Two years ago, British soldiers were cooking on an army exercise in Kenya when things suddenly spiralled out of control. Sparks from their small stove ignited the grass at Lolldaiga, on the foothills of Mount Kenya.

This might have been a minor incident, had the area not been so dry. Unfortunately, these were “tinderbox” conditions, as Britain’s high commissioner Jane Marriott would readily admit. The grass went up in smoke. Trees exploded from the heat. Before long, what started as a cooking accident was a full blown forest fire.

At least 7,000 acres, an area larger than the 11 square mile London borough of Lambeth, was torched. Water turned black as smoke rained down on the nearest town, Nanyuki. “The roads were thrown into darkness,” environmental activist James Mwangi Macharia recalled. “You had to drive with your headlights on – in the middle of the day.”

At the centre of the inferno, headlights were not enough to stop accidents. As one truck carried volunteers to fight the fire, it collided with Lolldaiga ranger Linus Murangiri, crushing him to death. “If it was not for the fire, Linus would still be alive,” his widow Karen Gatwiri told me.

Sitting with her two small children in a dark tin shack, she confided: “Linus used to complain that anytime the British army visited Lolldaiga they were rowdy, causing explosions and lighting fires that the workers had to extinguish.”

Her husband had good reason to be worried. UK soldiers caused five smaller fires at other training camps in Kenya in the month before the Lolldaiga blaze of March 2021. Yet the military was still woefully unprepared for forest fires.

Obito Ntaiya, a keen footballer who comes from a Maasai community that neighbours Lolldaiga, was among those who scrambled to fight the fire. “We had nothing at all to cover our faces,” he explained. “The traditional method is to use a bush to beat the flames, but it can burn you.”

In the end, water dropped from helicopters was needed to stop the blaze, which lasted for several days.

Another volunteer fireman bounced along a dirt track by Lolldaiga’s perimeter before dismounting his motorbike to talk to me. “We were extremely scared that the fire, given the dry conditions, could spread to unimaginable levels,” he said. “Even towards the community lands.”

Damage limitation

The British army insists no communal land was damaged by the fire, which it claims only burnt the privately-owned Lolldaiga conservancy. Yet during a week I spent there in November, a very different story emerged.

“That fire carried highly hazardous smoke and that’s why you can see all these problems that have been narrated by the community,” Macharia lamented, standing in a circle of children at a local orphanage.

The environmental activist exclaimed: “There is more than what is being told. The problem is way bigger. The fire produced smoke that was toxic and is destroying the health of every human being living around this area.”

To prove his point, we had visited Mbogo-Ini, a primary school and refuge 10 miles west of Lolldaiga. It’s seen an influx of destitute children since the fire. Their parents lost crops or animals from the smoke, leaving them unable to feed their families.

Dozens of malnourished boys and girls wearing oversized red jumpers turned out to greet us. One poor child fainted from hunger while we were there. Many struggle with sickness brought on by the fire.

“I’ve been really affected”, Samuel Lokure complained while holding a long white cane. “My eyes, my nose, my whole breathing system. Before I was able to see. But for now I don’t really see well. My eyes are itching every day. I’m totally disabled.”

Class action

Samuel is among 5,563 Kenyans who filed compensation claims against the British army at the end of 2022. Together, they are demanding an eye-watering £1 billion worth of damages from the fire. That figure might seem hard to fathom until you see the scale of suffering surrounding Lolldaiga Hills.

As I travelled between farmsteads for mile after mile, villagers came out to greet me wearing T-shirts with the slogan ‘Justice for Lolldaiga’. The instigator of this class action is Macharia, whose little-known campaign group, the African Centre for Corrective and Preventive Action (ACCPA), had previously taken on the tobacco industry.

“Many thought I was crazy to launch civil litigation against a powerful military,” he admits. “But Kenya has many fine laws on paper – the challenge is getting the courts to enforce them.” The ACCPA swiftly lodged a claim at Nanyuki’s environmental and land court, bussing in petitioners by the coach load.

There they were met by a wall of resistance from the British army’s slick city law firm, Dentons Hamilton Harrison and Mathews, who tried to claim the UK military had “sovereign immunity” from any litigation in Kenyan courts.

