

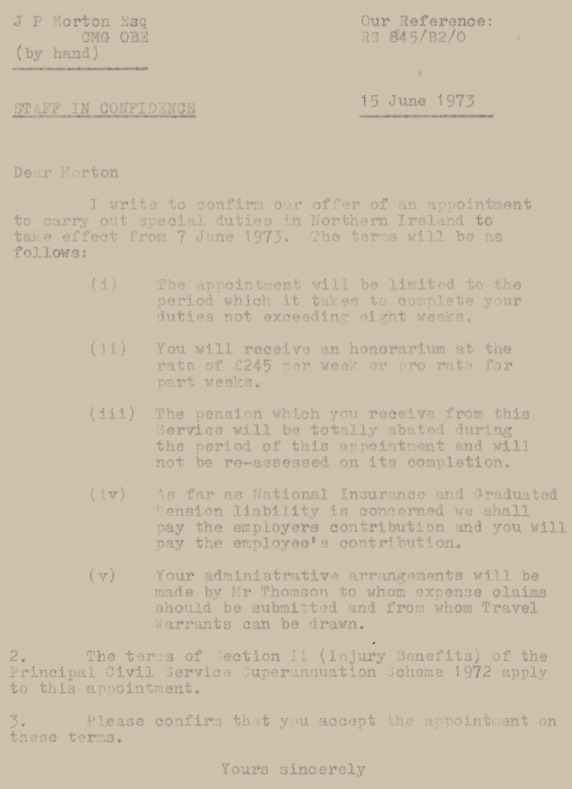

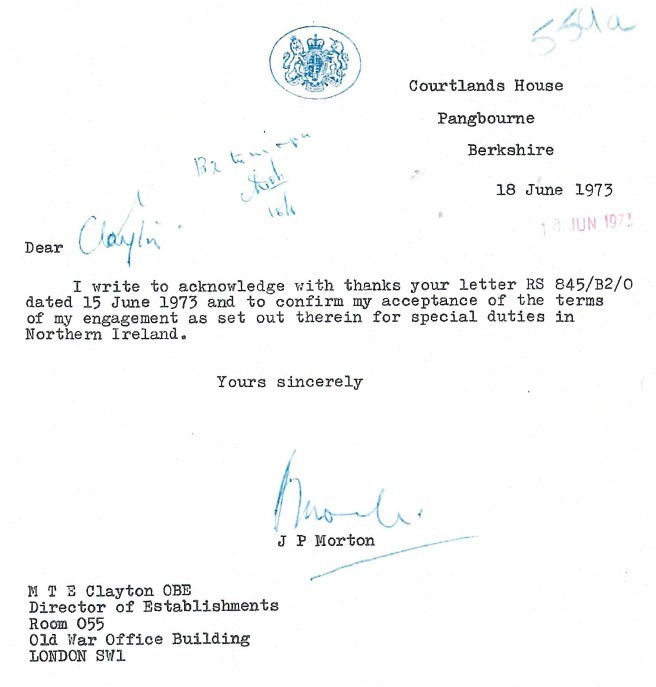

Although this admission appeared to seriously undermine the police’s position, they went on to claim that Morton was temporarily rehired by MI5 “to carry out special duties in Northern Ireland” for up to eight weeks and paid as much as £1,960 (worth around £24,000 today) to conduct the Special Branch review in 1973.

His contract was drawn up by staff in Whitehall’s Old War Office, a building 1,500m away from MI5’s headquarters at Leconfield House.

The police claimed these files showed the report was still exempt from the Freedom of Information Act, because it was supplied by someone who was “working directly on behalf of MI5 at all material times”.

My lawyers asked the police to provide a witness statement explaining the personnel and offices mentioned in this paperwork, as it was unclear if they were part of MI5, but we were told these records from nearly half a century ago were “self-explanatory”.

Some of the files are barely legible and there are probably very few people still alive who have the intimate knowledge required to explain the paper trail. Morton died in 1985. His memorial service at St Paul’s Cathedral in London was attended by Michael Hanley, who himself died 20 years ago.

MI5 inconsistency

The decision to disclose certain MI5 paperwork is also curious, as the police case rests on the claim that Morton’s report cannot be released solely because it came from MI5.

Why then am I allowed to see some MI5 documents but not the report itself?

For instance, the police gave me: a letter written by the head of MI5; Morton’s home address in Pangbourne, Berkshire; and a copy of his career history.

Morton’s CV shows he spent 41 years working for the British crown, with 17 of them as a policeman in India before he joined MI5 at the country’s partition in 1947.

Once in MI5, Morton undertook several lengthy secondments to the Colonial Office and the governor of the then British colony of Malaya, where he was director of intelligence. He also studied at the Imperial Defence College.

In sum, the majority of Morton’s career was not spent at MI5 and the advice he gave Northern Ireland’s police in 1973 would surely have been drawn from his experience with a variety of security organisations, not all of which are exempt from the Freedom of Information Act.

For instance, Morton’s early career is detailed in his memoirs, An Indian Episode, which he personally deposited at the British Library a few years before he died.

And in another case similar to mine, Northern Ireland’s police were willing to release material which they had initially argued could never see the light of day.

In 2018 a human rights group in Belfast, the Committee on the Administration of Justice, persuaded the police to disclose a lightly-redacted copy of a report about the Special Branch compiled in 1980 by Sir Patrick Walker.

Unlike Morton, Walker was a serving MI5 officer when he wrote his report and would go on to run the Security Service until 1992.

Walker’s report was released despite the damaging details it contained, such as the suggestion that arrests of terror suspects “must be cleared with Special Branch” in advance, to ensure they were not in fact state agents.

Or the advice that detectives “should not proceed immediately to a charge whenever an admission has been obtained” from suspects. Self-confessed criminals might, after all, be willing to work undercover for the British state and spy on their mates if it spared them jail time.

So we now have the bizarre situation where an MI5 officer’s report on Northern Ireland’s Special Branch from 1980 has been released but one written by a retired MI5 man from 1973 remains under wraps.

Yet Morton’s important career has rarely been easy for journalists and historians to understand.

He was brought out of retirement again in 1979 and dispatched to Sri Lanka, where he suggested that battle-hardened SAS troops help set up an army commando unit to deal with the Tamil independence movement. It was at that stage mostly a peaceful struggle but the country soon became engulfed in a full-scale civil war.

I only know the details of his trip from Ministry of Defence files buried at the National Archives in London. The Foreign Office, which arranged his visit, shredded their copies.