La Línea de la Concepción looks like any other traditional southern Spanish town. Its houses, painted in soft pastel colours, spread out from the beach which runs down its side. Locals sit sipping double espressos at the ubiquitous cafes in the late afternoon sun.

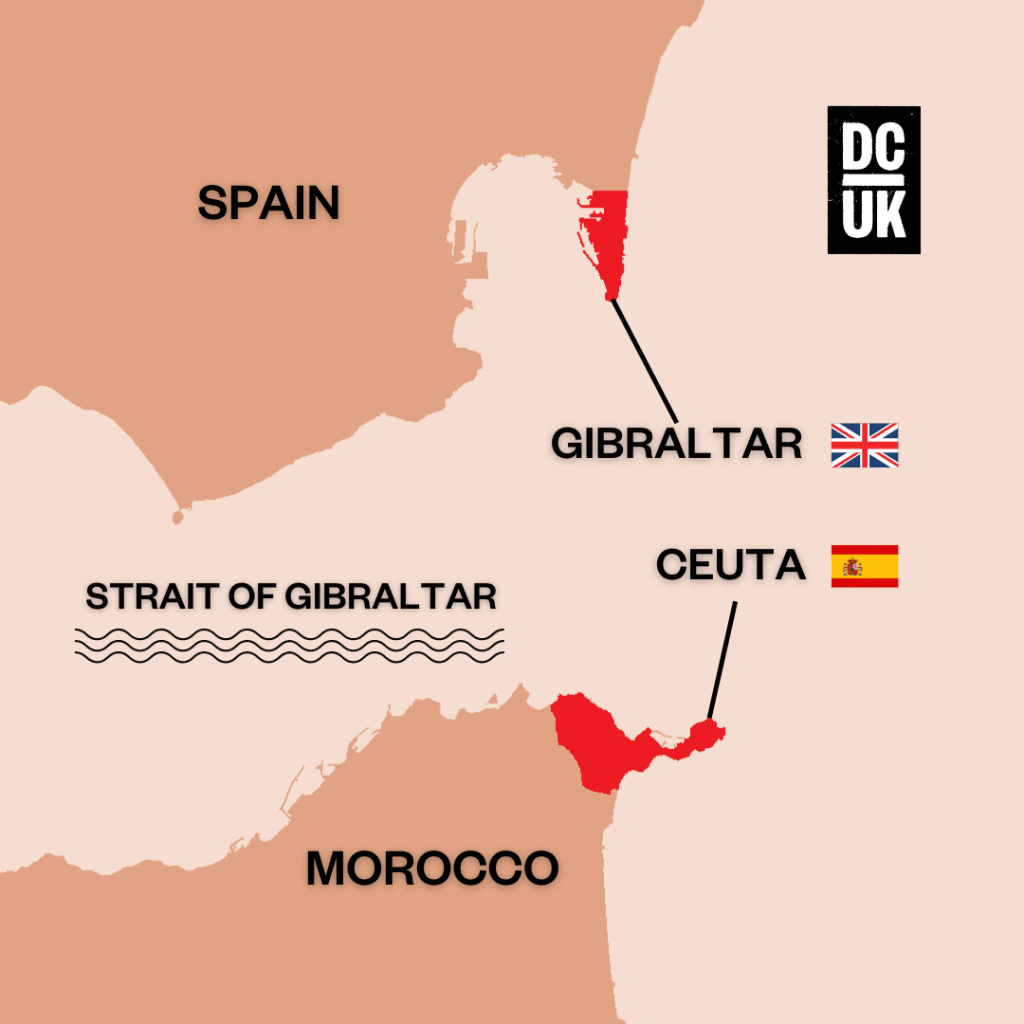

But this is the only border town in the province—and the border is with Britain. Next door is Gibraltar, the tiny territory which the UK has controlled since 1704.

Going from Gibraltar into La Línea does not feel like entering a new country. The border crossing is just a simple room and takes seconds. On the way out electronic machines read your passport, on the way back you flash it at a British guard.