After almost a year of hearings, Justice Antonina Kossy Bor shot down this argument, ruling that Kenyan citizens had the right to take the British army to court in their own country. “I’m proud that we are the only organisation in Africa that melted the perceived sovereign immunity of the British army,” Macharia remarked, savouring his victory over the old colonial master. “This has allowed the community to seek damages.”

But there was a catch. Under a military treaty between the UK and Kenya signed in 2016, compensation claims would have to be scrutinised by an inter-governmental liaison committee (IGLC). Half of its members are British officials. It is co-chaired by Brigadier Ronnie Westerman, the defence attaché at the UK high commission who had initially pushed for sovereign immunity.

“Half of its members are British officials”

Not only is it unclear if the claims will be handled fairly. For some, justice delayed has meant justice denied. Macharia estimates around 50 elderly claimants passed away in the interim, with some suffering from health conditions blamed on the fire.

Five of the lead claimants had to spend a night in the cells at Nanyuki police station, after someone falsely alleged they were extorting money to pay for court costs. “It was not comfortable,” John Kiunjuri, chairman of Justice for Lolldaiga campaign, remembered.

“We slept in a cold place without food or even being let out to go to the toilet. They had to bring a bucket, so that we could put our body waste in.” Kiunjuri and his aged companions were released on bail the next morning and the charges withdrawn.

When the community was eventually ready to file their thousands of compensation claims, the IGLC only provided an email address for them to submit the claims. The inbox quickly filled up with the volume of attachments and emails began to bounce.

In the end, after several complaints to the UK embassy, Brigadier Westerman gave permission for claims to be hand delivered on a hard drive to the British lawyer’s office in Nairobi on 30 December. By that point, any veneer of IGLC impartiality had worn off.

Ghosts of empire

For now, the Lolldaiga community can only wait to see the outcome of their claims. Yet the process of getting this far has been formative in itself. When I watched their first court hearings over a video link from London, the community’s advocates included a law student, Kelvin Kubai.

As the case progressed, Kubai qualified as a lawyer and joined forces with Macharia at the ACCPA to register as many fire victims as possible. They set up temporary offices across two sites in Nanyuki town, the second premises on the airy floor of an empty school block.

When I visited the town last year, dozens of volunteers crowded around desks, laptops and scanners, painstakingly digitising the reams of paperwork. Detailed maps of British army training grounds in Kenya hung from one wall.

Even those unaffected by the fire felt compelled to help out. Esther Njoki, whose aunt Agnes Wanjiru was murdered by a British soldier in 2012, sat busily at one scanner and accompanied the team on field trips to inspect the fire damage.

Emerging from the ashes, this case has become a flashpoint for more than a century of grievances against Britain’s presence in Kenya. Kubai is no ordinary lawyer. His grandfather was Musa Mwariama – the highest-ranking Mau Mau member to evade capture by British colonial forces during their war for independence in the 1950s.

“He was a Field Marshal with more than 2,000 soldiers in his main camp,” Kubai divulged. “He had other satellite camps strategically scattered across Mount Kenya forest.” The Mau Mau, properly called the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), sought to reclaim the ‘White Highlands’ – areas like Lolldaiga where the country’s most fertile soil had been seized by European settlers for farming and tea plantations.

“More than a century of grievances against Britain’s presence in Kenya”

According to journalist John Kamau, “an estimated 3,600 White settler families, constituting only one per cent of the population, occupied about 20 per cent of Kenya’s arable land while six million Africans were pushed to the so-called Native Reserves and ‘tribal lands’.”

To quell the Mau Mau uprising, the Royal Air Force dropped bombs weighing a total of six million pounds. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of people were held in detention camps, where torture and executions were routine. Men were castrated with pliers. It was only after the movement had been heavily suppressed that Britain agreed to hand control over to a more pliant political class.

“There was a frustration from the Mau Mau after the war,” Kubai commented, reflecting on Kenya’s journey since independence in 1963. “They realised colonialism was still there. The Mau Mau fought for restoration of land – but it was withheld by the political elite. Our first president, Jomo Kenyatta, pocketed much of it.”