But this may not last. The border, which has remained controversial through its existence, is at the centre of ongoing negotiations about Gibraltar’s status post-Brexit.

Known more commonly as La Línea, or The Line, it’s home to around 60,000 people and they like Gibraltar here. I talk to Elena, a 50 year old woman who was born and grew up in the town. “There is more work there than in Spain—and it pays better,” she tells me, adding that this is the majority feeling.

She works in the UK territory. “They have better legal regulations in Gibraltar which means they honour contracts there. In La Línea the contracts are more precarious and working conditions aren’t as good.”

Another local, Isabel, 51, has also lived her whole life in La Línea. “The truth is I’ve never had a problem with Gibraltar because it means there’s another, distinct economic regime which gives jobs to Spanish people. So I think that Gibraltar is looked upon very favourably by people here and it will continue like that into the future.”

She adds: “Most people think the same, because many of them work in Gibraltar, thousands of people that are working there, and their livelihood is dependent on it. They pay people pretty well. People I know working there are very happy. But of course there are always some people that don’t like it. There is some nationalism about it.”

Brexit

Things could soon get more complicated. Gibraltar was not included in the permanent post-Brexit deal which now governs the UK’s relations with the EU. Instead, it is now operating on ad hoc arrangements while negotiations continue.

Officially, these talks are between the UK and EU, but Gibraltar’s chief minister Fabian Picardo is involved as well. He will have to sell any deal to the Gibraltarians, but it will not be easy to keep everyone happy. The territory voted by 96% to stay part of the EU in the 2016 referendum.

Back in Gibraltar, Pablo, 28, is working inside EastGate freight service at the industrial zone next to the UK naval base. He has worked in Gibraltar for eight years, commuting from La Línea where he was born and grew up.

“It’s good for work here,” he tells me. “If you work in La Línea they rob you, it’s hardly any money. Here there are 18,000 Spanish people working. Thank God for Gibraltar because it gives me enough money to eat.”

He adds: “Many of my friends work here, it’s easy to get here, you just need an ID card. There’s no tension about the UK owning Gibraltar.”

Adrian Dano, 48, is a local guide in Gibraltar who has lived in the territory all his life and is intensely proud of being British. “The feeling at the moment is not much has changed because we’ve always experienced border problems with Spain for many years,” he tells me.

General Franco, then Spain’s dictator, closed the border completely in 1969, two years after a referendum in Gibraltar where 99% of the population voted to be British. The closure lasted until 1985.

“Over those 16 years, everything had to be important by shipments, there were shortages of everything,” says Dano. “We had to get our passport stamps from other parts of the world before we could go to Spain for a summer holiday.” He adds: “It created animosity. We don’t want to go back to that.”

Military and intelligence importance

At the southern tip of this tiny tip of the Iberian peninsula retained by Britain the waters are chock-a-block with ships entering and leaving the Mediterranean. Oil tankers, cargo ships, Royal Navy patrol boats, all jockey for space.

The queues are not a surprise. This is the only western gateway into the sea which stretches all the way to Syria four thousand kilometres to the east. In the distance, across the shimmering dark blue waters, the mountains of Morocco are viewable.

The Strait of Gibraltar is among the most strategic maritime choke points in the world—and one Britain has effectively controlled since it captured this territory in the early 18th century, long before the United States of America was even a country.

This most southerly point of the peninsula, where I’m standing, is named Punta de Europa, or Europe Point, a hotspot for tourists on the hunt for some of the continent’s most spectacular views.

Turning around from Morocco, in the other direction is the Rock of Gibraltar, the famous limestone promontory which rises magnificently into the skies. In front of that, in a nod to the region’s Islamic past, is the Ibrahim-al-Ibrahim Mosque, one of the largest in Europe.

Radomes

But just behind the mosque, there’s something that is not for tourist consumption. There, on the hill looking out over the Straits, three huge golf balls peer over the shrubbery.

Just the tops are visible but it’s enough to know what these are: surveillance radomes, the tell-tale sign of an intelligence facility, in this case, likely to involve UK spy agency GCHQ. This is Windmill Hill signal station, a location from which the British keep an eye on the ships passing through the Gibraltar Straits.

The Foreign Office, which oversees GCHQ and MI6, refuses to say if there are any intelligence facilities located in Gibraltar.

“It is the longstanding policy of successive British Governments that we do not comment on intelligence matters,” it recently told parliament when asked about possible intelligence bases on Gibraltar.

“The Foreign Office refuses to say if there are intelligence facilities on Gibraltar.”

Investigative journalist Duncan Campbell, who revealed the existence of GCHQ, says Britain’s largest intelligence agency has long had collection facilities on Gibraltar, and they formed part of the ECHELON global surveillance erected by the UK and its allies during the Cold War.

This is confirmed by Privacy International who say the UK territory has played a “critical collection [role] over the past 60 years” for GCHQ. In 2003, Sir Francis Richards, then head of GCHQ, went directly from the spy agency to being appointed the governor of Gibraltar.

Declassified recently revealed the key role the territory played for NATO spying operations at the height of the Cold War.

UK refusal

Gibraltar is just 2.6 square miles in size, smaller than Richmond Park in London, and you can walk its circumference in a couple of hours. It has been retained by Britain for over three centuries because of its strategic location and its role in its military system.

“The strategic value of Gibraltar stems from its dominating position at the entrance to the Mediterranean,” a formerly secret UK military report from 1972 notes. “It is conveniently placed as a base for sea and air operations in both the Eastern Atlantic and Western Mediterranean.”