The Kenya Land Alliance, a campaign group, estimates Kenyatta’s family are the largest landowners in the country, with half a million acres. Kubai’s grandfather was friends with Kenyatta, but gained little from that relationship.

“An act was passed where ordinary people had to buy the land, even though it was originally theirs before the white settlers came,” Kubai explained. “My grandfather had to pay a land trust loan. Those not able to pay the loan lost the land.”

Fortress conservation

At Lolldaiga, little changed. The settlers chose to remain and acquire Kenyan citizenship. It was a common tactic across Laikipia county, part of the White Highlands that forms Kenya’s bread basket.

In Laikipia’s main town, Nanyuki, the British military had run a rear base during the Mau Mau war. Afterwards, a more modern barracks was born – the British Army Training Unit Kenya (pronounced Batuk). It provided a reassuring presence both to old colonials and Kenya’s nascent authorities, who worried neighbouring states might try to capture their territory.

In time, settler families rebranded their ranches as wildlife conservancies. Imperial-style trophy hunting was out. Poachers turned gamekeepers. Kubai believes it was a cynical move to secure greater legitimacy for their estates – an image makeover for colonial-era land grabs (put simply, theft, to use Prince Harry’s description).

This is not to say that all wildlife resorts in Laikipia today are owned by the descendents of settlers. Some European farmers came to Kenya post-independence and defenders of the conservation industry claim African ownership and involvement is on the rise.

Yet 40% of land in Laikipia remains in the hands of just 48 entities, a stubbornly high statistic six decades after independence. Tensions sometimes boil over into ‘farm invasions’, where pastoralists squat their cattle inside the conservancies.

In extreme cases, large landowners have been attacked. When Italian-born aristocrat Kuki Gallmann was shot at her Laikipia home in 2017, a British army helicopter evacuated her to hospital. She survived, but others have not.

Most of the time though, the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) provides a formidable layer of security around the conservancies. This state agency has the power to shoot on sight any suspected ivory poachers.

British soldiers, including a military intelligence expert, have trained and advised KWS rangers since its inception. Much of its funding comes from international animal charities, which have pumped money into KWS to save elephants and rhinos.

“An image makeover for colonial-era land grabs”

As the profile of these endangered species grew, Kenya marketed itself as a safari destination, with white ranchers building luxury lodges on their conservancies to accommodate western tourists. Lolldaiga advertises their “sprawling old settler-style house” for $300 a night per person, complete with a swimming pool.

Campaign group Survival International has dubbed this high-security, luxury safari industry as ‘Fortress Conservation’. Kubai went further. “Conservation is a pure lie. It’s a front for fundraising from Europe.”

This description might be too crude, but there is certainly a lot of money to be made from it. I met some of the clientele when travelling between Nairobi and Nanyuki. Other than going by road, the main method of transport is Safarilink, a bespoke airline co-founded in 2004 by a British businessman.

Inside one of their single-propeller ‘caravan’ planes, I was surrounded by wealthy American holidaymakers. A sticker declaring HANDS OFF OUR ELEPHANTS decorated the fuselage. Before dropping me in Nanyuki, the jet touched down on a dirt landing strip as elephants sprinted away from the runway.

Our high speed touchdown seemed at odds with the plane’s slogan, but the other passengers were thrilled to arrive at their safari lodge for a trip of a lifetime, as they posed for selfies on instagram.

Lucrative business

This is clearly a lucrative business for those who own the conservancies, yet it has not been enough to sustain their lifestyles. Fortunately for them, another income stream has emerged from a surprising source: the British army. It pays handsomely to use these same nature reserves as military training areas.

Between 2010-16, the UK military gave £7m to around a dozen landowners in Laikipia, according to official accounts analysed by Declassified. An army spokesman said: “Landowners are compensated at the appropriate rate for the use of their land.” Lolldaiga received £1.2m from that pot. More recent data is unavailable.

In that period, the estate was owned by Robert Wells whose grandfather obtained the land during colonialism. Wells sold most of his family’s stake in Lolldaiga after the fire. Since then, around £5m worth of land and property has been purchased in rural England under his wife’s name.