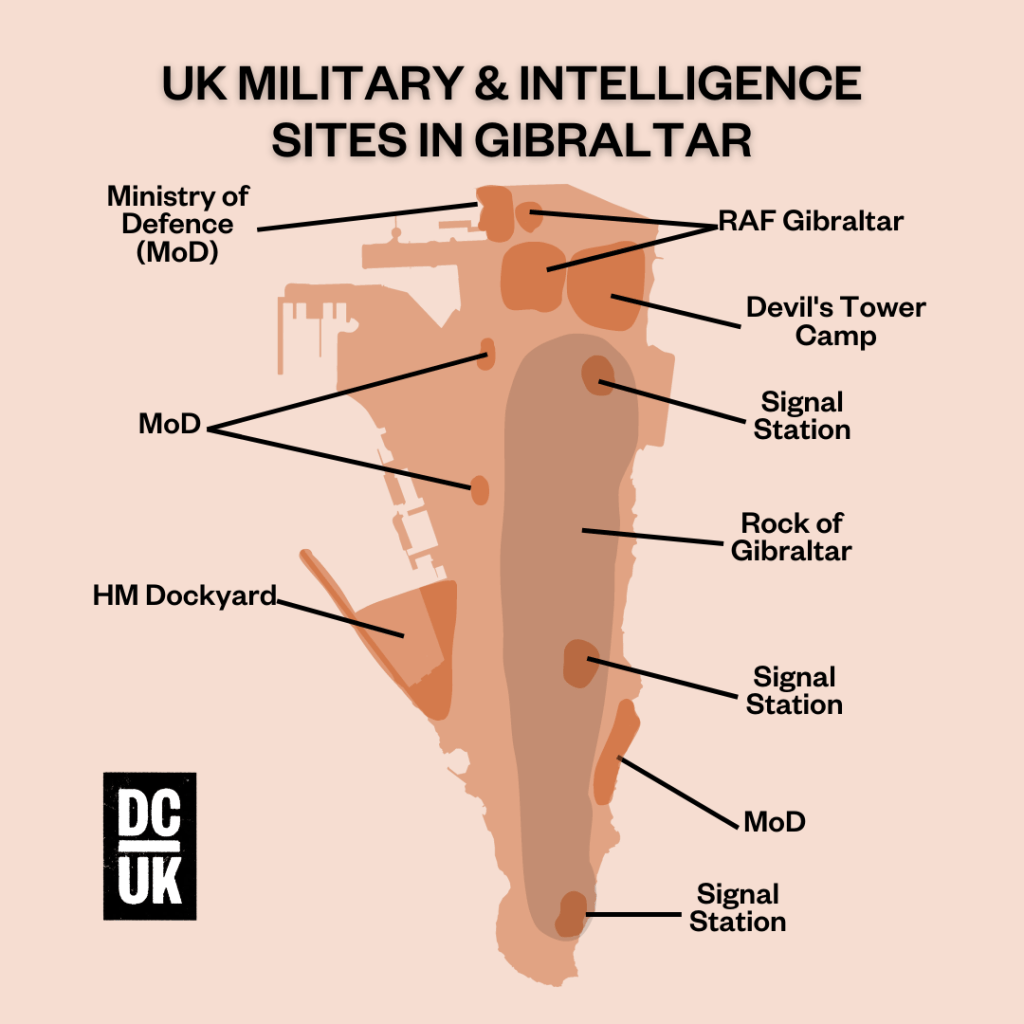

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) employs 952 personnel in Gibraltar, of which 528 are locally-employed civilians. The remainder are military. Gibraltar’s total population is around 33,000, which means 5% of all working age Gibraltarians are employed by the MoD.

All three services of the UK military are present in the territory. The largest unit, with 235 UK military personnel, is the Royal Gibraltar Regiment, an infantry force tasked with defending the territory from outside threats. It also performs a variety of ceremonial roles.

Some 28 personnel are deployed with the Navy’s Gibraltar Squadron, composed of two patrol boats, HMS Cutlass and HMS Dagger, which protect British and coalition vessels in the Strait. Another 16 UK military personnel are deployed at RAF Gibraltar, while 145 are assigned to British Forces Gibraltar headquarters, next door to the airport.

Gibraltar is routinely used by visiting Navy ships and RAF aircraft that temporarily deploy to conduct training. These visits total up to 14,000 personnel per year.

Militarised territory

But while it has divulged its personnel levels, the MoD refuses to provide details of all the sites it owns or operates on Gibraltar.

Asked recently in parliament for information, the department gave some information on army, navy and RAF deployments but also said that it “does not routinely comment on the equipment or capabilities held in any specific location.”

This is actually not routine practice—the MoD publishes the locations of its sites in Britain—and raises suspicions about the scale of its operations in Gibraltar.

To fill in the gaps, Declassified went all over the territory, including up the Rock itself, to map out the different military and intelligence locations. We found 11 different sites.

“The MoD refuses to provide details of all the sites it owns or operates on Gibraltar.”

The extent of this militarised territory could heighten tensions with Spain, which at the UN this month called for “the withdrawal of military bases and installations” the UK operates in Gibraltar.

Gerard Wood, head archivist at the National Archives of Gibraltar, told Declassified: “The realisation about its military importance dates back to 1704 when the British captured Gibraltar with the Anglo-Dutch fleet. I think they realised then the importance of the tactical location and its significance. Since then British forces have utilised Gibraltar quite significantly when the need has come.”

This has included important missions in World War 1 and 2, as well as the Falklands in 1982, and the First Gulf War in 1991.

“There’s always been a presence here, but obviously during the Cold War we would get a lot of ships, both English and American, coming over, and submarines as well,” Wood added. “I remember during my school days, I would look out of my bedroom window and the harbour would always have some sort of Royal Navy or US Navy presence.”

‘Prohibited area’

Continuing up from Europe Point around the east of the peninsula takes you up Europa Advance Road. Pavements are sporadic along the route, but the awesome views – now out east into the Alboran Sea – continue. On the left is the territory’s main crematorium perched perilously on a spit, then, on the right, a tourist cave complex.

Before long the road leads into a tunnel that juts deep into the Rock of Gibraltar itself. The cars follow the road into the rock, but another road leads straight on. This one, however, is guarded by an imposing 10-foot metal fence, topped with three layers of barbed wire. CCTV cameras peer down from both ends.