Whatever the reason for moving to Britain, the timing of these sales has fuelled suspicion. “In the middle of an active case they transfer ownership,” Macharia noted. “Why did he do that? Someone is escaping responsibility. I’m astonished by that move. To this community he is a fugitive.”

The news is made more bitter by the fact that Karen Gatwiri, whose husband was crushed in the fire, received just £11,000 in compensation from the Wells family. He had worked for them at Lolldaiga since 2016, cleaning the swimming pool and welcoming guests.

Eleven grand might sound significant, but the cost of living in Kenya is higher than Westerners might think. When I visited his widow, she was living in an extremely poor township, running a kiosk that sold basic items to workers from the nearby (European owned) horticultural farm. “Life has been very hard. I don’t have enough money to pay the children’s school fees. Their father was covering that,” she explained.

“The children are asking me all the time if their father is coming home. Now I’m renting this house and some months I can’t afford it. My boys must go to university. I want them to have a career as doctors or lawyers.”

When told about the sale of Lolldaiga, Gatwiri commented bitterly: “It’s very bad. Robert Wells did a terrible thing at Lolldaiga, by letting the army train there. My husband’s death will always linger in my mind. It’s unforgettable.”

Declassified was not able to contact Wells for comment on this article. In response to a previous enquiry, his representative said Gatwiri’s family was paid compensation equivalent to 10 years salary.

Drought

When the fire first started at Lolldaiga, media attention focused on allegations that elephants had died in the blaze. One British soldier wrote on Snapchat: “Caused a fire, killed an elephant and feel terrible about it but hey-ho, when in Rome.” British officials strenuously denied that any such animals had died.

With the focus elsewhere, the death of Gatwiri’s husband was not made public until four months later. The delay is symptomatic of western concern when it comes to Kenya, where elephants are afforded greater sympathy than its human inhabitants.

For many rural Kenyans, elephants are regarded more as a threat than an endangered species. They can kill humans, destroy property and consume huge amounts of vegetation and water.

“Elephants are afforded greater sympathy than its human inhabitants”

This last issue is particularly acute, because Kenya is in the grip of a severe drought, induced by climate change. Parts of the north have not seen rain in two years. The drought is pushing pastoral communities further south into Laikipia as they search for grass on which to graze their cattle.

In this context, the fire at Lolldaiga was disastrous. On the front line was a Maasai settlement, Kimugandura. Before the fire, they paid Wells to graze their cattle on parts of the conservancy (giving him another income stream).

“We had an agreement with Lolldaiga to graze our animals there – 10,000 cows. Half have died from the fire,” a Maasai leader, Saituk Kaparo, commented as he showed me a burnt barn. “We have suffered a lot. This was a cattle shed but they never made it out of the fire alive.”

Another Maasai herder, Elijah Meshami, told me: “I’ve gone from having 300 to five cattles. They caught a disease from the smoke. The pastures we depend on are gone. We’re being forced to migrate because of the drought as well.” Some Maasai are learning to herd Somali camels, which consume less water than their cattle.

The community is also angry that medicinal plants were destroyed in the fire. Meshami reflected: “There’s a high rate of coughs among us. Some of us were even injured from fighting the fire. During that time we had lots of sick people around the community and wild animals were running away from the fire.”

Two vets confirmed the scale of animal deaths and injuries. “Unfortunately a lot of cows have lost their eyesight. They’ve gone blind from conjunctivitis and bovine blindness,” Reuben Maina said.

His colleague, Flavian Njuguna, added: “It’s massive, the amount of cattle who’ve died from the fire. During the incident, most died due to smoke inhalation. Approximately more than 30,000. Some sheep and goats also died from the smoke. The same number, about 30,000 too.”

Lantano Nabaala, the elected speaker at the county assembly in Laikipia, stressed the impact of this loss on the Maasai. “It is the animals that give the pastoralists pride. Animals define who a person is in society. The more cows you have, the more you are respected.

“So when you kill our animals, you’ve not only killed what I could sell for food. You’ve also killed me as a person,” the politician explained. “In our communities, if you have a big multi-coloured bull, you will be referred to at all times as the elder with the multi-coloured bull. So the bull kind of becomes synonymous with you.”

The elephant fence

In Maasai culture, Lolldaiga takes its name from daiga, which means a hill symbolising when rain is coming. Yet while I was there, the rain remarkably avoided its barren hills, as I watched clouds form across Laikipia. “It’s a desert mountain now,” Macharia lamented. “Think about the amount of carbon that was emitted.”

Obito Ntaiya, the footballer, fears Lolldaiga’s landscape has changed forever. “We used to predict the rainfall by Lolldaiga. It was so predictable,” he said. “Lolldaiga is totally bare now. I just pray that everything can go back to normal.”

The British army claims it has planted 3,900 saplings in Kenya and dropped over 10,000 ‘seed balls’ from aircraft, in an effort to help trees recover. But these will take time to grow. And for now, there is little left in Lolldaiga for the elephants to consume. In response, they marauder outside the conservancy searching for water and grass.

When I visited, the situation was particularly tense. British troops had just resumed training at Lolldaiga, before the compensation row was resolved. To make their exercises more realistic, soldiers detonated plastic explosives to simulate battlefield noise.

This had the added effect of spooking the elephants (like when my plane landed), giving them extra incentive to charge out from the conservancy. The only thing to stop them is a waist-high wire fence, which was not electrified when I touched it.

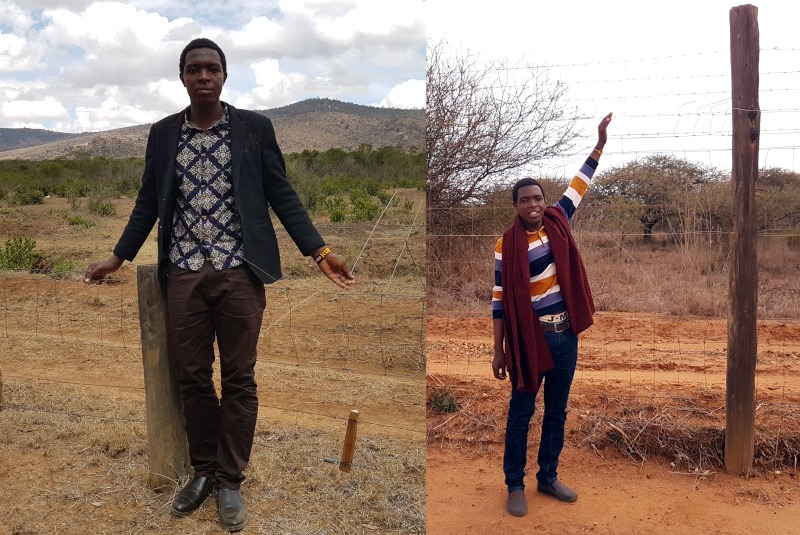

Once over the fence, the elephants ran amok among both Maasai and small-scale arable farmers. In a rustic clearing, I met half a dozen men from the self-help group, Musobek, which has spent almost a quarter century campaigning against elephant invasions from Lolldaiga.

James Kagunya, the group’s secretary, insisted: “Every time the army bombs there, the animals run this way. The noise means we cannot sleep. We want them to pay us for the trouble we have because of the explosions. The beneficiary is Robert Wells. He gets government support for tourism, plus the army training, and we get nothing.”

Kagunya continued: “It’s an insult for them to continue training before the court case is finished. Fencing is the first priority. They have to fix the fence. They should put it on their border. They cannot put a burden on the poorest community.”

The farmers produce paperwork stretching back to 1999 showing their efforts to raise this issue with Wells and KWS. In 2003, Kenya’s parliamentary Standing Committee on Human Rights concluded that the problem of “human-wildlife conflict in Daiga areas of Laikipia district is severe…The community, who have been the victims of the problem, have become impoverished and have not received any meaningful assistance”.

Twenty years later, no one has built a proper fence around the conservancy. “Who will inherit this responsibility?” Kagunya asked me, when I mentioned Lolldaiga had been sold. “We feel very much short changed by Robert Wells who ran away when he understood the genesis of the problem.