“This is a prohibited area under the Official Secrets Act,” it says in block capitals. “Unauthorised persons entering the area may be arrested and prosecuted.” Peering through the security, it’s impossible to know what is being guarded.

The tunnel itself is about half a mile long. When you emerge, Sandy Bay soon comes into view, Gibraltar’s most picturesque beach, regenerated with 50,000 tons of sand from the Western Sahara in 2014.

The highest point of the Rock is now visible, too. On it sits another series of golf ball radomes, this time peering out over Spain. This is the major surveillance facility at the former Rock Gun Battery at the summit of the Rock, which officially services RAF Gibraltar. It likely has other intelligence functions.

Later, I take a tour up the Rock and spotted another site of three radomes, but it is unclear what this site is.

On the way back into Main Street, the central strip of Gibraltar town, there is the site of the former Couvreporte Battery, established in 1761. The premises now sits behind a high metal fence with the obligatory three layers of barbed wire.

There are more signs this time. It’s a prohibited area under the Official Secrets Act again, but inside there is also an “explosive atmosphere”, it says. Anyone walking past is further warned that CCTV is in operation and the premises are alarmed. Inside it is hard, again, to gauge what is happening.

Further along on Main Street, the Governor’s residence, called the Covenant, is manned by a soldier from the Royal Gibraltar Regiment.

The hub

The two main operational military facilities on Gibraltar are RAF Gibraltar and Navy Dockyard.

The RAF base doubles as the civilian airport and you walk across the runway to get into Gibraltar from the airport. Barriers come down and traffic lights go red when a plane is due to land.

The southern part of the landing strip is reserved for a variety of military hangars, but there are no aircraft either permanently or temporarily stationed at RAF Gibraltar.

The airport is used regularly by UK military aircraft, 117 landing in Gibraltar 2022, with around 4,000 military passengers.

However, last year, just nine non-UK military aircraft landed in Gibraltar, eight from the US Air Force and one from Canada.

Next to the civilian airport is another RAF site. “MOD Property,” the sign reads. “This is a prohibited area under the Official Secrets Act.” On the other side of the road another MoD property sits behind gates. This time it’s unmarked.

Next to RAF Gibraltar is the Devil’s Tower Camp, the headquarters of British Forces Gibraltar and where many personnel are accommodated. Signs about the Official Secrets Act are again everywhere. Eastern Beach, another major tourist attraction, sits incongruously next door.

The most important part of Gibraltar for the British military is the naval base, which sits just down from the bustling main town.

The two patrol boats are permanently deployed there but the base also routinely hosts other UK or allied warships. In 2022, there were 79 UK ship visits, which amounts to about 6-7,000 naval personnel.

The patrol boats are active, responding to more than two boats per day on average last year. In 2022, they responded to 780 foreign government vessels in British territorial waters around Gibraltar. Of these incidents, 209 were classified as surface incursions.

Foreign troops

The MoD recently said there are four foreign military personnel currently deployed in Gibraltar, but refused to divulge which countries these troops come from.

“Allies and partners visit Gibraltar as required,” defence minister Jame Heappey said. “We do not provide specific detail on the countries from which these personnel originate.”

The department says there are no permanent NATO facilities in Gibraltar, but added: “NATO Allies are always welcome to request use of the UK’s military facilities in Gibraltar to support their operations.”

Declassified has revealed that Gibraltar secretly hosted a NATO-funded spy facility inside the Rock of Gibraltar and that the Alliance operated an underground maritime headquarters on the territory. It is not known if these facilities still operate.

Meanwhile, Spain’s position is that Gibraltar is a relic of colonialism and should be returned to it. The military role Gibraltar plays for the British has always been particularly controversial.

“Where appropriate to do so, the UK Ministry of Defence shares some information relating to military operations with Spanish authorities,” the department says. “This is in line with our usual practices for cooperating with Allies.”