“Trespassing at Lolldaiga could be suicide. If you stray 200 metres, armed KWS officers will spot you,” he pointed out. “So why can’t they stop animals from escaping? The fence is only a metre high. Elephants can jump it. It’s not electrified. They don’t want to spend anything.”

After the latest exercise in Kenya, UK defence minister James Heappey admitted “elephants are able to move in and out of Lolldaiga, which is a privately owned ranch, at will.” He added that the British army “monitors wildlife in the immediate vicinity of training for safety reasons but does not track the movement of animals in and out of training areas.”

His relaxed attitude is particularly striking, given that a British soldier was killed by charging elephants in Malawi in 2019. A detailed investigation from that incident means the UK military is well aware of the threat elephants pose to humans. And yet they seem content to expose the farmers around Lolldaiga to rampages.

The men from Musobek are not the only ones making this complaint. Further along the perimeter is Nabulu, a group of Maasai women who run a soap factory. They took out a loan to build irrigated polytunnels in which they grow natural ingredients, from aloe vera to coconuts.

I received a flower-shaped bar of their soap, before being told the entire business is under threat. “After the fire, the elephants have abandoned the conservancy and are trying to live in the community lands,” Teresia Sarioyo said. “Our harvest has been devoured by the elephants.”

The main polytunnel had a 10 foot high tear the shape of an elephant down the middle. I treaded carefully to avoid their dung, or falling into potholes they created while digging up water pipes detected through their relentless sense of smell.

The Nabulu project effectively lay in ruins. “We’ve been making zero profit because of having to repair the fence so often,” Sarioyo said. “Everyone is asking why the army has been allowed to return.”

Spin doctor

On the other side of the wire, a British army press officer extolled the benefits of UK military training to hand picked Kenyan journalists. It is essential, he said, for troops to practise on this terrain before deployments to Afghanistan and Mali (wars Britain has either lost or is losing).

I was not invited to the media jamboree, which was conducted by a reservist, Major Adrian Weale. He was flown out from London for an 8-day PR push during the exercise at Lolldaiga. On his personal twitter account, Weale posted an image of an ostrich starter he enjoyed one night at a smart restaurant in Nanyuki.

Over on Batuk’s official twitter account, there’s an uptick in photo ops: soldiers delivering books to local schools or painting classrooms. Journalist Nicholas Komu counted a flurry of 11 community engagement activities over five weeks.

The surge in outreach appeared deliberate. UK ministers were pushing for Kenya to renew their military treaty with Britain, which expired in 2021 and has only been extended temporarily. Negotiations are stalled by concerns from the fire, and the failure to extradite a soldier suspected of murdering Njoki’s aunt.

Kubai fumed whenever the Twitter posts appeared. “Painting classrooms is not our priority,” he stressed. “Our children can still learn in unpainted walls. But what we cannot do is live in a polluted environment in an ecosystem with elephants charging around on the school run.”

And yet Kubai is not a firebrand. Like many of the people I met around Lolldaiga, their demands were surprisingly modest. An elephant proof fence. A complaints office in town where the public can file compensation claims. Fire engines on standby during military exercises. Separate zones for the army and wild animals.

Even the American class action culture sits uncomfortably. Yet they are forced by the IGLC to individualise each and every claim of harm. Macharia would rather the money went on funding specific projects, like building a new school for the orphans, instead of personal payouts.

After all, Kenyans have seen mixed results from earlier litigation. In 2013, 5,228 Mau Mau veterans were granted £20m from the British government in recognition of the abuse they suffered during colonial rule. Nearly a decade on, many are still waiting for the money to arrive.

In another tragic case, 1,274 nomadic herders who lost life and limb from bombs left behind by British troops received £5m in the 2000s. But with little experience of managing bank accounts, many were overwhelmed by the sudden influx of cash. Some now languish in poverty and struggle with alcoholism.

If the Lolldaiga community wins this battle with the British army, there may be many more to come. The ashes of an empire still smoulder, stubbornly refusing to go out.